Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we’ll talk about the history of, well, history. Homuda wake is seen as a pivotal figure in many ways, and stands at the head of what is thought to be by some a completely new dynasty. This episode we get into some of that, but we also talk about the actual start of historical record-keeping with the coming of writing to the court, including a court record keeper. Of course, that doesn’t entirely mean that just because they started writing things down everything we have from here on out is a 100% accurate representation of the facts.

One of the things that we don’t exactly know is just when this was happening. Despite the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki being largely in agreement on most of the details, they place the advent of writing at two different points in the late 4th century. The Kojiki claims that the Baekje king at this time was our good friend Chogo, while the Nihon Shoki claims that it was Asin. King Chogo’s reign ended with his death in 375 CE and King Asin reigned from about 392-405, so there is a bit of a gap. It is quite possible that it was even a different sovereign altogether. In the case of the Kojiki, they may have simply been attributing it to the most notable sovereign, the one who first opened relations with Yamato, and who had just started a written record for Baekje through Gao Xing, while in the Nihon Shoki they don’t expressly name a sovereign so much as date this whole thing to a year that, when corrected, would line up with the dates of King Asin. One possible hint in all of this is the mention, in the Nihon Shoki, of Areda Wake as the lead envoy to request Wang’in’s presence. Areda Wake, you may recall from last episode, was one of the generals sent to the peninsula during the Yamato-Baekje campaigns in 369. Either way, they both agree that this was during Homuda Wake’s reign, whenever that actually was and we can probably assume that was some time between the 370s and 405, during which time there was plenty of contact between the archipelago and the peninsula.

The other big thing we talk about in this episode is the advent of horses.

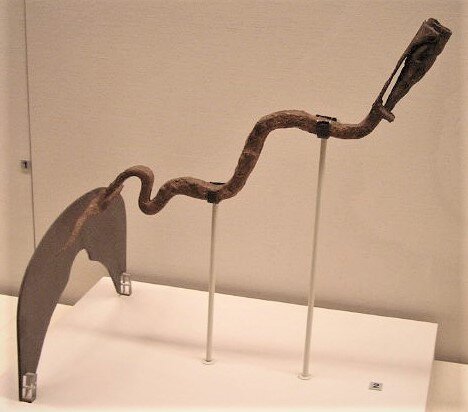

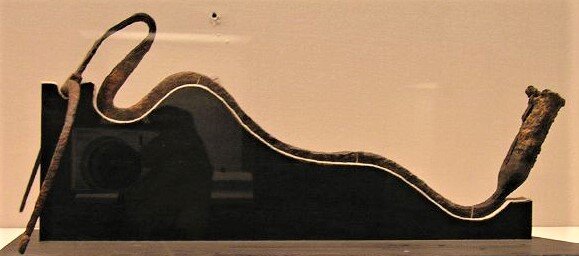

We talk about what a big deal the horse is in the episode, and what we find in the 5th century tombs, so here is a gallery of just a few of the horse items that we find, from haniwa to actual tack.

One more thing—we previously mentioned that Homuda Wake’s name seems to come from something that was later referred to as a “tomo”. That appears to be this item shown on this 6th century haniwa warrior. There are also examples that we have in the Shōsōin repository from the 8th century. Those are made of a stuffed leather. It is unclear to me exactly how they were used—they seem extremely bulky, and they aren’t used in any modern tradition that I am aware of. Nonetheless, one could get an idea of how a fatty growth on the arm could be seen as something similar, though I still am not sure about calling them “homuda”.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is episode 43: Finally, Some Real History (and Some Horses Too).

Alright, so I know I keep saying we are almost there. We are almost to real historical stuff. You know, stuff that was written down, so we have some idea that it actually happened and we aren’t just dealing with oral history. And I think we are finally there. Well, sort of. Okay, let me explain.

This episode we are finally talking about Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, the first sovereign traditionally considered truly historical in that it was during his reign that the court started to keep records. Or at least that’s what we are told. You see, we aren’t quite sure because those particular records no longer exist, and where they were incorporated into the Chronicles they aren’t exactly highlighted as such AND there was still plenty of oral history going on at the same time.

