Jimmu Tennō, aka Iware Biko, subduing the forces of Nagasune Biko through the shining brilliance of the kite (a type of bird) that came down from Heaven.

Previous Episodes

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

So here we go! We are finally into the so-called “historical” portion of the Chronicles. This episode we follow the story of the legendary first sovereign of Yamato. Known to history as Jimmu Tennō (神武天皇) , that is a posthumous name, and the chronicles give us another name: Toyo Mikenu no Mikoto, aka Kamu Yamato Iware Biko no Mikoto. I know, it is a mouthful.

Language

I think this would be a good place to talk about a few things about names, titles, and the Japanese language—particularly the language in the chronicles. One of the problems working on the podcast is choosing just how to translate—or perhaps transliterate—the names and terms therein. We talked about this a little bit when we discussed language some episodes back, and I’ve mentioned the choice to use Himiko rather than Pimiko, even though the later is likely closer to the usage at the time.

In the Chronicles, they were also using Chinese characters in a combination of ways where they were sometimes used for meaning, but other times just for their sound to approximate Japanese words. The study of Old Japanese is a whole discipline that is extremely fascinating, but for the purposes of this podcasts, we’re going to try to keep it light. So we’ll just hit on some of the barest things you should know.

So first off, let’s talk about something called “rendaku”. This is the common practice of taking an unvoiced consonant and changing it to a voiced consonant. There is a good article about it on Tofugu: RENDAKU: WHY HITO-BITO ISN'T HITO-HITO

This has already shown up in some of the names and titles we have encountered—most notably “Hiko” (彦) and “Hime” (姫) (Prince and Princess, respectively), which are sometimes found as “Biko” or “Bime”, at least in modern pronunciation, so just realize that those are the same titles.

In addition, it is important to realize that Old Japanese had Perhaps most important is the “H” sound. Today, in modern Japanese, this is usually encountered as “Ha Hi Fu He Ho”, but it can transform into “P” or “B” as shown below.

| は | HA | ば | BA | ぱ | PA |

| ひ | HI | び | BI | ぴ | PI |

| ふ | FU | ぶ | BU | ぷ | PU |

| へ | HE | べ | BE | ぺ | PE |

| ほ | HO | ぼ | BO | ぽ | PO |

This is the only consonant that has three different forms—most simply have two, an unvoiced and a voiced form. But these three forms come from the fact that in the past there appear to have been just two—the “P” and “B” (and we aren’t even getting into some of the different distinctions in vowels).

The history behind this comes from the fact that the original sound was something like “P”, with a voiced sound of “B”. Over time, this “P” changed to something more like “F” (an unvoiced bilabial fricative still found in the character “FU”), then settled on “H”, with a few exceptions. We mention in the podcast how IPA became IFA/IHA and then IWA (岩). Similarly we have KAPA to KAFA/KAHA and then KAWA (川).

In addition, there is one other place were “P” changed into something else—often times being dropped altogether. Most notably is in various diphthongs and long vowels:

· “API”->”AF/HI” ->”AI”

· “APU”->”AFU”->”AU”

· “OPU”-> “OFU”->”OU”

· “OPO”->”OF/HO”->”OO”

So Ōkuninushi is more like Opokuninusi, and Amaterasu Ōkami is Amaterasu Opokami.

And, as I said, this doesn’t even get into the various vowels—where today there are only 5 vowels used in Japanese there appear to have been others used in early Japanese, but over time they were reduced to just those used today.

So that’s a little bit on the language.

The other part of the names, if you haven’t noticed, is that more often then not they appear to be titles. So “Iware Biko” is actually more like “Prince of Iware”—and it is telling, I think that “Iware” is a place in the Yamato basin. In fact, it is occupied by Shiki the Elder and Shiki the Younger when Iware Biko first arrives. Other names, like Usa-tsu-Hiko and Usa-tsu-Hime are the Prince and Prince (or male and female lord) of Usa. “Tsu” was often used as a possessive, similar to “No” in modern Japanese. So “Usa no Hiko” and “Usa no Hime” would be a way of thinking of them. By which it becomes clear that these are simply titles, and not “names” as we would think of them. This could be the name of any Lord or Lady of Usa.

