Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

Who’s Who

Previous Sovereigns

Homuda Wake, aka Ōjin Tennō

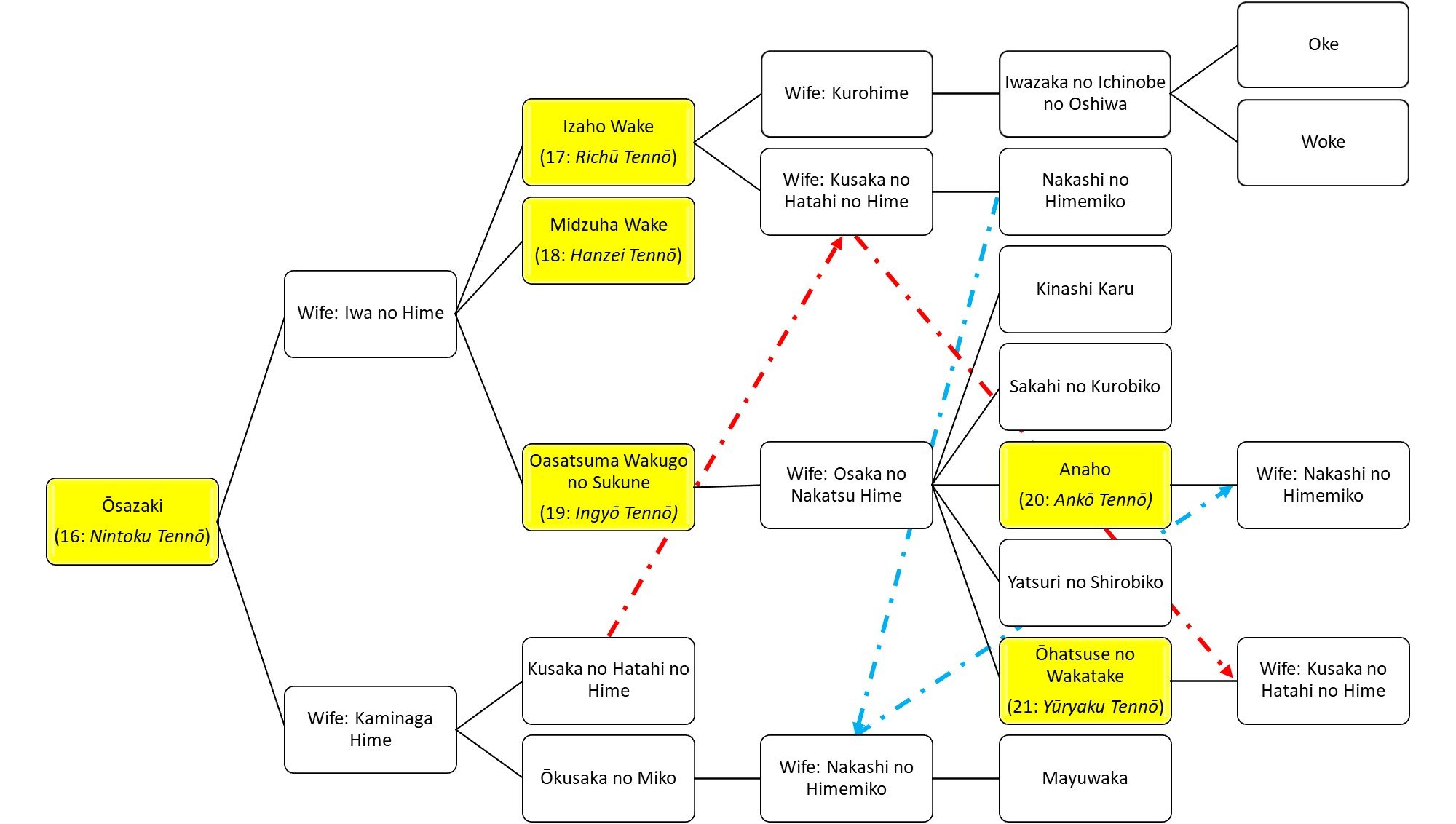

Ōsazaki, aka Nintoku Tennō (Son of Homuda Wake and Naka tsu Hime)

