Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

Happy New Year!

Welcome to our 2026 recap. This episode we look back on the past year, but also try to make sure that we prepare for the next year. We’ll cover the big events and then go into some of the major themes that we’ve seen over the year. For that, we’ll also cover some of the previous history that has led up to the start of things this year.

This year we’ve covered the end of the reign of Takara Hime (Saimei Tennō), through the reigns of Naka no Ōe (Tenji Tennō) and into the reign of Ōama (Temmu Tennō)—not to mention the possible (if short) reign of Ōtomo (Kōbun Tennō). We saw an expanded contact with the continent—and an expanded international world, in general. We saw students from the archipelago studying with the famous monk Xuanzang, who traveled all the way to India.

But then war came. Iki no Hakatoko and others in the same embassy were held under house arrest in the Tang court while they attacked Yamato’s ally, Baekje. They deposed king Wicha of Baekje, and Yamato was drawn into the conflict. At the Battle of Baekgang river, Yamato forces suffered a tremendous defeat. Yamato and those Baekje allies that could join them fled to the archipelago, where the government built fortresses and set up a defensive posture should the Tang and Silla attack them next.

But the attack never came. The capital was moved to Afumi, but that was anything but a popular move. After the Jinshin War, which put Ōama on the throne, they moved back to Asuka. There, Ōama had been continuing the work of his brother, shaping the Ritsuryō state.

In the coming year we’ll see through the end of Ōama’s reign as we continue to march towards the end of the Nihon Shoki. After that, we’ll have to see, but I expect we’ll want to talk about the Nihon Shoki some and then look at the Shoku Nihongi—the continuing court chronicles.

-

Shinnen Akemashite! Happy New Year and Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is the New Year’s Recap episode for 2026!

Here’s hoping that everyone has had a great new year. I’m not sure about everyone else, but this past year seemed particularly long, and yet what we have covered on this podcast is only a relatively small part of the history of Yamato, so let’s get into it.

And in case anyone is wondering, this is covering episodes 118 to episode 140, though we will likely dip a little bit into the past as well, just to ensure we have context, where needed.

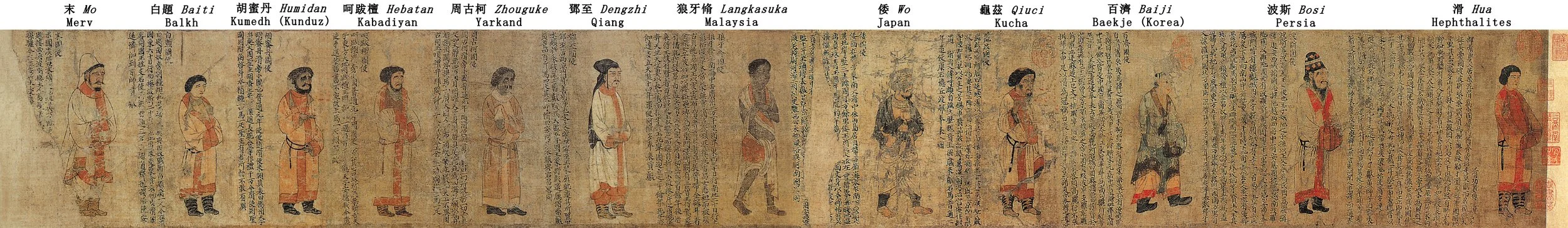

We started last year in the 650’s, in the second reign of Takara Hime, where we know her as Saimei Tennou. We discussed Yamato’s place in the larger world, especially in connection with the Silk Road. In fact, we spent several episodes focused on the wider world, which Yamato was learning about through students, ambassadors, and visitors from far off lands. Of course, that all came to a head at the Battle of Baekgang, when Yamato and their ally, Baekje, were defeated by a coalition of Tang and Silla forces, putting an end to the Kingdom of Baekje and driving Yamato to fall back and reinforce the archipelago.

This was also the start of the formal reign of Naka no Oe, who would go on to be known as Tenji Tennou. Naka no Oe would be a major proponent of substantial reforms to the Yamato government, as well as moving the capital to a new, more defensible location called Ohotsu, on the shores of Lake Biwa, in the land of Afumi. He also introduced new concepts of time through water clocks both in Asuka and in the Afumi capital.