This is not necessarily something that gets easier. While we do get names that are more properly names as we would think of them, Japanese writings regularly refer to someone by their title—possibly with a family name—or some other epithet. Examples of this include the famous Tomoe Gozen, Murasaki Shikibu, and Sei Shōnagon—women being the most common victims since their names are rarely recorded and so we often only have titles to go on. But even the famous “Shōtoku Taishi”, if he existed, is most commonly referenced by a title, not his name. And most of the sovereigns would be referenced as the sovereign of such-and-such palace, rather than any kind of actual name. In much of these stories, we seem to have those kinds of names, with the odd apparent exception, like “Nagasune Biko”, which can basically be translated as something like “Prince Longshanks”. But then he is also called Tōmi Biko—The Prince (of) Tōmi.

Geography

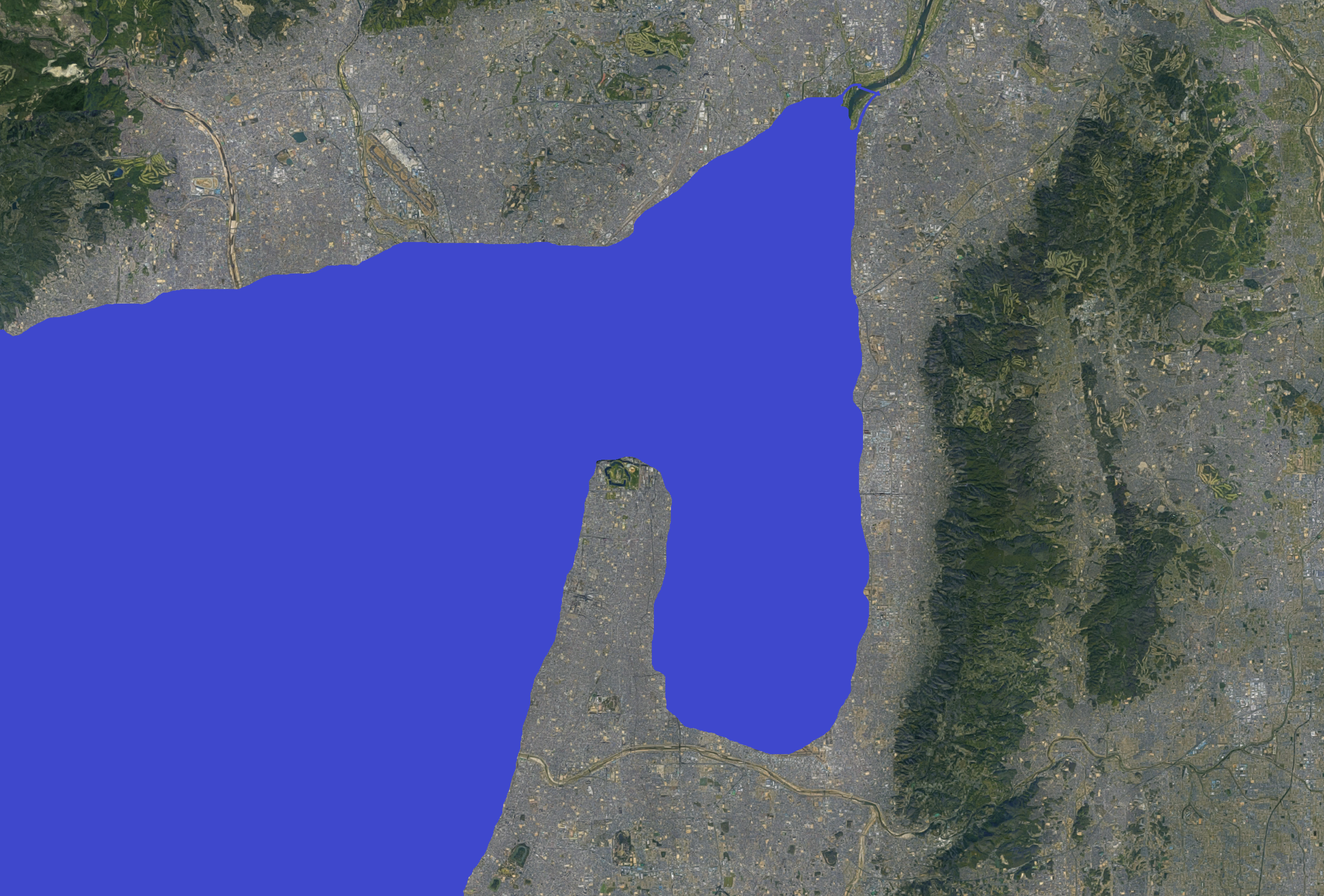

In the last podcast we talked a bit about the geography of the Nara Basin and a few of the places there. And I believe you can check on most of them. From Southern Kyushu you can find Usa, and then on to Aki (~Hiroshima Prefecture) and then on to Kibi (Okayama). Then Naniwa is an old name for Ōsaka, except here we come to a bit of an oddity. You see, back in the Kofun and Yayoi period, the area of most of Ōsaka was actually under water. Over time, these areas appear to have silted up, forming dry land (and then Ōsaka itself grew, building out into the bay). In the old days, though, there was a shallow bay—known as Kawachi Bay—that was actually nestled up along the edge of the mountains on the western edge of the Nara basin.

Modern Ōsaka

Rough approximation of t he extent of Kawachi Bay in ancient times.

So you can get an idea of just how the story unfolds—pulling straight up to the shoreline at the foot of the mountains and trying to make their way through. Note that this isn’t something explicitly mentioned in the Chronicles, but we have evidence of the ancient shoreline and it does provide some context for the stories.

Korean “sun crow” print (modern), from the author’s collection.

Yatagarasu - The Sun Crow

The sun crow is another great image from this passage—though the Chronicles really seem to focus more on its size than the other features by which it is better known. Nonetheless, at least in the eyes of later readers, the Yatagarasu would become an important symbol of the sun and of Japan itself.