Izaho Wake, aka Richū Tennō (Son of Ōsazaki and Iwa no HIme)

Mizuha Wake, aka Hanzei Tennō (Son of Ōsazaki and Iwa no Hime, and brother to Izaho Wake)

Oasatsuma Wakugo, aka Ingyō Tennō (Son of Ōsazaki and Iwa no Hime, and brother to Izaho Wake and Mizuha Wake)

Sons of Oasatsuma Wakugo and Osaka no Ōnakatsu Hime

Kinashi Karu

Sakahi no Kurobiko [aka 黒彦, the Black Prince]

Anaho

Yatsuri no Shirobiko [aka 白彦, the White Prince]

Ohohatsuse Wakatake

Prince Ōkusaka

Son of Ōsazaki and Kaminaga Hime—mentioned as a possible heir after the death of Mizuha Wake.

Kusaka no Hatahi no Hime

Daughter of Ōsazaki and Kaminaga Hime. Wife to Izaho Wake and, later, Ōhatsuse Wakatake. Mother of Nakashi no Himemiko.

Nakashi no Himemiko

Daughter of Izaho Wake and Kusaka no Hatahi no Hime. Wife of Ōkusaka, with whom she had a son, Mayuwaka. Later married to Anaho.

Important Court Nobles

Ōmahe no Sukune of the Mononobe

Sheltered Prince Kinashi Karu, but eventually convinced him to give up. Later would be made Ōmi.

Ne no Omi

Minister under Anaho, sent to request Hatahi Hime for Ōhatsuse Wakatake

Tsubura no Ōmi

Great Minister (Ōmi) under Anaho, who sheltered princes Mayuwaka and, possibly, Kurobiko

Poetry Between Anaho and Ōmahe no Sukune

When Anaho surround Ōmahe’s residence, it is said that he called out:

Ōmahe / Womahe Sukune ga / Kanato kage / Kakutachi yora ne / Ametachi yamemu

To Ōmahe / Womahe Sukune’s / Metal-gate’s shelter, / Thus let us repair, / And wait till the rain stops

And then, Ōmahe no Sukune replied:

Miyahito no / Ayuhi no ko suzu / Ochiniki to / Miyahito to yomu / Satobito mo yume!

Because the courtier’s / Garter-bell / Has fallen off, / The courtiers make a noise: / Ye country-folks also beware!

Clearly there are a few things that I am not necessarily pulling out of this, but it is full of allusions that no doubt meant something to an 8th century audience.

The Oshiki Crown

The Oshiki Crown is one of the more interesting aspects of this story, in part because it seems to fit with something that we know from the archaeological record. Gold or gilded crowns from Silla and Gaya in the 5th century bear a striking resemblance to similar crowns found in tomb mounds in the archipelago, leading many to conclude that Korean style crowns had become fashionable in the archipelago around this time. See the gallery below for several examples from the Tokyo and Seoul National Museums (photos by author).

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is Episode 57: Chaos and Bloodshed.

Content warning: Along with the violence typical throughout human history, this episode also contains mention of rape and misogyny, as well as suicide.

Last episode we ended with the death of Woasatsuma Wakugo, aka Ingyou Tennou, the last of the sons of Ohosazaki no Mikoto, aka Nintoku Tennou, and Iwa no Hime, daughter of Katsuraki no Sotsuhiko. By now we are reaching the middle of the 5th century, or so it would seem. Now one thing that we didn’t focus on in that last episode was just how prolific Woasatsuma and his wife, Osaka no Ohonakatsu Hime, really were. He certainly didn’t die childless, that’s for sure. In fact, they had at least nine children—five of them male. And so for princes you have Prince Kinashi Karu, Prince Sakahi no Kurobiko, Prince Anaho, Prince Yatsuri no Shirobiko, and Prince Ohohatsuse Wakatake. They also had several daughters, including Nagata no Ohoiratsume, Karu no Ohoiratsume, Tajima no Tachibana no Ohoiratsume, and Sakami.

And no, there won’t be a test. Some of these names will get more air time than others, but I just wanted to give you an idea of the number of individuals here, and, well, you may hear about them later.

