Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we look at some of the improving foreign relations.

Silla

Silla is the most prominent foreign entity in contact with the Yamato court at this time. Furthermore, under King Munmu the Great they are at a high point in their history. With the help of the Tang Empire they have defeated Baekje and Goguryeo. Then, after years of struggle, they would also push the Tang out of the peninsula, at least past the Taedong river, which runs through Pyongyang. From the Taedong south—or Southeast—was what we often refer to as Unified Silla. For the first time, the peninsula was under a single authority, and it would start to bring a unification of culture as well as politics. It seems that Silla was also interested in mending fences with Yamato. The two had long had an adversarial relationship, but it seems that was changing.

Goguryeo

For a kingdom that was destroyed, Goguryeo continued to have quite the presence in the Chronicles. While Baekje and Nimna had both largely been given up as lost, Goguryeo, despite its apparent non-existence, refused to give up the ghost, as it were. This appears to be in part due to local rebellions and restoration efforts, but also thanks to official sponsorship by Silla, who no doubt realized that Goguryeo’s restoration kept the Tang dynasty busy. And so we see Goguryeo envoys to the Yamato court, though each time accompanied by Silla escorts.

Tamna

Tamna is on the island of Jeju, in the ocean south of the Korean peninsula. Though archaeological evidence suggests that they have had close ties with Yayoi Japan and with Baekje, among others, from at least the 1st century, we don’t see them show up in the Chronicles until the 7th. This may be because they were dealing with groups other than Yamato. With the fall of Baekje, the appearance of Tamna at the Yamato court appears to have grown. This could be coincidence just having to do with timing, though it is interesting that Tamna appears to show a lot of linguistic similarities in terms of names with the people of the Japanese archipelago. Alexander Vovin suggested that they were one of the last hold-outs of a continental proto-Japonic speaking group. Their language and entire way of life would eventually come under the sway of the rest of the peninsula before they were able to record too much of their own history, and so mostly we know of them through the writings of others.

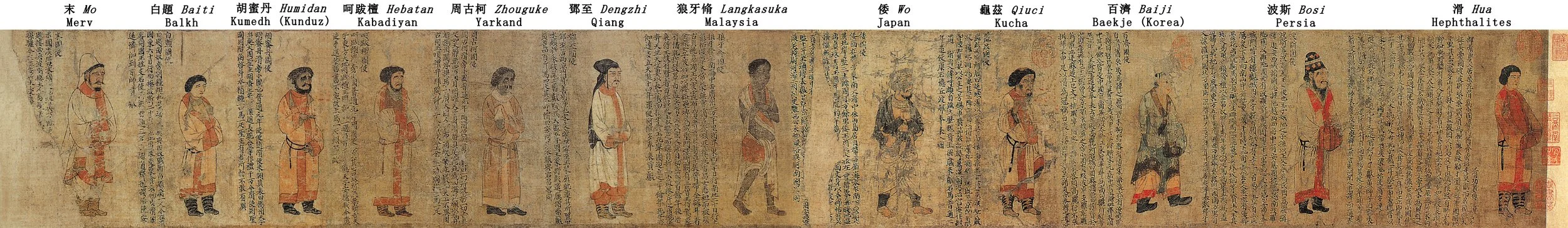

Tang Empire

The Tang Empire was expansive, dwarfing Yamato or Silla, but that expanse was also a problem. They had a massive border to defend, and they were regularly moving between fighting with Tibet and fighting on the Korean peninsula, which was no small feat. Eventually the peninsula would prove too much trouble, and they would relocate to Liaodong and focus on the former Goguryeo territory. The Tang court was also dealing with other issues. Tang Gaozong was the nominal ruler, but his wife, the Empress Wu Zetian, had been given unprecedented power, so that often it was her edicts that were actually being followed. For all of its power and might, we don’t see any more Tang envoys during this reign.

Mishihase

The Mishihase, or Sushen, are most likely the people also known as the Ohkotsk Sea Culture. We don’t have any of their own writings, and the term the Chronicles use for them appears to be appropriated from mainland references to another people altogether. But based on their activities and timeframe, the Ohkotsk Sea Culture is likely the group we can best identify them as. The Ohkotsk Sea Culture, itself, is a name for the culture that produced a variety of material goods found in archaeological excavations around the Ohkotsk Sea dated to around this time. The Ohokotsk Sea Culture appears to have had influence from or on the people we know today as the Nivkh and the Ainu—modern indigenous groups in Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the area near the mouth of the Amur River.

Non-Yamato Cultures on the Archipelago

We don’t hear much about the Emishi at this point in time, but there are plenty of other people who are outside of the Yamato political sphere, and who are often represented as culturally unique or distinct.

Hayato

The Hayato are perhaps the most famous group of the ones mentioned. They are from Southern Kyushu—the regions of Ata and Osumi. Ata is thought to be the area of Satsuma, and Osumi refers to the Osumi peninsula. We do see some differences in the material culture of these areas, but also plenty of similarities, suggesting that they may not be entirely distinct, just outside of Yamato’s formal political reach.

Tanegashima and Yakushima

These are two islands south of Kyushu, at the head of the chain of islands made from the volcanic sea ridge that travels from the archipelago all the way to the island of Taiwan, many of the islands of which make up the Ryukyuan, or Okinawan, island chain. Tanegashima is known to us, today, because it was one of the first places that Europeans landed and became an early hub of firearms production—but that was still centuries off. Yakushima is known today as a UNESCO world heritage site for its pristine forests. It has long been inhabited, but never tremendously so.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is episode 140: Improving Diplomatic Ties

Garyang Jyeongsan and Gim Hongsye looked out from the deck of their ship, tossing and turning in the sea. The waves were high, and the winds lashed at the ship, which rocked uncomfortably beneath their feet. Ocean spray struck them from below while rain pelted from above.

