Previous Episodes

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode, we cover the rest of Mimaki Iribiko’s reign in the Chronicles and discuss a little more about what actual context may have looked like around that time—assuming his chronicle is talking about around the 3rd century, about the time of Queen Himiko.

To start with, let’s look at some of the connections I suggested with the Chronicles:

The Ministers of Yamato:

| Kanji | Tsunoda | Kidder | Soumare |

| 伊支馬 | Ikima | Ikima | Ikima |

| 彌馬升 | Mimasho | Mimato | Mimashi |

| 彌馬獲支 | Mimagushi | Mimawaki | Mimakaki |

| 奴佳鞮 | Nakato | Nakato | Nakatei |

Compare some of those with the sovereign, Mimaki Iribiko, and his son, Ikume Iribiko. Now, this isn’t evidence that any of this is remotely related, but we also know that there are differences just between the Chronicles themselves on the pronunciation of many of these individuals, so who knows just what the original pronunciation was?

Now when talking about all these places and what is going on, sometimes it just helps to have a map. One of the things we talk about in the episode is the extent to which the iron forging technology had extended across the archipelago. Note that these are forges, which can help shape iron, but they are not bloomeries, where they actually create the raw iron ingots from ore for smiths to then turn into useful items. The bloomeries appear to have operated as a monopoly on the mainland for some time, jealously guarding their secrets, and keeping the islands dependent on their trade.

Rough map, showing what may have been the extent of the early and later iron forging technologies. Based on geographic extent noted by Gina L. Barnes (Barnes, 2007) and a map by Ash_Crow, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

The early iron forging technology can be seen here as roughly described by Gina L. Barnes. I’ve used a map with the ancient provinces, though borders were not quite that specific in ancient days, and the coloring shows the rough extent—there may be other areas that just have not yet been discovered and some of the colored areas may have actually had no real access to the technology—in other words, this is for illustrative purposes, but I’d suggest checking some truly scholarly source for more rigorous data.

Now, the later technology relies on a tuyere, or tube, which allows air to be pushed into the forge, which in turn increases the combustion, increasing the heat that is produced. Higher temperatures allow for more efficient and different types of forging. I don’t want to get into the complexities of iron metallurgy right here, but basically iron’s properties can be controlled by a variety of mechanisms, including the temperature you heat it to, how fast or slow it cools down, physical work hardening (like when you bend a paper clip so many times and it gets a little harder just before it snaps), and then adulterating the iron with carbon or other elements. These can produce different shapes in the structure of the iron itself, which is why iron, cast iron, steel, etc. are all so different.

That said, would it have been enough of a leap to make these sites technologically superior? And was that enough? Or was it just that because these particular areas were connected, when they got the technology it spread in those areas where forging technology had not already been found? Why didn’t the previous areas adopt the new technology? Was it too much for them to change their established processes, while in areas where it had not been established it was easy to simply adopt the contemporary technology? I am not sure I could say.\

However, we can compare the extent of the iron working technology to the spread of the later keyhole tombs that showed up in the beginning of the kofun period. Only a few small examples appear before Hashihaka and the Makimuku cluster. Below maps show areas that archaeologically were fairly active—they appear to have chiefly or kingly activities—and then the regions where we find the actual kofun built.

Areas identified as having politically active areas in the late Yayoi to start of the Kofun period. Light areas identified by Sasaki (1995) and dark areas by Mizoguchi (2000), as noted in Barnes (2007). Original map by Ash_Crow, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Modified by author.

Areas with keyhole tombs identified by Mizoguchi (2009). Areas are not precise, and any polity may not have had actual control in all of the shaded regions. Dark areas had round keyhole tombs, while shaded areas had square or other keyhole tomb styles. Original map by Ash_Crow, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Modified by author.

The question in all this remains: Why is this spreading from Kinki—from the Makimuku area—outward and why not from Northern Kyushu? After all, Northern Kyushu is closer to the mainland and should have better trade linkages. It isn’t like the court at the base of Mt. Miwa could just fly past and on to the continent themselves.

In truth, we really don’t know, but there are several hypothesis. One is that the Nara Basin provided enough rice paddies for significant population growth and that their position between eastern and western Honshu made them a natural trading point. It still doesn’t quite explain why the round keyhole tombs proliferated quite as they did—was it submission, or competition, or something else? There doesn’t seem to be a single answer just yet, though historians and archaeologists continue provide their theories.