By the way, quick side note, did you catch the names Kurobiko and Shirobiko—literally black prince and white prince? I honestly have no idea what’s up with that—are those actual names or is something else going on? After all, we do see names like “Kuro Hime” in the record. At the same time, something seems fishy to me, but whatever. That is what we have to work with.

That said, they are going to be important to the story later, but for now we’ll just leave them here as Chekov’s Princes.

Now, the sovereign Woasatsuma, aka Ingyo Tenno, was dead, but during his life he had, in fact, named an heir. This was Prince Kinashi Karu—or sometimes just Prince Karu.

And all might have gone smoothly—well, alright who am I kidding. I think we are maybe about 50/50 on the named heir actually taking the throne at this point, at least ever since Homuda Wake came to power.

Still, this wasn’t your average succession issue. You see, as Crown Prince, Karu came pre-loaded with a scandal, at least according to the Nihon Shoki. In modern times we might say that he had been cancelled. But what was it that had earned him such approbation? Well it might not be what you expect.

You see, Kinashi Karu, Crown Prince of Yamato, was accused of the most dishonorable activity: Incest.

Alright, now, hear me out. I know this may have many of you furrowing your brows and wondering just what I mean. After all, hasn’t incest been a hallmark of the royal line up to this point? We’ve seen brother and sister marry in the past, and nobody has raised a fuss, not to mention all of the relations between cousins, nephews, nieces, step-relations, etc. As I’ve noted before, the Royal Family Tree is perhaps more of a saguaro than an expansive oak.

So why weren’t those considered incestuous? Well, you see, it all comes down to the definition of lineage in Yamato. Because it wasn’t enough to just have the right father, but matrilineal descent was also key. And so children of the same father and mother were considered true siblings, but as long as you weren’t full siblings—that is, if you had at least one parent different—then it was no longer considered incest by Yamato standards, bringing a whole different meaning to “kissing cousins”.

Now we are told that Kinashi Karu was fair to look upon, and the people apparently used to love him. The problem came about because of his sister, Karu no Ohoiratsume, who was equally as beautiful, and for whom Kinashi Karu had lustful desires, but for a long time he avoided taking any action. However, eventually he failed to control himself, and he met with his sister, secretly uniting with her—that is, they had sex. And, to be honest, it isn’t clear that this was consensual. In fact, the Kujiki actually accuses him of rape. As too often happens, it seems that the chronicle only focuses on the male heir to the royal line, and pays scant attention to anyone else—especially the women. Not to mention, even had she consented, the power dynamics were such that one has to ask: could she have refused if she wanted to?

And you know, he might have gotten away with all of it had he kept their forbidden union secret, but Prince Karu had to shout from the rooftops what they had done, bragging about the event in song. If they’d had Instagram or TikTok I can only imagine what he would have put out there.

Fortunately for him, his father Woasatsuma wasn’t exactly following the latest streams, apparently. In fact, it wasn’t until a year later that something happened to raise his awareness. As the sovereign sat down to his meal, his soup suddenly froze—a curiosity to be sure. A divination was held to determine what was going on, and it was determined that there was a “domestic disorder”, by which they meant some form of incest. On further investigation, someone spilled the beans about Prince Karu and his own sister, Karu no Ohiratsume.

Well, this put the royal family in something of a pickle. Apparently there were no real punishments for the Crown Prince—I suspect that the sovereign could have designated someone else, but for whatever reason, he didn’t. Instead he decided to have his daughter punished, instead—so, both great parenting and a dash of misogyny. Awesome.

And so Princess Karu no Iratsume was banished to the land of Iyo, on the western edge of Shikoku. They figured that as long as the two were separated, nothing more could come of the union.

But that didn’t fix the problem with the members of the court, who knew all too well what had happened. And when Woasatsuma Wakugo died, the court decided that they didn’t exactly want Prince Karu to take the throne. The Nihon Shoki gives as the reason that he was guilty of “debauching a woman”, and says the ministers would not follow him.

As I mentioned earlier, the Kujiki goes further. Though it doesn’t give the details of the Nihon Shoki, it claims that Prince Karu was cruel and accused of rape, which is why nobody would follow him.