Through the torrential and unstable conditions, they looked out for their sister ship. It was their job to escort them, but in these rough seas, bobbing up and down, they were at the mercy of the elements. One minute they could see them, and then next it was nothing but a wall of water. Each time they caught a glimpse the other ship seemed further and further away. They tried calling out, but it was no use—even if they could normally have raised them, the fierce winds simply carried their voices out into the watery void. Eventually, they lost sight of them altogether.

When the winds died down and the seas settled, they looked for their companions, but they saw nothing, not even hints of wreckage on the ocean. They could only hope that their fellow pilots knew where they were going. As long as they could still sail, they should be able to make it to land—either to the islands to which they were headed, or back to the safety of the peninsula.

And so the escort ship continued on, even without a formal envoy to escort. They would hope for the best, or else they would explain what would happen, and hope that the Yamato court would understand.

The seas were anything but predictable, and diplomacy was certainly not for the faint of heart.

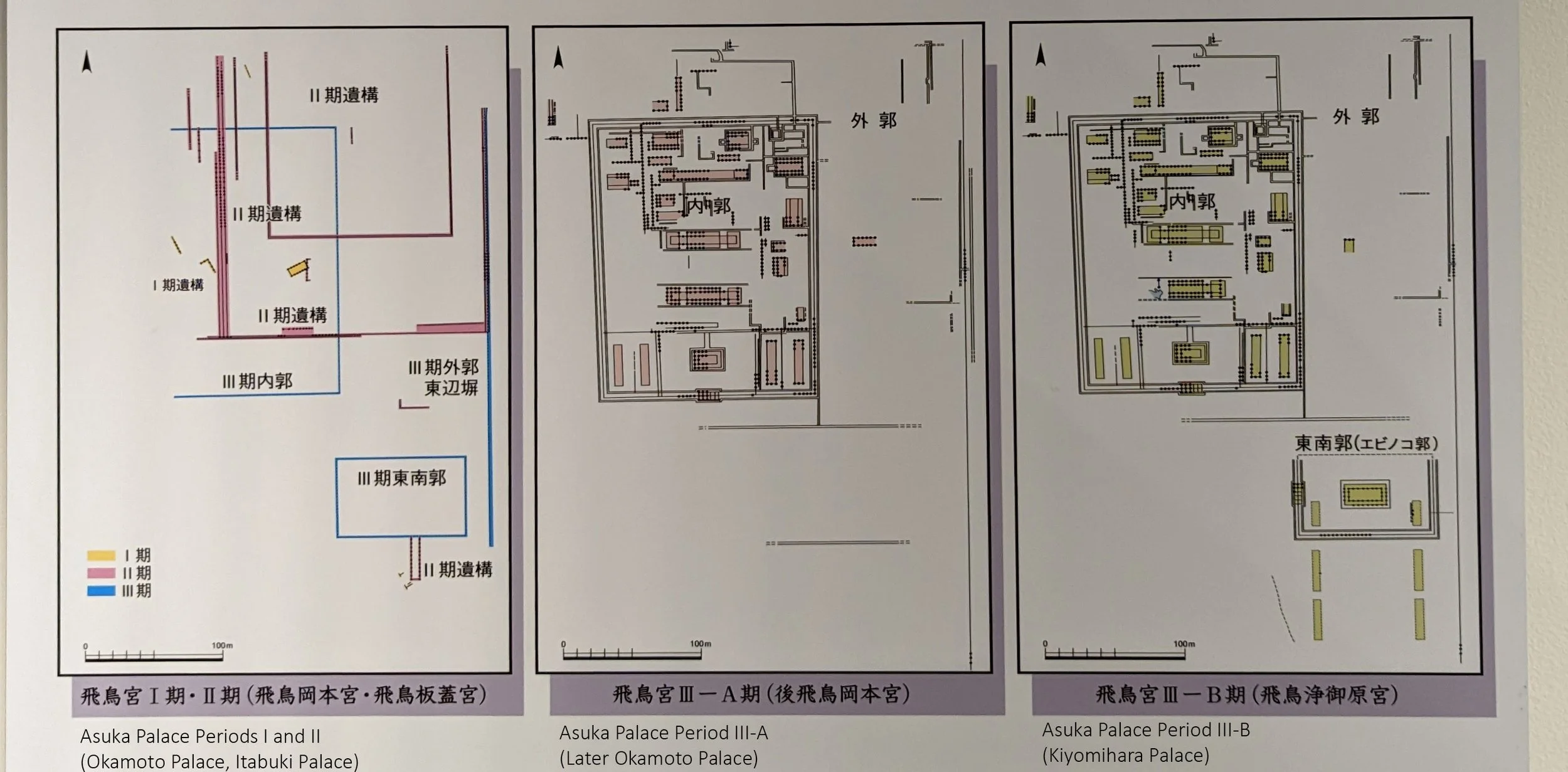

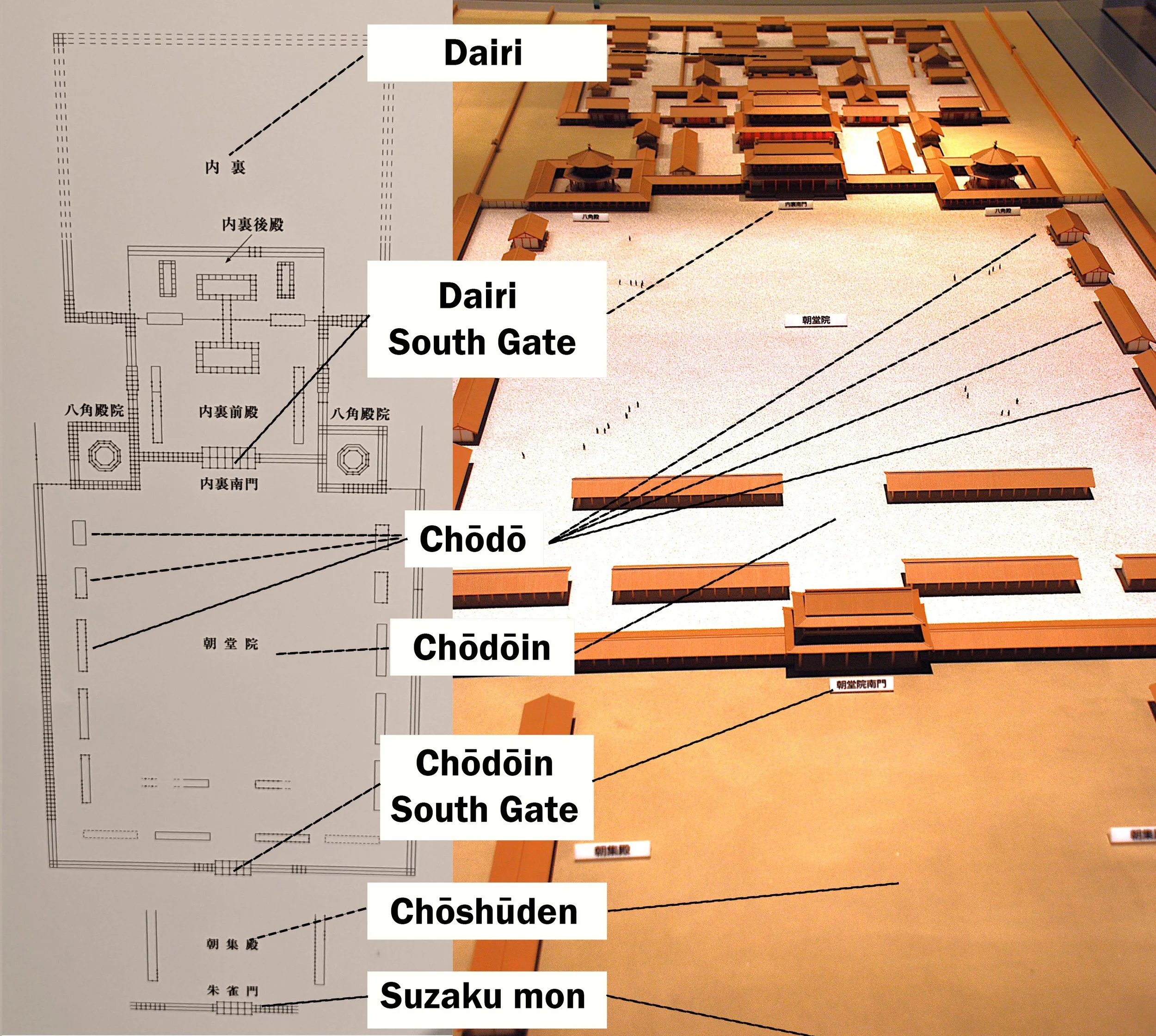

We are going through the period of the reign of Ohoama, aka Temmu Tennou. It started in 672, with the death of his brother, Naka no Oe, remembered as the sovereign Tenji Tenno, when Temmu took the throne from his nephew, Ohotomo, aka Kobun Tenno, in what would become known as the Jinshin no Ran. From that point, Ohoama continued the work of his brother in creating a government based on a continental model of laws and punishments—the Ritsuryo system. He accomplished this with assistance from his wife, Uno, and other members of the royal family—his own sons, but also nephews and other princes of the time. And so far most of our focus has been on the local goings on within the archipelago.

However, there was still plenty going on in the rest of the world, and though Yamato’s focus may have been on more local affairs, it was still engaged with the rest of the world—or at least with the polities of the Korean Peninsula and the Tang Dynasty. This episode we are going to look at Yamato’s foreign relations, and how they were changing, especially as things changed on the continent.

