Previous Episodes

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we look at the first year of the reign of Ōama, aka Temmu Tennō, who formally ascended the throne in 673. We see feasts, and ceremonies associated with his ascension, as well entreaties to both Buddhism and Kami worship. We talk about the various missions from across the seas, and we touch on the numerous death notices in this reign—where there is mention of the death of one or more of Ōama’s supporters from the Jinshin War. We also talk about the rank that he handed out.

The end of the year we see the Niinamesai (新嘗祭) turned into the Daijōsai (大嘗祭). This tradition would continue through the centuries, and continues to be celebrated even today upon the ascension of a new emperor to the throne. For more on the Daijōsai, you may want to check out Robert S. Ellwood’s monograph: The Feast of Kingship: Accession Ceremonies in Ancient Japan.

Ranks of 664

These were the ranks that were created in 664. For older rank charts, check out Episode 111.

Dai-shiki (大織 - Greater Woven Stuff)

Shou-shiki (小織 - Lesser Woven Stuff)

Dai-hou (大縫 - Greater Sewing)

Shou-hou (小縫 - Lesser Sewing)

Dai-shi (大紫 - Greater Purple)

Shou-shi (小紫 - Lesser Purple)

Upper Daikin (大錦上 - Greater Brocade, Upper)

Middle Daikin (大錦中 - Greater Brocade, Middle

Lower Daikin (大錦下 - Greater Brocade, Lower)

Upper Shoukin (小錦上 - Lesser Brocade, Upper)

Middle Shoukin (小錦中 - Lesser Brocade, Middle)

Lower Shoukin (小錦下 - Lesser Brocade, Lower)

Upper Daisen (大山上 - Greater Mountain, Upper)

Middle Daisen (大山中 - Greater Mountain, Middle)

Lower Daisen (大山下 - Greater Mountain, Lower)

Upper Shousen (小山上 - Lesser Mountain, Upper)

Middle Shousen (小山中 - Lesser Mountain, Middle)

Lower Shousen (小山下 - Lesser Mountain, Lower)

Upper Daiotsu (大乙上 - Greater Tiger [OR Kingfisher], Upper)

Middle Daiotsu (大乙中 - Greater Tiger, Middle)

Lower Daiotsu (大乙下 - Greater Tiger, Lower)

Upper Shouotsu (小乙上 - Lesser Tiger, Upper)

Middle Shouotsu (小乙中 - Greater Tiger, Middle)

Lower Shouotsu (小乙下 - Lesser Tiger, Lower)

Daiken (大建 - Greater Building)

Shouken (小建 - Lesser Building)

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is episode 135: Year One

The officials of the Ministry of Kami Affairs bustled to and fro as they prepared the ritual grounds and the temporary buildings. They were carefully erecting the structures, which would only be used for a single festival, and then torn down, but this would be an important festival. It was the harvest festival, the Niiname-sai, the festival of the first-fruits. Rice, from the regions of Tamba and Harima, specifically chosen through divination, would be offered to his majesty along with the kami who had blessed the land. But this time, there was more.

After all, this was the first harvest festival of a new reign, and they had orders to make it special. The ascension ceremony had been held earlier in the year, but in some ways that was just a prelude. There had been various rituals and ceremonies throughout the year emphasizing that this year was special—even foreign lands were sending envoys to congratulate him on the event. But this wasn’t for them. This was the sovereign taking part, for the first time, in one of the most important ceremonies of the year. After all, the feast of first-fruits was the culmination of all that the kami had done, and it emphasized the sovereign’s role as both a descendant of heaven and as the preeminent intercessor with the divine spirits of the land.

And so they knew, that everything had to be bigger, with even more pomp and circumstance than normal. This wouldn’t just be about the new rice. This would be a grand ceremony, one that only happened once in a generation, and yet which would echo through the centuries. As the annual harvest festival, it was an ancient tradition. But as something new—as the Daijosai—it was something else all together.

And it would have to be perfect!