You know, let me start back at the beginning. Just know that we are going to talk about several things this episode. Homuda Wake is something of an interesting and pivotal figure in this period, and we’ll talk about why that is, including some talk about the 20th century scholarship about him, and how that has affected our current views of this reign. We’ll also discuss some of the big things that happened during this time—primarily the advent of record-keeping, as I already mentioned, but also the first evidence of horses coming to the archipelago.

But first, let’s recap where we are. Supposedly, we are somewhere at the end of the 4th century. Probably some time after 371—possibly later, though it could be earlier—with the previous sovereign-slash-regent Tarashi Hime’s death tied to that of Queen Himiko, the exact timing is confused, but we are still generally assuming that the dating in the Nihon Shoki is about 120 years or so off of what was actually happening.

Tarashi Hime’s death finally put her son, Homuda Wake, firmly in the driver’s seat. Whether or not he was part of a ruling pair before this, he was certainly the one handling things from here on out. And he was inheriting the throne at a highly dynamic period. While I’m not quite sure there was an archipelago spanning government—local countries were probably still operating under their own systems—the influence of Yamato and the surrounding area, as well as the keyhole tomb culture in general, seem to have gained prominence, and they had relations—friendly and otherwise—with at least two of the more powerful kingdoms on the peninsula, Baekje and Silla.

From here on out, though as I said, we supposedly start to get actual written accounts that were included into the Chronicles, the dates for many things are still quite sus. The Chronicles from this point were probably a combination of information from written sources from the peninsula and the archipelago as well as various oral histories that were handed down separately. We see a lot of poetry, written in a style of Man’yogana, that is using the Sinitic, or Kanji, characters for their sound and very deliberately reproducing the Japanese poetry styles that would become popular later on. We also see various accounts from the continent that may or may not have lined up appropriately with things happening in the archipelago.

Time wise, you have two major reigns coming up—Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, and his son, Oho Sazaki, aka Nintoku Tennou. Once again it is somewhat difficult to tell if they actually reigned separately—heck, some people even claim they may have been the same person! Either way, I suspect both reigns were considerably shorter than they are written, especially when you look at other reigns that are only a handful of years. Remember, the historians needed to “find” a couple of 60 year cycles in all of this, to make the math work out according to plan.

One more thing about this period is that there seems to be a bit of a disconnect between our continental and archipelagic sources. Continental sources talk about the fighting and conflict on the peninsula at this time, while the Japanese chronicles focus on more inward matters. And so while there may be some hints of where the two come together, it isn’t at all clear every time.

So where do we get started? Well, we already know a few things about Homuda Wake. For one thing, he was miraculously carried in his mother’s womb for up to three years, if the Nihon Shoki is to be believed, and his name supposedly comes from a growth on his arm that looked like a “Homuda”, or an archer’s wrist-guard. Of course, he also went up to Kehi, at Tsunoga Bay, and exchanged names with the kami of that area. But beyond that, we know very little.

We know that the Nihon Shoki dating is off, and he probably wasn’t in his 69th year when his mother died and he came to the throne. Beyond that there isn’t a lot we can be sure of.

He does seem to have many wives and a fair number of children, at least according to the stories, though whether they are all his or not we can’t be entirely sure, and the kofun attributed to him, Konda yama Kofun, in modern Ohosaka—which may or may not be his, mind you—is definitely in the kingly category in terms of size.

Perhaps most relevant for us to keep in mind that is that Homuda Wake is is considered by many to be at a turning point, and he is placed at the head of the “Middle Dynasty” or the “Kawachi Dynasty”, a potentially new group of regents, despite the orthodox view of an unbroken lineage. Along with the influx of various technologies from the continent, this makes this a very interesting period. I’ve made mention of this before, here and there, but I would like to talk about what this all means.

The Japanese Imperial Household Agency maintains the orthodox view expressed in the Chronicles that the current emperor can trace an unbroken lineage all the way back to the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu Ohokami. That doesn’t mean that every sovereign is necessarily the direct descendant of the previous one—we see brothers and cousins and nephews inheriting the throne, instead—but they are all part of that lineage with a direct tie back to the lineage of the Sun Goddess herself. This is the official line coming out in the 8th century that can be seen in all of the various Chronicles, to include the Kujiki, the Kojiki, and the Nihon Shoki. Even if there are some things that may be fantastical legends, this view holds that the lineage is basically correct, even if some of the details might be a little bit fuzzy.

