Previous Episodes

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we take a look at the rest of the life of Ōnamuchi. After subduing his “brothers” around the Izumo area and marrying various ladies from all over, he went on to team up with the tiny kami from across the waves, Sukuna Bikona (少彦根).

Now many of the places in this episode can still be visited, today. One of the neat things visiting Japan can be finding some of these traditional locations mentioned all the way back in the 8th century.

The story from the Iyo Fudoki has the two of them meeting at hot spring in Ehime, and tradition claims that as Dōgo Onsen (道後温泉): https://dogo.jp/. Of course, it was a little less built up back then.

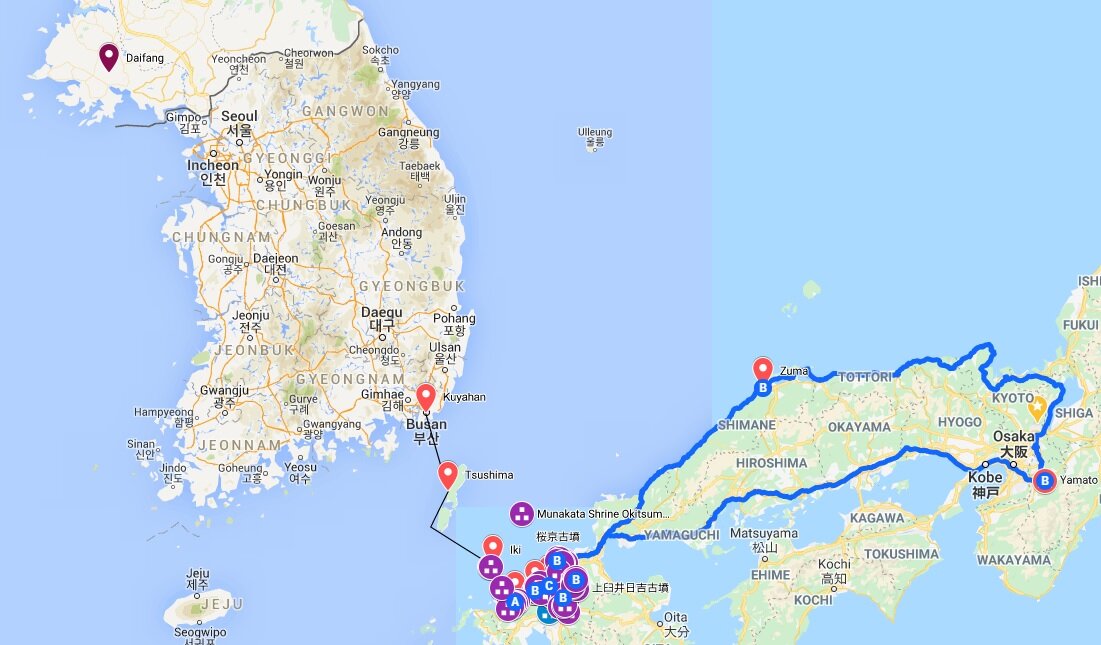

And then there is Mt. Miwa. Ōmiwa shrine (大神神社) is still going strong, and you can visit it in Sakurai: http://oomiwa.or.jp/. Of course, Mt. Miwa is near the Makimuku site from the Yayoi period, as well as near Hashihaka Kofun and many others.

Finally, there is Izumo Taisha, also pronounced Izumo Ōyashiro, (出雲大社): http://www.izumooyashiro.or.jp/. Of course, in this case, the shrine has definitely changed a bit.