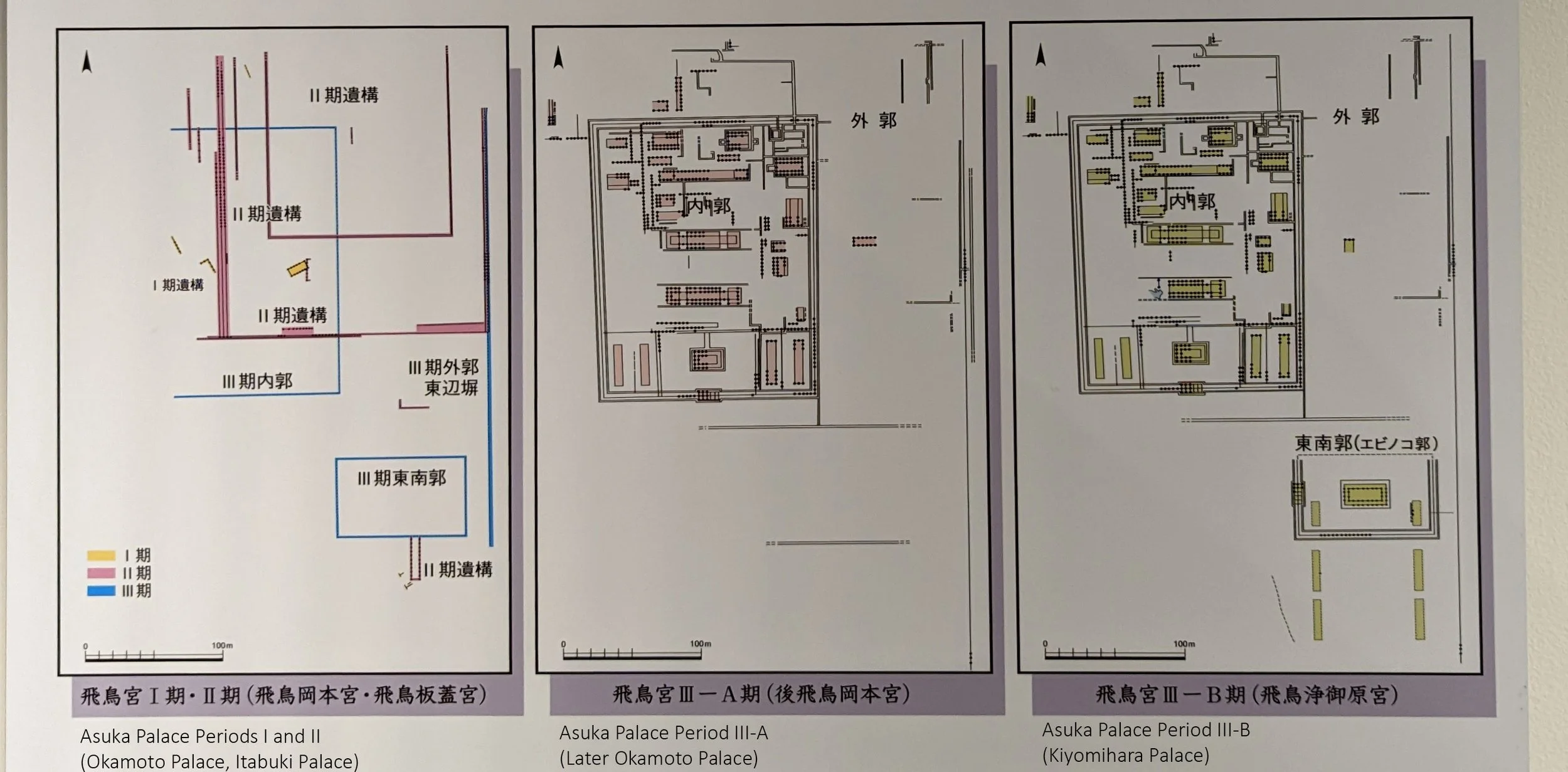

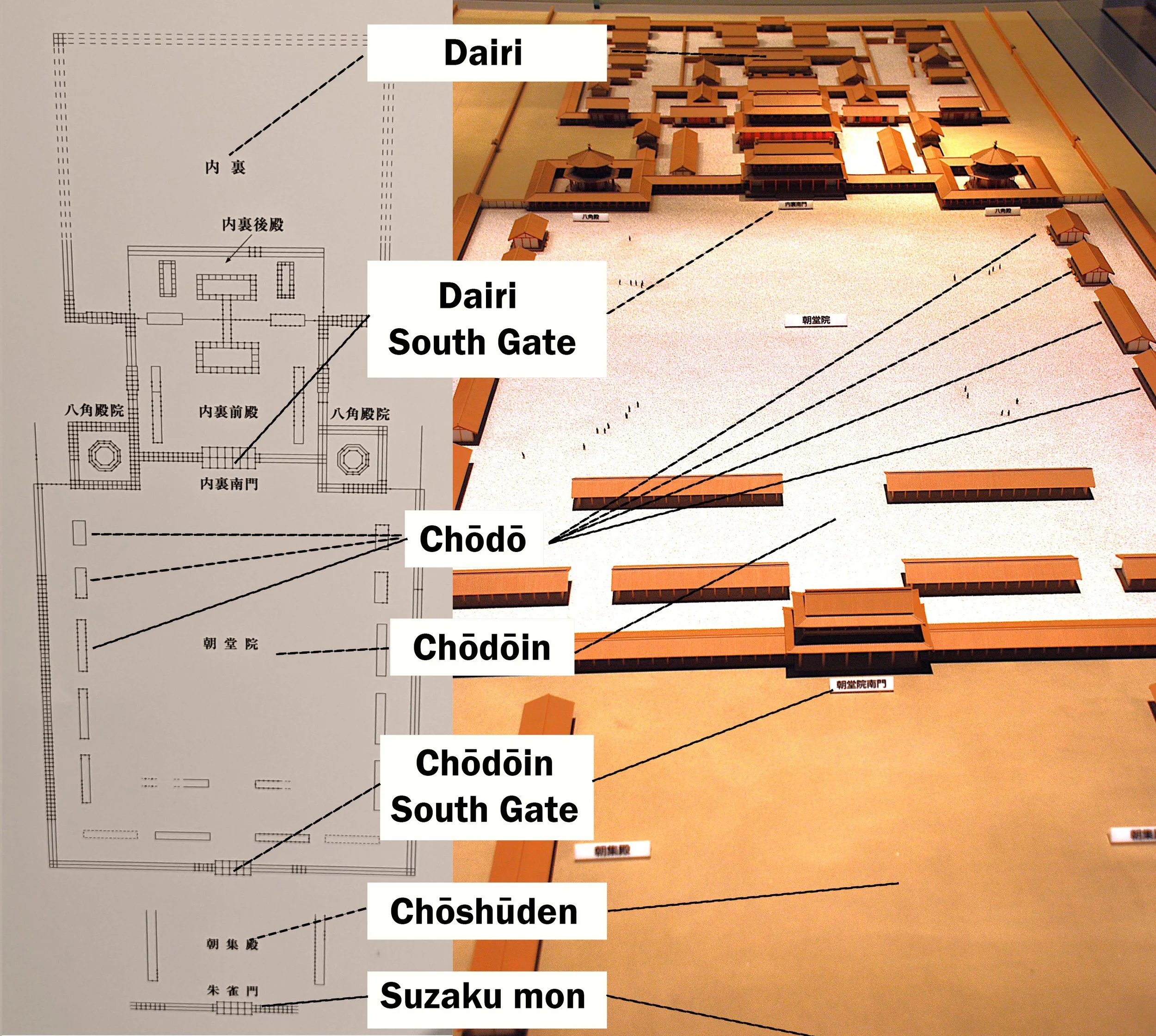

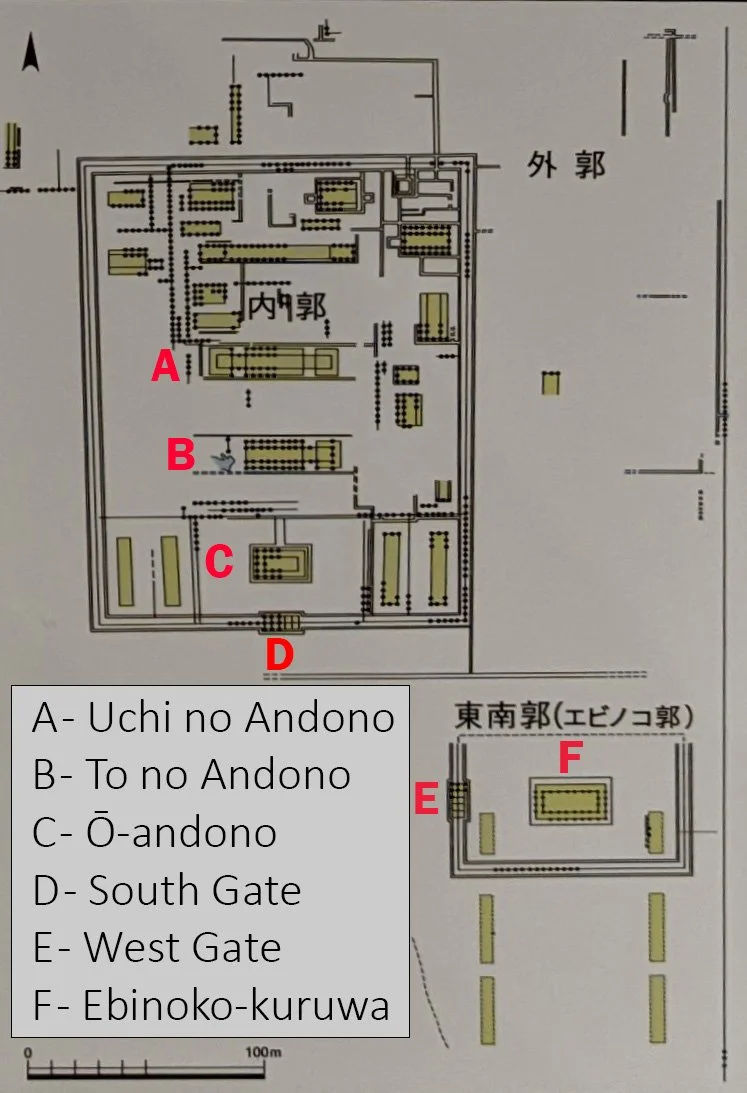

Last episode we talked about the Kiyomihara palace and a little bit about what it was like in the court of Ohoama, aka Temmu Tennou. After defeating the Afumi court supporting his nephew, Ohotomo, in 672, Ohoama had taken control of the government. He moved back to Asuka, and into the refurbished Okamoto palace, building a southern exclave known to us today as the Ebinoko enclosure, which held one large building, which may have been a residence or a ceremonial structure—possibly the first “Daigokuden” or ceremonial hall.

