Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

Taking a break from the Chronicles while I pull together some more research, as we are starting to enter much more impactful period with a lot of change. So instead, I’m presenting you a glimpse at a recent tour we did following the old route to Japan mentioned in the “Gishiwajinden”, or the Wa records from the Weizhi. This described the 3rd century journey from the Korean peninsula down to “Yamatai” (probably “Yamateg/Yamato” at the time), and includes relatively clear directions from “Guyahan” to “Tuma” to “Iki”, then “Maturo”, “Ito”, and “Na”. These have all been largely agreed upon as being part of the western edge of Kyushu.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is Gishiwajinden Self-Guided Tour: Geumgwan Gaya.

For the next several episodes we are taking a bit of a detour from the narrative of the Chronicles. After all, with the coup of 645 that we covered a couple of episodes ago, we are about to dive into the period known as “Taika” or “Great Change”. Prince Naka no Oe and Nakatomi no Kamako were not just assassins—they had plans that went beyond just cutting the head off the powerful Soga house. It’s an eventful time, with a lot of changes, though some of those would take time to really come to fruition and before I get into all of that there is a bit more research that I want to do to figure out the best way to lay that out for you.

And so I figured we would take a little detour for a few episodes, to share with you a special trip that Ellen and I recently took, reproducing – in a modern way – some of the earliest accounts we have about crossing over to the archipelago: the Gishiwajinden, the Japanese section of the Weizhi. We talked about this chronicle back in episode 11: it describes all the places one would stop when leaving the continent, from kingdoms on the peninsula and across the smaller islands of the archipelago before landing in what we currently call Kyushu.

And Ellen and I did just that: we sailed across the Korean straits, from the site of the ancient kingdom of Gaya in modern Gimhae, to the islands of Tsushima and Iki, then on to modern Karatsu and Fukuoka, passing through what is thought to be the ancient lands of Matsuro, Ito, and Na. It was an incredibly rewarding journey, and includes plenty of archaeological sites spanning the Yayoi to Kofun periods—as well as other sites of historical interest. It also gets you out to some areas of Japan and Korea that aren’t always on people’s list, but probably should be.

So for this first episode about our “Gishiwajinden Jido Toua” – our Gishiwajinden Self-Guided Tour – we’ll talk about the historical sites in Gimhae, the site of ancient Geumgwan Gaya, but also some of the more modern considerations for visiting, especially on your own.

By the way, a big thank you to one of our listeners, Chad, who helped inspire this trip. He was living on Iki for a time and it really made me think about what’s out there.

This episode I’ll be focusing on the first place our journey took us, Gimhae, South Korea. Gimhae is a city on the outskirts of modern Pusan, and home to Pusan’s international airport, which was quite convenient.

This is thought to be the seat of the ancient kingdom of Gaya, also known as “Kara” in the old records. In the Weizhi we are told of a “Guyahan”, often assumed to be “Gaya Han”, which is to say the Han—one of the countries of the peninsula—known as Guya or Gaya. This is assumed to mean Gaya, aka Kara or Garak, and at that time it wasn’t so much a kingdom as it was a confederation of multiple polities that shared a similar material culture and locations around the Nakdong river. This is the area that we believe was also referenced as “Byeonhan” in some of the earliest discussions of the Korean peninsula.

By the way, while I generally believe this area was referred to as “Kara”, “Gara”, or even “Garak”, originally, the modern Korean reading of the characters used is “Gaya”, and since that is what someone will be looking for, that’s what I’ll go with.

History of the Korean peninsula often talks about the “Three Kingdoms” period, referencing the kingdoms of Baekje, Silla, and Goguryeo. However, that is a very simplistic view of the ancient history of the archipelago. Numerous small polities existed without a clear, persistent overlord outside of those three larger polities, and even they were not always quite as grand as the later histories would like to make them out to be.

Gaya is often referred to as the “Gaya Confederacy” by modern historians, at least for most of its existence, and refers to a number of polities including Daegaya, Ara, etc., and may also include “Nimna”, though where exactly that was is a topic of great debate, with some claiming that it was just another name for what later was known as Geumgwan Gaya, and other suggestions that it was its own polity, elsewhere on the coast. This isn’t helped by the nationalist Japanese view that “Nimna” was also the “Mimana Nihonfu”, or the Mimana controlled by Japan, noted in the Nihon Shoki, and used as the pretext for so many of the aggressions perpetrated on the continent by Japan.

These all appear to have been individual polities, like small city-states, which were otherwise joined by a common culture. Although the Samguk Yusa mentions “King Suro” coming in 42 CE, for most of its history there wasn’t really a single Gaya state as far as we can tell. It is possible that towards the 5th and early 6th centuries, Geumgwan Gaya had reached a certain level of social complexity and stratification that it would classify as a “kingdom”, but these definitions are the kinds of things that social scientists would argue about endlessly.