This orthodox view was largely maintained up through the end of WWII in the early 20th century. There may have been those who questioned parts of the lineage, and even those who considered that many of the details were added or lifespans enhanced in order to extend the lineage back to around 663 BCE, but even though they may have questioned some of it, the orthodox view still held as true that the imperial lineage traced back to Amaterasu Ohokami, at least.

In the early 20th century, a right-wing nationalist fervor overtook Japan, and much of it centered around the concept of Kokutai, the government of the state, based on the idea of a Heavenly-descended Imperial Line. I won’t try to pass myself off as a student of these modern times, but suffice it to say that there was a clear party line on what constituted the Japanese state and the Emperor was at its head. Proponents of this view set themselves up against what they saw as Marxist and left-wing Socialists, whom they believed would destroy the character of the country. In such a heated political climate, discussion of the Imperial lineage became more than just a matter of history.

Enter one Tsuda Soukichi. In the early 1900s he wrote up his belief that much of the lives of the first fourteen sovereigns—so up through and even including Okinaga Tarashi Hime—was fictional. While some of the stories may have come from actual incidents, Tsuda claimed that the overall history was written merely to support the central raison d’etre of the Chronicles—codifying the divine lineage of the Imperial line. For the most part this was an academic discussion and seems to have stayed in academic circles, and I don’t know that he saw his own view as particularly radical, but in 1942 he was actually taken to court for his views, accused of profaning the imperial house. He was actually sentenced to 3 months in prison, but was later pardoned. All because his theories questioned what some considered the foundation of the Imperial Household.

After the war, there was a much greater freedom to investigate the origins of Japan and the Emperor, though the imperial household agency continues to control certain aspects tightly to maintain the dignity of the imperial family. Still, many theories have flourished, often building off of Professor Tsuda’s work.

For example, moving beyond the idea that the first fourteen sovereigns are purely fictional, there is some thought that the earliest sovereigns may have simply been unrelated lords of various areas in and around the Nara basin, though I tend to agree that for those first nine sovereigns there is very little evidence of their existence at all.

Another scholar, Mizuno Yu, who studied at Waseda University around the same time that Tsuda was teaching there would go ahead and divide the sovereigns into three dynasties, suggesting even further that while some of the sovereigns may have existed, they were not actually linked hereditarily. Under Mizuno’s system, the first nine sovereigns were considered completely fictional, while the emperors from Mimaki Iribiko through Tarashi Nakatsu Hiko are considered part of the ancient dynasty, sometimes called the “Miwa” court, due to the location of the court at the foot of Mt. Miwa in the southeast corner of the Nara Basin. The site of this court was attested to in the Nihon Shoki, and of course there were numerous kofun and the holy mountain of Miwa itself, but there was still some doubt about whether there had actually been any kind of a court here until 2009, when an excavation found an extremely large structure, thought to be a palace or ritual center, which dated from about the 3rd century, which would seem to confirm the Chronicle’s account, though the dating was clearly off. This dynasty is sometimes referred to as the “Iri-“ dynasty due to the prevalence of the term in various names. For example, Mimaki IRI-biko and Ikume IRI-biko.

Mizuno also included the Tarashi dynasty in this same general category, although there seems to be more support for the Mimaki and Ikume Iribiko than for the various Tarashi’s, including Oho Tarashi Hiko, Waka Tarashi Hiko, Tarashi Naka tsu Hiko, and Okinaga Tarashi Hime. While Mimaki and Ikume are assumed to be actual names, the other rulers of this ancient period seem to be marked with titles, with the exception of the name “Okinaga”, and so there are much greater doubts about their actual existence.

Mizuno’s next dynasty was the Middle dynasty, sometimes called the Kawachi court and that started with our current subject, Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, and continues until the 25th sovereign, wo-Hatsuse no Waka Sazaki no Mikoto, aka Buretsu Tennou. His successor, Wohodo, aka Keitai Tennou, was not directly related to him. In fact, Wohodo’s lineage goes separately back some five generations to our current sovereign, Homuda Wake. From Wohodo to the current Emperor, Mizuno considered that the New Dynasty.