Whatever the exact details of the case, the ministers refused to follow him. Rather, they looked to another of Woasatsuma’s progeny—and since he had a proper bench to choose from, they had plenty of options. Of all those heirs available, the ministers chose Prince Anaho, and sided with him.

Kinashi Karu was incensed. He secretly went about raising an army, planning to take his rightful place on the throne by force, but Anaho and his ministers were ready for him, and they prepared themselves for battle as well. Here we get a small glimpse, perhaps, at the changes that were still happening in the 5th century. We are told that the forces of Prince Karu were using an older style of bronze arrowhead, while Prince Anaho’s forces apparently used arrowheads made out of precious iron. Thus, arrows with bronze heads were known as Karu arrows, while arrows with iron heads were known as Anaho arrows, which probably also tells you something about the way this whole thing is going down.

Eventually, Prince Karu realized his forces were not enough, and he fled to the home of Ohomahe no Sukune of the Mononobe. Interestingly, the Kojiki names Mononobe no Ohomahe no Sukune as Oho-omi, or Prime Minister, but the Kujiki, who focuses strongly on the Mononobe lineage, suggests that he did not achieve such rank until a later reign.

Prince Anaho and his forces surrounded Ohomahe no Sukune’s house—possibly amidst a hail storm—and he called out a verse which, along with its response by Ohomahe, is recorded, but abstract enough that I am not sure it is worth getting into here, exactly. I may put that up on the podcast page for anyone who is interested in the exchange.

Anyway, after the exchange—which may have been poetry, or that may simply have been the way that people remembered the story later on—Ohomahe no Sukune begged some time from Prince Anaho and his forces, while he talked with the Crown Prince, Kinashi Karu. They agreed, and Ohomahe returned inside.

We don’t know what was said, but one assumes that Ohomahe got Prince Karu to realize that his case was hopeless. There was no way he was getting out of this alive, and the only question was this: how many people would he take with him?

Whatever Ohomahe actually said, it worked, and Prince Karu, resigned to his fate, ended up taking his own life in the house of Ohomahe no Sukune. When they learned of what he had done, both armies wept at his fate.

Or at least that is one story. The Kojiki, along with what we are told is another record, the “Criminal Register”, which is no longer extant, contends that he gave himself up, and since the court didn’t exactly have a concept of a prison, he was exiled, instead, to the land of Iyo. Presumably, he was then united with Princess Ohoiratsume—assuming that was something she wanted—though there is some confusion on this as it may be that the banishment of Kinashi Karu and of Karu no Ohoiratsume is confused in the Chronicles.

Either way, whether through Karu’s death or banishment, the war was over, and Prince Anaho ascended the throne. The Chroniclers then gave him the name of Ankou Tennou, which is how he is more popularly known, today.

Anaho is said to have dwelt in the Anaho palace at Isonokami. And here is where I suspect Anaho might not actually be the Prince’s given name. You see, most of the early sovereigns are known, particularly in records like the Fudoki, are known by their palace names. So we get the “Sovereign who ruled at the Toyora Palace at Anato”, or the “Sovereign who ruled at the Hishiro Palace at Makimuku”. Some of the legendary sovereigns are simply known by a location, like Iware Biko, but up to this point, I don’t know if I can really think of any other case where the Chronicles claim that the name of the prince and their palace are the same like they are here, especially without giving some other personal name with it, leaving me to wonder just what is going on.

Now after securing the throne and setting up the court, Anaho was left with his mother as Queen Dowager, but no queen of his own. However, before he went looking for love himself, he was approached by his brother, Wakatake no Miko.

At first we are told that Wakatake wished to marry his cousin, the daughter of Midzuha Wake, uncle to Wakatake and Anaho, and previous sovereign himself—the one known as Hanzei Tenno. However, Wakatake was rebuked. His cousin, the princess, said that he was prone to violence, and she did not feel he would appreciate them. Then she claimed that she was neither beautiful enough nor witty enough to be satisfy him.