Evidence for a “Kingdom” comes in part from the way that Geumgwan Gaya is referenced in the Samguk Sagi and other histories, particularly in how its ruling elite is referred to as the royal ancestors of the Gimhae Kim clan. Proponents also point to the elaborate graves, a large palace site (currently under excavation and renovation), the rich grave goods found in the tombs thought to be those of the royal elites, etc. Other scholars are not so sure, however, and even if there was a nominal kingdom, it likely did not last very long before coming under the rule of Silla in the 6th century.

Unlike the other kingdoms—Baekje, Silla, and Goguryeo; the “Samguk”, or three countries, of the “Samguk Sagi”—Gaya does not have its own record in the histories. The Samguk Yusa, which is of interest but also problematic in that it was clearly more about telling the miraculous tales of Buddhism than a strictly factual history, does have a bit about Gaya. The author of the Samguk Yusa, the monk Ilyeon, claimed that the information there was pulled from a no longer extant record called the Gayakgukki, or Record of the Gaya Kingdom, but the actual stories are not enough to tell us everything that happened. Most of what we know comes from members of the Gaya Confederacy popping up in the records of other nations, including Baekje, Silla, Goguryeo, and Yamato. For example, there are references in the Gwangaetto Stele from the 5th century, as well as plenty of references in the Nihon Shoki and the records in the Samguk Sagi. This is a little bit better than some of the other groups mentioned as being on the Korean peninsula that are often referred to only one time before being completely forgotten.

For us, the importance of Gaya is its links with Yamato. Although it would seem that Nimna, in particular, had close ties with Yamato it is noteworthy that the Japanese word for the continent and things that would come from there—including the later Tang dynasty—is “Kara”. “Kara-fu” generally refers to something that comes from China, but only because those things originally came through the peninsula and through Kara, or Gaya. The port on Kyushu where the goods likely arrived before continuing up to modern Fukuoka is even today known as “Karatsu”, or “Kara Port”. This lends credence to the idea that Nimna was likely at least a member of the Gaya confederacy.

There are also deep similarities in many material items found in the peninsula and in the area of the Nakdong peninsula, including pottery, armor, horse gear, etc. At the very least this indicates a close trading relationship, and combined with the account in the Weizhi, emphasizes the idea that this was likely the jumping off point for missions to the archipelago and vice versa.

Perhaps more controversial is the idea that at least some members of the Gaya Confederacy, or the Byeonhan cultural group before it, may have been speakers of some kind of proto-Japonic. There are also some that suggest there may have been ethnic Wa on the peninsula at an early point as well. However, I would note that the Weizhi refers to this area specifically as being part of the “Han”, and that it was the jumping off point to find the lands of the Wa and eventually the lands of Yamato (or Yamatai), so make of that what you will. All of this is well after the introduction of rice cultivation in Japan, focusing on the 3rd century onward, roughly corresponding to what we think of as the Kofun Period in Japan, and which was also a period of ancient mound-building on the Korean peninsula as well.

All that aside, it is clear that Gaya was an important part of the makeup of the early Korean peninsula, and that much of that history is on display in modern Gimhae.

Gimhae is one of plenty of places on the Korean peninsula for anyone with an interest in ancient history. Besides the various museums, like thate National Museum in Seoul, there are sites like Gyeongju, the home of the tombs of the Silla kings and the ancient Silla capital, and much more. Gimhae itself is home to the Royal Gaya Tombs, as well as archaeological remnants of an ancient settlement that was probably at least one of the early Gaya polities.

As I noted, Gimhae is more accurately the site of what is known in later historical entries as Geumgwan Gaya. The earliest record of the Weizhi just says something like “Gü-lja-han” which likely means “Gaya Han”, or Gaya of Korea, referring at the time to the three Han of Mahan, Jinhan, and Byeonhan. That may or may not have referred to this particular place, as there are other Gaya sites along the coast and in the upper reaches of the Nakdong river. However, given its placement on the shore, the site at Gimhae seems to have a good claim to be the point mentioned in the Wei Chronicles, which is why we also chose it as the first site on our journey.

The characters for “Gimhae” translate into something like “Gold Sea”, but it seems to go back to the old name: Geumgwan, as in Geumgwan Gaya. It is part of the old Silla capital region. “Geum” uses the same character as “Kim”, meaning “Gold” or “Metal”. This is also used in the popular name “Kim”, which is used by several different lineage groups even today. The “Sea” or “Ocean” character may refer to Gimhae’s position near the ocean, though I don’t know how relevant that was when the name “Gimhae” came into common usage.

The museums and attractions around Gimhae largely focuses on the royal tombs of the Geumgwan Gaya kingdom, which in 2023 were placed, along with seven other Gaya tomb sites, on the UNESCO list of world heritage sites. Since they’re so newly added, we did not see the kind of omnipresent UNESCO branding that we are used to seeing elsewhere, such as Nikko Toshogu or Angkor Wat, but taxi drivers certainly knew the UNESCO site and museum.