Upon Naka no Oe’s death, almost immediately, violence broke out between the Yamato court’s ruling council led by Naka no Oe’s son, Prince Ohotomo, and Naka no Oe’s brother, Prince Ohoama. Ohoama would emerge victorious and ascend the throne, being known as Temmu Tennou. During his reign he took his brother’s government and placed upon it his own stamp. He reinvigorated Shinto rites while also patronizing Buddhism. Meanwhile, relations with the continent appear to be improving.

So that is the summary, let’s take a look at what we discussed in more detail.

First off, back to the reign of Takara Hime, aka Saimei Tennou—as opposed to her first reign, where she is known as Kougyoku Tennou. Takara Hime came back to the throne in 654 after a nine-year hiatus, having abdicated in 645 when her son, Prince Naka no Oe, had killed Soga no Iruka in front of her at court, violently assassinating one of the most powerful men in Yamato. Naka no Oe had then gone on to take out Soga no Iruka’s father, Soga no Emishi, a few days later. Upon abdicating, Taka Hime’s brother, Prince Karu, aka Koutoku Tennou, took the throne, but there are many that suggest that the real power in court was Naka no Oe and his allies—men such as the famous Nakatomi no Kamatari. When Karu passed away, Naka no Oe still did not take the throne, officially, and instead it reverted back to his mother.

Takara Hime is interesting in that she is officially recognized as a sovereign and yet she came to the throne when her husband, known as Jomei Tenno, passed away, even though neither of her parents were sovereigns themselves. This may have something to do with the fact that much of the actual power at the time was being executed by individuals other than the reigning sovereign. First it was the Soga family—Soga no Emishi and Soga no Iruka—but then it was Naka no Oe and his gaggle of officials. This makes it hard to gauge Takara Hime’s own agency versus that of her son’s.

Still, the archipelago flourished during her reign. This was due, in no small part, to the growing connectivity between the Japanese archipelago and the continent—and from there to the rest of the world. And that world was expanding.

We see mention of the men from “Tukara” and a woman—or women—from Shravastri. Of course it is possible, even likely, that these were a misunderstanding—it is most likely that these were individuals from the Ryukyuan archipelago and that the Chroniclers bungled the transcription, using known toponyms from the Sinitic lexicon rather than creating new ones for these places. However, it speaks to the fact that there were toponyms to pull from because the court had at least the idea of these other places. And remember, we had Wa students studying with the famous monk Xuanzang, who, himself, had traveled the silk road all the way out to Gandhara and around to India, the birthplace of Buddhism. The accounts and stories of other lands and peoples were available—at least to those with access to the continent. This helped firm up the Japanese archipelago’s location at the end of a vast trading network, which we know as the Silk Road. Indeed, we find various material goods showing up in the islands, as well as the artisans that were imported to help build Buddhist temples.

And just as all of this is happening, we hit a rough patch in relations between Yamato and the Tang dynasty. In fact, in one of our most detailed accounts of an embassy to date, thanks to the writings of one Iki no Hakatoko. Because the fateful embassy of 659 saw the Tang take the odd step of refusing to let the embassy return to Yamato.

It turns out that the Tang, who had, for some time now, been in contact with Silla, had entered into an alliance and were about to invade Baekje. It was presumed that if the Yamato embassy left the Tang court they might alert Baekje, their ally, that something was up. And so it was safer to place them under house arrest until the invasion popped off.

Sure enough, the invasion was launched and in less than a year King Wicha of Baekje and much of the Baekje court had been captured. With the initial invasion successful, the Yamato embassy was released, but that is hardly the end of the story. Baekje had sent a request to Yamato for support, but it came too late for Yamato to muster the forces necessary. That said, some factions of the Baekje court remained, and one of their Princes was still in Yamato. And so, as they had done in the past, Yamato sailed across the strait with the goal of restoring a royal heir to the throne.