We do know that the center of building for the giant, kingly kofun transitioned around this time from the Nara Basin out to the country of Kawachi, in the area of modern Ohosaka. Large tombs were built in this area until the time of Wohodo, aka Keitai Tennou, in the early 6th century. Together they are known as the Furuichi and Mozu tumulus groups. They are the most dramatic evidence of the court having moved to this area around this time, and it includes the largest of the keyhole shaped tombs, Daisen Kofun. If that name sounds familiar it has been in the news of late as they have allowed some very basic excavations to take place recently on the outside of the tomb as part of the necessary upkeep. This tomb is actually said to belong to Homuda Wake’s successor, and is an indication of the power of the early Kawachi court.

Now here’s the thing about this and Mizuno Yu’s theory: He not only noted that the courts had moved, but he also suggested that these three dynasties weren’t actually related to each other despite what the Chronicles say. Or at least, not significantly. According to Mizuno, the Chroniclers pasted the various dynasties together into a single lineage to support the legitimacy of the current sovereigns in the 8th century, but prior to that, these dynasties may have actually descended from separate groups of local rulers, who may have had varying degrees of control, though generally ruling from the modern Kinai region, around the country of Yamato. The 6th century Wohodo’s own tenuous link to Homuda Wake may be little more than a genealogical fiction designed to support his legitimacy and connect him back to an older dynasty, and likewise the Tarashi lineage may have been little more than a bridge from the Iribikos up to Homuda Wake.

As it stands, there is still plenty of debate and conjecture over Homuda Wake. Some conflate him and his successor, Oho Sazaki, aka Nintoku Tennou, and others would suggest that the events of his mother’s regency were actually his, and that her existence is largely just a correction in the Chronicles for Queen Himiko.

If I were to suggest anything to take a way from this it is to understand that there is a lot of evidence that the story of a single, unbroken, royal lineage is likely a fiction. Rather, there were several different dynasties that supplied sovereigns at different times. We already know that the chronology is demonstrably incorrect, to the point that some would write it off altogether.

So what is it about Homuda Wake’s reign that makes all of this relevant? Why do these theories all seem to come to a head right here?

Well, that probably has to do with one of the more significant events attributed to Homuda Wake’s reign, and although they can’t agree on the exact details, both the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki do agree on one thing: This was the first reign whose events were, in some form or fashion, written down. And not only were they written down, but they were written down by the court itself. I can’t stress how important this is to us. Up to this point, our assumption has been that we only had the oral histories to go on, which were then written down at a later point. Now it looks like we have one of the most important events in the history of the archipelago—writing had come to Japan.

This event is recorded in both the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki in such a similar manner that it certainly seems that they were pulling from the same source for how it came to be. They do have differences, and I’ll get to that in a second, but for the most part it is the same. So the stories go, the King of Baekje sent a pair of horses, along with an envoy, who is named in both Chronicles as either Ajikki or Achikishi. The horses were stabled on the slopes of Karu, and Ajikki was given charge of their care and feeding—apparently this was a long-term posting for Ajikki.

Now the horses are certainly interesting—this is likely the beginning of a long culture of horse cultivation in the islands, built off of the peninsular traditions—but there was something more interesting to the people of the time and this is that Ajikki had another skill that the court wanted to cultivate beyond his animal husbandry skills. You see, unlike many others in Yamato at that time, Ajikki could read, and because of that, the young Crown Prince asked him to become his tutor, so that the Crown Prince could learn to read the Classics himself.

Now I doubt that writing was completely new to the people of Yamato, but it is unclear just what sort of grasp they had on the skill. After all, this wasn’t just as simple as learning an alphabet and then learning how to write words with those letters. Literary culture in east Asia at this time relied on Sinitic writing—that is to say the ancient literary Chinese. Of course, Sinitic languages are from a completely different linguistic family than Japonic or even Koreanic. Grammar and word order, in particular, are different. Sinitic actually has more in common with Tibetan than with the languages of the Korean peninsula or the Japanese archipelago. So that means that it wasn’t enough to learn individual characters, or logograms, but you had to learn an entirely new language.