Up to this point, much of what had been happening in Yamato had been heavily influenced by the mainland in one way or another. And to begin our discussion, we really should backtrack a bit—all the way to the Battle of Baekgang in 663, which we discussed in Episode 124. That defeat would lead to the fall of Baekje, at the hands of the Silla-Tang alliance. The loss of their ally on the peninsula sent Yamato into a flurry of defensive activity. They erected fortresses on Tsushima, Kyushu, and along the Seto Inland Sea. They also moved the capital up to Ohotsu, a more easily defended point on the shores of Lake Biwa, and likewise reinforced various strategic points in the Home Provinces as well. These fortresses were built in the style and under the direction of many of the Baekje refugees now resettled in Yamato.

For years, the archipelago braced for an invasion by the Silla-Tang alliance. After all, with all that Yamato had done to support Baekje, it only made sense, from their perspective, for Silla and Tang to next come after them. Sure, there was still Goguryeo, but with the death of Yeon Gaesomun, Goguryeo would not last that long. With a unified peninsula, then why wouldn’t they next look to the archipelago?

And yet, the attack never came. While Yamato was building up its defenses, it seems that the alliance between Silla and Tang was not quite as strong as their victories on the battlefield may have made it seem. This is hardly surprising—the Tang and Silla were hardly operating on the same scale. That said, the Tang’s immense size, while bringing it great resources, also meant that it had an extremely large border to defend. They often utilized alliances with other states to achieve their ends. In fact, it seems fairly common for the Tang to seek alliances with states just beyond their borders against those states that were directly on their borders. In other words, they would effectively create a pincer maneuver by befriending the enemy of their enemy. Of course. Once they had defeated said enemy well, wouldn’t you know it, their former ally was now their newest bordering state.