For anyone interested in these tombs and in Gaya’s early history, there are two museums you likely want to visit. First off is the National Museum, which covers a wide swath of history, with tons of artifacts, well laid out to take you through the history of the Gaya Confederacy, from early pre-history times through at least the 7th century. There is also a separate museum that specifically covers the Daeseong-dong tombs, which lay upon a prominent ridge on the western side of the city, north of a Gaya era settlement with a huge shell midden found at Bonghwang-dong, to the south, nearby an ongoing excavation of a potential palace site.

These museums have some excellent displays, including pottery, metalwork, horse gear, armor, and even parts of an ancient boat. As I noted earlier, these show a lot of similarity to items across the strait in the archipelago, though it is clear that Gaya had a lot more iron than their neighbors —in fact, they had so much that they would often line the bottom of tombs with iron ingots. The displays emphasize that Gaya was really seen as a kind of ironworking center for the region, both the peninsula and the archipelago.

The tombs, likewise, have some similarity to those in the archipelago—though not in the distinctive, keyhole shape. Early tombs, from the 1st to 2nd century, were simply wooden coffins dug in a pit with a mound on top. This became a wooden lined pit, where bodies and grave goods could be laid out, and then, in the 3rd century, they added subordinate pits just for the various grave goods. In the 5th century this transitioned to stone-lined pit burial, and in the 6th century they changed to the horizontal entry style stone chamber tomb, before they finally stopped building them. These seem to be similar to what we see in Silla, with wooden chamber tombs giving way to the horizontal entry style around the 5th and 6th centuries. Meanwhile, Baekje and Goguryeo appear to have had horizontal style tombs for some time, and that may have been linked to Han dynasty style tombs in the area of the old Han commanderies—which I suspect might have spread with the old families of Han scribes and officials that were absorbed into various polities.

It is interesting to see both the similarities and differences between Gaya and Wa tombs in this period, particularly the transition to the horizontal entry style tombs, which I suspect indicates an outside cultural influence, like that of Silla—something that would also influence the burials in the archipelago. At first, in the 4th to 5th centuries, we just see these style tombs starting to show up in Kyushu, particularly in the area of modern Fukuoka—one of the areas that we will hit at the end of this journey from the peninsula to the archipelago. That may be from contact with Baekje or Goguryeo, or even from some other point, it is hard to tell. By the 6th century, though, just as Silla and Gaya were doing, it seems that all of the archipelago was on board with this style of internal tomb structure.

Another tomb style you can find in Gimhae is the dolmen. These are megatlithic—or giant rock—structures where typically a roof stone is held up by two or more other large stones. In some cases these may have been meant as an above-ground monument, much like a structure such as Stonehenge. On the other hand, in some cases they are the remains of a mound, where the mound itself has worn away. Unfortunately, there was not as much information on them—it seems that dolmens were originally used before the mounded tomb period, but just what was a free-standing dolmen and what was an internal mound structure exposed by the elements I’m not sure I could say.

If you visit the Daeseong-dong tombs, one of the things you may notice is the apparent lack of a tomb mound. The attached museum explains much of this, though, in that over time the wooden pit-style tombs would often collapse in on themselves. That, plus erosion and continued human activity in an area would often mean that, without upkeep, there would eventually be no mound left, especially if it wasn’t particularly tall to start with.

In an example where something like this might have happened, there is at least one tomb in the group that was clearly dug down into a previous burial chamber. The excavators must have realized they were digging into another tomb, given that they would have pulled up numerous artifacts based on what was later found at the site, but they still carried on with the new tomb, apparently not having any concern for the previous one. After all, there was only so much room up on the ridge for burials, at least towards the later periods. This pair of “interlocking” tombs is housed inside a building with a viewing gallery, so you can see their layout and how the grave goods would have been arranged in period.

One tomb that apparently kept a mound of some kind would appear to be that attributed to King Suro. King Suro is the legendary founder of Geumgwan Gaya, mentioned in the 13th century Samguk Yusa, which was using an older record of the Gaya Kingdom as their source. The area where the tomb is found is said to match up with the description in the Samguk Yusa, but I could find no definitive evidence of a previous tomb or what style it was—let alone the question of whether or not it was the tomb of King Suro of Geumgwan Gaya. It was still a very impressive compound, though it seems most of the buildings are likely from a much more recent era.

I suspect that King Suro remained an important story for the Gimhae Kim clan. That clan, as mentioned earlier, claimed descent from the Kings of Geumgwan Gaya, of whom King Suro was supposedly the first. It is noteworthy that the Kim family of Geumgwan Gaya, known as the Gimhae Kim clan, was granted a high rank in Silla because they claimed descent from the “Kings” of Geumgwan Gaya. As such Munmyeong, the sister of Kim Yusin, the general who helped Silla take over the peninsula, was apparently considered an appropriate consort to King Muyeol, and her son would become King Munmu. This brought the Gimhae Kim clan into the Gyeongju Kim clan of Silla.