Speaking of the logograms, I’d like to touch on one misconception. Many people consider Chinese to be made up of pictograms, where a picture represents a given word. The issue is that Chinese, or Sinitic, characters aren’t actually pictures. There are certainly symbols that represent particular things, like trees or people, and a direct link can be seen between those characters and earlier pictures. However, by the time of the 4th century, the characters had grown much more complex. They contained symbols with meaning, but also symbols that were used more for the sound they made, and still other symbols represented more abstract concepts. Referring to them as logograms better emphasizes their actual use. Each character, often made up of various parts, represents a single word, concept, or morpheme, and are pronounced as a single syllable.

Now there is evidence of writing in the archipelago from an early date. For example, we have inscriptions on bronze mirrors from at least the start of the Kofun period, if not earlier, and of course the seven branched sword, which had come over from Baekje in the latter half of the 4th century. We also have a few examples of what may be writing on pottery, though usually that is just a character here and there. Most of this writing, however, either came from the continent or it was more decorative or even performative—it demonstrated a certain level of culture and sophistication, but it wasn’t necessary for understanding the meaning. It may have also had a kind of magico-symbolic quality. After all, in many places the idea that you can put ideas into sound and then inscribe those thoughts onto things is really remarkable in a way that those of us in the Computer Age might not always consider. I’m reminded of the various written prayers for the Dead included with the mummies of Egypt, as well as the Tibetan prayer wheels, where the written words stand in for the mantras and prayers of those who turn them round.

But in the 4th century, Yamato was prepared to take the next step. It was more than just performative—this was also basically a request to learn more about the classics of continental literature, such as Confucius and Laozi. Homuda Wake asked Ajikki if there was any one who could teach him and his court how to read the Classics as well. Ajikki, though literate himself, demurred and recommended another Baekje scholar known variously as Wanikishi or perhaps Wang’in.

We don’t know much about Wang’in. The name certainly strikes me as Sinic, though that could just be an artifact of how the name has come down to us. Most likely, if he wasn’t an immigrant to Baekje from the continent, he may have been a descendant of the administrators who had served the Han commanderies in the Korean Peninsula. Either way, he knew the art of writing and could teach it, and so Homuda Wake sent a request to Baekje to send Wang’in over.

With his arrival at the court, Wang’in not only started to teach writing to others, but he also started to chronicle the history of the court—or so we are told. There is no extant evidence of his chronicle, and nothing that I have seen to indicate whether a particular event came from his records or from oral history, which no doubt continued as another source of lore and memory. I mean, it wasn’t like people just stopped telling stories, and even in the reign of Oama in the 8th century the court was still commissioning storytellers to recount history at court.

Since there were records being kept and written down, many consider Homuda Wake to be the first truly historical sovereign, even if we aren’t sure how much of that history is accurate. The point is that for the first time the Yamato court was starting to write out its own records and keep its own annals.

In fact, even the character of the Chronicles themselves, written in the 8th century, would still have elements that link their literary tradition to that of Baekje, and various scholars have drawn a connection between the formulation of the Baekje Annals, as passed down in the Samguk Sagi and elsewhere, and the formulation of Japan’s own chronicles.

Beyond just keeping a record of things, though, writing would also bring other benefits to the archipelago. For one thing, once literacy could be spread, it would increase communication. No longer would you have to rely on the memory of a messenger to relay information, but rules, laws, and edicts could be written down and communicated directly. Likewise, information from the provinces could easily be sent back to the capital. In this way, it was a technological advancement for the state itself, and may have helped to solidify the archipelago even further along its march to status as a unified kingdom.

On top of that, it opened the doors to a host of continental ideas and philosophy. While there is evidence of ideas that entered previously through contact with the continent, being able to read and write would open up so much more to consider. Of course, this would also bring some amount of turmoil, as the indigenous ideas and philosophy that had grown up on the archipelago came into potential conflict with ideas and philosophies from the continent—but that is all still a ways out at this point.

Of course, all of this talk about writing—which is a huge step, by the way, don’t get me wrong—and we didn’t even touch on the other big thing that happened. In fact, it almost got swept aside for all of the literary geekiness. The second big thing that happened in this exchange was that this is the first recorded instance of Japan getting horses.

