Previous Episodes

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we are taking a bit of a tangent as we look into the record of men said to be from “Tukara”. By the way, in modern Japanese this is probably either Tsukara or Tokara. As we’ve mentioned in the past, pronunciations have shifted slightly over time.

There are three major theories that I’ve found for “Tukara”, though I wouldn’t be surprised to find more: Tukhara (aka Tokharistan), the Dvaravati Kingdom, or the Tokara islands of the Ryukyu island chain.

Tukhara and the Tokharoi

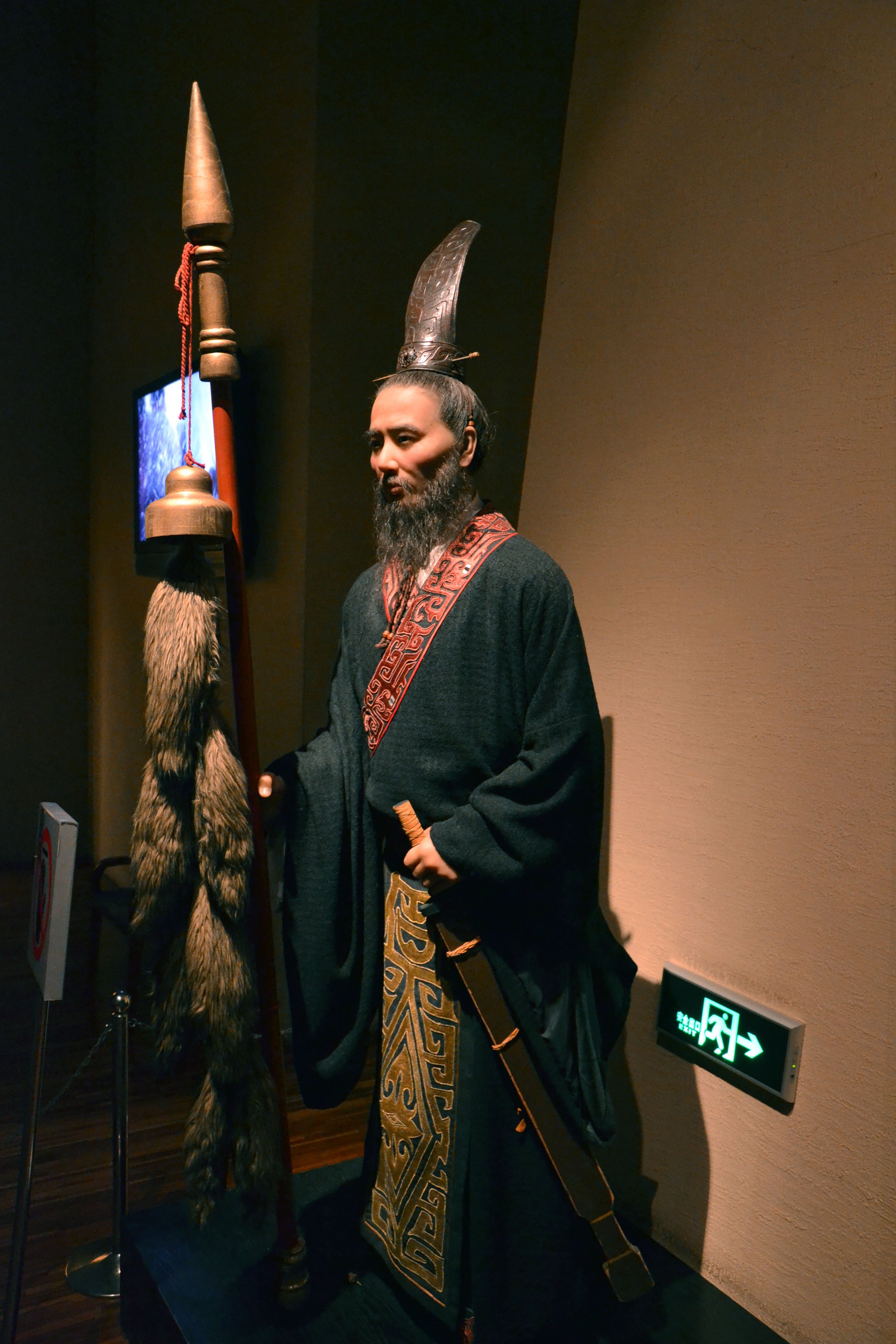

Representation of Zhang Qian and his yak-hair staff at the Shaanxi History Museum. Photo by author.

One location that is said to be “Tukara” is “Tukhara”, sometimes called Tokharistan, home of the “Tokharoi” according to Greek sources. This was at the far end of the Silk Road from the Japanese archipelago, in the area of modern Bactria. It is thought that they were the descendants of the Kushan Empire, themselves founded by members of “Kushana”, one of the polities that made up the confederacy known to the Han dynasty as the Yuezhi. After the Yuezhi were kicked out of the Tarim basin by the Xiongnu, the Han court attempted to send an ambassador, Zhang Qian, to negotiate with them to ally against their common enemy, but the Yuezhi politely refused the request.

Top of a stele in Xian erected during the Tang dynasty praising a new “Shining” religion, aka Christianity. Here you can see a cross etched into the top of the stele, which tells the history of the religion in the east, including mention of people from “Tukhara”. Photo by author.

There has been some speculation that the “Kushan” of the Kushan Empire might be a cognate with “Kucha”, an ancient city along the northern edge of the Tarim basin, in the territory thought to have belonged to the Yuezhi, before the Xiongnu pushed them out. Kucha, it turns out, is also the home of a language that is thought to have been called by in the old Turkic languages of the region, “twγry”, which was thought to be related to the “Tukhara” and the “Tokharoi”. Although that has largely been discredited, the Kuchean and Turfanian languages are still widely known as the “Tocharian” languages—often designated as Tocharian A and Tocharian B.

These languages, themselves, are a bit of a mystery as they are a “Centem” Indo-European language, thought to be similar to Celtic or Italic, while other Indo-European languages in the region—including the Indo-Iranian Bactrian language that was spoke in Tukhara— are “Satem” languages. “Centem” languages adopted the hard “c” or “k” sound for certain words in Proto-Indo-Eueropean, while “Satem” languages adopted the same sound to a sibilant “s” sound.

