Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

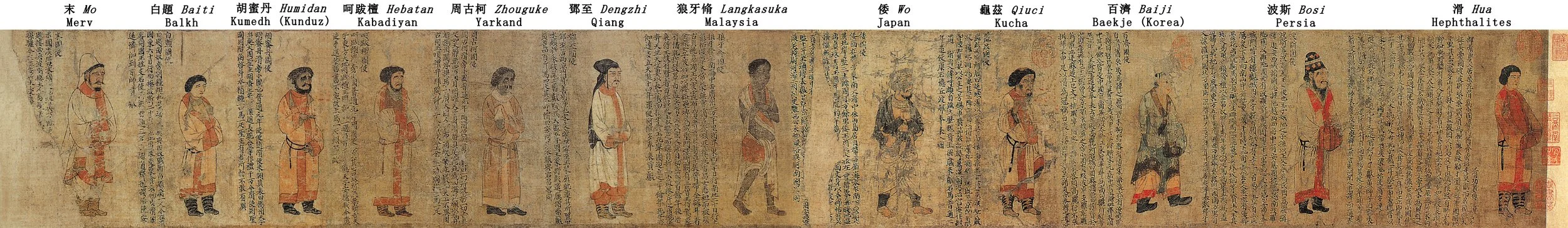

This episode talks about two projects that were started—but hardly finished—in the current reign. One of these was what Bentley describes as an “historiographical project” and the other was nothing less than the creation of the first permanent capital city: The city of Fujiwara-kyō

The Temmu-Jitō Historiographical Project

In 681, the sovereign gave orders to a group of Princes and high ministers to collect the various historical documents. There are many that believe this was the start of what would become the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, though given the differences, it seems like these works may have each leveraged some part of the effort, but may have been later works that put the historical details this effort gathered into context.

The group putting everything together included:

Royal Prince Kawashima - Second eldest son of Naka no Ōe (Tenji Tennō). He wouldn’t see the project through, either—or at least not the

Royal Prince Osakabe - Non-inheriting son of Ōama. He would also be involved with the Taihō Ritsuryō

Princes Hirose, Takeda, Kuwada, and Mino - Four non-royal princes, meaning that they were considered descendants of some prior sovereign, but their parents were not sovereigns, themselves. Unfortunately, these all appear to be locative titles, meaning they are names that come from locations that are passed to different individuals, making it difficult to determine who is who without more information. Still, it is key that they are outside of the ministerial class, and given some deference as being part of the extended royal family.

Kamitsukenu (Kōzuke) no Kimi no Michiji (Lower Daikin Rank) - The only one on the list with the “Kimi” kabane and the highest ranked official at Lower Daikin. In previous portions of the Chronicles, one would assume that that “Kimi” meant that they were the lords of Kōzuke, and the family seems to have had influence in the region. Unfortunately, they would pass away later the same year that they started the project.

Imbe no Muraji no Kobito (Middle Shōkin Rank) - A longtime supporter of the sovereign, he had joined the Yoshino side and defended Asuka, removing the planks from the bridges and building barricades to help defend from the Ōmi court. His kabane would later go from Muraji to Sukune under the new system.

Adzumi no Muraji no Inashiki (Lower Shōkin Rank) - Inashiki was a minister under the old Ōmi court, but not mentioned as directly fighting against Ōama, and would be among those pardoned by him. There must not have been too much distrust as he was clearly trusted with this task.

Naniwa no Muraji no Ōgata (no rank mentioned) - This individual is something of a mystery as no rank at all is mentioned and there seems to be no further mention of them in the Chronicles. We know that he was of the Naniwa family, which were previously the Naniwa no Kishi before they were given the status of Muraji. My assumption is that he was Lower Shōkin rank and they were just not restating it in the list.

Nakatomi no Muraji no Ōshima (Upper Daisen Rank) - Though a member of the powerful Nakatomi family, Ōshima’s position appears to have been that of scribe, helping to keep a record of what happened. This seemed to be the start of quite the career for Ōshima. He was a member of the Nakatomi house, but would later be listed as Fujiwara no Ōshima, from about 685 to 690. It is unclear if he took this name, or it was given to him—there is a bit of confusion around the name “Fujiwara” and which members of the Nakatomi clan would use it. This is something we should address at a later point in the story.

Heguri no Omi no Kobito (Lower Daisen Rank) - Another member of a prestigious family, but we don’t have much more to go on. Kobito itself is a fairly common given name in the Chronicles.