Ohoama’s court built on the ideas that his brother, Naka no Oe, aka Tenji Tennou, had put forth since the Taika era. This was a continuation of the form of government known as the Ritsuryo system, or Ritsuryo-sei, literally a government of laws and punishments, and Ohoama had taken the reins. He seems to have taken a much more direct approach to governance compared to some of his predecessors. For instance, the role of the ministerial families was reduced, with Ohoama or various princes—actual or invented relatives of the throne—taking a much more prominent role. He also expanded access to the central government to those outside of the the Home Provinces. After all, it was the traditional ministerial families—the Soga, the Nakatomi, and even the Kose—who had been part of the Afumi government that he had just defeated. Meanwhile, much of his military support had come from the Eastern provinces, though with prominent indications of support from Kibi and Tsukushi as well.

This episode we are going to get back to the events documented in the Chronicles, looking just at the first year of Ohoama’s reign. Well, technically it was the second year, with 672 being the first, but this is the first year in which he formally sat on the throne. There’s plenty going on in this year to fill a whole episode: it was the year of Ohoama’s formal ascension, and there were numerous festivals, ceremonies, and other activities that seem to be directly related to a fresh, new start. We will also look at the custom of handing out posthumous ranks, particularly to those who supported Ohoama during the Jinshin no Ran, and how that relates to the various ranks and titles used in Ohoama’s court. We have envoys from three different countries—Tamna, Silla, and Goguryeo—and their interactions with the Dazaifu in Tsukushi. Finally, we have the first Daijosai, one of the most important ceremonies in any reign.

And so, let’s get into it.

The year 673 started with a banquet for various princes and ministers, and on the 27th day of the 2nd month, Ohoama formally assumed the throne at what would come to be known as Kiyomihara Palace. Uno, his consort, who had traveled with him through the mountains from Yoshino to Ise, was made his queen, and their son, Royal Prince Kusakabe, was named Crown Prince. Two days later they held a ceremony to convey cap-ranks on those deemed worthy.

We are then told that on the 17th day of the following month, word came from the governor of Bingo, the far western side of ancient Kibi, today the eastern part of modern Hiroshima. They had caught a white pheasant in Kameshi and sent it as tribute. White or albino animals were seen as particularly auspicious signs, and no doubt it was taken as an omen of good fortune for the reign. In response, the forced labor from Bingo, which households were required to supply to the State, was remitted. There was also a general amnesty granted throughout the land.

That same month we are also told that scribes were brought in to Kawaradera to copy the Issaiko—aka the Tripitaka, or the entirety of the Buddhist canon. That would include hundreds of scrolls. This clearly seems to be an act of Buddhist merit-making: by copying out the scrolls you make merit, which translates to good karma. That would be another auspicious start to the reign, and we see frequently that rulers would fund sutra copying—or sutra recitations—as well as temples, statues, bells and all other such things to earn Buddhist merit. As the ruler, this merit didn’t just accrue to you, but to the entire state, presumably bringing good fortune and helping to avert disaster.

However, it wasn’t just the Law of the Buddha that Ohoama was appealing to. In the following entry, on the14th day of the 4th month, we are told that Princess Ohoki was preparing herself at the saigu, or abstinence palace, in Hatsuse—known as Hase, today, east of modern Sakurai, along the Yonabari river, on the road to Uda. Ohoki was the sister of Prince Ohotsu. Her mother was Ohota, the Queen’s elder sister, making her a grandchild of Naka no Ohoye as well as the daughter of Ohoama.

Princess Ohoki’s time at the abstinence palace was so that she could purify herself. This was all to get her ready to head to Ise, to approach none other than the sun goddess, Amaterasu Ohokami.

With all of these events, we see the full panoply of ritual and ceremony on display. The formal, legal ceremonies of ascension and granting of rank. The declaration of auspicious omens for the reign. There is the making of Buddhist merit, but also the worship of the kami of the archipelago. This is not an either-or situation. We are seeing in the first half of this first year the fusion of all of these different elements into something that may not even be all that sensational to those of us, today. After all, anyone who goes to Japan is likely well-accustomed to the way that both Buddhist and Shinto institutions can both play a large part in people’s lives. While some people may be more drawn to one than the other, for most they are complimentary.

That isn’t how it had to be. For a time, it was possible that Buddhism would displace local kami worship altogether. This was the core of the backlash that we saw from groups like the Nakatomi, whose role in kami-focused ceremonies was threatened by the new religion. Indeed, for a while now it seems like mention of the kami has taken a backseat to Buddhist temples and ceremonies in the Chronicles. Likewise, as a foreign religion, Buddhism could have also fallen out of favor. It was not fore-ordained that it would come to have a permanent place on the archipelago.