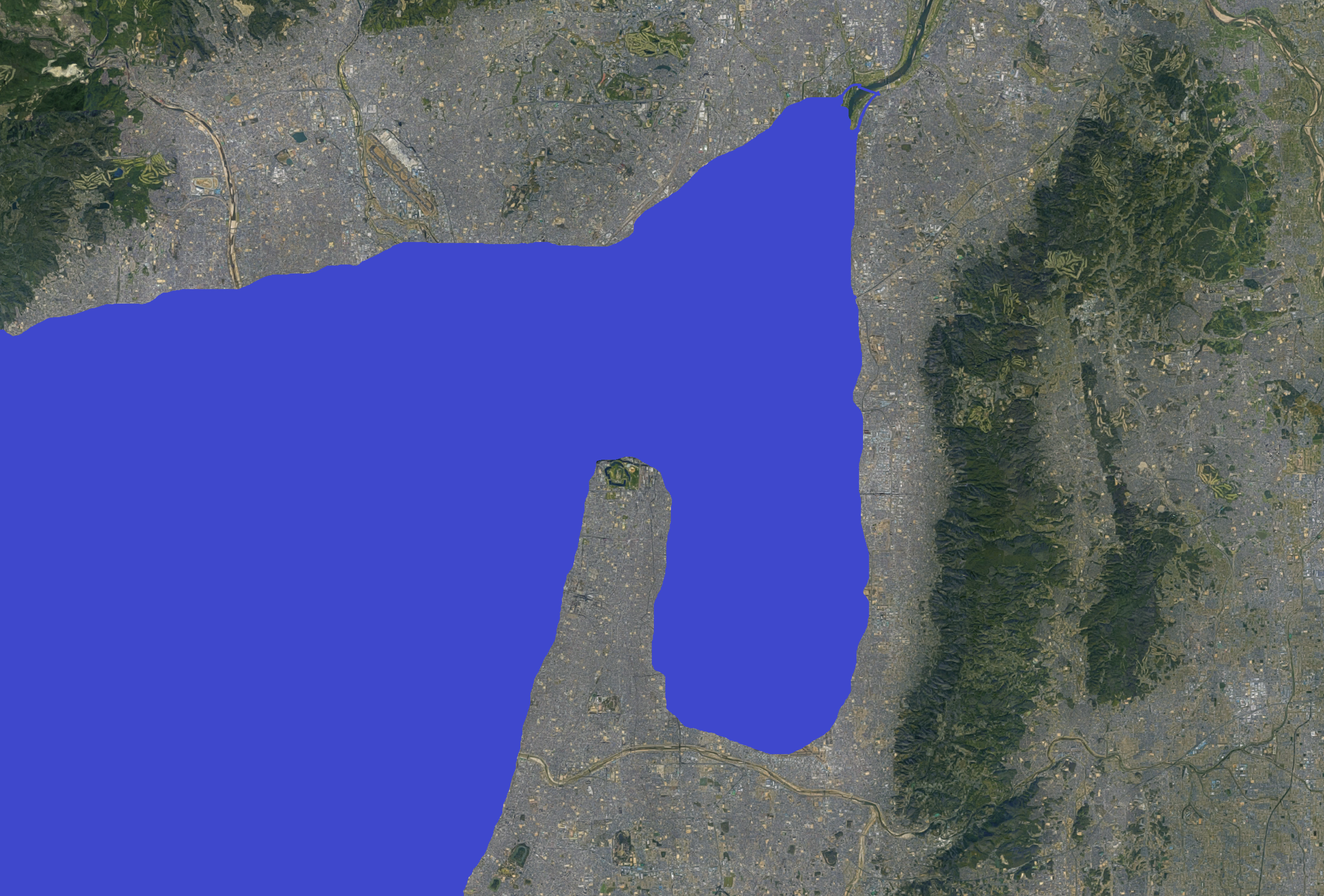

One more thing, while we are talking about territories and maps: let’s take a look at the areas that the Chronicles appear to cover.

Rough map of the areas that appear to be described in the Chronicles related to Mimaki Iribiko’s reign. Original map by Ash_Crow, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. Modified by author.

Now, this map is my own creation, as there is nothing so precise in the Chronicle, and even then, its claims seem far more grandiose than what is shown here, even. Yamato likely only directly controlled the area of the southeast Nara basin. How much direct control they had beyond that is unknown—they must have had some power, but there is no archaeological evidence suggesting a unified state as we would think of it with direct control to much extent until several centuries later. Still, the areas that are discussed do appear to be areas that can be correlated with both the non-local pottery found at Makimuku and with some of the other geographic signs seen in the earlier maps. Still, this is conjecture as the directions that the four generals took is unfortunately rather vague. For instance, was the Eastern Road just following the coast, and was there any movement in the central part of Eastern Honshu? This mountainous region may have taken time to bring into any particular state, as one imagines that the valleys could have had numerous settlements that had no particular affiliation outside their own local group.

On Kibi

So I hope there might be enough on Kibi to eventually pull together an episode just on this place—an apparent powerhouse during the early and Kofun periods, but perhaps not known so well as other areas of Japan. This is in part due to how it was carved up into various other provinces—something that was not uncommon. Koshi (越), meaning “to go beyond”, was broken into three provinces—Echizen (越前), Etchū (越中), and Echigo (越後)—using the other reading of the kanji for “Koshi”. A similar process happened with Kibi (吉備), but they simply used the final character, creating Bizen (備前), Bitchū (備中), and Bingo (備後). Later, they would break off another portion to be known as Mimasaka (美作).

Of course, for all of its size and apparent importance, we don’t hear quite as much about the gods of Kibi—not like those of Izumo—though there does seem to be some bleed-over across the mountains, which is not entirely surprising. While we may not know everything about Kibi’s greatness, its position in the Kofun period seems quite clear by the number of large kofun that still dot the landscape.

References

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Kishimoto, Naofumi (2013). Dual Kingship in the Kofun Period as Seen from the Keyhole Tombs. UrbanScope: e-Journal of the Urban-Culture Research Center, OCU. http://urbanscope.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/journal/pdf/vol004/01-kishimoto.pdf

Mizoguchi, Koji. (2009). Nodes and Edges: A Network Approach to Hierarchisation and State Formation in Japan. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology - J ANTHROPOL ARCHAEOL. 28. 14-26. 10.1016/j.jaa.2008.12.001.

Barnes, Gina L. (2007). State Formation in Japan: Emergence of a 4th-Century Ruling Elite. Routlede. ISBN 9780415596282

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Soumaré, Massimo (2007), Japan in Five Ancient Chinese Chronicles: Wo, the Land of Yamatai, and Queen Himiko. ISBN: 978-4-902075-22-9

Kidder, J. Edward (2007), Himiko and Japan's Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai: Archaeology, History, and Mythology. ISBN: 978-0824830359

Barnes, Gina L. (1988). Protohistoric Yamato: Archaeology of the First Japanese State. ISBN 0-915703-11-4

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Ledyard, G. (1975). Galloping along with the horseriders: looking for the founders of Japan. Journal of Japanese Studies. 1: 217-254

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1