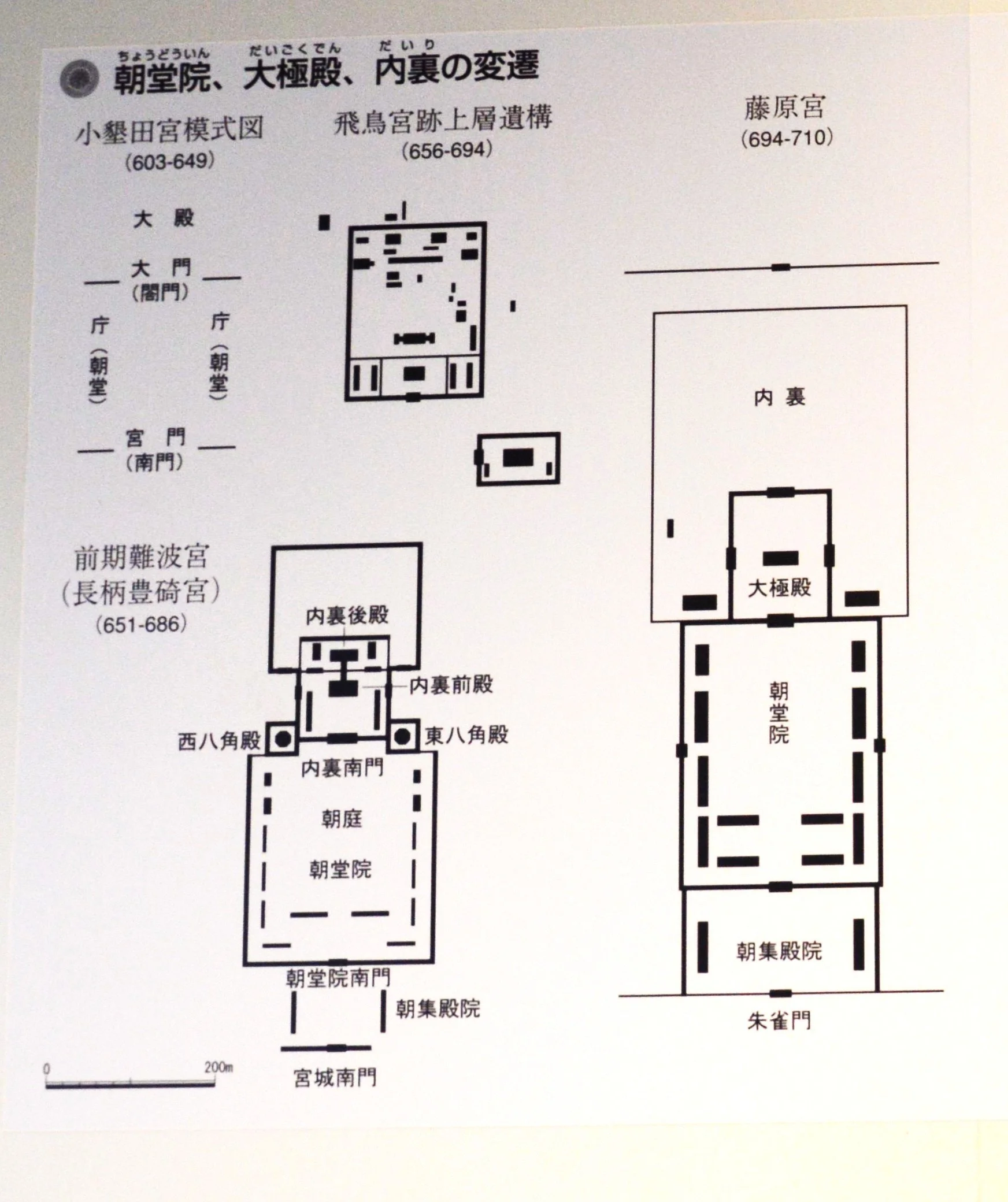

The Fujiwara Capital

We are going to discuss this more when we get into the next reign and they are actually occupying it, but the Fujiwara capital is the first time we’ve seen the state attempt to build an entire city. Previously we’ve seen “capitals” built, but it is mostly the palace, and we don’t necessarily see the larger infrastructure that was built around it. It may be that outside of the sovereign’s palace compound it was considered to be on the various ministerial families to figure out their own residences and lodging. However, in this instance it was full on large scale roads and blocks that were then divvied out amongst the ministerial families.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is Episode 143: Temmu’s Monumental Projects

Ohoama sat astride his horse and looked out at the land in front of him. He could still see the image of the rice fields, now long fallow, spreading out on the plain. To the north, east, and west, he could see the mountains that would frame his vision. As his ministers started to rattle off information about the next steps of the plan, Ohoama began to smile. He thought of the reports his embassies to the Great Tang had brought back, about the great walled cities of the continent. In his mind’s eye, Ohoama envisioned something similar, rising up on the plain in front of him.