I know we’ve mentioned this in past episodes. In the discussion of Yamato Takeru, for instance, they talk about how the bridges and mountain pathways through the Japan Alps were often so narrow that a horse wouldn’t be able to make it, but that was before we have evidence of horses or of horsemanship on the archipelago. Up to this point we had seen domestication of some animals, including pigs, but there was scant evidence of horses. There is perhaps evidence of some horse remains from before the Kofun period, but what I’ve seen suggests that there is still a lot of doubt over those finds. And most of the time travel has been via boat, using the sea lanes to cross from one point of the land to another. And horses weren’t exactly needed for rice cultivation—cattle are actually much more useful in that capacity.

But here we have at least two horses given by Baekje and maintained in stables of some sort. The fact that Ajikki, the envoy who brought them, was also there to see to their care and feeding suggests that there weren’t people in the archipelago who already had the knowledge and skills required for horse husbandry.

As a gift from Baekje, this seems to have been not uncommon. Baekje is also recorded as providing a gift of horses to Silla in the Samguk Sagi. Furthermore, if the nobility of Baekje really did descend from the Buyeo people then it was likely that horse culture was a big part of their ethnic identity, and so I have no reason not to believe that horses would have been a suitable and not uncommon gift to other state leaders.

By the way, there is another theory of how horses came to the islands. This theory, known as the “Horse-Rider Theory” is one we’ve touched on before. It claims that the horses came with an invasion force from the Peninsula—likely led by the Buyeo descended nobility of Baekje, who then put their own descendant, Homuda Wake, on the throne. I’ve already mentioned that this theory is accepted about as well as the second Highlander movie, at least these days, but you still see it pop up now and again, and since we already talked about Tsuda and Mizuno we may as well touch on this as well, since it was formulated around the same time and derived from some of the same scholarly lines of questioning.

You see, following on behind Tsuda Soukichi’s work describing many of the earlier sovereigns in the Chronicles as fictional, and while Mizuno Yu was still laying out his ideas for breaking the royal lineage into separate dynasties, another professor, Egami Namio, published his theory, known as “The Horse-Rider Theory” that similarly questioned the lineage as written, though it had a much more radical concept.

Now, I don’t really want to get too much into the politics in Japan post World War II, but there was something of an explosion of ideas as previously taboo areas of discussion were suddenly opened up for debate. There had also been a lot of archaeological research being carried out during the occupation of the peninsula. Egami Namio’s theory certainly combines both of these, I’d say.

Professor Egami looked at the assembly of horse equipment and armor that seems to typify burials from the 5th century onward, which has many ties with the material culture of the peninsula, and he proposed that there must have been some event to create such a rapid change. Why would these assemblages suddenly show up in kofun from this date onward? To add to that, you have several narratives of ancient sovereigns marching armed forces in from the west, from Kyushu along the Inland Sea Route. First, there is Iware Biko’s march east when he conquered the Yamato basin, and then Okinaga Tarashi Hime traveling east and defeating the forces of Princes Kakosaka and Oshikuma to put her son, Homuda Wake, on the throne. On top of that were the connections between Okinaga Tarashi Hime and Homuda Wake with Kehi and the so-called Silla prince, also known as the kami Ame no Hiboko. Professor Egami suggested that these were all stories of conquest from the Korean Peninsula, suggesting that the Buyeo nobility of Baekje were the actual founders of the Middle Dynasty. According to this theory, the lack of horses in the archipelago made them an easy target for the horse-riding warriors from the peninsula.

Archaeologists have since shown that the increase in horse assemblages in the archipelago can be explained through the natural acquisition of horses from the continent, and it doesn’t otherwise demonstrate a wholesale replacement of local material culture that would be expected with an invasion as suggested.

It should probably come as no surprise that certain Korean scholars have latched on to this idea, and though it has largely been disproven, it still comes up now and again.

Also, even though we don’t see a large invasion from the peninsula, we do see a number of artifacts and the Chronicles definitely seem to demonstrate more and more people from Baekje, Silla, and Kara arriving—willingly or not—in the archipelago. It is also quite possible that Homuda Wake’s own lineage included peninsular nobility—perhaps nobility that was erased in favor of a connection to the previous Iri- dynasty.