In the case of the Silla-Tang alliance, it appears that at the start of the alliance, back in the days of Tang Taizong, the agreement, at least from Silla’s perspective, was that they would help each other against Goguryeo and Baekje, and then the Tang dynasty would leave the Korean peninsula to Silla. However, things didn’t go quite that smoothly. The fighting against Goguryeo and Baekje can be traced back to the 640s, but Tang Taizong passed away in 649, leaving the throne to his heir, Tang Gaozong. The Tang forces eventually helped Silla to take Baekje after the battle of Baekgang River in 663, and then Goguryeo fell in 668, but the Tang forces didn’t leave the peninsula. They remained in the former territories of Baekje and in Goguryeo, despite any former agreements. Ostensibly they were no doubt pointing to the continuing revolts and rebellions in both regions. While neither kingdom would fully reassert itself, it didn’t mean that there weren’t those who were trying. In fact, the first revolt in Goguryeo was in 669. There was also a revolt each year until 673. The last one had some staying power, as the Goguryeo rebels continued to hold out for about four years.

It is probably worth reminding ourselves that the Tang dynasty, during this time, had reached out on several occasions to Yamato, sending diplomatic missions, as had Silla. While the Yamato court may have been preparing for a Tang invasion, the Tang perspective seems different. They were preoccupied with the various revolts going on, and they had other problems. On their western border, they were having to contend with the kingdom of Tibet, for example. The Tibetan kingdom had a powerful influence on the southern route around the Taklamakan desert, which abuts the Tibetan plateau. The Tang court would have had to divert resources to defend their holdings in the western regions, and it is unlikely that they had any immediate designs on the archipelago, which I suspect was considered something of a backwater to them, at the time. In fact, Yamato would have been much more useful to the Tang as an ally to help maintain some pressure against Silla, with whom their relationship, no longer directed at a common enemy, was becoming somewhat tense.

In fact, just before Ohoama came to the throne, several events had occurred that would affect the Silla-Tang alliance.

The first event is more indirect—in 670, the Tibetan kingdom attacked the Tang empire. The fighting was intense, and required serious resources from both sides. Eventually the Tibetan forces were victorious, but not without a heavy toll on the Tibetan kingdom, which some attribute to the latter’s eventual demise. Their pyrrhic victory, however, was a defeat for the Tang, who also lost troops and resources in the fighting. Then, in 671, the Tang empire would suffer another loss as Silla would drive the Tang forces out of the territory of the former kingdom of Baekje.

With the Baekje territory under their control, it appears that Silla was also working to encourage some of rebellions in Goguryeo. This more than irked the Tang court, currently under the formal control of Tang Gaozong and the informal—but quite considerable—control of his wife, Wu Zetian, who some claim was the one actually calling most of the shots in the court at this point in time. Silla encouragement of restoration efforts in Goguryeo reached the Tang court in 674, in and in 675 we see that the Tang forces were sent to take back their foothold in the former Baekje territory. Tang defeated Silla at Gyeonggi, and Silla’s king, Munmu, sent a tribute mission to the Tang court, apologizing for their past behavior.

However, the Tang control could not be maintained, as they had to once again withdraw most of their troops from the peninsula to send them against the Tibetan kingdom once more. As soon as they did so, Silla once again renewed their attacks on Tang forces on the peninsula. And so, a year later, in 676, the Tang forces were back. They crossed the Yellow Sea to try and take back the Tang territories on the lower peninsula, but they were unsuccessful. Tang forces were defeated by Silla at Maeso Fortress in modern day Yeoncheon. After a bit more fighting, Silla ended up in control of all territory south of the Taedong River, which runs through Pyongyang, one of the ancient capitals of Goguryeo and the capital of modern North Korea. This meant that the Tang dynasty still held much of the territory of Goguryeo under their control.

With everything that was going on, perhaps that explains some of the apparently defensive measures that Yamato continued to take. For example, the second lunar month of 675, we know that Ohoama proceeded to Takayasu castle, likely as a kind of formal inspection. Then, in the 10th lunar month of 675 Ohoama commanded that everyone from the Princes down to the lowest rank were to provide the government with weapons. A year later, in the 9th month of 676, the Princes and Ministers sent agents to the capital and the Home Provinces and gave out weapons to each man. Similar edicts would be issued throughout the reign. So in 679 the court announced that in two years time, which is to say the year 681, there would be a review of the weapons and horses belonging to the Princes of the Blood, Ministers, and any public functionaries. And in that same year, barrier were erected for the first time on Mt. Tatsta and Mt. Afusaka, along with an outer line of fortifications at Naniwa.

While some of that no doubt also helped to control internal movements, it also would have been useful to prepare for the possibility of future invasions. And the work continued. In 683 we see a royal command to all of the various provinces to engage in military training. And in 684 it was decreed at that there would be an inspection in the 9th month of the following year—685—and they laid out the ceremonial rules, such as who would stand where, what the official clothing was to look like, etc.

Furthermore, there was also an edict that all civil and military officials should practice the use of arms and riding horses. They were expected to supply their own horses, weapons, and anything they would wear into battle. If they owned horses, they would be considered cavalry soldiers, while those who did not have their own horse would be trained as infantry. Either way, they would each receive training, and the court was determined to remove any obstacles and excuses that might arise. Anyone who didn’t comply would be punished. Non compliance could mean refusing to train, but it could also just mean that they did not provide the proper horses or equipment, or they let their equipment fall into a state of disrepair. Punishments could range from fines to outright flogging, should they be found guilty. On the other hand, those who practiced well would have any punishments against them for other crimes reduced by two degrees, even if it was for a capital crime. This only applied to previous crimes, however—if it seemed like you were trying to take advantage of this as a loophole to be able to get away with doing your own thing than the pardon itself would be considered null and void.