Kim Busik, who put together the Samguk Sagi, was a member of the Gyeongju Kim clan, which claimed descent from those same kings. He had plenty of reason to make sure that the Silla Kings looked good, and may have also had reason to prop up the leaders of Geumgwan Gaya as well, given the familial connections. That said, there do seem to be some impressive tombs with rich grave goods, so there is that.

In 1580 we are told that Governor Kim Heo-su, who counted himself a descendant of the Gimhae Kim clan, found the tomb of King Suro and repaired it, building a stone altar, a stone platform, and a tomb mound. It is unclear from what I can find, though, just what he “found” and how it was identified with what was in the Samguk Yusa. Even if there was something there, how had *that* been identified? There seems to be plenty of speculation that this is not the actual resting place of the legendary king, Kim Suro, but it is certainly the place where he is worshipped. The tomb was apparently expanded upon in later centuries, and today it is quite the facility, though much of it seems relatively recent, and hard to connect with the actual past.

More important for that is probably what they was found at Bonghwang-dong. On this ridge, south of the tomb ridge, were found traces of buildings including . These included pit style dwellings along with post-holes, indicating raised structuresdwellings of some sort. Today you can go and see interpreted reconstructions, based in part on some pottery models that had also been found from around that period. Reconstructed buildings sit on either side of a hill, which is the main feature of a modern park. It is a good place to get a sense of what was around that area, and you can hike to the top of the hill, which isn’t that difficult a journey. The trees do obstruct the view, somewhat, but you get a great sense for what a community there might have been like. As I mentioned before, there is also a large excavation being carried out on what is believed to be some kind of royal palace structure, but unfortunately we likely won’t know much more until later.