The possible connection between the “Tocharian” languages and Celtic and Italic further caught the attention of scholars who were also marveling at the well-preserved mummies of the region, some being three to four thousand years old and bearing features more associated with western Eurasia rather than the ethnic Han Chinese or the nomadic steppe people like the Xiongnu are believed to have been. These mummies even bore fabric in a form of plaid design that could have been at home in the ancient Hallstadt region of Central Europe. DNA evidence, however, suggests that they are, in fact, indigenous to the region, being part of an Ancient Northern Eurasian group of people. Truth is, we don’t know what languages they spoke, and many people passed through the Tarim basin over the years.

The Dvaravati Kingdom

This theory seems to hold a little less water than the others, but apparently the Sui and Tang new this as the “To-lo-po-ti” kingdom. The Dvaravati kingdom was a powerful ethnic Mon kingdom or confederation that arose in the modern region of Thailand, and it pre-dates the arrival of the Thai people. It lasted from about the 6th to the 12th century, and there is evidence that it traded not only with the Sui and Tang courts, but also with the middle east and even Rome.

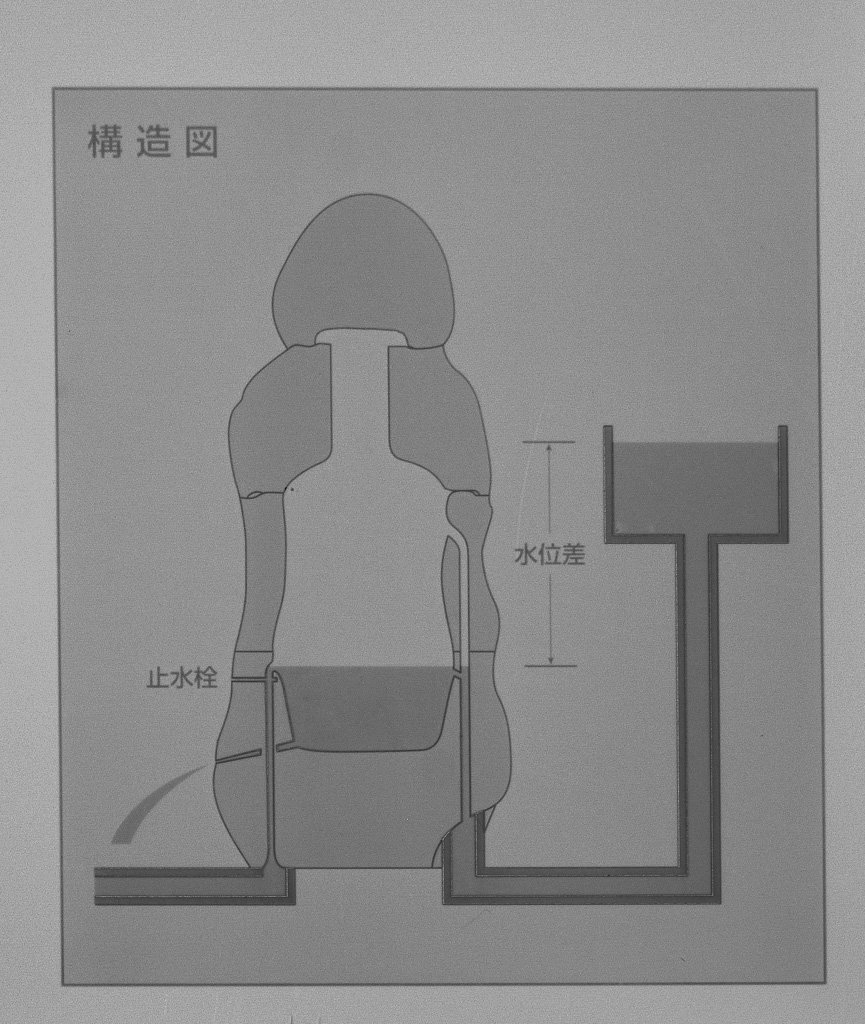

Base of an ancient temple or stupa at Pong Tuk, near the site where the Pong Tuk lamp was found. Photo by author.

Besides Arabic and Roman coins, one of the most spectacular finds is a 6th century Byzantine lamp in fields near modern Pong Tuk. This is also known to have been the site of an ancient Dvaravati settlement, with some ruins still visible, even today.

We don’t know precisely what happened to the Dvaravati Kingdom. It may have been a natural collapse over time. There is also some thought that the Gulf of Thailand may have once reached further inland, and as the Chaophraya river brought silt down from the north, this area filled in, and cities that were once on the coast found themselves miles upriver without the same access to ports for commerce and trade.

Tokara Islands

Perhaps the most logical conclusion, however, is that “Tukara” refers to the Tokara Islands. These are the islands between Amami Oshima and Tanegashima, immediately south of Kyushu. It is possible that the terms just used similar characters to phonetically spell out these different areas.

The Tokara islands are part of the larger Ryukyu archipelago, which extends all the way to Taiwan. We know that there has been contact with the Japanese archipelago since at least the Jomon era, but they didn’t follow into the Yayoi and Kofun periods quite as much. The islands closer to the Japanese archipelago saw greater and more immediate influence, but even they have retained a separate character. The islands were populated, at some point, by a Japonic speaking people, as the indigenous Ryukyuan language that evolved is one of the few members of the Japonic language family, including modern Japanese and possibly the language of Hachijo—another group of islands south of Tokyo.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. This is episode 119: The Question of “Tukara”

Traveling upon the ocean was never exactly safe. Squalls and storms could arise at any time, and there was always a chance that high winds and high waves could capsize a vessel. Most people who found themselves at the mercy of the ocean could do little but hold on and hope that they could ride out whatever adverse conditions they met with.

Many ships were lost without any explanation or understanding of what happened to them. They simply left the port and never came back home.

And so when the people saw the boat pulling up on the shores of Himuka, on the island of Tsukushi, they no doubt empathized with the voyagers’ plight. The crew looked bedraggled, and their clothing was unfamiliar. There were both men and women, and this didn’t look like your average fishing party. If anything was clear it was this: These folk weren’t from around here.