A year later, the aforementioned inspection was carried out by Princes Miyatokoro, Hirose, Naniwa, Takeda, and Mino. Two months later, the court issued another edict demanding that military equipment—specifically objects such as large or small horns, drums, flutes, flags, large bows, or catapults—should be stored at the government district house and not kept in private arsenals. The “large bow” in this case may be something like a ballista, though Aston translates it to crossbow—unfortunately, it isn’t exactly clear, and we don’t necessarily have a plethora of extant examples to point to regarding what they meant. Still, these seem to be focused on things that would be used by armies—especially the banners, large bows, and catapults. The musical instruments may seem odd, though music was often an important part of Tang dynasty military maneuvers. It was used to coordinate troops, raise morale, provide a marching rhythm, and more. Granted, much of this feels like something more continental, and it is unclear if music was regularly used in the archipelago. This could be more of Yamato trying to emulate the Tang dynasty rather than something that was commonplace on the archipelago. That might also explain the reference to the Ohoyumi and the catapults, or rock throwers.

All of this language having to do with military preparations could just be more of the same as far as the Sinicization of the Yamato government is concerned; attempts to further emulate what they understood of the civilized governments on the mainland—or at least their conception of those governments based on the various written works that they had imported. Still, I think it is relevant that there was a lot of uncertainty regarding the position of various polities and the potential for conflict. Each year could bring new changes to the political dynamic that could see military intervention make its way across the straits. And of course, there was always the possibility that Yamato itself might decide to raise a force of its own.

Throughout all of this, there was continued contact with the peninsula and other lands. Of course, Silla and Goguryeo were both represented when Ohoama came to the throne—though only the Silla ambassador made it to the ceremony, apparently. In the 7th lunar month of 675, Ohotomo no Muraji no Kunimaro was sent to Silla as the Chief envoy, along with Miyake no Kishi no Irishi. They likely got a chance to witness first-hand the tensions between Silla and the Tang court. The mission would return in the second lunar month of the following year, 676. Eight months later, Mononobe no Muarji no Maro and Yamashiro no Atahe no Momotari were both sent. That embassy also returned in the 2nd lunar month of the following year.

Meanwhile, it wasn’t just Yamato traveling to Silla—there were also envoys coming the other way. For example, in the 2nd lunar month of 675 we are told that Silla sent Prince Chyungweon as an ambassador. His retinue was apparently detained on Tsukushi while the actual envoy team went on to the Yamato capital. It took them about two months to get there, and then they stayed until the 8th lunar month, so about four months in total.

At the same time, in the third month, Goguryeo and Silla both sent “tribute” to Yamato. And in the 8th month, Prince Kumaki, from Tamna, arrived at Tsukushi as well. Tamna, as you may recall, refers to nation on the island known today as Jeju. The late Alexander Vovin suggested that the name originated from a proto-Japonic cognate with “Tanimura”, and many of the names seem to also bear out a possible Japonic influence on the island nation. Although they only somewhat recently show up in the Chronicles from our perspective, archaeological evidence suggests that they had trade with Yayoi Japan and Baekje since at least the first century. With the fall of Baekje, and the expansion of Yamato authority to more of the archipelago, we’ve seen a notable uptick in the communication between Tamna and Yamato noted in the record. A month after the arrival of Prince Kumaki in Tsukushi, aka Kyushu, it is noted that a Prince Koyo of Tamna arrived at Naniwa. The Tamna guests would stick around for almost a year, during which time they were presented with a ship and eventually returned in the 7th lunar month of the following year, 676. Tamna envoys, who had also shown up in 673, continued to be an annual presence at the Yamato court through the year 679, after which there is an apparent break in contact, picking back up in 684 and 685.

676 also saw a continuation of Silla representatives coming to the Yamato court, arriving in the 11th lunar month. That means they probably passed by the Yamato envoys heading the other way. Silla, under King Mumnu, now had complete control of the Korean peninsula south of the Taedong river. In the same month we also see another mission from Goguryeo, but the Chronicle also points out that the Goguryeo envoys had a Silla escort, indicating the alliance between Silla and those attempting to restore Goguryeo—or at least the area of Goguryeo under Tang control. The Tang, for their part, had pulled back their commandary to Liaodong, just west of the modern border between China and North Korea, today. Goguryeo would not go quietly, and the people of that ancient kingdom—one of the oldest on the peninsula—would continue to rise up and assert their independence for years to come.

The chronicles also record envoys from the somewhat mysterious northern Mishihase, or Sushen, thought to be people of the Okhotsk Sea culture from the Sakhalin islands. There were 11 of them, and they came with the Silla envoys, possibly indicating their influence on the continent and through the Amur river region. Previously, most of the contact had been through the regions of Koshi and the Emishi in modern Tohoku and Hokkaido. This seems to be their only major envoy to the Yamato court recorded in this reign.

Speaking of outside groups, in the 2nd lunar month of 677 we are told that there was an entertainment given to men of Tanegashima under the famous Tsuki tree west of Asukadera. Many people may know Tanegashima from the role it played in the Sengoku Period, when Europeans made contact and Tanegashima became a major hub of Sengoku era firearm manufacturing. At this point, however, it seems that it was still a largely independent island in the archipelago off the southern coast of Kyushu. Even southern Kyushu appears to have retained some significant cultural differences at this time, with the “Hayato” people being referenced in regards to southern Kyushu—we’ll talk about them in a bit as they showed up at the capital in 682.

Tanegashima is actually closer to Yakushima, another island considered to be separate, culturally, from Yamato, and could be considered the start of the chain of islands leading south to Amami Ohoshima and the other Ryukyuan islands. That said, Tanegashima and Yakushima are much closer to the main islands of the archipelago and show considerable influence, including Yayoi and Kofun cultural artifacts, connecting them more closely to those cultures, even if Yamato initially saw them as distinct in some way.