There would be an earth and stone wall, surrounding the great city. The gates would be grand, much like the temples, but on an even greater scale. Houses would be packed in tight, each within their own walled compounds. In the center painted red and white, with green accents, would be a palace to rival any other structure in the archipelago. The people would stream in, and the city would be bustling with traffic.

This was a new center, from which the power of Yamato would be projected across the islands and even to the continent.

Greetings everyone, and welcome back. This episode we are still focused on the reign of Ohoama, aka Temmu Tennou, between the years 672 and 686.

Last episode we talked about the Four Great Temples—or the Four National Temples. Much of this episode was focused on the rise and spread of Buddhism as we see in the building of these national temples, but also on the changes that occurred as the relationship between Buddhism and the State evolved. This was part of Ohoama’s work to build up the State into something beyond what it had been in the past—or perhaps into something comparable to what they believed it to have been in the past. After all, based on the size of the tomb mounds in the kofun period, it does seem that there was a peak of prosperity in the 5th century, around the time of Wakatakeru, aka Yuryaku Tennou, and then a decline, to the point that the lineage from Wohodo, aka Keitai Tennou, seemed to have come in during a time when they were rebuilding Yamato power and authority.

This episode we are going to talk about two projects that Ohoama kicked off during his reign. He wouldn’t see the completion of either one, since both took multiple decades to complete, but both focused on linking the past and the future.

The first we’ll talk about is a new attempt to gather historical documents and records—the last time that was done was in the time of Kashikiya Hime, over 50 years ago. That was during the height of Soga power. Since then a lot had changed, and presumably there were even more stories and records that had been written down. Plus the tide had changed. So they needed to update—and maybe even correct—the historical record. But beyond that, there was a greater goal: Ohoama and his court also needed to make sure that the past was something that they wanted to go back to, among other things.

The other thing we are going to discuss is the start of a project to build a brand new capital city. And when we talk a bout city, we really mean a city. This was a massive undertaking, likely unlike anything that we’ve seen so far. Sure, there had been monumental building projects, but this was something that was going to take a lot more work - how much more monumental could you get than a new city? And it would create a physical environment that would be the embodiment of the new centralization of power and authority, and the new state that Ohoama was building, with his administration—and Yamato—at the center.

Let’s start with the big ones. First and foremost, we have the entry from the 17th day of the 3rd month of the 681. Ohoama gave a decree from the Daigokuden to commit to writing a Chronicle of the sovereigns and various matters of high antiquity. Bentley translates this as saying that they were to record and confirm the Teiki, which Aston translated as the Chronicle of the Sovereigns, and various accounts of ancient times. This task was given out to a slew of individuals, including the Royal Princes Kawashima and Osakabe; the Princes Hirose, Takeda, Kuwada, and Mino; as well as Kamitsukenu no Kimi no Michichi, Imbe no Muraji no Kobito, Adzumi no Muraji no Inashiki, Naniwa no Muraji no Ohogata, Nakatomi no Muraji no Ohoshima, and Heguri no Omi no Kobito. Ohoshima and Kobito were specifically chosen as the scribes for this effort.

We aren’t told what work was started at this time. Aston, in his translation of the Nihon Shoki, assumes that this is the start of the Kojiki. Bentley notes that this is the first in a variety of records about gathering the various records, including gathering records from the various families, and eventually even records from the various provinces. And I think we can see why. Legitimizing a new state and a new way of doing things often means ensuring that you have control of the narrative. Today, that often means doing what you can to control media and the stories that are in the national consciousness. In Ohoama’s day, I’d argue that narrative was more about the various written sources, and how they were presented. After all, many of the rituals and evidence that we are looking at would rely on the past to understand the present. The various family records would not only tell of how those families came to be, but would have important information about what else was going on, and how that was presented could determine whether something was going to be seen as auspicious, or otherwise. Even without getting rid of those records, it would be important to have the official, State narrative conform to the Truth that the state was attempting to implement.

Ultimately, there is no way to know, exactly, how everything happened. If the Nihon Shoki had a preface, it has been lost. The Kojiki, for its part, does have a preface, and it points to an origin in the reign of Ohoama—known as the sovereign of Kiyomihara. In there we are told that the sovereign had a complaint—that the Teiki and Honji, that is the chronicles of the sovereigns and the various other stories and legends, that had been handed down by various houses had come to differ from the truth. They said they had many falsehoods, which likely meant that they just didn’t match the Truth that the State was trying to push. Thus they wanted to create a so-called “true” version to pass down.