Undaunted, Prince Wakatake then asked the newly crowned sovereign for the hand of Hatahi no Himemiko, the younger sister of Ohokusaka no Miko. She had previously been married to the sovereign Izaho Wake, or so we are told, and their daughter, Nakashi Hime, apparently married her uncle, Ohokusaka, or at least that’s what it looks like. Yeah, this is all more tangled than a string of lights that’s been

Now, Prince Ohokusaka, you may recall, was the only remaining son of Ohosazaki no Mikoto. He was from a different maternal lineage than the previous three sovereigns since—Izaho, Midzuha, and Woasazuma—and by the rules we’ve been given so far should not have been a contender for the throne, but that does seem to be somewhat in doubt. After all, he seemed to be mentioned after the death of Midzuha Wake as a possibility, at least until Woasazuma was convinced to take up the royal mantle.

And so one imagines Ohokusaka’s sister, Hatahi, would have been a prestigious bride, hence why she had been married to Izaho Wake, previously.

Unlike his brother’s previous marriage request, Anaho no Ohokimi apparently didn’t have any problems with this one – so he sent Ne no Omi to request Hatahi’s hand for his brother Wakatake. Now it turns out that Ohokusaka was ill—quite possibly because he was not only of their father’s generation, but possibly even their oldest uncle. And yet he had kept his sister safe and unmarried, presumably looking for a good match for her, worthy of her royal bloodline.

The Kojiki claims that Ohokusaka made many bows and humbled himself, but both the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki agree that he not only submitted his daughter’s hand for marriage, but also that he sent in a special present to assure the sovereign of his willingness: a jeweled headdress, called in the Chronicles the “Oshiki” crown—possibly indicating that it was made with pressed wood of some kind, though this may have been something else. It may have been a crown in the Korean style, examples of which we see in tomb mound mounds and are known from the 5th century onwards. How it came into Ohokusaka’s possession is not quite clear, but it was definitely something special, despite his own insistence that it was an inconsequential object of no value whatsoever. Even today, this kind of traditional deprecating phrase might accompany gifts in Japan when people describe something as “tsumaranai mono”—literally a “dull” or “boring” thing. And so the crown was sent along with Ne no Omi.

Now, as he was returning to the capital, Ne no Omi coveted the crown, and he decided to steal it, and keep it for himself. And so when he reached the capital he made no mention of it. In fact, he slandered Ohokusaka, and told Anaho that Ohokusaka had refused his orders to send his sister. According to Ne no Omi, Ohokusaka had rebuked the offer, saying “Is my younger sister to be the sleeping mat for an equally ranking family?”

That line, from the Kojiki, only emphasizes the idea that Ohokusaka was probably more legitimate as an heir than the Chronicles let on.

Now the sovereign had no reason not to trust the word of a trusted minister, and so he grew angry at this supposed insolence. He immediately raised an army and sent it after Ohokusaka. They surrounded Ohokusaka’s house and slew him. Ohokusaka had servants of the Hikaka family, the Kishi of Naniwa, in the center of modern Ohosaka, where Homuda Wake and Ohosazaki had their capitals. These servants gathered up his head and legs in hand and wept, for they knew the truth and knew that he had died without committing any crime.

They then said they would not be true servants unless they followed their lord in death, and so they slit their own throats.

The army of the sovereign, Anaho, saw this and wept. It is perhaps the first account we have in the Chronicles of junshi, the act of willingly following a lord in death—a concept that would later take hold amidst the romanticism of warrior culture, to the point that it was specifically outlawed in the Edo period, yet it occasionally still occurred.

With Prince Ohokusaka’s death, the sovereign took Ohokusaka’s wife, his cousin Nakashi Hime, as one of his own consorts, and Ohokusaka’s sister, Kusaka no Hatahi, was finally given to Wakatake no Miko.

Now there is a lot going on here, but let’s briefly step back from some of the blood and death and take a look at what might be going on. Of course the story itself is violent enough, and seems somewhat plausible, except that there had been other examples where someone refused the sovereign and the answer typically wasn’t to raise an army and go kill them. I suspect that there was something deeper at play here.