The locals brought out water and food. Meanwhile, runners were sent with a message: foreigners had arrived from a distant place. They then waited to see what the government was going to do.

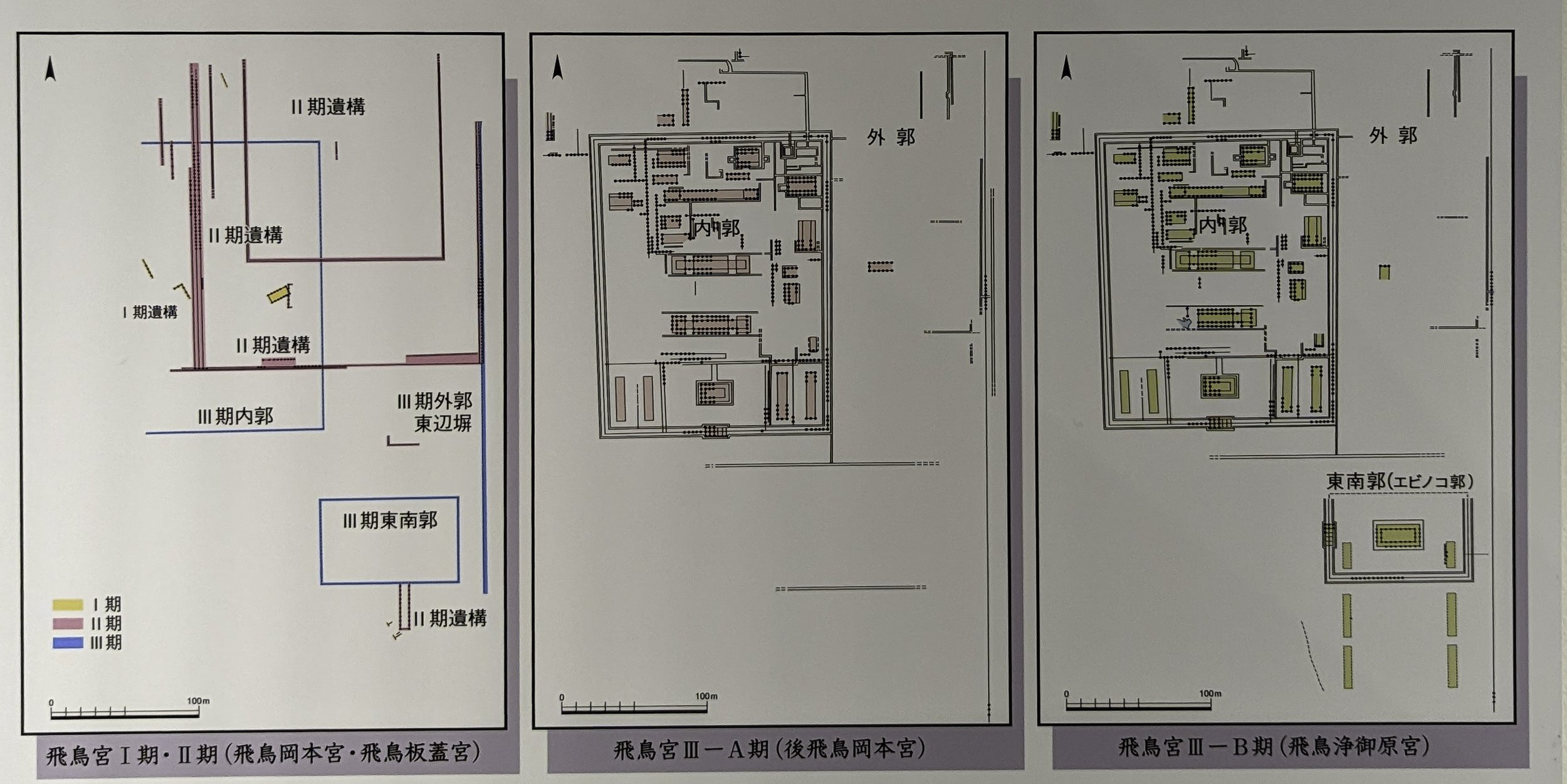

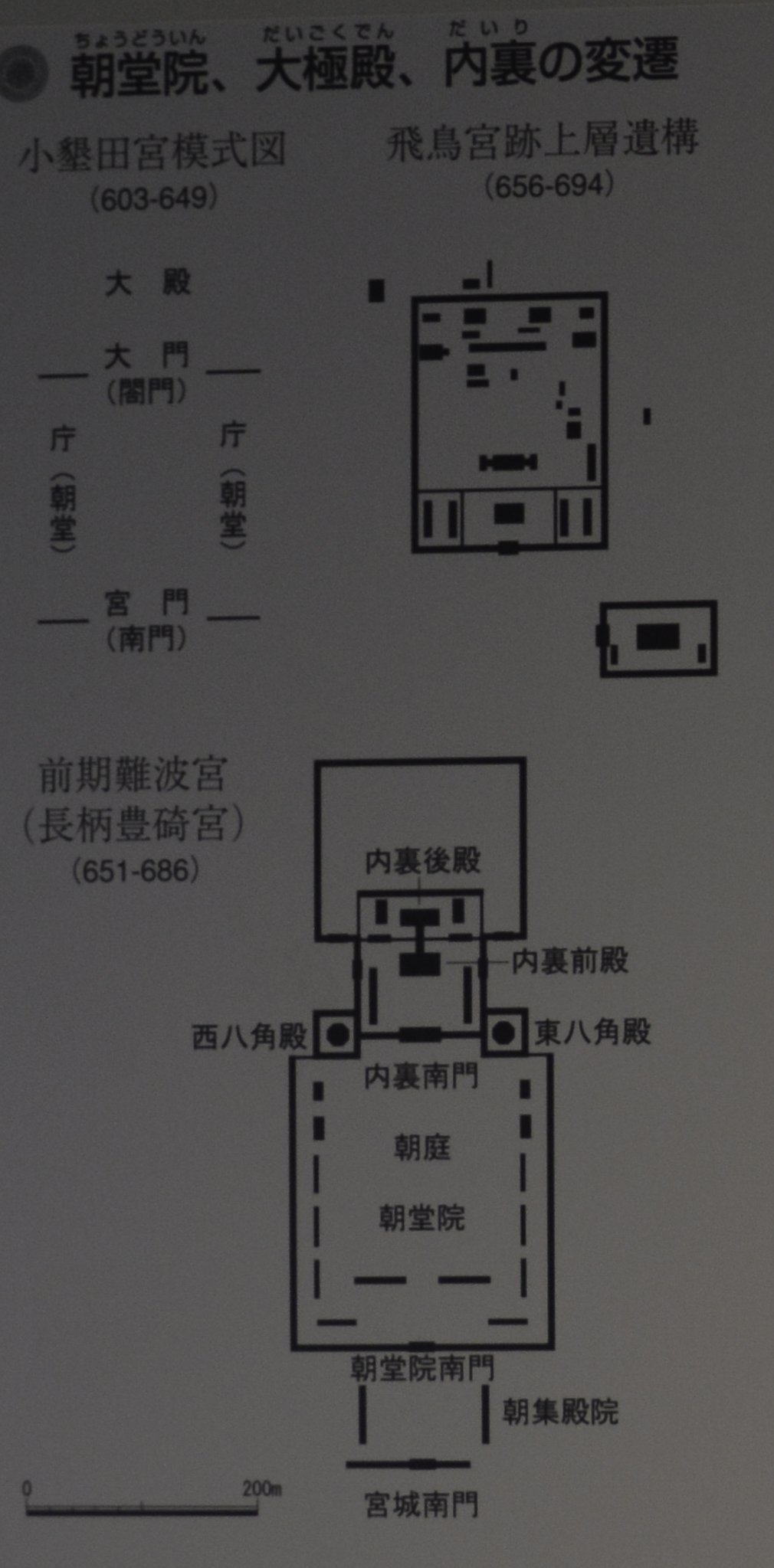

We are still in the second reign of Takara Hime, aka Saimei Tenno. Last episode we talked about the palaces constructed in Asuka, as well as some of the stone works that have been found from the period, and which appear to be referenced in the Nihon Shoki—at least tangentially. The episodes before that, we looked at the expeditions the court sent to the far north of Honshu and even past Honshu to Hokkaido.

This episode we’ll again be looking past the main islands of the archipelago to lands beyond. Specifically, we are going to focus on particularly intriguing references to people from a place called “Tukara”. We’ll talk about some of the ideas about where that might be, even if they’re a bit far-fetched. That’s because Tukara touches on the state of the larger world that Yamato was a part of, given its situation on the far eastern edge of what we know today as the Silk Road. And is this just an excuse for me to take a detour into some of the more interesting things going on outside the archipelago? No comment.

The first mention of a man from Tukara actually comes at the end of the reign of Karu, aka Koutoku Tennou. We are told that in the fourth month of 654 two men and two women of “Tukara” and one woman of “Sha’e” were driven by a storm to Hiuga.

Then, three years later, the story apparently picks up again, though possibly referring to a different group of people. On the 3rd day of the 7th month of 657, so during the second reign of Takara Hime, we now hear about two men and four women of the Land of Tukara—no mention of Sha’e—who drifted to Tsukushi, aka Kyushu. The Chronicles mention that these wayfarers first drifted to the island of Amami, and we’ll talk about that in a bit, but let’s get these puzzle pieces on the table, first. After those six people show up, the court sent for them by post-horse. They must have arrived by the 15th of that same month, because we are told that a model of Mt. Sumi was erected and they—the people from Tukara—were entertained, although there is another account that says they were from “Tora”.