This task was given to 28 year old Hieda no Are. It says they were intelligent and had an incredible memory. They studied all of the sources, and the work continued beyond the reign of Ohoama. Later, in 711 CE, during the reign of Abe, aka Genmei Tennou, Oho no Yasumaro was given the task of writing down everything that Hieda no Are had learned.

The astute amongst you may have noticed that this mentions none of the individuals mentioned in the Nihon Shoki. Nor does the Nihon Shoki mention anything about Hieda no Are. So was this a separate effort, or all part of the same thing? Was Are using the materials collected by the project?

As you may recall, we left the Kojiki behind some time ago, since it formally ends with the reign of Kashikiya hime, aka Suiko Tennou, but realistically it ended with Wohodo, aka Keitai Tennou—after that point there are just lists of the various heirs. As such, there is some speculation that this was originally built off of earlier histories, perhaps arranged during the Soga era.

The general explanation for all of this is that Hieda no Are memorized the poems and stories, and then Yasumaro wrote them down. Furthermore, though the language in the Kojiki does not express a particular gender, in the Edo period there was a theory that Hieda no Are was a woman, which is still a popular theory.

Compare all of that to the Nihon Shoki. Where the Kojiki was often light on details and ends with Suiko Tennou, the Nihon Shoki often includes different sources, specifically mentions some of them by name, and continues up through the year 697. Furthermore, textual analysis of the Nihon Shoki suggests that it was a team effort, with multiple Chroniclers, and likely multiple teams of Chroniclers. I have to admit, that sounds a lot more like the kind of thing that Ohoama was kicking off.

We have an entry in the Shoku Nihongi, the work that follows the Nihon Shoki, that suggests 720 for the finished compilation of the Nihon Shoki. So did it take from 681 to 720 to put together? That is a really long project, with what were probably several generations of individuals working on it.

Or should this be read in a broader sense? Was this a historiographical project, as Bentley calls it, but one that did not, immediately, know the form it would take? It isn’t the first such project—we have histories of the royal lineage and other stories that were compiled previously—much of that attributed to Shotoku Taishi, but likely part of an earlier attempt by the court. In fact, given that the Kojiki and Sendai Hongi both functionally end around the time of Kashikiya hime, that is probably because the official histories covered those periods. Obviously, though, a lot had happened, and some of what was written might not fit the current narrative. And so we see a project to gather and compile various sources. While this project likely culminated in the projects of the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki, I doubt that either work was necessarily part of the original vision. Rather, it looks like the original vision was to collect what they could and then figure things out.

It would have been after they started pulling the accounts together, reading them, and noticing the discrepancies that they would have needed to then edit them in such a way that they could tell a cohesive story. That there are two separate compilations is definitely interesting. I do suspect that Oho no Yasumaro was working from the efforts of Hieda no Are, either writing down something that had been largely captured in memory or perhaps finishing a project that Are had never completed. The Nihon Shoki feels like it was a different set of teams, working together, but likely drawing from many of the same sources.

And as to why we don’t have the earlier sources? I once heard it said that for books to be forgotten they didn’t need to be banned—they just needed to fall out of circulation and no longer be copied anymore. As new, presumably more detailed, works arose, it makes sense that older sources would not also be copied, as that information was presumably in the updated texts, and any information that wasn’t brought over had been deemed counterfactual. Even the Nihon Shoki risked falling into oblivion; the smaller and more digestible Kojiki was often more sought after. The Kojiki generally presents a single story, and often uses characters phonetically, demonstrating how to read names and places. And it just has a more story-like narrative to it. The Nihon Shoki, comparatively, is dense, written in an old form of kanbun, often relying more on kanbun than on phonetic interpretations. It was modeled on continental works, but as such it was never going to be as easy to read. And so for a long time the Kojiki seems to have held pride of place for all but the most ardent scholars of history.

Either way, I think that it is still fair to say that the record of 681 was key to the fact that we have this history, today, even if there was no way for Ohoama, at the time, to know just what form it would take.