Unfortunately, this was not quite as simple as it had been, previously. For one thing, the Tang forces were still in Baekje, and the fight became long and drawn out. Things finally came to a head in the early months of 663, at the mouth of the Baekgang river—known in Japanese as Hakusuki-no-e. This was a naval battle, and Yamato had more ships and was also likely more skilled on the water. After all, much of the Tang fighting was on land or rivers, while the Wa, an island nation, had been crossing the straits and raiding the peninsula for centuries. Even with all of the resources of the Tang empire, there was still every reason to think that the forces from the archipelago could pull off a victory. However, it was not to be. The Tang forces stayed near the head of the river, limiting the Wa and Baekje forces’ ability to manuever, drawing them in and then counterattacking. Eventually the Tang ended up destroying so much of the fleet that the remaining Wa ships had no choice but to turn and flee.

This defeat had profound consequences for the region. First and foremost was the fall of Baekje. In addition, Yamato forces pulled back from the continent altogether. Along with those Baekje refugees who had made it with them back to the archipelago they began to build up their islands’ defenses. Baekje engineers were enlisted to design and build fortresses at key points, from Tsushima all the way to the home countries. These fortresses included massive earthworks, some of which can still be seen. In fact, parts of the ancient fortifications on Tsushima would be reused as recently as World War II to create modern defenses and gun placements.

Even the capital was moved. While many of the government offices were possibly operating out of the Toyosaki palace in Naniwa, the royal residence was moved from Asuka up to Ohotsu, on the shores of Lake Biwa. This put it farther inland, and behind a series of mountains and passes that would have provided natural defenses. Fortresses were also set up along the ridgelines leading to the Afumi and Nara basins.

And all of this was being done under a somewhat provisional government. The sovereign, Takara Hime, had passed away at the most inconvenient time—just as the Yamato forces were being deployed across to the peninsula. A funerary boat was sent back to Naniwa, and Naka no Oe took charge of the government. That there was little fanfare perhaps suggests that there wasn’t much that actually changed. Still, it was a few years before the capital in Ohotsu was completed and Naka no Oe formally ascended the throne, becoming known to future generations as Tenji Tennou.

Naka no Oe’s rule may have only formally started in the 660s, but his influence in the government goes all the way back to 645. He assassinated the Soga family heads, and then appears to have been largely responsible for organizing the governmental reforms that led that era to be known as the Taika, or era of great change. He served as Crown Prince under Karu and Takara Hime, and from that office he ensured his supporters were in positions of authority and instituted broad changes across the board.

He continued in this position under the reign of his mother, Takara Hime, and so the transition upon her death was probably more smooth than most. This also explains how things kept running for about three years before he took the throne.

In officially stepping up as sovereign, however, Naka no Oe continued to solidify the work that he had done, focused largely on consolidating power and control over the rest of the archipelago. There were tweaks here and there—perhaps most notably changes to the ranking system, which allowed for a more granular level of control over the stipends and privileges afforded to different individuals as part of the new government. This work was presumably being done with the help of various ministers and of his brother, Ohoama. Ohoama only really shows up in the Chronicle around this time, other than a brief mention of his birth along with a list of other royal progeny of the sovereign known as Jomei Tennou.

We also see the death of the Naidaijin, Nakatomi no Kamatari—and supposedly the head of what would become known as the Fujiwara family. His position as Inner Great Minister was not backfilled, but rather Naka no Oe’s son, Ohotomo, was eventually named as Dajo Daijin, the head minister of the Council of State, the Dajokan, placing a young 20 year old man above the ministers of the left and right and in effective control of the government under his father—though his uncle, Prince Ohoama, maintained his position as Crown Prince.

However, even that wasn’t for long. As Naka no Oe became gravely ill, he began to think of succession. Ohoama, having been warned that something was afoot, offered to retire from his position as Crown Prince and take up religious orders down in Yoshino, theoretically clearing the line of succession and indicating his willingness to let someone else inherit. His actual suggestion was that Naka no Oe turn the government over to his wife, who could act as a regent for Ohotomo. What actually happened, however, was that the movers and shakers in the Council of State pledged their loyalty to the Dajo Daijin, Prince Ohotomo, who was named Crown Prince and ascended the throne when his father passed away.