This tension between local kami worship—later called Shinto, the Way of the Kami—and Buddhist teachings would vary throughout Japanese history, with one sometimes seen as more prestigious or more natural than the other, but neither one would fully eclipse the other.

One could say that was in part due to the role that Amaterasu and kami worship played in the court ceremonies. However, even there indigenous practices were not necessarily safe. The court could have just as easily imported Confucian rituals, and replaced the spiritual connection between the sovereign and the kami with the continental style Mandate of Heaven.

And thus, the choices that were being made at this time would have huge implications for the Japanese state for centuries to come.

I should note that it is unlikely that this spontaneously arose amongst the upper class and the leadership. I doubt this was just Ohoama’s strategy to give himself multiple levers of power—though I’m not saying he wasn’t thinking about that either. But the only way that these levers existed was through their continued life in the culture and the people of the time. If the people didn’t believe in Buddhist merit, or that the kami influenced their lives, then neither would have given them much sway. It was the fact that these were a part of the cultural imaginary of the state, and how people imagined themselves and their surroundings, that they were effective tools for Ohoama and his government.

And so it seems that Ohoama’s first year is off to a smashing success. By the fifth month he is already issuing edicts—specifically on the structure of the state, which we discussed some last episode.

But the high could not be maintained indefinitely. And on the 29th day of the 5th month we have what we might consider our first negative entry, when Sakamoto no Takara no Omi passed away.

You may remember Sakamoto, but I wouldn’t blame you if you didn’t. He was the commander in the Nara Basin, under general Wofukei, who took 300 troops to Tatsuta. From there he advanced to the Hiraishi plain and up to the top of Mt. Takayasu, to confront the Afumi forces that had taken the castle. They fled, and Takara and his men overnighted at the castle. The next day they tried to intercept Afumi troops advancing from the Kawachi plain, but they were forced to fall back to a defensive position. We covered that in Episode 131 with the rest of the campaign in the Nara Basin.

Takara’s death is the first of many entries—I count roughly 21 through this and the following reign—which, for the most part, are all similarly worded. Sakamoto no Takara no Omi, of Upper Daikin rank, died. He was posthumously granted the rank of Shoushi for service in the Year of Mizu-no-e Saru, aka Jinshin. We are told the individual, their rank at the time of their death, and then a note about a posthumous grant of rank.

Upper Daikin was already about the 7th rank from the top in the system of 664, and Shoushi would be the 6th rank, and one of the “ministerial” ranks. This is out of 26, total. “Kin” itself was the fourth of about 7 categories, and the last category that was split into six sub-ranks, with greater and lesser (Daikin and Shokin), each of which was further divided into Upper, Middle, and Lower ranks. There’s a lot to go into, in fact a little too much for this episode, so for more on the ranks in use at the start of the reign, check out our blogpost for this episode.

The giving of posthumous rank is mostly just an honorific. After all, the individual is now deceased, so it isn’t as if they would be drawing more of a stipend, though their new ranks may have influenced their funerary rites and similar things.

As I said, on a quick scan of the text, I counted 21 of these entries, though there may be a few more with slightly different phrasing or circumstances. Some of them were quite notable in the record, while others may have only had a mention here or there. That they are mentioned, though, likely speaks to the importance of that connection to such a momentous year. The Nihon Shoki is thought to have been started around the time of Ohoama or his successor, along with the Kojiki, and so it would have been important to people of the time to remind everyone that their ancestors had been the ones who helped with that momentous event. It really isn’t that much different from those who proudly trace their lineage back to heroes of, say, the American Revolution, though it likely held even more sway being closer to the actual events.

After the death of Sakamoto no Takara, we get another death announcement. This is of someone that Aston translates as “Satek Syomyeong” of Baekje, of Lower Daikin rank. We aren’t given much else about him, but we are told that Ohoama was shocked. He granted Syomyeong the posthumous rank of “Outer Shoushi”, per Aston’s translation. He also posthumously named him as Prime Minister, or Desapyong, of Baekje.

There are a few clues about who this might be, but very little to go on. He is mentioned in 671, during the reign of Naka no Oe, when he received the rank of Upper Daikin along with Minister—or Sapyong—Yo Jasin. It is also said in the interlinear text that he was the Vice Minister of the Ministry of Judgment—the Houkan no Taifu. The Ministry of Judgment—the Houkan or perhaps the Nori no Tsukasa—is thought to have been the progenitor of the later Shikibu, the Ministry of Ceremony. One of the major roles it played was in the selection of candidates for rank, position, and promotion.

We are also told that in the year 660, in the reign of Takara Hime, one of the nobles captured in the Tang invasion of Baekje was “Desapyong Satek”, so perhaps this Syomyeong was a descendant or relative of the previous prime minister, who fled to Yamato with other refugees. We also have another record from 671 of a Satek Sondeung and his companions accompanying the Tang envoy Guo Yacun. So it would seem that the Sathek family was certainly notable

The name “Satek” shows up once more, though Aston then translates it as “Sataku”, like a monk or scholar’s name. “Sataku” would be the Japanese on’yomi pronunciation of the same characters, so perhaps another relative.