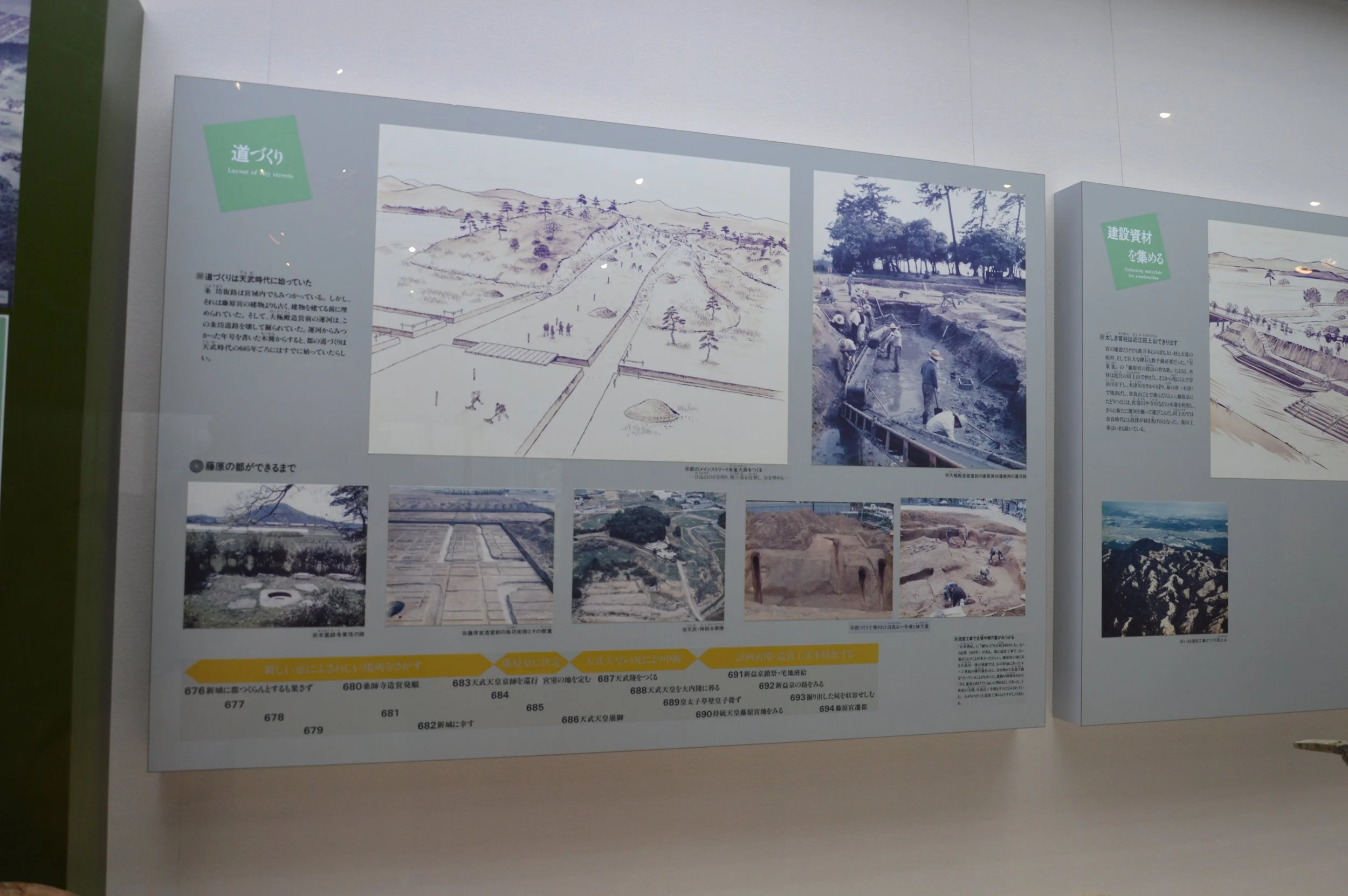

Another ambitious project that got started under Ohoama was the development of a new and permanent capital city.

Up to this point we’ve talked about the various capitals of Yamato, but really it was more that we were talking about the palace compounds where the sovereign lived. From the Makimuku Palace, where either Mimaki Iribiko or possibly even Himiko herself once held sway, to the latest palace, that of Kiyomihara, the sovereigns of Yamato were known by their palaces. This is, in part, because for the longest time each successive sovereign would build a new palace after the previous sovereign passed away. There are various reasons why this may have been the case, often connected to insular concepts of spiritual pollution brought on by the death of an individual, but also the practical consideration that the buildings, from what we can tell, were largely made of untreated wood. That made them easier to erect, but also made them vulnerable to the elements, over time, and is probably one of the reasons that certain shrines, like the Shrine at Ise, similarly reconstitute themselves every 20 years or so.

Furthermore, we talk about palaces, but we don’t really talk about cities. There were certainly large settlements—even going back to the Wei chronicles we see the mention of some 70 thousand households in the area of Yamateg. It is likely that the Nara basin was filled with cultivated fields and many households. Princes and noble households had their own compounds—remember that both Soga no Umako and Prince Umayado had compounds large enough that they could build temples on the compounds and have enough left over for their own palatial residences, as well. However, these compounds were usually distributed in various areas, where those individuals presumably held some level of local control.