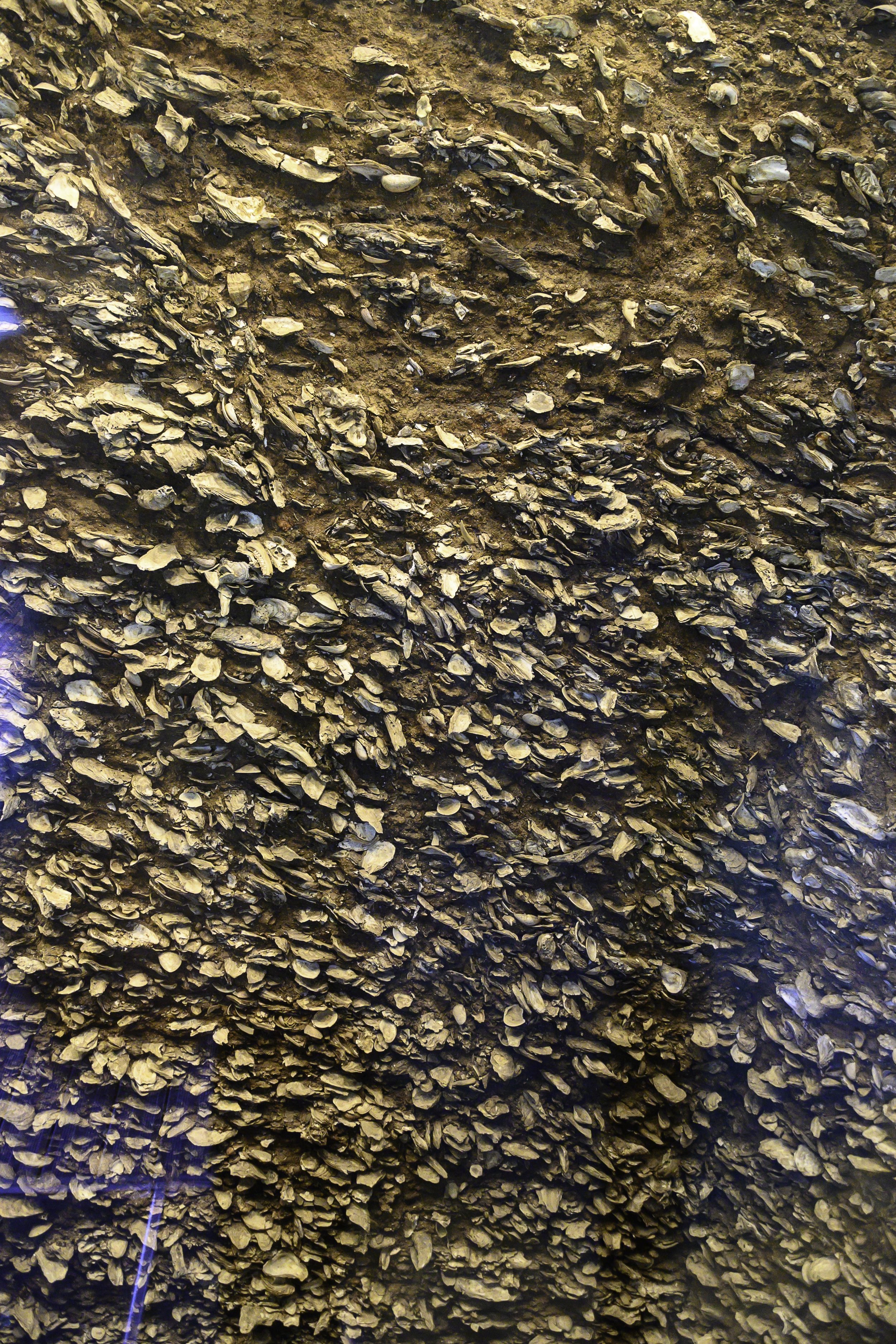

Also next to the settlement is a giant shell mound. We are talking over a football field long and several stories high of shells and bone, along with discarded pottery and other such things. Unfortunately, for whatever reason, the contents of the shell mound appear to have been mixed at various stages, but it is still impressive, and they have an excellent display where you can see the mound cut away to demonstrate what a shell mound might look like.

The shell mound apparently existed from the 1st to the 4th centuries. This feels odd to me, given that I normally think of shell mounds as more connected to Jomon and similar sites, but it also makes sense that a community—particularly one with easy access to the sea—would have a lot of shells and it isn’t like they had trash collectors coming to take away their garbage.

Which brings me to another point: Back in its heyday, Geumgwan Gaya was clearly on or very near the sea. In modern times you can certainly see islands off the coast from the tops of some of these hills—and from the top of a mountain one might even make out Tsushima on a clear day. However, today that ocean is several miles out.

Back in the time of the Geumgwan Gaya, however, things were likely different. The Nakdong river would have emptied out to the east into a large bay, with Geumgwan Gaya sitting comfortably at its head, with mountains on three sides and the ocean on the fourth. This would have made it a great as a port town, as it not only had access to the Korean straits and the Pacific Ocean, but it also sat at the head of the river that connected many of the sites believed to be related to the ancient Gaya confederacy.

Over time, however, the bay silted up, and/or sea levels dropped, and the area that would become the heart of modern Gimhae would find itself farther and farther away from the ocean, through no fault of their own. That must have put a damper on their trade relationships, and I can’t help but wonder if that was one of the reasons they eventually gave in to Silla and joined them.

With its place at the head of the Nakdong river, Silla’s control of Geumgwan Gaya likely made the rest of the Gaya polities’ absorption much more likely, as most of the Gaya polities appear to have been laid out around the Nakdong river. That would have been their lifeline to the ocean and maritime trade routes. Without a cohesive state, they may not have been able to resist the more organized and coordinated armies of groups like Silla and Baekje, eventually falling under Silla’s domain.

Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be much online in English about Gimhae beyond the ancient connection to Geumgwan Gaya. Specifically, I didn’t find a lot of clear historical information about the city after coming under Silla rule. It was apparently one of the “capitals” of the Silla region under Later or Unified Silla. Though Silla tried to form the people of the three Han of Baekje, Goguryeo, and Silla into a unified state, its central authority would eventually break down. Baekje and Goguryeo would be briefly reconstituted before the Later Goguryeo throne was usurped by a man who would be known as Taejo, from Gaesong. He would lead the first fully successful unification effort, and from the 10th century until the 14th the state was known as “Goryeo”, from which we get the modern name of “Korea”. Goryeo started in Gaesong, but also rebuilt the ancient Goguryeo capital at Pyongyang, both up in what is today North Korea. It eventually came under the thumb of the Mongol Yuan dynasty, and when that dynasty was overthrown by the Ming, Goryeo experienced its own instability, resulting in the Joseon dynasty, which moved the capital to the area of modern Seoul. Given modern tensions between North and South Korea, I suspect that there is a fair bit of politics still wrapped up in the historiography of these periods, especially with each modern state having as their capitals one of the ancient capital city sites.