What we can take away from all of this is that the Baekje refugee community is still a thing in Yamato. This Satek Seomyeong has court rank—Upper Daikin rank, just like Sakamoto, in the previous entry. And we know that he had an official position at court—not just in the Baekje court in exile. We’ll see more on this as the community is further integrated into the rest of Society, such that there would no longer be a Baekje community, but families would continue to trace their lineages back to Baekje families, often with pride.

The other odd thing here is the character “outer” or “outside” before “Shoushi”. Aston translates it as part of the rank, and we see it show up a total of four times in some variation of “Outer Lesser X rank”. Mostly it is as here, Outer Lesser Purple. Later we would see a distinction of “outer” and “inner” ranks, which this may be a version of. Depending on one’s family lineage would denote whether one received an “outer” or “inner” rank, and so it may be that since Satek Syomyeong was from the Baekje community, it was more appropriate for him to have an “outside” rank.

“Outer” rank would also be given to Murakuni no Muraji no Woyori, the general who had led the campaign to Afumi, taking the Seta bridge. He was also posthumously given the rank of “Outer Shoushi” upon his death in 676. Murakuni no Woyori is the only person of that surname mentioned around this time, so perhaps he wasn’t from one of the “core” families of the Yamato court, despite the service he had rendered. We also have at least one other noble of Baekje who is likewise granted an ”outer” rank.

On the other side there are those like Ohomiwa no Makamuta no Kobito no Kimi, who was posthumously granted the rank of “Inner” Shoushi. Here I would note that Ohomiwa certainly seems to suggest an origin in the Nara Basin, in the heartland of Yamato.

The terms “Inner” and “Outer” are only used on occasion, however, and not consistently in all cases. This could just be because of the records that the scribes were working off of at the time. It is hard to say, exactly.

All of these entries about posthumous ranks being granted tend to refer to cap ranks, those applying to members of various Uji, the clans that had been created to help organize the pre-Ritsuryo state. The Uji and their members played important roles in the court and the nation, both as ministers and lower functionaries. But I also want to mention another important component of Ohoama’s court, the members of the princely class, many of whom also actively contributed to the functioning of the state.

Among this class are those that Aston refers to as “Princes of the Blood”, or “Shinnou”. These include the royal princes, sons of Ohoama who were in line for the throne, but also any of his brothers and sisters. Then there were the “miko”, like Prince Kurikuma, who had been the Viceroy in Tsukushi, denying troops to the Afumi court. Those princes claimed some lineal descent from a sovereign, but they were not directly related to the reigning sovereign. In fact, it isn’t clear, today, if they were even indirectly related to the reigning sovereign, other than through the fact that the elites of the archipelago had likely been forming marriage alliances with one another for centuries, so who knows. And maybe they made their claims back to a heavenly descendant, like Nigi Hayahi. Either way, they were the ones with claims—legitimate or otherwise—to royal blood.

Notably, the Princes did not belong to any of the Uji, , and they didn’t have kabane, either—no “Omi”, “Muraji”, “Atahe”, et cetera. They did, at least from this reign forward, have rank. But it was separate and different from the rank of the Uji members. Members of the various Uji were referred to with cap rank, but the Princely ranks were just numbered—in the Nihon Shoki we see mention of princes of the 2nd through 5th ranks—though presumably there was also a “first” rank. It is not entirely clear when this princely rank system was put into place, but it was probably as they were moving all of the land, and thus the taxes, to the state. Therefore the court would have needed to know what kind of stipend each prince was to receive—a stipend based on their rank. These ranks, as with later numbered ranks, appear to have been given in ascending order, like medals in a tournament: first rank, second rank, third rank, etc. with fifth rank being the lowest of the Princely ranks.

Many of these Princes also held formal positions in the government. We saw this in Naka no Oe’s reign with Prince Kurikuma taking the Viceroy-ship of Tsukushi, but during Ohoama’s reign we see it even more.

Beneath the Princes were the various Ministers and Public Functionaries—the Officers of the court, from the lowest page to the highest minister. They were members of the elite noble families, for the most part, or else they claimed descent from the elite families of the continent. Either way they were part of what we would no doubt call the Nobility. Their cap-rank system, mentioned earlier, was separate from that used by the Princes.

And, then at the bottom, supporting this structure, were the common people. Like the princes, they did not necessarily have a surname, and they didn’t really figure into the formal rank system. They certainly weren’t considered members of the titled class, and often don’t even show up in the record. And yet we should not forget that they were no doubt the most numerous and diverse group for the majority of Japanese history. Our sources, however, have a much more narrow focus.