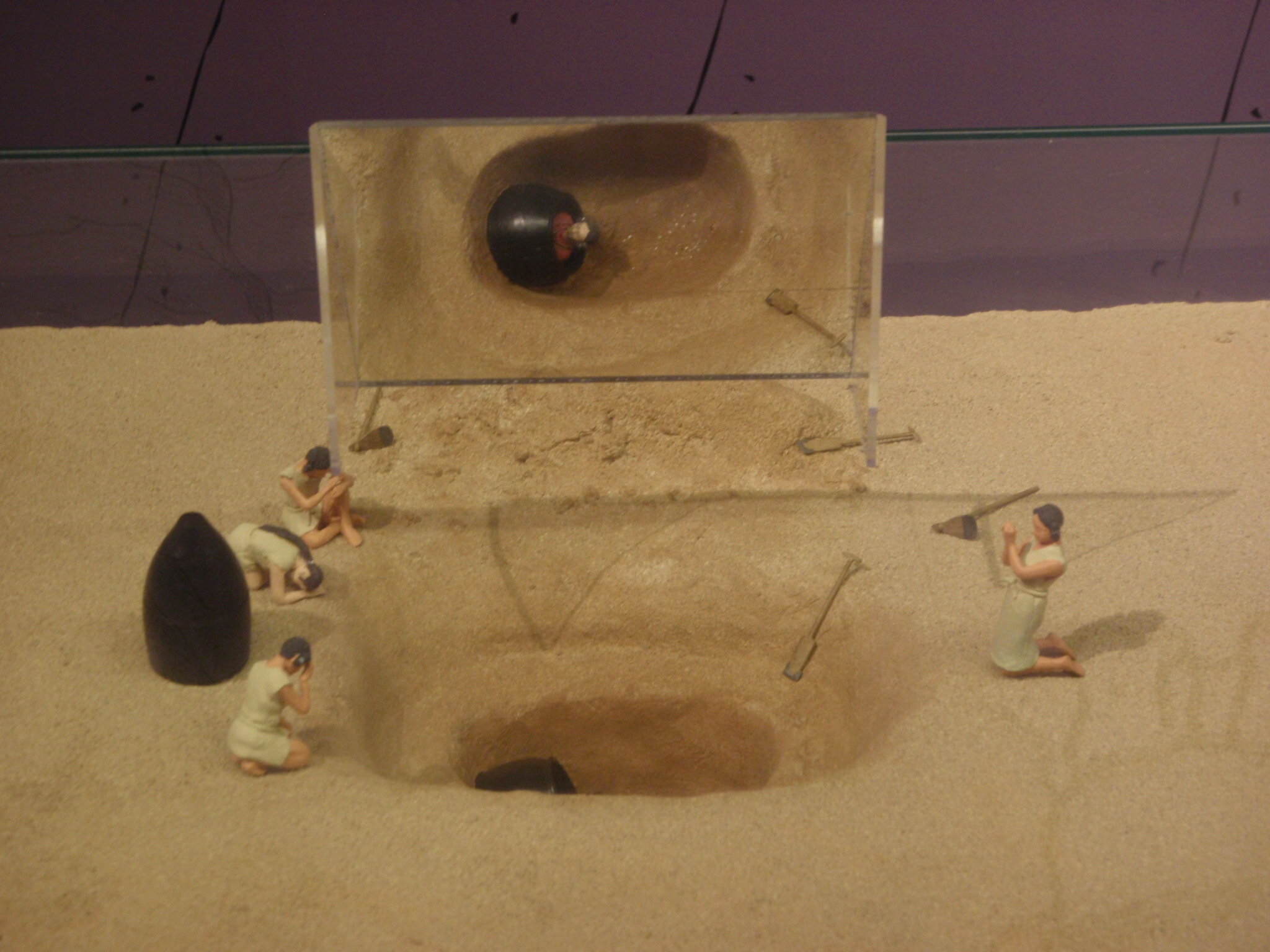

Here are a few photos from the shrine. Unfortunately, when we were last there, the main shrine was under renovation, so I recommend checking it out at the link, above. There are several features of the shrine that make it unique. One was its height—though it used to be much taller than the current building, as can be seen in some of the reconstructions from the Kamakura period and earlier. Another is its orientation. For one thing, the entrance is under gables, rather than the eves. That means that the entrance is in line with the ridge pole, instead of perpendicular to it. This likely developed from the local architecture—it is quite probable that a house, or palace, would have similar features. I doubt it would be quite that high, but they have found Yayoi buildings that had significant pillars, indicating they likely were raised up to some height, such as the “palace” building of the Yoshinogari site, down in Kyūshū.

So we see a lot of importance seemingly placed on Izumo. These early myths are often grouped together as the “Izumo Cycle”. I guess it does make sense to try to keep them together, since regional stories likely had a greater number of connections to other regional stories, and therefore fit together well.

Still, there are other signs of Izumo’s relative independence, many of which we have gone over in previous episodes and blog posts. We will also encounter it in various encounters between Izumo and Yamato. While many of the details are often glossed over, it was clear that there was a sometimes rocky relationship between these polities, even though Yamato and the royal court would seem to win out.

Next episode, we’ll actually go backwards (or forwards? ) to the Yayoi period again and take a look at the growth of the Izumo cultural area in the archaeological record.

For now, thanks for reading and we hope you enjoyed this episode!

References

Torrance, R. (2019). Ōnamochi: The Great God who Created All Under Heaven. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 46(2), 277-318. doi:10.2307/26854516

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Ooms, Herman (2009). Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan: The Tenmu Dynasty, 650-800. ISBN 978-0-8248-3235-3

Bentley, John R (2006). The authenticity of Sendai kuji hongi : a new examination of texts, with a translation and commentary. Brill, Leiden ; Boston

Aoki, Michiko Yamaguchi (1997). Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki with Introduction and Commentaries. Association for Asian Studies. Translations of the Fudoki published online by the Japanese Historical Text Initiative of the University of California at Berkeley at https://jhti.berkeley.edu/NIJL%20gateway.html

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Ellwood, Robert S (1973). The feast of kingship : accession ceremonies in ancient Japan. Sophia University, Tokyo

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1