Here there is a bit of a wobble in the historical record. The Chronicles never mention Prince Ohotomo formally assuming the throne and therefore the Chroniclers never provide him a regnal name. It isn’t until more modern times that we get the name “Kobun Tennou” for his short-lived reign.

And it was short-lived because early on Ohoama raised an army, and after several months of fighting, took the throne for himself. Because the year this happened was known by its sexagenary term as “Jinshin”, often colloquially known as a Water Monkey year, the conflict is known as the Jinshin no Ran. “Ran” can mean disturbance, or chaos, and so is often translated as “Jinshin Disturbance”, “Jinshin Revolution”, or the “Jinshin War”. The entirety of the fighting is given its own chapter in the Chronicles, known as either the first year of Temmu or sometimes as the record of the Jinshin War. This chapter actually shows some stylistic differences with the chapter on Tenji Tennou, just before it, and tells the story of the events slightly differently, in a light generally favorable to Ohoama, who would go on to become Temmu Tennou. As such, while the broad strokes and military actions are likely correct, there are a lot of questions around the details, especially around the motivating factors.

Regardless, what is known is that Ohoama was able to quickly move from his quarters in Yoshino eastward towards Owari and Mino, where he was able to cut off the capital from support and gather troops from the eastern lands. The Court tried to take the Nara Basin—a huge symbolic and strategic point—as well as cut off his supply lines, but these actions were thwarted by those loyal to Ohoama. Attempts to gather troops from the west had mixed results, with several allies of Ohoama resisting the Court—most notably Prince Kurikuma, who at that time was the head of the government presence in Kyushu, where a large number of troops had been stationed to defend against a possible Tang invasion.

Eventually, Ohoama’s troops defeated those of the Court. Ohotomo was killed, and those running the government, including Soga no Akae, Nakatomi no Kane, Soga no Hatayasu, Kose no Hito, and Ki no Ushi, were either executed or exiled.

Ohoama then swept into power. He moved the court back to Asuka—the move to Ohotsu had not been a popular one in the first place—and took up residence in his mother’s old palace, renovating it. It would eventually be known as the Kiyomihara palace. From there Ohoama continued his brother’s reforms, though with his own spin.

First off was a reform to the ceremonies around royal ascension. Taking the existing feast of first fruits, the Niiname-sai, Ohoama made it into a new public and private ceremony known as the Daijo-sai, which is still practiced today upon the elevation of a new sovereign. He reformed the government court rank system and also instituted reforms around the ancient kabane system—the ancient rank system that contained both clan and individual titles. These old kabane titles had certain social cachet, but were otherwise being made obsolete by the new court ranks, which were, at least on paper, based on merit rather than just familial connections. Of course, the truth was that family still mattered, and in many ways the new kabane system of 8 ranks simply merged the reality of the new court with the traditions of the older system.

And this was something of a trend in Ohoama’s reign. The court seems to have taken pains to incorporate more kami-based ritual back into the court, with regular offerings, especially to gods associated with food, harvest, and weather. There is also a clear focus on the shrine at Ise. The Chroniclers claim that Ise was established and important since the time of Mimaki Iribiko, but it is only rarely mentioned, and while its founding story might be tied to that era, the Chroniclers, who appear to have started their work this reign, appear to have done their best to bolster that connection.

As for actual governance, we see another change from the government of Naka no Oe. The former sovereign relied heavily on noble families to run the government, granting them positions of responsibility. In the Ohoama court, however, most of those positions appear to lay dormant. Instead we see copious mention of princes—royal and otherwise—being delegated to do the work of the throne.

Indeed, Ohoama seemed to want to reinstate the majesty of the royal society, including both the royal family, but also others with royal titles as well. Still, there were plenty of ways that the noble families continued to have an influence in various spheres of government, they just weren’t handed the kind of prime ministerial powers that previous generations had achieved.