Now however they first came to the archipelago, the usefulness of the horse was quickly recognized and while the horse-rider invasion theory of Egami Namio may go a bit too far, there certainly was an increase in horse trappings found in Kofun era tumuli from the 5th century onwards, as well as more armor and weapons. Furthermore, I’m sure you won’t be surprised to know that much of what we find in the tombs matches up with continental fashion and technology, right down to the banner pole holders that would attach to the rear of the saddles. It is quite clear that it wasn’t simply horses that were brought over, but the material culture of equestrianism as well.

Of course, Japan isn’t exactly built for horses. 70% of the archipelago is made up of forested, mountainous terrain—hardly the flat plains of the steppes where Eurasian horse-riding had begun. Much of the flat land that they did have was given over to agriculture in one way or another, and you didn’t exactly want horses stomping on all of the young rice plants, did you?

And yet the horse would come to feature prominently in Japan. Even in the Age of the Gods, on the plain of Takama no Hara, you may recall that it was a colt, a young horse, that Susanowo had flayed and sent flying through the roof of Amaterasu’s weaving hall. Later, various areas would become known for their horses, and in the Kantou region the marshy islands would actually provide natural corrals where they could raise horses of exceptional quality. The use of the horse and the bow, perhaps influenced by further immigrations from the Eurasian continent, would form the basis of the early warriors who would become known as the samurai. Despite a modern view of the samurai as a warrior with a sword, the original connotation was a that of Kyuba-no-Michi: The way of the horse and bow. Even today, you can still witness the art of yabusame, or horsed archery, at various festivals around Japan.

These horses, though, were not, perhaps, the horses you might be thinking of. Many people today think of a horse and imagine something like a thoroughbred—tall and fast. In truth, the horses of Korea an Japan, at least before modern times, were more closely related to their ancestors on the Mongolian steps, and were probably closer to what we would classify as a pony, though that distinction—pony v. horse—is much more of a European classification rather than an Asian one. In Japan, they were all classified as Ma or Uma—horse.

These early breeds were probably shorter and stockier than you might otherwise imagine. The truth is, it is hard to find these ancient breeds today, and most films and even practitioners of traditional arts like Yabusame tend to use more modern breeds. But the shorter and stockier breeds had several advantages.

For one, they tended to be stronger and have greater endurance. Shorter legs would also make them better at navigating the mountain trails and similarly variable terrain. I’ve even heard it said that their gait would also provide a smoother platform, more suitable to a horseback archery, though I don’t have personal experience to confirm.

Either way, the horse would be a huge benefit to the state of Yamato. Not only would it provide a new military tool and advantage in battle, but it also allowed for faster communication. Sure, the boats they used were great for getting around via the water, but horses were much faster on land. Horses could travel 50 to 80 miles in a day. While there are certainly people who can walk 40 miles a day and even runners who have run much more—the world record is over 150 miles in a day—most people are probably in the range of about 20-30 miles in an 8 hour period. Furthermore, by taking a horse, you arrive rested, and with multiple horses you can do even more. This would have been a huge benefit in connecting up the various parts of Japan—at least across the larger islands of Honshu and Kyushu, and even Shikoku.

So there you have it. We’ll go into more details over the next few episodes, but if I were to capture the highlights of Homuda Wake’s reign, I’d say this is it. First off, he’s a pivotal figure in the dynastic succession, and although there were some 10 other sovereigns after him, the new dynasty after that would be linked not to any of his descendants, but rather all the way back to Homuda Wake himself, which does strengthen the case that they may have been a new dynasty altogether. Furthermore, this period in Japanese history would see the advent of writing as well as the horse, two technical innovations that would prove hugely important to the development of Yamato as a whole.

In the next few episodes we’ll deal with some of the other events in the Chronicles, as well as some of the events not covered there, such as the those inscribed on the famous Gwangaetto Stele, a fascinating and, as per usual, controversial source of information.

So, until next time, thank you for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate through our KoFi site, kofi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the link over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode. Questions or comments? Feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page.

That’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Kim, P., Shultz, E. J., Kang, H. H. W., & Han'guk Chŏngsin Munhwa Yŏn'guwŏn. (2012). The Koguryo annals of the Samguk sagi. Seongnam-si, Korea: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1