A formal Yamato envoy would head down to Tanegashima two years later, in the 11th lunar month of 679. It was headed up by Yamato no Umakahibe no Miyatsuko no Tsura and Kami no Sukuri no Koukan. The next reference to the mission comes in 681, when the envoys returned and presented a map of the island. They claimed that it was in the middle of the ocean, and that rice was always abundant. With a single sowing of rice it was said that they could get two harvests. Other products specifically mentioned were cape jasmine and bulrushes, though they then note that there were also many other products that they didn’t bother to list. This must have been considered quite the success, as the Yamato envoys were each awarded a grade of rank for their efforts. They also appear to have returned with some of the locals, as they were entertained again in Asuka—this time on the riverbank west of Asukadera, where various kinds of music were performed for them.

Tanegashima and Yakushima would be brought formally under Yamato hegemony in 702 with the creation of Tane province, but for now it was still considered separate. This was probably just the first part of the efforts to bring them into Yamato, proper.

Getting back to the Silla envoys who had arrived in 676, they appear to have remained for several months. In the third lunar month of 677 we are told that they, along with guests of lower rank—thirteen persons all told—were invited to the capital. Meanwhile, the escort envoys and others who had not been invited to the capital were entertained in Tsukushi and returned from there.

While this was going on, weather out in the straits drove a Silla boat to the island of Chikashima. Aboard was a Silla man accompanined by three attendants and three Buddhist priests. We aren’t told where they were going, but they were given shelter and when the Silla envoy, Kim Chyeonpyeong, returned home he left with those who had been driven ashore, as well.

The following year, 678, was not a great one for the Silla envoys. Garyang Jyeongsan and Gim Hongsye arrived at Tsukushi, but they were just the escorts. The actual envoys had been separated by a storm at sea and never arrived. In their place, the escort envoys were sent to the capital, probably to at least carry through with the rituals of diplomacy. This was in the first month of the following year, 679, and given when envoys had previously arrived, it suggests to me that they waited a few months, probably to see if the envoys’ ship eventually appeared and to give the court time to figure out what to do. A month later, the Goguryeo envoys arrived, still being accompanied by Silla escorts, also arrived.

Fortunately the Yamato envoys to Silla and elsewhere fared better. That year, 679, the envoys returned successfully from Silla, Goguryeo, and Tamna. Overall, though, I think it demonstrates that this wasn’t just a pleasure cruise. There was a very real possibility that one could get lost at sea. At the same time, one needed people of sufficient status to be able to carry diplomatic messages and appropriately represent the court in foreign lands. We often seen envoys later taking on greater positions of responsibility in the court, and so you didn’t have to go far to find those willing to take the risk for later rewards.

That same year, another tribute mission from Silla did manage to make the crossing successfully. And in this mission we are given more details, for they brought gold, silver, iron, sacrificial cauldrons with three feet, brocade, cloth, hides, horses, dogs, mules, and camels. And those were just the official gifts to the court. Silla also sent distinct presents for the sovereign, the queen, and the crown prince, namely gold, silver, swords, flags, and things of that nature.

This appears to demonstrate increasingly close ties between Silla and Yamato. All of that arrived in the 10th lunar month of 679, and they stayed through the 6th lunar month of 680—about 7 to 9 months all told, depending on if there were any intercalary months that year. In addition to entertaining the Silla envoys in Tsukushi—it is not mentioned if they made it to the capital—we are also told that in the 2nd lunar month, halfway through the envoys’ visit, eight labourers from Silla were sent back to their own country with gifts appropriate to their station.

Here I have to pause and wonder what exactly is meant by this. “Labourer” seems somewhat innocuous. I suspect that their presence in Yamato may have been less than voluntary, and I wonder if these were captured prisoners of war who could have been in Yamato now for over a decade. If so, this could have been a gesture indicating that the two sides were putting all of that nastiness with Baekje behind them, and Yamato was accepting Silla’s new role on the peninsula. Or maybe I’m reading too much into it, but it does seem to imply that Silla and Yamato were growing closer, something that Yamato would need if it wanted to have easy access, again, to the wider world.

Speaking of returning people, that seems to have been something of a common thread for this year, 680, as another mission from Goguryeo saw 19 Goguryeo men also returned to their country. These were condolence envoys who had come to mourn the death of Takara Hime—aka Saimei Tennou. They must have arrived in the midst of all that was happening peninsula, and as such they were detained. Their detention is somewhat interesting, when you think about it, since technically Baekje and Goguryeo—and thus Yamato—would have been on the same side against the Silla-Tang alliance. But perhaps it was just considered too dangerous to send them home, initially, and then the Tang had taken control of their home. It is unclear to me how much they were being held by Yamato and how much they were just men without a country for a time. This may reflect how things on the mainland were stabilizing again, at least from Yamato’s perspective. However, as we’ll discuss a bit later, it may have also been another attempt at restoring the Goguryeo kingdom by bringing back refugees, especially if they had connections with the old court. The Goguryeo envoys—both the recent mission and those who had been detained—would remain until the 5th lunar month of 681, when they finally took their leave. That year, there were numerous mission both from and to Silla and Goguryeo, and in the latter part of the year, Gim Chyungpyeong came once again, once more bearing gives of gold, silver, copper, iron, brocade, thin silk, deerskins, and fine cloth. They also brought gold, silver, flags of a rosy-colored brocade and skins for the sovereign, his queen, and the crown prince.