For one thing, we know that Ohokusaka was a senior male heir to Ohosazaki—or at least he would have been if not for his mother’s supposed position as simply another consort, and not the actual Queen. And yet, even that is unclear—was there actually such a requirement for determining succession? He was, after all, named as one of two potential heirs to the throne on the death of Midzuha Wake, and even the Kojiki’s slander works generally because he would have had to at least conceive of the idea that his lineage was just as grand as Anaho’s—perhaps even more so. After all, this was not yet a period of primogeniture—inheritance did not automatically pass down the paternal line to the eldest son, but rather seems to have been passed along horizontally within the same generation. And so it seems reasonable to assume that Ohokusaka had a viable claim to the throne.

This could also provide another explanation for what was going on. It is quite possible that Ohokusaka's death was part of an active succession dispute, and only later was he declared completely illegitimate. At the very least, this could possibly explain the desire by members of the new generation of rulers for marriage to Ohokusaka’s sister and even his wife, to further strengthen their claims to the throne.

And of course, we shouldn’t forget that for all that the Chronicles make this out to be a dispute kept inside the royal family, there is plenty of speculation that the relationships were not so concrete. There is no guarantee that Anaho was the son of Woasazuma, and if he was, then was Woasazuma actually a son of Ohosazaki, and brother to the previous sovereigns? That all makes some sense, and may be accurate, but there is enough archaeological evidence to suggest that things were much more complex than all of that, and so what we are seeing is an attempt to fit these bits of memory into a story that worked with the prevailing Truth (with a capital T) that Ohoama and his descendants wanted to show.

Regardless, what we have to go on for now are these stories, and this one isn’t quite finished, yet.

I mentioned above that when Anaho’s brother came to him with marriage requests, Anaho didn’t yet have a queen of his own. And so, also as mentioned above, after Ohokusaka’s death, and after Wakatake was betrothed to Kusaka no Hatahi, the sovereign also decided it was time to take a wife – and he took Ohokusaka’s wife, Nakashi Hime, as his own. Of course, she had been married previously, and not only that, but she and Ohokusaka had a son: Prince Mayowa. And when Anaho took Nakashi Hime for his wife, he took Mayowa and had him raised in the palace. The Kujiki mentions that he was “not punished”—something of an odd phrasing, possibly referring to the generous treatment he had, or possibly talking about the fact that he was allowed to live. Either way, he was allowed free range of the palace.

Now we are told that Mayowa was just a boy, maybe as young as 6 or 7 years old, though possibly older given some of what we learn. And it seems he was not even fully aware of the circumstances behind his father’s death. And that worried Anaho. As time went on, he started to worry more and more about just what would happen if Mayowa were to discover the truth.

One day, Anaho and the court had gone up into the mountain palace to enjoy the local hot springs. He was there with his wife, Nakashi hime. In the Kojiki they say he was on the royal bed, taking his mid-day siesta, and in the Nihon Shoki he was up in a tower of the palace looking out at the beauty of nature while ordering up sake for a banquet. In either case, he decided to confide in his wife the worries he had for her son, Mayowa. More and more he worried that Mayowa would grow up and learn that Anaho had been the one to have ordered his father, Ohokusaka, killed. If that were to happen, would not some evil start to form in his heart?

As he said this, no doubt believing it to be in confidence, he did not realize that Prince Mayowa was actually quite near. He had gone underneath the palace, which must have been built up off the ground, and he was playing by the pillars, and he heard Anaho’s confession. That night, when the sovereign was fast asleep, the young prince took the sword from the sovereign’s side and slit Anaho’s throat with it. He then ran away from the palace.

Now to quickly recap where we are—and we are only halfway through and I warn you that there is plenty of blood to come. So first, we had the Crown Prince Karu, who was rebuked by the court, who backed Prince Anaho. Anaho defeated Prince Karu. Later—possibly because of a misunderstanding—Anaho defeated and killed Prince Ohokusaka, the last of his father’s generation of potential heirs. But then, Prince Mayowa, Ohokusaka’s own son, had killed Anaho, to get revenge or his own father’s death.

Are you with me so far?