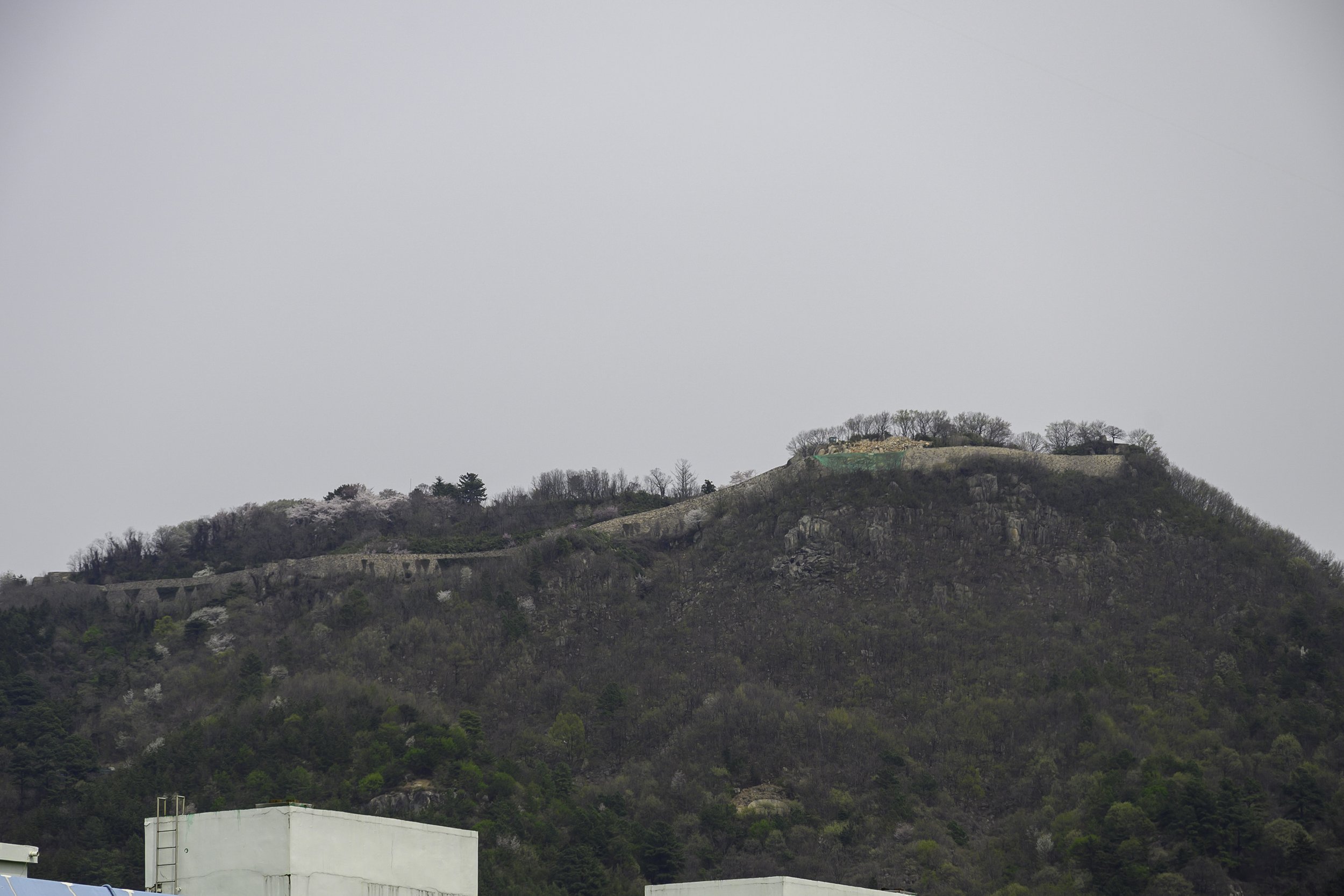

As for Gimhae, I have very little information about the city during the Goryeo period. Towards the end of the 14th century, we do see signs of possible conflict, though: There was a fortress built on the nearby hill, called Bunsanseong, in about 1377, though some claim that an older structure was there since the time of the old Gaya kingdom, which would make sense, strategically. This fortress was severely damaged during Hideyoshi’s invasion of Korea in the late 16th century—a not uncommon theme for many historical sites on the peninsula, unfortunately—and repaired in 1871. The walls can still be seen from the city below.

Stone walls were placed around the city in 1434 and improved in 1451. Excavations on the wall were carried out in 2006 and the north gate, which was first renovated in 1666, was restored in 2008. You can still visit it, north of the international markets, which includes a wet market along with various restaurants offering specialties from around Northeast Asia, including places like Harbin, in China.

Near the north gate there is also a Confucian school, or hyanggyo. The first iteration was probably built during the Goryeo dynasty, but whatever was there in the 16th century was also destroyed during Hideyoshi’s invasion. It would later be rebuilt in 1688 and relocated to the east until it burned down in 1769. The following year it was rebuilt in its current location, north of the city gate. The school contains examples of the classrooms along with a central Confucian shrine, and there are some similarities with similar Edo period institutions in Japan, which also based themselves off of a Confucian model.

For those interested in more recent history, you may want to check out the Gimhae Folk Life Museum. This covers some of the more recent folk traditions, clothing, and tools and home goods used up until quite recent times. It may not be as focused on the ancient history of the area, but it certainly provides some insight into the recent history of the people of Gimhae.

Today, Gimhae is a bustling city. Not quite as big and bustling as Pusan or Seoul, but still quite modern. You can easily get there by train from Busan or Gimhae International Airport, and there are plenty of options to stay around the city such that you can walk to many of the historical sites.