The next mention is the 10th day of the 3rd month of 659, when a Man of Tukara and his wife, again woman of Sha’e, arrived. Then, on the 16th day of the 7th month of 660, we are told that the man of Tukara, Kenzuhashi Tatsuna, desired to return home and asked for an escort. He planned to pay his respects at the Great Country, i.e. the Tang court, and so he left his wife behind, taking tens of men with him.

All of these entries might refer to people regularly reaching Yamato from the south, from a place called “Tukara”. Alternately, this is a single event whose story has gotten distributed over several years, as we’ve seen happen before with the Chronicles. . One of the oddities of these entries is that the terms used are not consistent. “Tukara” is spelled at least two different ways, suggesting that it wasn’t a common placename like Silla or Baekje, or even the Mishihase. That does seem to suggest that the Chronicles were phonetically trying to find kanji, or the Sinitic characters, to match with the name they were hearing. I would also note that “Tukara” is given the status of a “kuni”—a land, country, or state—while “sha’e”, where some of the women are said to come from, is just that, “Sha’e”.

As for the name of at least one person from Tokara, Kenzuhashi Tatsuna, that certainly sounds like someone trying to fit a non-Japanese name into the orthography of the time. “Tatsuna” seems plausibly Japanese, but “Kenzuhashi” doesn’t fit quite as well into the naming structures we’ve seen to this point.

The location of “Tukara” and “Sha’e” are not clear in any way, and as such there has been a lot of speculation about them. While today there are placenames that fit those characters, whether or not these were the places being referenced at the time is hard to say.

I’ll actually start with “Sha’e”, which Aston translates as Shravasti, the capital of the ancient Indian kingdom of Kosala, in modern Uttar Pradesh. It is also where the Buddha, Siddartha Gautama, is said to have lived most of his life after his enlightenment. In Japanese this is “Sha’e-jou”, and like many Buddhist terms it likely comes through Sanskrit to Middle Chinese to Japanese. One—or possibly two—women from Shravasti making the journey to Yamato in the company of a man (or men) from Tukara seems quite the feat.

But then, where is “Tukara”? Well, we have at least three possible locations that I’ve seen bandied about. I’ll address them from the most distant to the closest option. These three options were Tokharistan, Dvaravati, and the Tokara islands.