Technically “Yatagarasu” just means the Great Crow, possibly indicating that it was of great size. “Yata-” is used similarly for other large or impressive items. More often, though, it isn’t its size which is its distinctive feature, but its three legs. This appears to come from the mainland, where the idea of the Yang Wu, or Sun Crow, has been around for some time.

Large sculpture in the shape of the gold foil “sun bird” disk, showing the fiery design. Photo by author.

Early on, for instance, we see a sun-bird disk coming out of the Jinsha ruins near modern Chengdu. The site flourished around the 10th century BCE, and the culture is generally assigned dates of 1200-650 BCE. Here they found numerous images of birds in disks, including a gold foil disk with four birds that appears to represent the sun. There is no clear indication of what these birds are, and they appear to have the proper number of legs. It could just be coincidence that they are birds in a sun disk, but it does seem similar to what we see later on. Of course, the birds could be some other bird than a crow—perhaps chickens or roosters, crowing at the sun, or something similar. They certainly appear to have long legs and necks, which could indicate some kind of crane or heron, but who knows?

From a Western Han tomb in Mawangdui there came a remarkably intact painted cloth covering for a coffin. The painting shows various symbols, including both a sun and a moon. The moon has a toad, but the sun has a black bird—likely a crow of some kind. Here we clearly see this bird in the sun, but it still only has the normal two legs. It could possibly be something else, but certainly feels like a crow, to me.

Detail of image from Wikimedia Commons that is labeled as being in the public domain.

And then, by at least the Tang dynasty (618-907), we see the three legged crow in the sun. Paintings of this three legged crow are seen in Tang dynasty tombs, along with pictures of the moon and other celestial objects.

Three-legged crow in a sun disk in a Tang Dynasty tomb. Photo by author.

Three-legged crow in a sun disk in a Tang Dynasty tomb. Photo by author.

It is not unreasonable to assume that the Japanese picked up on the three-legged crow from Chinese sources, likely filtered through the lens of the Korean Peninsula. Given the Wa people and their obsession with the sun, it seems only natural that they would find a use for the imagery. That said, whether or not there was some other legendary beast called Yatagarasu that was then conflated with Yang Wu, I could not say.

References

· Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

· Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

· Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

· Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

· Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1