That said, the 681 envoys also brought grave news: King Munmu of Silla was dead. Munmu had reigned since 661, so he had overseen the conquest of Silla and Goguryeo. His regnal name in Japanese might be read as Monmu, or even “Bunbu”, referencing the blending of literary and cultural achievements seen as the pinnacle of noble attainment. He is known as Munmu the Great for unifying the peninsula under a single ruler—though much of the Goguryeo territory was still out of reach. Indeed he saw warfare and the betterment of his people, and it is no doubt significant that his death is recorded in the official records of the archipelago. He was succeeded by his son, who would reign as King Sinmun, though the succession wasn’t exactly smooth.

We are told that Munmu, knowing his time was short, requested that his son, the Crown Prince, be named king before they attended to Munmu’s own funerary arrangements, claiming that the throne should not sit vacant. This may have been prescient, as the same year Munmu died and Sinmun ascended to the throne there was a revolt, led by none other than Sinmun’s own father-in-law, Kim Heumdol. Heumdol may, himselve, have been more of a figurehead for other political factions in the court and military. Nonetheless, the attempted coup of 681 was quickly put down—the envoys in Yamato would likely only learn about everything after the dust had settled upon their return.

The following year, 682, we see another interesting note about kings, this time in regards to the Goguryeo envoys, whom we are told were sent by the King of Goguryeo. Ever since moving the commandery to Liaodong, the Tang empire had claimed dominion over the lands of Goguryeo north of the Taedong river. Originally they had administered it militarily, but in 677 they crowned a local, Bojang as the “King of Joseon”, using the old name for the region, and put him in charge of the Liaodong commandery. However, he was removed in 681, and sent into exile in Sichuan, because rather than suppressing revolt, he had actually encouraged restoration attempts, inviting back Goguryeo refugees, like those who had been detained in Yamato. Although Bojang himself was sent into exile, his descendants continued to claim sovereignty, so it may have been one of them that was making the claim to the “King of Goguryeo”, possibly with Silla’s blessing.

Later that year, 682, we see Hayato from Ohosumi and Ata—possibly meaning Satsuma—the southernmost point of Kyushu coming to the court in 682. They brought tribute and representatives of Ohosumi and Ata wrestled, with the Ohosumi wrestler emerging victorious. They were entertained west of Asukadera, and various kinds of music was performed and gifts were given. They were apparently quite the sight, as Buddhist priests and laiety all came out to watch.

Little is known for certain about the Hayato. We have shields that are attributed to them, but their association may have more to do with the fact that they were employed as ceremonial guards for a time at the palace. We do know that Southern Kyushu had various groups that were seen as culturally distinct from Yamato, although there is a lot of overlap in material culture. We also see early reports of the Kumaso, possibly two different groups, the Kuma and So, in earlier records, and the relationship between the Kumaso and the Hayato is not clearly defined.

What we do know is that southern Kyushu, for all that it shared with Yamato certain aspects of culture through the kofun period, for example, they also had their own traditions. For example, there is a particular burial tradition of underground kofun that is distinct to southern Kyushu. A great example of this can be found at the Saitobaru Kofun cluster in Miyazaki, which contains these unique southern Kyushu style burials along with more Yamato style keyhole shaped and circular type kofun. Miyazaki sits just north of the Ohosumi peninsula, in what was formerly the land of Hyuga, aka Himuka. This is also where a lot of the founding stories of the Heavenly grandchild were placed, and even today there is a shrine there to the Heavenly Rock Cave. In other words there are a lot of connections with Southern Kyushu, and given that the Chronicles were being written in the later 7th and early 8th centuries, it is an area of intense interest when trying to understand the origins of Yamato and Japanese history.

Unfortunately, nothing clearly tells us exactly how the Hayato were separate, but in the coming century they would both come under Yamato hegemony and rebel against it, time and again. This isn’t the first time they are mentioned, but it may be the first time that we see them as an actual people, in a factual entry as earlier references in the Chronicles are suspect.

Continuing on with our look at diplomacy during this period, the year 683 we see a continuation of the same patterns, with nothing too out of the ordinary. Same with most of 684 until the 12th lunar month. It is then that we see a Silla ship arrive with Hashi no Sukune no Wohi and Shirawi no Fubito no Hozen. They had both, previously been to the Tang empire to study, though we don’t have a record of them leaving for that or any other purpose. They are accompanied by Witsukahi no Muraji no Kobito and Tsukushi no Miyake no Muraji no Tokuko, both of whom had apparently been captured and taken by the Tang dynasty during the Baekje campaign. Apparently they had all traveled back from the Tang empire together to Silla, who then provided them passage to Yamato.

The timing of this suggests it may have had something to do with the changes going on in the Tang empire—changes that I desperately want to get into, but given that we are already a good ways into this current episode, I think I will leave it for later. But I will note this: Emperor Gaozong had passed away and his wife, Empress Wu Zetian, was now ruling as regent for her sons. Wu Zetian is probably the most famous empress in all of Chinese history, and while she held de facto power as a co-regent during her husband’s reign and as a regent during her sons’ reigns, she would actually ascend the throne herself in 690. Her reign as a woman during a time of heightened patriarchal tradition is particularly of note, and it leads us to wonder about the vilification that she received by the men who followed her rule. And I really want to get into all of that but, thematically, I think it better to wait. Those of you reading ahead in the syllabus—which is to say the Chronicles—probably know why. So let us just leave it there and say that the Tang was going through a few things, and that may explain why students were returning back in the company of former war captives.

A few months later, the Silla escort, Gim Mulyu, was sent home along with 7 people from Silla who had been washed ashore—presumably during a storm or other such event, again illustrating the dangers of taking to the ocean at this time. Perhaps related to that theme is the entry only a month later, which merely stated that Gim Jusan of Silla returned home. Gim Jusan was an envoy sent to Yamato in the 11th lunar month of 683. He was entertained in Tsukushi, and we are told that he returned to his own country on the 3rd month of 684. Now we are seeing an entry in the 4th month of 685 that this same person apparently returned home.