We’ll start with Tokharistan on the far end of the Silk Road. And to start, let’s define what that “Silk Road” means. We’ve talked in past episodes about the “Western Regions”, past the Han-controlled territories of the Yellow River. The ancient Tang capital of Chang’an was built near to the home of the Qin dynasty, and even today you can go and see both the Tang tombs and the tomb of Qin Shihuangdi and his terracotta warriors, all within a short distance of Xi’an, the modern city built on the site of Chang’an. That city sits on a tributary of the Yellow River, but the main branch turns north around the border of modern Henan and the similarly sounding provinces of Shanxi and Shaanxi. Following it upstream, the river heads north into modern Mongolia, turns west, and then heads south again, creating what is known as the Ordos loop. Inside is the Ordos plateau, also known as the Ordos Basin. Continuing to follow the Yellow river south, on the western edge of the Ordos, you travel through Ningxia and Gansu—home of the Hexi, or Gansu, Corridor. That route eventually takes to Yumenguan, the Jade Gate, and Dunhuang. From there roads head north or south along the edge of the Taklamakan desert in the Tarim basin. The southern route travels along the edge of the Tibetan plateau, while the northern route traversed various oasis cities through Turpan, Kucha, to the city of Kashgar. Both routes made their way across the Pamirs and the Hindu Kush into South Asia.

We’ve brought up the Tarim Basin and the Silk Road a few times. This is the path that Buddhism appears to have taken to get to the Yellow River Basin and eventually to the Korean Peninsula and eastward to the Japanese archipelago. But I want to go a bit more into detail on things here, as there is an interesting side note about “Tukara” that I personally find rather fascinating, and thought this would be a fun time to share.

Back in Episode 79 we talked about how the Tarim basin used to be the home to a vast inland sea, which was fed by the meltwater from the Tianshan and Kunlun mountains. This sea eventually dwindled, though it was still large enough to be known to the Tang as the Puchang Sea. Today it has largely dried up, and it is mostly just the salt marshes of Lop Nur that remain. Evidence for this larger sea, however, can be observed in some of the burials found around the Tarim basin. These burials include the use of boat-shaped structures—a rather curious feature to be found out in the middle of the desert.

And it is the desert that was left behind as the waters receded that is key to much of what we know about life in the Tarim basin, as it has proven to be quite excellent at preserving organic material. This includes bodies, which dried out and naturally turned into mummies, including not only the wool clothing they were wearing, but also features such as hair and even decoration.

These “Tarim mummies”, as they have been collectively called, date from as early as 2100 BCE all the way up through the period of time we’re currently talking about, and have been found in several desert sites: Xiaohe, the earliest yet discovered; Loulan, near Lop Nur on the east of the Tarim Basin, dating from around 1800 BCE; Cherchen, on the southern edge of the Tarim Basin, dating from roughly 1000 BCE; and too many others to go into in huge detail. The intriguing thing about these burials is that many of them don’t have features typically associated with people of ethnic Han—which is to say traditional Chinese—ancestry, nor do they necessarily have the features associated with the Xiongnu and other steppe nomads. In addition they have colorful clothing made from wool and leather, with vivid designs. Some bodies near Hami, just east of the basin, were reported to have blonde to light brown hair, and their cloth showed radically different patterns from that found at Cherchen and Loulan, with patterns that could reasonably be compared with the plaids now common in places like Scotland and Ireland, and previously found in the Hallstadt salt mine in Central Europe from around 3500 BCE, from which it is thought the Celtic people may have originated.

At the same time that people—largely Westerners— were studying these mummies, another discovery in the Tarim basin was also making waves. This was the discovery of a brand new language. Actually, it was two languages—or possibly two dialects of a language—in many manuscripts, preserved in Kucha and Turpan. Once again, the dry desert conditions proved invaluable to maintain these manuscripts, which date from between the late 4th or early 5th century to the 8th century. They are written with a Brahmic script, similar to that used for Sanskrit, which appears in the Tarim Basin l by about the 2nd century, and we were able to translate them because many of the texts were copies of Buddhist scripture, which greatly helped scholars in deciphering the languages. These two languages were fascinating because they represented an as-yet undiscovered branch of the Indo-European language family. Furthermore, when compared to other Indo-European languages, they did not show nearly as much similarity with their neighbors as with languages on the far western end of the Indo-European language family. That is to say they were thought to be closer to Celtic and Italic languages than something like Indo-Iranian.

And now for a quick diversion within the diversion: “Centum” and “Satem” are general divisions of the Indo-European language families that was once thought to indicate a geographic divide in the languages. At its most basic, as Indo-European words changed over time, a labiovelar sound, something like “kw”, tended to evolve in one of two ways. In the Celtic and Italic languages, the “kw” went to a hard “k” sound, as represented in the classical pronunciation of the Latin word for 100: Centum. That same word, in the Avestan language—of the Indo-Iranian tree—is pronounced as “Satem”, with an “S” sound. So, you can look at Indo-European languages and divide them generally into “centum” languages, which preserve the hard “k”, or “Satem” languages that preserve the S. With me so far?

Getting back to these two newly-found languages in the Tarim Basin, the weird thing is that they were “Centum” languages. Most Centum languages are from pretty far away, though: they are generally found in western Europe or around the Mediterranean, as opposed to the Satem languages, such as Indo-Aryan, Iranian, Armernian, or even Baltic Slavic languages, which are much closer to the Tarim Basin.

So if the theory were true that the “Centum” family of Indo-European languages developed in the West and “Satem” languages developed in the East, then that would seem to indicate that a group of a “Centum” speaking people must have migrated eastward, through the various Satem speaking people, and settled in the Tarim Basin many thousands of years ago.

And what evidence do we have of people who look very different from the modern population, living in the Tarim Basin area long before, and wearing clothing similar to what we associated with the progenitors of the Celts?

For many, it seemed to be somewhat obvious, if still incredible, that the speakers of this language were likely the descendants of the mummies who, in the terminology of the time, had been identified as being of Caucasoid ancestry. A theory developed that these people were an offshoot of a group called the Yamnaya culture, which may have arisen around modern Ukraine as an admixture between the European Hunter Gatherers and the Caucasian Hunter Gatherers, around 3300-2600 BCE. This was challenged in 2021 when a genetic study was performed on some of the mummies in the Tarim basin, as well as several from the Dzungarian basin, to the northeast. That study suggested that the people of the Dzungarian basin had genetic ties to the people of the Afanasievo people, from Southern Siberia. The Afanasievo people are connected to the Yamnayan culture.