For those used to traveling in Japan, there are both similarities and differences. Alongside the ubiquitous Seven Eleven chains are the CU chain, formerly known as FamilyMart, and GS25, along with a few others. Trains are fairly easy to navigate if you know where you want to go, as well – there’s a convenient metro line that connects the airport to Gimhae city proper, and has stops right by the museums. , and you can mostly get around by train—you can even take thThe KTX, the Korean Train eXpress, the high-speed rail, which includes a line from Seoul to Busan. And don’t worry, from our experience there are no zombies on the train to- or from- Busan.

Of course, in Korea they use Hangul, the phonetic Korean alphabet. It may look like kanji to those not familiar with the language but it is entirely phonetic. Modern Korean rarely uses kanji—or hanja, as they call it—though you may see some signs in Japanese or Chinese that will use it here and there. In general, though, expect things to be in Korean, and there may or may not be English signs. —tHowever, hough most of the historical sites we visited had decent enough signage that we only occasionally had to pull out the phone for translation assistance, and the museums are quite modern and have translation apps readily available with QR codes you can scan to get an English interpretation..

Speaking of phones, make sure that you have one that will work in Korea or consider getting a SIM card when you get in, as you will likely want it for multiple reasons. That said, a lot of things that travelers rely on won’t work in Korea unless you have the Korean version. For instance, Google Maps will show you where things are but it can’t typically navigate beyond walking and public transit directions. For something more you’ll want the Korean app, Naver. We did okay, for the most part, on Google Maps, but Naver is specifically designed for South Korea.

Likewise, hailing a cab can be a bit of a chore. Don’t expect your Uber or Lyft apps to work—you’ll need to get a Korean taxi app if you want to call a taxi or you’ll need to do it the old fashioned way—call someone up on the telephone or hail one on the streets, which can be a tricky business depending on where you are.

On the topic of streets: In Gimhae, many of the streets we were walking on did not have sidewalks, so be prepared to walk along the side of the road. We didn’t have much trouble, but we were very conscious of the traffic.

Another note in Gimhae is the food. Korea is host to a wide variety of foods, and Gimhae can have many options, depending on what you are looking for. Near our hotel there were traditional Korean restaurants as well as places advertising pizza, Thai, and burgers. Up in the main market area, you can find a wide variety of food from around Asia. Vietnam, Sri Lanka, Uzbekistan, Nepal, and many more were represented, as well as Russian and Chinese cuisines.

That said, our breakfast options were not so bountiful. Our hotel, which gave us our own private hot tub, like a private onsen, did not serve breakfast, but . Tthere were a few cafes around where you could get a drink and a light meal in the morning, and there were some pork Gukbab places, where you would put cooked rice in a pork bone broth for a hearty and delicious morning meal. That said, if you waited a little later, there is a Krispy Kreme for those craving donuts, and a few French-inspired Korean bakeries, such as the chain, Tours les Jours, which is always a tasty became one of our go-to spots.

If you prefer a wider variety of food you can choose to stay in Busan proper, instead. It isn’t that far, and you can take the train over to Gimhae in the morning. However, Busan has more options than Gimhae, but it does mean taking a train over to see the sites. I would recommend at least two days to see most of the Gaya related sites, and maybe a third or fourth if you want to chase down everything in the city.

There is also an interesting amusement park that we did not get the chance to experience but may be of interest: the Gimhae Gaya Theme Park. This appears to be a series of interpretations of different Gaya buildings along with a theme park for kids and adults, including rope bridges, light shows, and some cultural performances. It looked like it might be fun, but since we had limited time we decided to give it a pass this time around.

In Busan, there are many other things to do, including museums, folk villages, and an aquarium along the beach. Busan station is also conveniently located next to the cruise port, where ships depart daily for Japan. This includes typical cruise ships, as well as various ferries. For instance, there is a ferry to Hakata, in Fukuoka city, as well as an overnight ferry that takes you through the Seto Inland sea all the way to Osaka. For us, however, we had booked the jetfoil to Hitakatsu, on the northern tip of Tsushima island – a very modern version of the Gishiwajinden account of setting sail in a rickety ship.

Unfortunately, as we were preparing for our journey, disaster struck—the kind of thing that no doubt befell many who would dare the crossing across the waters. Strong winds out in the strait were making the water choppy, and it was so bad that they decided to cancel all of the ferries for that day and the next. It made me think of the old days, when ships would wait at dock as experienced seamen kept their eye on the weather, trying to predict when it would be fair enough to safely make the crossing. This was not always an accurate prediction, though, since on the open ocean, squalls can blow up suddenly. In some cases people might wait months to make the crossing.