It is possible that something got mixed up, and that the Chroniclers were dealing with a typo in the records that made it seem like this took place a year later than it did. This was certainly an issue at this time, given all the math one had to do just to figure out what day it was. There is also the possibility that he returned on another embassy, but just wasn’t mentioned for some reason. The last possible explanation is that he somehow got lost and it took him a year to find his way back. Not entirely impossible back then, though I am a bit skeptical. Among other things, why would that note have found its way into the Chronicles in Yamato? While they were certainly using some continental sources, this seems like something they were talking about as far as him leaving the archipelago, rather than discussion of something happening elsewhere.

Speaking of happening elsewhere, I’m wondering about another event that happened around this time as well. In fact, it was while Gim Mulyu was still in the archipelago. For some reason the Yamato court granted rank to 147 individuals from Tang, Baekje, and Goguryeo. Interestingly, they don’t mention Silla. Furthermore, there is no real mention of any Tang envoys during this reign. In fact, there is hardly mention of the Tang dynasty at all. There is a mention of some 30 Tang men—captives, presumably—being sent to the Yamato court from Tsukushi. Those men were settled in Toutoumi, so there were men of Tang in the archipelago. But beyond that, there are only three other mentions of the Tang dynasty. One was when the students and war captives came back. Another was this note about giving rank to 147 individuals. Finally there is a similar record in 686, at the very end of the reign, where it is 34 persons who were given rank. This time it was to carpenters, diviners, physicians, students from Tang—possibly those who had just come back a year or so earlier.

So if there weren’t envoys from Tang, Goguryeo, and Baekje, who were these people and why were they being granted Yamato court rank? My assumption is that it was foreigners living in the archipelago, and being incorporated into the Yamato court system. Still, it is interesting that after the overtures by the Tang in the previous reign we have heard virtually nothing since then. Again, that is likely largely due to the conflicts between Tang and Silla, though now, things seem to be changing. The conflicts have settled down, and new rulers are in place, so we’ll see how things go.

Speaking of which, let’s finish up with the diplomatic exchanges in this reign. I’m only hitting some of the highlights here. First is the return from Silla, in the 5th month of 685, of Takamuku no Asomi no Maro and Tsuno no Asomi no Ushikahi. They had traveled to Silla in 684, and they did not come back emptyhanded. The new King of Silla presented them with gifts, including 2 horses, 3 dogs, 2 parrots, and 2 magpies. They also brought back the novice monks Kanjou and Ryoukan. Not bad, overall.

Then, 6 months later, another tribute mission came, but this one has an interesting—if somewhat questionable—note attached to it. It is said that the envoys Gim Jisyang and Gim Geonhun were sent to request “governance” and to bring tribute. This certainly go the court’s attention. They didn’t bring the envoys all the way to the capital, but they did send to them, in Tsukushi, Prince Kawachi, Ohotomo no Sukune no Yasumaro, Fujiwara no Asomi no Ohoshima, and Hodzumi no Asomi no Mushimaro. About three months later they send the musical performers from Kawaradera to provide entertainment during a banquet for the Silla envoy, and in payment some 5,000 bundles of rice rom the private lands attached to the queen’s palace were granted to the temple in gratitude.

The Silla tribute was then brought to the capital from Tsukushi. This time it was more than 100 items, including one fine horse, one mule, two dogs, a gold container inlaid with some kind of design, gold, silver, faint brocade, silk gauze, tiger and leopard skins, and a variety of medicines. In addition, as was now common, the envoys, Gim Jisyang and Gim Geonhun, apparently had personal gifts to give in the form of gold, silver, faint brocade, silk gauze, gold containers, screens, saddle hides, silk cloth, and more medicine. There were also gifts specifically for the sovereign, the queen, the Crown Prince, and for the various princes of the blood.

The court returned this favor with gifts to the envoys, presented at a banquet just for them, before sending them on their way.

A couple of notes. First off, it is interesting that they are entertained at Tsukushi rather than being invited to the capital, and I wonder if this was because the sovereign, Ohoama, wasn’t doing so well. This was all happening in 685 and 686, and the sovereign would pass away shortly afterwards. So it is possible that Ohoama just was not up to entertaining visitors at this time. Of course, the Chronicles often don’t tell us exactly why a given decision was made, only that it was. And sometimes not even that.

The other thing that seems curious is the mention of a request for governance. That almost sounds like Silla was asking to come under Yamato hegemony, which I seriously doubt. It may be that they were asking something along the lines of an alliance, but it is also possible that the scribes recording things for Yamato heard what they wanted to hear and so wrote it down in the light most favorable to Yamato laying claim to the peninsula.

Or perhaps I’m misunderstanding exactly what they were asking for. Maybe “governance” here means something else—perhaps just some kind of better relationship.

And with that, we’ll leave it for now. There is more developing in the next reign, but I think we want to wait until we get there. There are still a lot more things to cover in this reign before we move on—we haven’t even touched on the establishment of the new capital, on the various court events, not to mention some of the laws and punishments that this period is named for. And there is the minor issue of a rebellion. All of that will be dealt with. And then, after that, we get to the final reign of the Chronicles: the reign of Jitou Tennou. From there? Who knows.

It is the winter holiday season, so I hope everyone is enjoying themselves. Next episode will be the New Year’s recap, and then we should finish with this reign probably in January or early February.

Until then, if you like what we are doing, please tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

Thank you, also, to Ellen for their work editing the podcast.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Bentley, John R. (2025). Nihon Shoki: The Chronicles of Japan. ISBN 979-8-218634-67-4 pb

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4.