It should be noted that there has long been a fascination in Western anthropology and related sciences with racial identification—and often not in a healthy way. As you may recall, the Ainu were identified as “Caucasoid” by some people largely because of things like the men’s beards and lighter colored hair, which differ greatly from a large part of the Japanese population. However, that claim has been repeatedly refuted and debunked.

And similarly, the truth is, none of these Tarim mummy burials were in a period of written anything, so we can’t conclusively associated them with these fascinating Indo-European languages. There are thousands of years between the various burials and the manuscripts. These people left no notes stashed in pockets that give us their life story. And Language is not Genetics is not Culture. Any group may adopt a given language for a variety of reasons. . Still, given what we know, it is possible that the ancient people of the Tarim basin spoke some form of “Proto-Kuchean”, but it is just as likely that this language was brought in by people from Dzungaria at some point.

So why does all this matter to us? Well, remember how we were talking about someone from Tukara? The Kuchean language, at least, is referred to in an ancient Turkic source as belonging to “Twgry”, which led several scholars to draw a link between this and the kingdom and people called Tukara and the Tokharoi. This leads us on another bit of a chase through history.

Now if you recall, back in Episode 79, we talked about Zhang Qian. In 128 BCE, he attempted to cross the Silk Road through the territory of the Xiongnu on a mission for the Han court. Some fifty years earlier, the Xiongnu had defeated the Yuezhi. They held territory in the oasis towns along the north of the Taklamakan dessert, from about the Turpan basin west to the Pamirs. The Xiongnu were causing problems for the Han, who thought that if they could contact the remaining Yuezhi they could make common cause with them and harass the Xiongnu from both sides. Zhang Qian’s story is quite remarkable: he started out with an escort of some 99 men and a translator. Unfortunately, he was captured and enslaved by the Xiongnu during his journey, and he is even said to have had a wife and fathered a child. He remained a captive for thirteen years, but nonetheless, he was able to escape with his family and he made it to the Great Yuezhi on the far side of the Pamirs, but apparently the Yuezhi weren’t interested in a treaty against the Xiongnu. The Pamirs were apparently enough of a barrier and they were thriving in their new land. And so Zhang Qian crossed back again through Xiongnu territory, this time taking the southern route around the Tarim basin. He was still captured by the Xiongnu, who spared his life. He escaped, again, two years later, returning to the Han court. Of the original 100 explorers, only two returned: Zhang Qian and his translator. While he hadn’t obtained an alliance, he was able to detail the cultures of the area of the Yuezhi.

Many feel that the Kushan Empire, which is generally said to have existed from about 30 to 375 CE,was formed from the Kushana people who were part of the Yuezhi who fled the Xiongnu. In other words, they were originally from further north, around the Tarim Basin, and had been chased out and settled down in regions that included Bactria (as in the Bactrian camel). Zhang Qian describes reaching the Dayuan Kingdom in the Ferghana valley, then traveling south to an area that was the home of the Great Yuezhi or Da Yuezhi.

And after the Kushan empire fell, we know there was a state in the upper regions of the Oxus river, centered on the city of Balkh, in the former territory of the Kushan empire. known as “Tokara”. Geographically, this matches up how Zhang Qian described the home of the Da Yuezhi. Furthermore, some scholars reconstruct the reading of the Sinic characters used for “Yuezhi” as originally having an optional reading of something like “Togwar”, but that is certainly not the most common reconstructed reading of those characters. Greek sources describe this area as the home of the Tokharoi, or the Tokaran People. The term “Tukhara” is also found in Sanskrit, and this kingdom was also said to have sent ambassadors to the Southern Liang and Tang dynasties.

We aren’t exactly certain of where these Tokharan people came from, but as we’ve just described, there’s a prevailing theory that they were the remnants of the Yuezhi and Kushana people originally from the Tarim Basin. We know that in the 6th century they came under the rule of the Gokturk Khaganate, which once spanned from the Liao river basin to the Black Sea. In the 7th and 8th centuries they came under the rule of the Tang Empire, where they were known by very similar characters as those used to write “Tukara” in the Nihon Shoki. On top of this, we see Tokharans traveling the Silk Road, all the way to the Tang court. Furthermore, Tokharans that settled in Chang’an took the surname “Zhi” from the ethnonym “Yuezhi”, seemingly laying claim to and giving validation to the identity used back in the Han dynasty.

So, we have a Turkic record describing the Kuchean people (as in, from Kucha in the Tarim Basin) as “Twgry”, and we have a kingdom in Bactria called Tokara and populated (according to the Greeks) by people called Tokharoi. You can see how this one term has been a fascinating rabbit hole in the study of the Silk Roads and their history. And some scholars understandably suggested that perhaps the Indo-European languags found in Kucha and Turpan were actually related to this “Tokhara” – and therefore should be called “Tocharian”, specifically Tocharian A (Kuchean) or Tocharian B (Turfanian).

The problem is that if the Tokharans were speaking “Tocharian” then you wouldn’t expect to just see it at Kucha and Turpan, which are about the middle of the road between Tokhara and the Tang dynasty, and which had long been under Gokturk rule. You would also expect to see it in the areas of Bactria associated with Tokhara. However, that isn’t what we see. Instead, we see that Bactria was the home of local Bactrian language—an Eastern Iranian language, which, though it is part of the Indo European language family, it is not closely related to Tocharian as far as we can tell.

It is possible that the people of Kucha referred to themselves as something similar to “Twgry”, or “Tochari”, but we should also remember that comes from a Turkic source, and it could have been an exonym not related to what they called themselves. I should also note that language is not people. It is also possible that a particular ethnonym was maintained separately by two groups that may have been connected politically but which came to speak different languages for whatever reason. There could be a connection between the names, or it could even be that the same or similar exonym was used for different groups.