Within the royal family, itself, Ohoama attempted to head off future succession disputes. He had been through one himself, and history was littered with the violent conflicts that followed on the heels of a sovereign’s death. So Ohoama gathered his family together, to include sons and nephews of consequence, and he had them swear an oath to support each other and the Crown Prince. After doing so, he seems to have utilized them to help run the country, as well.

Of course, we’ve seen how such pledges played out in the past, so we’ll have to wait to see how it all plays out, eventually. I’m sure it will be fine…

Whilst the archipelago was going through all of this transition—from the death of Takara Hime, and then the reign and death of her son, Naka no Oe, along with the Jinshin no Ran that followed-- we have a glimpse of what was happening on the peninsula. Yamato had fortified against a combined Silla-Tang invasion, but it seems they needn’t have done so.

First off, that alliance’s attention was turned northwards, to Goguryeo. With the death of the belligerent tyrant and perpetual-thorn-in-the-side-of-the-Tang-Court, Yeon Gaesomun, the Tang armies were finally able to capture the Goguryeo court. However, for years afterwards they were dealing with rebellions from those who had not gone quite so quietly. And to make matters worse it turns out that these Goguryeo recalcitrants were apparently being funded by none other than Silla, the Tang’s supposed ally.

From the Yamato perspective this manifested, initially, as embassies from both the Tang court and the Silla court. While the content of the embassies’ messages are not fully recorded, we can imagine that both the Tang dynasty and Silla were looking for support. At one point there was a direct request for military support, but Yamato offered a half-hearted reply along the lines of the fact that they didn’t have as many able-bodied men as they once did—not after the fighting in Korea. And that might have even been true.

Either way, the Tang embassies petered out, as the Silla influence came to dominate the embassies and trade more generally. The Tang attempted to push back against Silla, militarily—their alliance now long since dead. Silla took some initial losses, but ultimately was able to push the Tang off of the peninsula, uniting everything from Pyongyang south. North of Pyongyang, though still nominally under Tang dynasty control, a rebel Goguryeo court continued to act as though they were still a going concern. They hitched a ride on Silla ships and traveled to Yamato for regular missions, maintaining diplomatic ties.

As such, Yamato itself relaxed, to a certain extent, its defensive posture—but not entirely. They continued to maintain the fortresses and there were several edicts addressing military preparedness, so as to ensure that Yamato would be ready should anything occur.

And though the missions to the Tang court themselves may have been stymied in this period, it doesn’t mean that Yamato lost interest in continental learning. They had acquired numerous texts, and appear to have been devouring them, as well as generating their own observational data. They were recording a variety of phenomena, some more clearly consequential than others. Some of that was practical, but, in a time where there was very little dividing the natural and the supernatural in the minds of the people, they were just as likely to record a storm or an earthquake as they were the finding of a white or albino animal that is not normally that color. Science, myth, and legend often clashed and intermingled. Regardless, they carried on, figuring out what they could and filling in the gaps where they had to do so.

And I believe that catches us up for the year. If I were to add anything, it would probably be a short note on Ohoama’s wife, Uno no Sarara hime. Uno no Hime is only mentioned occasionally during Ohoama’s reign, and yet those few times are more than many others appear to have been mentioned. She is explicitly said to have traveled with him when he went on campaign, and is said to have been there when he made his prayers to Ise shrine. She was also there when the family was gathered to swear to assist each other in the smooth running of the government.

There is plenty to suggest that, especially with many of the Great Minister roles left empty, that Uno Hime had a much greater role in the administration of the government than is otherwise assumed. This may have also been the case with Naka no Oe’s wife. Both women are mentioned in ways that suggest they were considered to have some amount of political clout and savvy, and had greater agency than one might otherwise conclude. Remember, Takara Hime had twice reigned in her own right, and we aren’t so many generations removed that people wouldn’t know the name of Kashikiya Hime, aka Suiko Tennou. We also know that there was a lot more going on, but the focus of the Chronicles is pretty firmly on the sovereign, and it is only with the greatest of reluctance that the Chroniclers turn that lens on anyone else except the sovereign who was reigning at the time. So I think it is safe to say that Uno likely played a large role in the court, and we will see even more of that in the coming year.