Word must have spread quickly about the sovereign’s death, and one of the first to hear of it was Wakatake, younger brother to Anaho, and the guy who had requested the hand of Kusaka no Hatahi and thus possibly kicked off the whole bloodbath with Ohokusaka. It’s actually not the first time we’ve heard of Wakatake, either: before that he was the one who had punished and tortured the Silla envoys when he thought they had been misusing the women of the court. Now he was fired up, and determined to find justice for his older brother. Or at least, that’s what he said—one can hardly doubt that he must have realized that there was suddenly a power vacuum, one he would have to work quickly to exploit.

And so Wakatake put on his armor and girded his sword, claiming that he was worried that his elder brothers might try to start something—though I highly suspect that if he felt this way, it was probably more than a little bit of psychological projection.

What happened next is a little different in the different Chronicles. The Kojiki tells it with relative simplicity: Wakatake went to the house of his older brother, Kurobiko, the Black Prince, and he asked what was to be done about Mayowa, who had just killed their father. Kurobiko seemed unphased and indifferent, however, which merely enraged Wakatake, who scolded him, saying: “How can you be so lazy on hearing that the sovereign, your brother as well as mine, has been killed?”

Then in a fit of rage, he grasped his older brother by the collar, pulled out his sword, and killed him.

He then stormed off to the house of his other brother, Shirobiko, the White Prince, but his other brother was likewise unconcerned, which just made Wakatake more angry. He had Shirobiko placed in a pit on the Owari fields and buried upright. When Shirohiko was buried up to his waist, both of his eyes popped out of his head, and he died.

And might we pause for a moment to notice what was going on? According to the Kojiki, Wakatake was upset about his brother’s death and so he… killed his brothers? Yeah, that doesn’t exactly add up. Not that he killed them, but his supposed reasoning.

In the Nihon Shoki it is told a little bit differently. There, Wakatake approached Shirobiko first, bringing a large army. He started interrogating his brother, but Shirobiko knew right away that Wakatake was just looking for some kind of an excuse, and so Shirobiko remained silent and refused to say anything. Finally, Wakatake had had enough, and in this version it is Shirobiko whom he ran through with his sword. He then went on to Kurobiko, where the same thing happened but, for whatever reason, he didn’t kill Kurobiko. Instead he traveled on to Mayowa and interrogated him. Mayowa claimed that he never wanted the throne, he just wanted revenge for the death of his father, Prince Ohokusaka.

While Wakatake was apparently deciding what he should do with the two of them, Kurobiko passed a message to Mayowa, and they both ran away together, taking shelter with Tsubura no Oho-omi—who, by his title, appears to have been the Prime Minister, as it were, of his day.

Here is where the narratives come together, mostly. In the Kojiki, you see, Mayowa had already run off to Tsubura no Ohoomi.

Wakatake raised an army and surrounded the house of Tsubura no Ohomi. He sent in a messenger to talk to Tsubura no Ohomi and to ask him to turn over the Princes he was protecting. Tsubura no Ohomi apologized, however, as he could not comply. As he explained, in antiquity there were plenty of times that an Omi or a Muraji might take shelter in the house of a prince, but a royal prince hiding in the house of a vassal, well wasn’t that unheard of? And he was mostly correct, at least if you don’t count Prince Karu hiding in the house of Omahe no Sukune, but hey, what’s a plothole or two between friends?

In this case, though, Tsubura no Ohomi was not Omahe no Sukune. Where Omahe had given up Prince Karu, Tsubura no Ohomi was not about to give up the princes under his care. Instead, he came out and tried to bargain.

He offered up his own daughter, Kara Hime, as well as the granaries of Kadzuraki. But he could not give up the Princes. The Nihon Shoki places in his mouth the words of no other than the venerable Confucius himself as Tsubura no Ohomi said that “The will of even a common man cannot be taken from him.”

Wakatake took the tribute, but he was not appeased. He had his men burn Tsubura no Ohoomi’s home to the ground, along with everyone inside, including the Minister and both of the Princes. As it was still burning, apparently one of Kurobiko’s servants, Nihe no Sukune, the Muraji of the Sakahibe, ran in and took the Prince’s still burning corpse in his arms, and so also burnt to death. Later, the Sakahibe would attempt to sort out the bones, but they could not, and they were all deposited together in a single coffin and buried together.