There is one more class of people to mention here, and that is the evolving priestly class. Those who took Buddhist orders and became Buddhist monks were technically placed outside of the social system, though that did not entirely negate their connections to the outsided world. We see, for example, how Ohoama, even in taking orders, still had servants and others to wait on him. However, they were at least theoretically outside of the social hierarchy, and could achieve standing within the Buddhist community through their studies of Buddhist scripture. They had their own hierarchy, which was tied in to the State through particular Buddhist officers appointed by the government, but otherwise the various temples seem to have been largely in charge of their own affairs.

But anyway, let’s get back to the Chronicles. Following closely on the heels of Satek Syomyeong’s passing, two days later, we have another entry, this one much more neutral. We are told that Tamna, aka the kingdom on Jeju island off the southern tip of the Korean peninsula, sent Princes Kumaye, Tora, Uma, and others with tribute.

So now we are getting back into the diplomatic swing of things. There had been one previous embassy—that of Gim Apsil of Silla, who had arrived just towards the end of the Jinshin War, but they were merely entertained in Tsukushi and sent back, probably because Ohoama’s court were still cleaning house.

Tamna, Silla, and Goguryeo—usually accompanied by Silla escorts—would be the main visitors to Yamato for a time. At this point, Silla was busy trying to get the Tang forces to leave the peninsula. This was partly assisted by the various uprisings in the captured territories of Goguryeo and Baekje—primarily up in Goguryeo. There were various attempts to restore the kingdom. It isn’t clear, but I suspect that the Goguryeo envoys we do eventually see were operating largely as a vassal state under Silla.

Tamna, on the other hand, seems to have been outside of the conflict, from what we see in the records, and it likely was out of the way of the majority of any fighting. They also seem to have had a different relationship with Yamato, based on some of the interactions.

It is very curious to me that the names of the people from Tamna seem like they could come from Yamato. Perhaps that is related in some way to theories that Tamna was one of the last hold-outs of continental proto-Japonic language prior to the ancestor of modern Korean gaining ascendancy. Or it could just be an accident of how things got copied down in Sinitic characters and then translated back out.

The Tamna mission arrived on the 8th day of the 6th intercalary month of 673. A Silla embassy arrived 7 days later, but rather than tribute, their mission was twofold—two ambassadors to offer congratulations to Ohoama and two to offer condolences on the late sovereign—though whether that means Naka no Oe or Ohotomo is not exactly clear. All of these arrived and would have been hosted, initially, in Tsukushi, probably at modern Fukuoka. The Silla envoys were accompanied by Escorts, who were briefly entertained and offered presents by the Dazaifu, the Yamato government extension on Kyushu, and then sent home. From then on, the envoys would be at the mercy of Yamato and their ships.

About a month and a half later, on the 20th day of the 8th month, Goguryeo envoys also showed up with tribute, accompanied by Silla escorts. Five days later, word arrived back from the court in Asuka. The Silla envoys who had come to offer congratulations to the sovereign on his ascension were to be sent onwards. Those who had just come with tribute, however, could leave it with the viceroy in Tsukushi. They specifically made this point to the Tamna envoys, whom they then suggested should head back soon, as the weather was about to turn, and they wouldn’t want to be stuck there when the monsoon season came.

The Tamna cohort weren’t just kicked out, however. The court did grant them and their king cap-rank. The envoys were given Upper Dai-otsu, which Yamato equated to the rank of a minister in Tamna.

The Silla envoys—about 27 in total—made their way to Naniwa. It took them a month, and they arrived in Naniwa on the 28th day of the 9th month. Their arrival was met with entertainments—musical performances and presents that were given to the envoys. This was all part of the standard diplomatic song and dance—quite literally, in this case.

We aren’t given details on everything. Presumably the envoys offered their congratulations, which likely included some presents from Silla, as well as a congratulatory message. We aren’t given exact details, but a little more than a month later, on the first day of the 11th month, envoy Gim Seungwon took his leave.

Meanwhile, the Goguryeo envoys, who, like Tamna, had arrived merely with tribute, were still in Tsukushi. On the 21st day of the 11th month, just over two months after they arrived, we are told that they were entertained at the Ohogohori in Tsukushi and were given presents based on their rank. The Ohogohori, or “Big District”, appears to mirror a similar area in Naniwa that was likewise known for hosting diplomatic envoys.

With the diplomatic niceties over, there was one more thing to do in this first year of the new reign: the thanksgiving ritual always held at the beginning of a new reign, the Daijosai, or oho-namematsuri. This is a harvest ritual where the newly enthroned sovereign offers new rice to the kami and then eats some himself. At least in the modern version, he gives thanks and prays to Amaterasu Ohomikami, as well as to the amatsu-kami and kunitsu-kami, the kami of heaven and earth.

The Daijosai shares a lot in common with another important annual festival, the Niinamesai, or the Feast of First Fruits. This is the traditional harvest festival, usually held in November. The Daijosai follows much the same form as the Niinamesai, and as such, in years where there is a new sovereign, and thus the Daijosai is held, the Niinamesai is not, since it would be duplicative.