But first, there is going to be more to say about the reign of Ohoama. After all, we aren’t entirely through with his reign. We have only barely touched on the various Buddhist records in the Nihon Shoki, nor some of the various court events, as well as some sign of how the government enforced these new laws and punishments—the Ritsuryo system. Finally, we’ll talk about Ohoama’s dream and vision for a new capital—a permanent capital city unlike anything that had yet been seen. Ohoama would not see that through to completion, but we can talk about what it meant, the first permanent capital city in the archipelago: Fujiwara-kyo.

Until then, I hope that everyone had a wonderful holiday season. As usual, thank you for listening and for all of your support. Thanks also to my lovely spouse, Ellen, for their continued work at helping to edit these episodes!

Remember, if you like what we are doing, please tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

-,- (last checked 30 Nov 2025). 「南海トラフ地震について」. Japan Meteorological Agency. https://www.jma.go.jp/jma/index.html .

Izutsu, Yohei; et al (Last Reviewed 2025). The Kyoto Costume Museum Website. https://www.iz2.or.jp.

Bentley, John R. (2025). Nihon Shoki: The Chronicles of Japan. ISBN 979-8-218634-67-4 pb

Dischner, Matthew Z. (—). “Xuanzang”. The Sogdians: Influencers on the Silk Roads. Online exhibit of Smithsonian’s National Museum of Asian Art. https://sogdians.si.edu/sidebars/xuanzang/ (last accessed 15 March 2025).

M. Meyer, G.W. Kronk. (2025). THE GREAT COMET C/1743 X1: POSSIBLE IDENTIFICATION IN HISTORIC RECORDS OF 1402, 1032, 676, AND 336 (J/OL). Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 2025, 28 (1): 29-49. 2025-04-28. 2025-12-01. https://www.sciengine.com/doi/10.3724/SP.J.140-2807.2025.01.02.

宮崎, 健司. (2025). 地図でスッと頭に入る飛鳥・奈良時代. 株式会社昭文社.

Zhang, F., Ning, C., Scott, A. et al. The genomic origins of the Bronze Age Tarim Basin mummies. Nature 599, 256–261 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04052-7

Bauer, M. (2020). The History of the Fujiwara House: A Study and Annotated Translation of the Tōshi Kaden. Amsterdam University Press.

https://doi.org/10.1017/9781912961191.Wu, Guo. (2020). From Chang'an to Nālandā: The Life and Legacy of the Chinese Buddhist Monk Xuanzang (602?-664) From Chang'an to Nālandā: The Life and Legacy of the Chinese Buddhist Monk Xuanzang (602?-664). Proceedings of the First International Conference on Xuanzang and Silk Road Culture.

Teeuwen, Mark and Breen, John. (2017). A social history of the Ise shrines: divine capital. Bloomsbury Academic.

Duthie, T. (09 Jan. 2014). Man’yōshū and the Imperial Imagination in Early Japan. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004264540

Kim, P., & Shultz, E. J. (2013). The 'Silla annals' of the 'Samguk Sagi'. Gyeonggi-do: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Hansen, V. (2012). The Silk Road: a new history. Oxford ; New York, Oxford University Press.

Kim, P., Shultz, E. J., Kang, H. H. W., & Han'guk Chŏngsin Munhwa Yŏn'guwŏn. (2012). The Koguryo annals of the Samguk sagi. Seongnam-si, Korea: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Beckwith, C.I. (2009) Empires of the Silk Road: A History of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the Present. Princeton University Press, Princeton/Oxford. ISBN 978-0-691-13589-2.

Como, M. (2009). Weaving and binding : immigrant gods and female immortals in ancient Japan. University of Hawaiʻi Press.

Lewis, Mark Edward (2009). China’s Cosmopolitan Empire: The Tang Dynasty. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts / London, England. ISBN 978-0-674-03306-1

McCallum, D. F. (2009). The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Art, Archaeology, and Icons of Seventy-Century Japan. University of Hawai’i Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt6wqtwv

Ooms, H. (2009). Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan: The Tenmu Dynasty, 650-800. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. https://muse.jhu.edu/book/8316.