And with that, Wakatake suddenly found himself the only remaining heir to the throne—funny that.

Or, well, at least, he was the only heir from Woasazuma’s line. There was at least one more prince we are told. Ichinobe no Oshiwa no Miko of Iwazaka was the son of Izaho Wake and Kurohime. When his father had passed away, the throne went to his uncle, Midzuha Wake, perhaps because his mother was not considered a queen, but I figure it is more likely that succession at this time was more likely to run to the next head of the household—typically from brother to brother—before it went to the next generation. It could also have just been the case that Ichinobe no Oshiwa was too young at the time of his father’s death.

Whatever the reason, apparently Anaho, who had no children of his own, had named Ichinobe no Oshiwa as the Crown Prince, should anything happen to him. So that meant that technically, for all of the blood he had spilt, it was almost meaningless, since none of the other brothers were actually in line for the throne. Technically, for all that his brother, Anaho, had succeeded their father, it looked like the line was reverting back to a previous branch of the family tree.

Of course, this was a bit of a fly in Wakatake’s ointment. He had successfully disposed of most of his rivals—also known as “family”—but there was one more left. And so he came up with a plan. He sent a servant to invite Ichinobe no Oshiwa on a hunting excursion to the land of Afumi, where a local lord had told him the deer were particularly plentiful.

Now I don’t know about you, but if I was the next in line to the throne, and my ambitious cousin had just killed all of his family and potential rivals, before then inviting me to do a bit of hunting… well, I like to think that I might have had an inkling something was up. But perhaps Wakatake had come up with a really good explanation for all of that, or perhaps Ichinobe just hadn’t received word of the fratricide that had recently taken place. I also have to wonder whether or not Ichinobe had actually taken the throne, though the Chronicles don’t mention anything about that. But if he was the sovereign, I supposed it could be entirely possible that Wakatake had pledged his loyalty to him in some way.

Whatever the reason, Ichinobe trusted his cousin, and together they went out on the moors, hunting for deer.

As they rose to go hunting, Ichinobe no Oshiwa rose first and called for his cousin. He then headed out on the moors ahead. Wakatake, on the other hand, girded himself in armor under his clothing—not exactly the kind of get up one usually dons when going hunting, unless you are, perhaps, hunting the Most Dangerous Game.

Sure enough, Wakatake spurred his horse onwards and eventually overtook Ichinobe no Oshiwa, and as soon as they were side by side, Wakatake drew back his bow and shot his cousin. Then, in a particularly gruesome display, he had the body chopped up and added to the feedbuckets of the horses—I guess they didn’t have any pigs handy, yet. Whatever remained was unceremoniously buried in the ground, without even a small mound to mark the would-be-sovereign’s memory.

When word got back to Ichinobe’s house of what had happened, his two sons, Oke and Woke—yes, those are their names as given—fled, fearing for their lives. They ended up in Harima and hid as servants, so that they would not be found.

And with that, the way was clear. Ohohatsuse no Wakatake had no more rivals to contend with. In a pageant of blood, he had wiped clear any opposition, and as such we are told that he ascended the throne. Later Chroniclers would name him Yuuryaku Tennou, and his cruelty would be legendary.

But that is a legend that we will relate at a later date. In addition, next episode, I’d really like to get into some of the interesting evidence we have that may be direct references to Wakatake no Ohokimi in Continental sources as well as in archaeological evidence found in the archipelago itself—evidence that many believe refers directly to this sovereign by name. All of that we will discuss in our next episode.

And, so, until then, thank you for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate through our KoFi site, kofi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the link over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com. We would love to hear from you and your ideas.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Kawagoe, Aileen (2009). “Uji clans, titles and the organization of production and trade”. Heritage of Japan. https://heritageofjapan.wordpress.com/following-the-trail-of-tumuli/rebellion-in-kyushu-and-the-rise-of-royal-estates/uji-clans-titles-and-the-organization-of-production-and-trade/. Retrieved 1/11/2021.

Confucius, ., & Legge, J. (2008). The Analects of Confucius. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide Library.

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1