It is unclear to me how exactly the early court functioned as far as housing individuals, and how often the court was “in session”, as it were, with the noble houses. Presumably they had local accommodations and weren’t constantly traveling back and forth to the palace all the time. We know that some houses sent individuals, men and women, to be palace attendants, even though they lived some distance away. This was also likely a constraint on the Yamato court’s influence in the early days.

We do see the sovereign traveling, and various “temporary” palaces being provided. I highly doubt that these were all built on the spot, and were likely conversions of existing residences, and similar lodging may have been available for elites when they traveled, though perhaps without such pomp and circumstance.

What we don’t really see in all of this, are anything resembling cities. Now, the term “city” doesn’t exactly have a single definition, but as I’m using it, I would note that we don’t see large, permanent settlements of significant size that demonstrate the kind of larger civil planning that we would expect of such a settlement. We certainly don’t have cities in the way of the large settlements along the Yangzi and Yellow rivers.

We talked some time back about the evolution of capital city layouts on the continent. We mentioned that the early theoretical plan for a capital city was based on a square plan, itself divided into 9 square districts, with the central district constituting the palace. This design works great on paper, but not so much in practice, especially with other considerations, such as the north-south orientation of most royal buildings. And then there are geographic considerations. In a place like Luoyang, this square concept was interrupted by the river and local topography. Meanwhile, in Chang’an, they were able to attain a much more regular rectangular appearance. Here, the court and the palace were placed in the center of the northernmost wall. As such, most of the city was laid out to the south of the palace.

In each case, however, these were large, planned cities with a grid of streets that defined the neighborhoods. On each block were various private compounds, as well as the defined markets, temples, et cetera.

The first possible attempt at anything like this may have been with the Toyosaki palace, in Naniwa. There is some consideration that, given the size of the palace, there may have been streets and avenues that were built alongside it, with the intention of having a similar city layout. If so, it isn’t at all clear that it was ever implemented, and any evidence may have been destroyed by later construction on the site. Then we have the Ohotsu palace, but that doesn’t seem to be at the same scale as the Toyosaki palace—though it is possible that, again, we are missing some key evidence. Nonetheless, the records don’t really give us anything to suggest that these were large cities rather than just palaces.

There is also the timeline. While both the Toyosaki palace and the Ohotsu palace took years to build, they did not take the time and amount of manpower that would be needed to create a true capital city. We can judge this based on what it took to build the new capital at Nihiki.

This project gets kicked off in the 11th month of 676. We are told that there was an intent to make the capital at Nihiki, so all of the rice-fields and gardens within the precincts, public and private property alike, were left fallow and became totally overgrown.

This likely took some time. The next time we see Nihiki is in the 3rd month of 682, when Prince Mino, a minister of the Household Department, and others, went there to examine the grounds. At that point they apparently made the final decision to build the capital there. Ohoama came out to visit later that same month.

However, a year later, in the 12th month of 683, we are told that there was a decree for there to be multiple capitals and palaces in multiple sites, and they were going to make the Capital at Naniwa one of those places. And so public functionaries were to go figure out places for houses. So it wasn’t just that they wanted to build one new, grand capital. It sounds like they were planning to build two or three, so not just the one at Nihiki. This is also where I have to wonder if the Toyosaki Palace was still being used as an administrative center, at the very least. Or was it repurposed, as we saw that the Asuka palaces had been when the court moved to Ohotsu?

This is further emphasized a few months later, when Prince Hirose and Ohotomo Yasumaro, at the head of a group of clerks, officials, artisans, and yin yang diviners were sent around the Home Provinces to try and divine sites suitable for a capital. In addition, Prince Mino, Uneme no Oni no Tsukura, and others were sent to Shinano to see about setting up a capital there as well. Perhaps this was inspired by the relationship between the two Tang capitals of Chang’an and Luoyang. Or perhaps it was so that if one didn’t work out another one might.

Regardless, Nihiki seemed to be the primary target for this project, and in the third lunar month of 684 Ohoama visited the now barren grounds and decided on a place for the new palace. A month later, Prince Mino and others returned with a map of Shinano, but there is no indication of where they might want to build another capital.

After that, we don’t hear anything more of Shinano or of a site in the Home Provinces. We do hear one more thing about Naniwa, which we mentioned a couple of episodes back, and that is that in 686 there was a fire that burned down the palace at Naniwa, after which they seem to have abandoned that as a palace site. And so we are left with the area of Nihiki.