Kuramoto, Kazuhiro (2007). 壬申の乱. 吉川弘文館. ISBN 978-4-642-06312-8.

Bentley, J. (29 May. 2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047418191.

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Yoshida, Yutaka (2006). “Personal Names, Sogdian i. in Chinese Sources” Encyclopædia Iranica; available online at https://iranicaonline.org/articles/personal-names-sogdian-1-in-chinese-sources (accessed online at 10 February 2025).

Boulnois, Luce (2005). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants. Hong Kong: Odyssey Books & Guides. pp. 311–335. ISBN 962-217-721-2.

Michael, Thomas, PhD. (2005, February 12th). “I-Ching”. Lecture--Smithsonian Residents Associate, Washington, D.C.

Mallory, J. P., & Mair, V. H. (2000). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. London: Thames & Hudson

ed. Minford, John and LAU, Joseph S. M. (2000). “An Anthology of Translations: Classical Chinese Literature: Volume I: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty”. The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong.

Barber, E. J. W. (1999). The mummies of Urumchi. New York, W.W. Norton & Company.

Huang, Alfred (1998) “The Complete I Ching: The definitive translation from the Taoist Master Alfred Huang.”. Lake Book Manufacturing, U.S.

Piggott, Joan R. (1997). The Emergence of Japanese Kingship. Stanford, Calif : Stanford University Press. ISBN9780804728324

Frye, R. N. 1. (1996). The heritage of Central Asia from antiquity to the Turkish expansion. Princeton, Markus Wiener Publishers.

Xuanzang, tr. Li Rongji (1996). The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions. Berkeley, Calif. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.

tr. Bock, Felicia G. (1995) “Classical Learning and Taoist Practices in Early Japan: with a Translation of Books XVI and XX of the Engi-Shiki”. Arizona State University, Tempe, Arizona.

Huili, Yancong, & Li, R. (1995). A Biography of the Tripiṭaka Master of the Great Ci’en Monastery of the Great Tang Dynasty. Berkeley, Calif. Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research.

ed. Mair, Victor H. et al (1994). “The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature”. Columbia University Press, New York.

Major, J. S. (1994). The Trail of Time: Time Measurement with Incense Clocks in East Asia. By Silvio A. Bedini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994. The Journal of Asian Studies, 53(4), 1206–1207. doi:10.2307/2059241

Brown, Rober L.; MacDonnell, Anna M. (1989), "The Pong Tuk Lamp: A Reconsideration". The Journal of the Siam Society, vol. 77, pt. 2, 1989. pp. 9-20.

Lee, K. (1988). A New History of Korea. Translated by E. W. Wagner & E. J. Schutz. Harvard University Press.

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Ellwood, R. S. (1973). The Feast of Kingship: Accession Ceremonies in Ancient Japan. Japan: Sophia University.

Miller, Richard J. (1973). Ancient Japanese Nobility: The Kabane Ranking System. University of California Press. ISBN 0-320-09494-8.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4.

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1.

Nakayama, Shigeru (1969). “A History of Japanese Astronomy: Chinese Background and Western Impact”; Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Werner, E. T. C. (1961). “A Dictionary of Chinese Mythology”. The Julian Press, Inc. Publishers, New York.

Frank, Bernard (1958). “Kata-imi et Kata-tagae: Etude sur les Interdits de direction a l'epoque Heian”. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris.

Asakawa, K. (1903). The Early Institutional Life of Japan: A Study in the Reform of 645 AD. Tokyo Shueisha. Reprint (1963): Paragon Book Reprint Corp., New York, N.Y. 10016

Kaempfer, Engelbert (1727) / tr. BODART-BAILEY, Beatrice M. (1999). “Kaempfer's Japan”. University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu, Hawai'i.

Iryon, (1206-1289) & Ha, Tae Hung & Mintz, Grafton K. (1972). Samguk yusa : legends and history of the three kingdoms of ancient Korea / written by Ilyon ; translated by Tae-Hung Ha [and] Grafton K. Mintz. Seoul : Yonsei University Press