Previous Episodes

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we’ll take a look at the extremely short reign of Mizuha Wake, aka Hanzei Tennō, and then on to the succeeding reign of Ingyō Tennō. There may be some slight spoilers in here for the episode (but, again, it is history, so do spoilers really exist?) so I recommend you listen to the episode first. Below you should find some explanations of the various individuals involved and I’ll try to lay out their family connections as best I can.

An important thing to note is that this period is still highly questionable. We’ll get into the continental sources in a bit—probably in another episode or two. Once we do, and we bring this all together, I think it will both help with some context but will also likely muddy the waters a bit more.

Midzuha Wake

We met Midzuha Wake back during the reign of his brother, Izaho Wake, and really there is little to say about him here. When he finally comes to the thrown he reigns, peacefully, for five years. That’s about it.

Oasatsuma Wakugo no Sukune

The youngest son of Ōsazaki no Mikoto and Iwa no HIme, making him the full brother to both Izaho Wake and Midzuha Wake. He was struck ill in his youth and we are told in the Nihon Shoki that he lost command of his limbs. Later he would recover thanks to continental medicine.

Ōkusaka no Miko

Another son of Ōsazaki no Mikoto, but through Kaminaga Hime rather than Iwa no Hime. His sister, Kusaka no Hatahi, had been married to Izaho Wake and Ōkusaka would eventually marry their daughter, his niece, Nakashi Hime, but apparently that was all well and good by the standards of the day.

Osaka no Nakatsu Hime

Supposedly a daughter of Homuda Wake and one of his many wives, Kaguro Hime, if the lineage in the Chronicles is to be believed one suspects she was nearly old enough to be Oasatsuma’s mother, despite the fact that they were married. It is quite possible that her lineage was changed so that she could be queen and thus her offspring could inherit the throne.

Sotowori Hime

Also referred to as “Oto Hime”, but that really just means “younger princess”, she was the younger sister to Osaka no Nakatsu Hime, we are told. Her name is supposedly an epithet describing her radiant beauty, though it may have also referred to how she was living outside, or “soto”, from the palace.

Nakatomi no Ikatsu no Omi

Ikatsu is referred to as a toneri, meaning a palace servant. As such, we can assume that the “Omi” in his name was a family kabane, rather than marking him as a literal minister. The Nakatomi family would eventually become known as powerful ritualists at court and eventually a branch of that family would break off and become the Fujiwara. It is unclear if the “Omi” kabane was actually something that Ikatsu would have used at this time, and that may be an anachronism.

Yamato no Atae no Agoko

We’ve already met Agoko in previous reigns, and though he doesn’t have much of a part, here, it is still interesting that he makes even a cameo appearance.

On Poetry

This episode we see the use of poetry—specifically tanka—used in wooing a woman. The format that we see, where a man goes and secretly listens to a woman, and then responds to her poem with one of his own, feels particularly trope-filled. This is the kind of thing that filled the various romances of the Heian period, around the time of the Tale of Genji, and it is interesting to see the format so long ago.

I would note, however, that poems from this period of the Chronicles can still be rough, and 5-7-5/7-7 meter that one might expect is not always present. It is possible this is an error in the transcription of some of the poems, but it is also the case that this meter was not always adhered to strictly, with oral flourishes of one kind or another likely making up for it in the reading by either combining multiple morae or lengthening them appropriately.

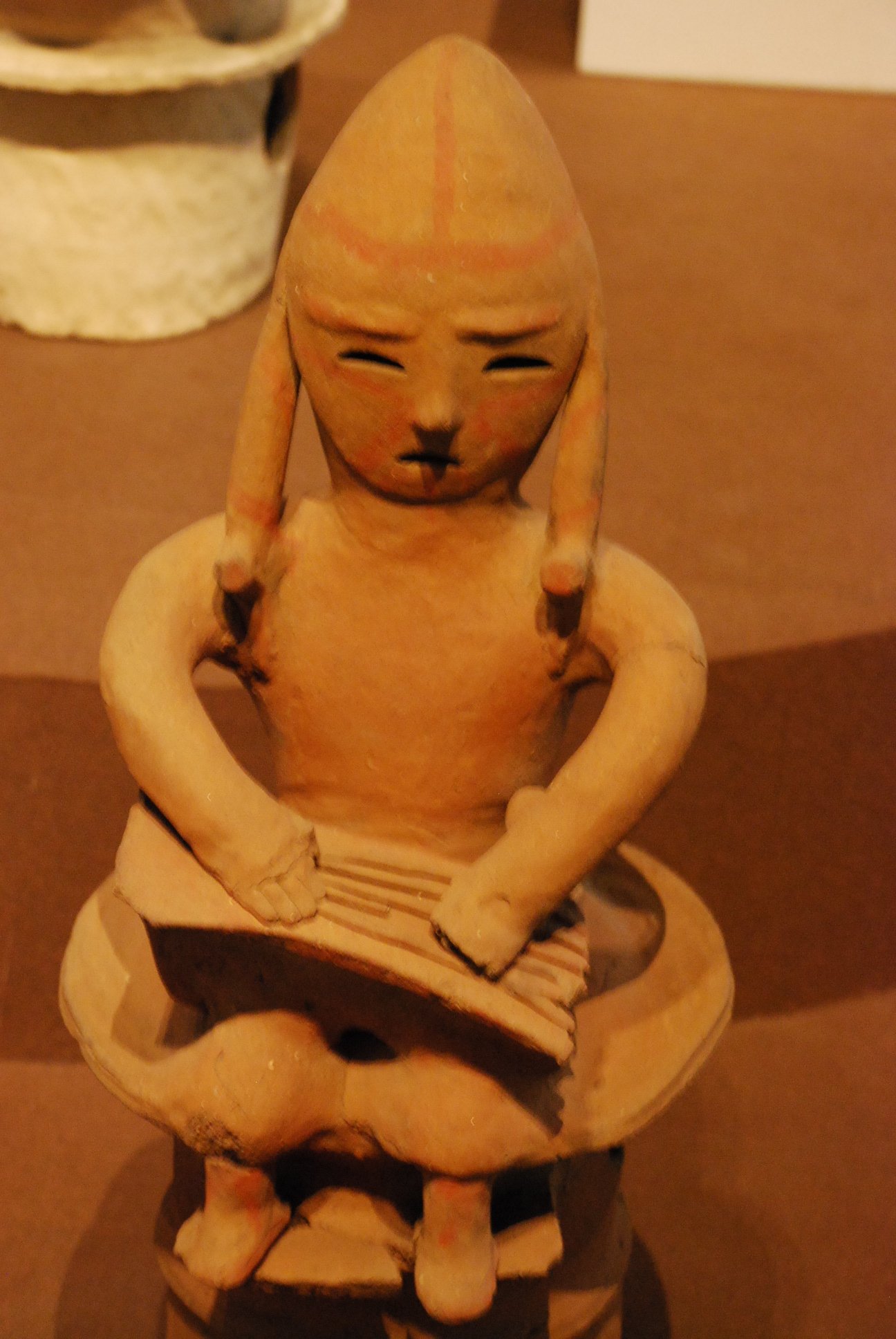

The Koto

At one point, we are told that the sovereign is playing the koto, a type of zither—a horizontal stringed instrument usually played while seated. Modern koto are very similar to the Chinese guzheng, though the latter has more strings. An earlier version also existed, known later as the wagon (和琴), and I suspect that this is the instrument that is being referenced in the Nihon Shoki. It was apparently smaller than a modern koto, and had even fewer strings, but it was still a very similar instrument.

References

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1