Since Wwe didn’t have months, however, and had a lot to see in Tsushuma, so we opted for another, very modern route: . Wwe booked airplane tickets and left from Gimhae airport to Fukuoka, where we transitioned to a local prop plane for Tsushima. You might say: why not just fly to Tsushima? But Tsushima doesn’t have an international airport, and only serves Japanese domestic destinations. Hence the detour to Fukuoka, where we went through Japanese immigration and had a very nice lunch while we waited for our second, short flight.

Even that was almost cancelled due to the winds at Tsushima, with a disclaimer that the plane might have to turn around if the weather was too bad. Fortunately, we were able to make it, though coming into Tsushima airport was more than a little hair-raising as the small plane came in over the water and cliffs and dodged some pretty substantial updrafts before touching down on a tiny airstrip.

And with that, we made our crossing to Tsushima island. Or perhaps it is better to call them “islands” now, since several channels have been dug separating the north and south parts of Tsushima. It wasn’t quite how we had planned to get there, but we made it – and that kind of adaptability is very much in keeping with how you had to travel in the old days!.

One more comment here about the Korean Peninsula and Tsushima: while we never had a day clear enough, it seems obvious that from a high enough vantage point in Gimhae or Gaya, one could see Tsushima on a clear day. This is something I had speculated, but as we traveled it became clear. Tsushima is actually closer to the Korean Peninsula than to Kyushu, a fact that they point out. And so it was likely visible enough to people who knew what they were looking for.

And yet, I imagine being on a small boat, trying to make the journey, it must have been something. You hopefully had a good navigator, because if you went off in the wrong direction you could end up in the East Sea—known in Japan as the Japan Sea—or worse. If you kept going you would probably eventually reach the Japanese archipelago, but who knows what might have happened in the meantime. It is little wonder that ships for the longest time decided to use Tsushima and Iki as stepping stones between the archipelago and the continent.

And with that, I think we’ll leave it. From Gimhae and Pusan, we traveled across to Tsushima, which has long been the first point of entry into the archipelago from the continent, often living a kind of dual life on the border. Tsushima has gotten famous recently for the “Ghost of Tsushima” video game, set on the island during the Mongol Invasion – we haven’t played it, but we understand a lot of the landscape was reproduced pretty faithfully.

From there we (and the ancient chroniclers) sailed to Iki. While smaller than Tsushuma, Iki was likely much more hospitable to the Yayoi style of rice farming, and the Harunotsuji site is pretty remarkable.

Modern Karatsu, the next stop, is literally the Kara Port, indicating that the area has deep connections to the continent. It is also the site of some of the oldest rice paddies found on the archipelago, as well as its own fascinating place in later history.

Continuing north along the coast of Kyushu is another area with evidence of ancient Yayoi and Kofun communities in Itoshima, thought to be the ancient country of Ito. Here you can find some burial mounds, as well as the site where archaeologists found one of the largest bronze mirrors of the ancient archipelago. Finally, we ended up in Fukuoka, where the seal of the King of Na of Wa was found.

We ended our trip in Fukuoka, but the historical trail from Na, or Fukuoka, to quote-unquote “Yamatai” then goes a bit hazy. As we discussed in an earlier episode, there are different theories about where Yamatai actually was. There is the Kyushu theory, which suggests that Yamatai is somewhere on Kyushu, with many trying to point to the Yayoi period site of Yoshinogari, though there are plenty of reasons why that particular site is not exactly a good candidate. Then there are various paths taking you to Honshu, and on to Yamato. Those are much more controversial, but the path to at least Na seems mostly agreed on, especially since that was largely the path that individuals would follow for centuries onwards, including missions to and from the Tang dynasty, the Mongols during their attempted invasion, and even the various missions from the Joseon dynasty during the Edo period.

Today, modern transportation, such as the airplane, means that most people just go directly to their destination, but there are still plenty of reasons to visit these locations. It was a lot of fun to sail from place to place and see the next island – or kingdom – emerging on the horizon.

Next episode we will talk about Tsushima and give you an idea of what that island has in store for visitors; especially those with an interest in Japanese history.

Until then, thank you for listening and for all of your support.

If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

Thank you, also, to Ellen for their work editing the podcast.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Kim, P., & Shultz, E. J. (2013). The 'Silla annals' of the 'Samguk Sagi'. Gyeonggi-do: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Kim, P., Shultz, E. J., Kang, H. H. W., & Han'guk Chŏngsin Munhwa Yŏn'guwŏn. (2012). The Koguryo annals of the Samguk sagi. Seongnam-si, Korea: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Jeon, H.-T. (2008). Goguryeo: In search of its culture and history. Seoul: Hollym.

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Shultz, E. (2004). An Introduction to the "Samguk Sagi". Korean Studies, 28, 1-13. Retrieved April 11, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23720180

Iryŏn, ., Ha, T. H., & Mintz, G. K. (2004). Samguk yusa: Legends and history of the three kingdoms of ancient Korea. Seoul: Yonsei University Press.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4