So, that was a lot and a bit of a ramble, but a lot of things that I find interesting—even if they aren’t as connected as they may appear. We have the Tarim mummies, which are, today, held at a museum in modern Urumqi. Whether they had any connection with Europe or not, they remain a fascinating study for the wealth of material items found in and around the Tarim basin and similar locations. And then there is the saga of the Tocharian languages—or perhaps more appropriately the Kuchean-Turfanian languages: Indo-European languages that seem to be well outside of where we would expect to find them.

Finally, just past the Pamirs, we get to the land of Tokhara or Tokharistan. Even without anything else, we know that they had contact with the court. Perhaps our castaways were from this land? The name is certainly similar to what we see in the Nihon Shoki, using some of the same characters.

All in all, art and other information suggest that the area of the Tarim basin and the Silk Road in general were quite cosmopolitan, with many different people from different regions of the world. Bactria retained Hellenic influences ever since the conquests of Alexander of Macedonia, aka Alexander the Great, and Sogdian and Persian traders regularly brought their caravans through the region to trade. And once the Tang dynasty controlled all of the routes, that just made travel that much easier, and many people traveled back and forth.

So from that perspective, it is possible that one or more people from Tukhara may have made the crossing from their home all the way to the Tang court, but if they did so, the question still remains: why would they be in a boat? Utilizing overland routes, they would have hit Chang’an or Louyang, the dual capitals of the Tang empire, well before they hit the ocean. However, the Nihon Shoki says that these voyagers first came ashore at Amami and then later says that they were trying to get to the Tang court.

Now there was another “Silk Road” that isn’t as often mentioned: the sea route, following the coast of south Asia, around through the Malacca strait and north along the Asian coast. This route is sometimes viewed more in terms of the “spice” road

If these voyagers set out to get to the Tang court by boat, they would have to have traveled south to the Indian Ocean—possibly traveling through Shravasti or Sha’e, depending on the route they chose to take—and then around the Malacca strait—unless they made it on foot all the way to Southeast Asia. And then they would have taken a boat up the coast.

Why do that instead of taking the overland route? They could likely have traveled directly to the Tang court over the overland silk road. Even the from Southeast Asia could have traveled up through Yunnan and made their way to the Tang court that way. In fact, Zhang Qian had wondered something similar when he made it to the site of the new home of the Yuezhi, in Bactria. Even then, in the 2nd century, he saw products in the marketplace that he identified as coming from around Szechuan. That would mean south of the Han dynasty, and he couldn’t figure out how those trade routes might exist and they weren’t already known to the court. Merchants would have had to traverse the dangerous mountains if they wanted to avoid being caught by the Xiongnu, who controlled the entire region.

After returning to the Han court, Zhang Qian actually went out on another expedition to the south, trying to find the southern trade routes, but apparently was not able to do so. That said, we do see, in later centuries, the trade routes open up between the area of the Sichuan basin and South Asia. We also see the migrations of people further south, and there may have even been some Roman merchants who traveled up this route to find their way to the Han court, though those accounts are not without their own controversy.

In either case, whether by land or sea, these trade routes were not always open. In some cases, seasonal weather, such as monsoons, might dictate movement back and forth, while political realities were also a factor. Still, it is worth remembering that even though most people were largely concerned with affairs in their own backyard, the world was still more connected than people give it credit for. Tang dynasty pottery made its way to the east coast of Africa, and ostriches were brought all the way to Chang’an.

As for the travelers from Tukhara and why they would take this long and very round-about method of travel, it is possible that they were just explorers, seeking new routes, or even on some kind of pilgrimage. Either way, they would have been way off course.

But if they did pass through Southeast Asia, that would match up with another theory about what “Tukara” meant: that it actually refers to the Dvaravati kingdom in what is now modern Thailand.

The Dvaravati Kingdom was a Mon political entity that rose up around the 6th century. It even sent embassies to the Sui and Tang courts. This is even before the temple complexes in Siem Reap, such as Preah Ko and the more famous Angkor Wat. And it was during this time that the ethnic Tai people are thought to have started migrating south from Yunnan, possibly due to pressures from the expanding Sui and Tang empires. Today, most of what remains of the Dvaravati kingdom are the ruins of ancient stone temples, showing a heavy Indic influence, and even early Buddhist practices as well.

“Dvaravati” may not actually be the name of the kingdom but it comes from an inscription on a coin found from about that time. The Chinese refer to it as “To-lo-po-ti” in contemporary records. It may not even have been a kingdom, but more of a confederation of city-states—it is hard to piece everything together. That it was well connected, though, is clear from the archaeological record. In Dvaravati sites, we see coins from as far as Rome, and we even have a lamp found in modern Pong Tuk that appears to match similar examples from the Byzantine Empire in the 6th century. Note that this doesn’t mean it arrived in the 6th century—similarly with the coins—but the Dvaravati state lasted until the 12th century. If that was the case, perhaps there were some women from a place called “Shravasti” or similar, especially given the Indic influence in the region.

Now, given the location of the Dvaravati, it wouldn’t be so farfetched to think that someone might sail up from the Gulf of Thailand and end up off-course, though it does mean sailing up the entire Ryukyuan chain or really running off course and finding yourself adrift on the East China sea. And if they were headed to the Tang court, perhaps they did have translators or knew Chinese, since Yamato was unlikely to know the Mon language of Dvaravati and people from Dvaravati probably wouldn’t know the Japonic language. Unless, perhaps, they were communicating through Buddhist priests via Sanskrit.

We’ve now heard two possibilities for Tukara, both pretty far afield: the region of Tokara in Bactria, and the Dvaravati kingdom in Southeast Asia. That said, the third and simplest explanation—and the one favored by Aston in his translation of the Nihon Shoki—is that Tukara is actually referring to a place in the Ryukyu island chain. Specifically, there is a “Tokara” archipelago, which spans between Yakushima and Amami-Oshima. This is part of the Nansei islands, and the closest part of the Ryukyuan island chain to the main Japanese archipelago. This is the most likely theory, and could account for the entry talking about Amami. It is easy to see how sailors could end up adrift, too far north, and come to shore in Hyuga, aka Himuka, on the east side of Kyushu.