Many of the rituals of the Daijosai are private affairs and not open to the public. There are various theories about what happens, but only those who are part of the ritual know for sure, and they are sworn to secrecy.

The first instance of the Daijosai in the Chronicles is during the reign of Shiraga Takehiko Kunioshi Waka Yamato Neko, aka Seinei Tennou, in the 5th century, but we should take that with a huge grain of salt. Remember, one of the purposes behind the chronicles was to explain how everything came to be, and saying “we just made it up” wasn’t really going to fly.

I’ve seen some sources suggest that the Daijosai can be attributed to the first reign of Ohoama’s mother, Takara Hime, aka Kougyoku Tennou. The term used in her reign, though is Niiname, which seems to refer to the annual Niinamesai, though she is the first in the Chronicles that seems to celebrate it in the first year of her reign, sharing with the Crown Prince and Ministers.

It is likely that the ritual is much older in origin. After all, giving the first fruits of the harvest to the kami to thank them for their assistance seems like the core of harvest festivals around the world. We see it mentioned as the Niinamesai in much of the rest of the Nihon Shoki, even back to the Age of the Gods, when it played an important part in the stories of Amaterasu and Susanowo.

It is in Ohoama’s reign, though, that it seems to first take on its character as a true ritual of the state. We see that the Nakatomi and the Imbe were involved. Together these two families oversaw much of the court ritual having to do with kami worship. We also know that the officials of the Jingikan, the Ministry of Kami Affairs, were also present, as they were all given presents for attending on the sovereign during the festival. We also see that the district governors of Harima and Tamba, which were both in the area of modern Hyougo Prefecture, as well as various laborers under them, were all recognized with presents as well. We can assume that this was because they provided the rice and other offerings used in the festival. In addition to the presents they received, the two governors were each given an extra grade of cap-rank.

Another Daijosai would be carried out in the first year of Ohoama’s successor, and from there on it seems to have become one of if not the major festival of a reign. It marks, in many ways, the end of the first year of ceremonies for the first year of a reign. And even in other years, the Niinamesai is often one of the pre-eminent festivals.

The Daijosai may have been the climax of the year in many ways, but the year was not quite done yet. We have two more entries, and both are related to Buddhism. First, on the 17th day of the 12th month, just twelve days after the Daijosai, Prince Mino and Ki no Omi no Katamaro were appointed Commissioners for the erection of the Great Temple of Takechi—aka the Ohomiya no Ohodera, also known as the Daikandaiji.

The Daikandaiji was a massive temple complex. It is thought that it was originally a relocation of Kudara Ohodera, and we have remains at the foot of Kaguyama—Mt. Kagu, in the Asuka region of modern Kashihara city. Many of the ruins, however, seem to date to a slightly later period, suggesting that the main temple buildings were rebuilt after Ohoama’s reign. Still, it is quite likely that he had people start the initial work.

In setting up the temple, of course it needed a head priest. And so Ohoama called upon a priest named Fukurin and made him an offer he couldn’t refuse… literally. Fukurin tried to object to being posted as the head priest. He said that he was too old to be in charge of the temple. Ohoama wasn’t having any of it. He had made up his mind, and Fukurin was in no position to refuse him.

A quick note on the two commissioners here. First off, I would note that Prince Mino here isn’t mentioned as having Princely rank. Instead, he is mentioned with the ministerial rank of Shoushi. Ki no Katamaro, on the other hand, is Lower Shoukin, several grades below. Once again, a bit of confusion in the ranks, as it were.

The final entry for the year 673 occurred 10 days after the erection of the great temple, and it was a fairly straightforward entry: The Buddhist Priest, Gijou, was made Shou-soudzu, or Junior Soudzu. Junior Soudzu was one of the government appointed positions of priests charged with overseeing the activities of the priests and temples and holding them to account as necessary. Originally there was the Soujou and the Soudzu, but they were later broken up into several different positions, likely due to the proliferation of Buddhism throughout the archipelago.

There doesn’t seem to be much on Gijou before this point, but we know that he would go on to live a pretty full life, passing away over thirty years later, in 706 CE. He would outlive Ohoama and his successor.

And with that, we come to the end of the first year. I am not planning to go year by year through this entire reign—in fact, we have already touched on a lot of the various recurring entries. But I do think that it is worth it to see how the Chronicles treat this first year for a reign that would have been considered pretty momentous to the people of the time.

Next episode we’ll continue going through the reign of Ohoama, aka Temmu Tennou. There is a lot going on, which, as I’ve said, will influence the nation for centuries—even up until the modern day.

Until then, if you like what we are doing, please tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

Thank you, also, to Ellen for their work editing the podcast.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Ellwood, R. S. (1973). The Feast of Kingship: Accession Ceremonies in Ancient Japan. Japan: Sophia University.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4.