This project would take until the very end of 694 before it was ready. In total, we are looking at a total of about 18 years—almost two decades, to build a new capital. Some of this may have been the time spent researching other sites, but there also would have been significant time taken to clear and level. This wasn’t just fields—based on what we know, they were even taking down old kofun; we are later told about how they had to bury the bodies that were uncovered. There was also probably a pause of some kind during the mourning period when Ohoama passed away. And on top of it, this really was a big project. It wasn’t just building the palace, it was the roads, the infrastructure, and then all of the other construction—the city gates, the various private compounds, and more. One can only imagine how much was being invested, especially if they were also looking at other sites and preparing them at the same time. I suspect that they eventually abandoned the other sites when they realized just how big a project it really was that they were undertaking.

Today we know that capital as Fujiwara-kyo, based on the name of the royal palace that was built there, and remarkably, we know where it was. Excavations have revealed the site of the palace, and have given us an idea of the extent of the city: It was designed as a square, roughly 5.3 kilometers, or 10 ri, on each side. The square itself was interrupted by various terrain features, including the three holy mountains. Based on archaeological evidence, the street grid was the first thing they laid out, and from what we can tell they were using the ideal Confucian layout as first dictated in the Zhouli, or Rites of Zhou. This meant a square grid, with the palace in the center.

Indeed, the palace was centered, due south of Mt. Miminashi, and you can still go and see the palace site, today. When they went to build the palace, they actually had to effectively erase, or bury, the roads they had laid out. They did the same thing for Yakushi-ji, or Yakushi-temple, when they built it as part of the city; one of the reasons we know it had to have been built after the roads were laid out.

We will definitely talk about this more when we get to that point of the Chronicles, but for now, know that the Fujiwara palace itself, based on excavations of the site, was massive. The city itself would surpass both Heijo-kyo, at Nara, and Heian-kyo, in modern Kyoto. And the palace was like the Toyosaki Naniwa palace on steroids. It included all of the formal features of the Toyosaki Palace for running the government, but then enclosed that all in a larger compound with various buildings surrounding the court itself. Overall, the entire site is massive. This was meant as a capital to last for the ages.

And yet, we have evidence that it was never completed. For one thing, there is no evidence that a wall was ever erected around it—perhaps there was just no need, as relations with the mainland had calmed down, greatly. But there is also evidence that parts of the palace, even, were not finished at the time that they abandoned it. Fujiwara-kyo would only be occupied for about 16 years before a new capital was built—Heijo-kyo, in Nara. There are various reasons as to why they abandoned what was clearly meant to be the first permanent capital city, and even with the move to a new city in Nara it would be clear that it was going to take the court a bit of time before they were ready to permanently settle down—at least a century or so.

Based on all the evidence we have, and assuming this was the site of the eventual capital, Nihiki was the area of modern Kashihara just north of Asuka, between—and around—the mountains of Unebi, Miminashi, and Kagu. If these mountains are familiar, they popped up several times much earlier in the Chronicles--Mostly in the Age of the Gods and in the reign of the mythical Iware-biko, aka Jimmu Tennou. Yet these three mountains help to set out the boundaries of the capital city that was being built at this time.

There is definitely some consideration that they were emphasized in the early parts of the Chronicles—the mythical sections, which were bolstering the story of Amaterasu and the Heavenly Grandchild, setting up the founding myths for the dynasty. Even though the Chronicles were not completed until well after the court had moved out, the Fujiwara capital is the climax of the Nihon Shoki, which ends in 697, three years into life at the new palace. And so we can assume that much of the early, critical editing of the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki were done with the idea that this would be the new capital, and so it was woven into the histories, and had it continued as the capital, the very landscape would have recalled the stories of the divine origins of the Royal family and the state of Yamato itself.

This was the stage on which Ohoama’s state was built. He, and his successors, didn’t just change the future path of the Yamato government. They rearranged the physical and temporal environment, creating a world that centered them and their government. I suspect that Ohoama didn’t originally consider that these wouldn’t be finished during his reign. That said, he came to power in his 40s, only slightly younger than his brother, who had just died. He would live to be 56 years old—a respectable age for male sovereigns, around that time. From a quick glance, Naka no Oe was about 45 or 46 years old, while Karu lived to about 57 or 58. Tamura only made it to 48. The female sovereigns seem to have lasted longer, with Ohoama’s mother surviving until she was 66 or 67 years old, and Kashikiya Hime made it to the ripe old age of 74. That said, it is quite likely that he thought he would make it longer. After all, look at all the merit he was accruing! Still, he passed away before he could see these projects fully accomplished. That would have to be left for the next reign—and even that wasn’t enough. The Fujiwara Capital would only be occupied for a short time before being abandoned about two reigns later, and the histories as we know them wouldn’t be complete for three more reigns.