It certainly would make more sense for them to be from this area of the Ryukyuan archipelago than from anywhere else. From Yakushima to Amami-Oshima is the closest part of the island chain to Kyushu, and as we see in the entry from the Shoku Nihongi, those three places seem to have been connected as being near to Japan. So what was going on down there, anyway?

Well, first off, let’s remember that the Ryukyuan archipelago is not just the island of Okinawa, but a series of islands that go from Kyushu all the way to the island of Taiwan. Geographically speaking, they are all part of the same volcanic ridge extending southward. The size of the islands and their distance from each other does vary, however, creating some natural barriers in the form of large stretches of open water, which have shaped how various groups developed on the islands.

Humans came to the islands around the same time they were reaching the Japanese mainland. In fact, some of our only early skeletal remains for early humans in Japan actually come from either the Ryukyuan peninsula in the south or around Hokkaido to the north, and that has to do with the acidity of the soil in much of mainland Japan.

Based on genetic studies, we know that at least two groups appear to have inhabited the islands from early times. One group appears to be related to the Jomon people of Japan, while the other appears to be more related to the indigenous people of Taiwan, who, themselves, appear to have been the ancestors of many Austronesian people. Just as some groups followed islands to the south of Taiwan, some appear to have headed north. However, they only made it so far. As far as I know there is no evidence they made it past Miyakoshima, the northernmost island in the Sakishima islands. Miyako island is separated from the next large island, Okinawa, by a large strait, known as the Miyako Strait, though sometimes called the Kerama gap in English. It is a 250km wide stretch of open ocean, which is quite the distance for anyone to travel, even for Austronesian people of Taiwan, who had likely not developed the extraordinary navigational technologies that the people who would become the Pacific Islanders would discover.

People on the Ryukyu island chain appear to have been in contact with the people of the Japanese archipelago since at least the Jomon period, and some of the material artifacts demonstrate a cultural connection. That was likely impacted by the Akahoya eruption, about 3500 years ago, and then re-established at a later date. We certainly see sea shells and corals trade to the people of the Japanese islands from fairly early on.

Unlike the people on the Japanese archipelago, the people of the Ryukyuan archipelago did not really adopt the Yayoi and later Kofun culture. They weren’t building large, mounded tombs, and they retained the character of a hunter-gatherer society, rather than transitioning to a largely agricultural way of life. The pottery does change in parts of Okinawa, which makes sense given the connections between the regions.

Unfortunately, there is a lot we don’t know about life in the islands around this time. We don’t exactly have written records, other than things like the entries in the Nihon Shoki, and those are hardly the most detailed of accounts. In the reign of Kashikiya Hime, aka Suiko Tennou, we see people from Yakushima, which is, along with Tanegashima, one of the largest islands at the northern end of the Ryukyu chain, just before you hit Kagoshima and the Osumi peninsula on the southern tip of Kyushu. The islands past that would be the Tokara islands, until you hit the large island of Amami.

So you can see how it would make sense that the people from “Tokara” would make sense to be from the area between Yakushima and Amami, and in many ways this explanation seems too good to be true. There are a only a few things that make this a bit peculiar. First, this doesn’t really explain the woman from “Sha’e” in any compelling way that I can see. Second, the name, Kenzuhashi Tatsuna doesn’t seem to fit with what we generally know about early Japonic names, and the modern Ryukyuan language certainly is a Japonic language, but there are still plenty of possible explanations. There is also the connection of Tokara with “Tokan”, which is mentioned in an entry in 699 in the Shoku Nihongi, the Chronicle that follows on, quite literally to the Nihon Shoki. Why would they call it “Tokan” instead of “Tokara” so soon after? Also, why would these voyagers go back to their country by way of the Tang court? Unless, of course, that is where they were headed in the first place. In which case, did the Man from Tukara intentionally leave his wife in Yamato, or was she something of a hostage while they continued on their mission?

And so those are the theories. The man from “Tukara” could be from Tokhara, or Tokharistan, at the far end of the Silk Road. Or it could have been referring to the Dvaravati Kingdom, in modern Thailand.

Still, in the end, Occam’s razor suggests that the simplest answer is that these were actually individuals from the Tokara islands in the Ryukyuan archipelago. It is possible that they were from Amami, not that they drifted there. More likely, a group from Amami drifted ashore in Kyushu as they were trying to find a route to the Tang court, as they claimed. Instead they found themselves taking a detour to the court of Yamato, instead.

And we could have stuck with that story, but I thought that maybe, just maybe, this would be a good time to reflect once again on how connected everything was. Because even if they weren’t from Dvaravati, that Kingdom was still trading with Rome and with the Tang. And the Tang controlled the majority of the overland silk road through the Tarim basin. We even know that someone from Tukhara made it to Chang’an, because they were mentioned on a stele that talked about an Asian sect of Christianity, the “Shining Religion”, that was praised and allowed to set up shop in the Tang capital, along with Persian Manicheans and Zoroastrians. Regardless of where these specific people may have been from, the world was clearly growing only more connected, and prospering, as well.

Next episode we’ll continue to look at how things were faring between the archipelago and the continent.

Until then thank you for listening and for all of your support.

If you like what we are doing, please tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

Thank you, also, to Ellen for their work editing the podcast.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Zhang, F., Ning, C., Scott, A. et al. The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies. Nature 599, 256–261 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04052-7

Hansen, V. (2012). The Silk Road: a new history. Oxford ; New York, Oxford University Press.

Beckwith, C.I. (2009) Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press, Princeton/Oxford. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

Boulnois, Luce (2005). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants. Hong Kong: Odyssey Books & Guides. pp. 311–335. ISBN 962-217-721-2.

Mallory, J. P., & Mair, V. H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. London: Thames & Hudson

Barber, E. J. W. (1999). The mummies of Urumchi. New York, W.W. Norton & Company.

Frye, R. N. 1. (1996). The heritage of Central Asia from antiquity to the Turkish expansion. Princeton, Markus Wiener Publishers.

Brown, Rober L.; MacDonnell, Anna M. (1989), "The Pong Tuk Lamp: A Reconsideration". The Journal of the Siam Society, vol. 77, pt. 2, 1989. pp. 9-20.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4