So given all of this, let’s take another quick look at Ohoama himself and where he stands at this pivotal moment of Yamato history.When we look at how he is portrayed, Ohoama is generally lionized for the work he is said to have accomplished. I would argue that he is the last of three major figures to whom are attributed most of the changes that resulted in the sinification of the Yamato government.

The first is prince Umayado, aka Shotoku Taishi, who is said to have written the 17 article constitution, the first rank system, and the introduction of Buddhism. To be fair, these things—which may not have been exactly as recorded in the Chronicles—were likely products of the court as a whole. Many people attribute more to Kashikiya Hime, aka Suiko Tennou, as well as Soga no Umako. Of course, Soga no Umako wasn’t a sovereign, or even a member of the royal family, and Kashikiya Hime, aka Suiko Tennou, seems to have likewise been discounted, at least later, possibly due to the fact that she is thought to have come to power more as a compromise candidate than anything else—she was the wife of a previous sovereign and niece to Soga no Umako. Many modern scholars seem to focus more on the agency of Kashikiya Hime and suggest that she had more say than people tend to give her credit for. That said, Shotoku Taishi seems to have been the legendary figure that was just real enough to ascribe success to. That he died before he could assume the throne just meant that he didn’t have too many problematic decisions of his own to apparently work around.

The next major figure seems to be Naka no Oe, aka Tenji Tennou. Naka no Oe kicks off the period of Great Change, the Taika era, and is credited with a lot of the changes—though I can’t help but notice that the formal sovereign, Naka no Oe’s uncle, Karu, seems to have stuck with the new vision of the Toyosaki Palace and the administrative state while Naka no Oe and his mother moved back to the traditional capital. And when Naka no Oe moved the capital to Ohotsu, he once again built a palace more closely aligned to what we see in Asuka than the one in Naniwa, which brings some questions about how the new court was operating. But many of his reforms clearly were implemented, leveraging the new concepts of continental rulership to solidify the court’s hegemony over the rest of the archipelago.

Ohoama, as represented in the Chronicles, appears to be the culmination of these three. He is building on top of what his brother had implemented through the last three reigns. Some of what he did was consolidate what Naka no Oe had done, but there were also new creations, for which Ohoama is credited, even if most of the work was done outside of Ohoama’s reign, but they were attributed to Ohoama, nonetheless. Much of this was started later in Ohoama’s reign, and even today there seem to be some questions about who did what. Nonetheless, we can at least see how the Chroniclers were putting the story together.

There are a lot of scholars that point to the fact that the bulk of the work of these projects would actually be laid out in the following reigns, and who suggest that individuals like the influential Uno no Sarara, who held the control of the government in Ohoama’s final days, may have had a good deal more impact on how things turned out, ultimately. In fact, they might even have been more properly termed her projects—there are some that wonder if some of the attributions to Ohoama were meant to bolster the authority of later decrees, but I don’t really see a need for that, and it seems that there is enough evidence to suggest that these projects were begun in this period.

All of this makes it somewhat ironic that by the time the narrative was consolidated and published to the court, things were in a much different place—literally. The Fujiwara capital had been abandoned. The court, temples, and the aristocracy had picked up stakes and moved north. Fujiwara no Fuhito had come on the scene, and now his family was really taking off. This was not the same world that the Chronicles had been designed around.

And yet, that is what was produced. Perhaps there is a reason that they ended where they did.

From that point on, though, there were plenty of other projects to record what was happening. Attempts to control the narrative would need to do a lot more. We see things like the Sendai Kuji Hongi, with its alternative, and perhaps even subversive, focus on the Mononobe family. And then later works like the Kogoshui, recording for all time the grievances of the Imbe against their rivals—for all the good that it would do. With more people learning to write, it was no longer up to the State what did or did not get written down.

But that has taken us well beyond the scope of this reign—and this episode, which we should probably be bringing to a close. There are still some things here and there that I want to discuss about this reign—so the next episode may be more of a miscellany of various records that we haven’t otherwise covered, so far.

Until then if you like what we are doing, please tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

Thank you, also, to Ellen for their work editing the podcast.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Wittkamp, Robert F. (2026). Reading the Nihon Shoki: Chinese Encyclopedias, Source Criticism and Historical Writing in Old Japan. ISBN 9783695198436

Bentley, John R. (2025). Nihon Shoki: The Chronicles of Japan. ISBN 979-8-218634-67-4 pb

Bentley, J.R. (2020). The Birth of Japanese Historiography (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367809591

McCallum, Donald F. (2009). The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh-Century Japan. ISBN 978-0-8248-3114-1

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4.

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1