Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode sees the end of the reign of Homuda Wake, and a little glimpse into the future as well. When talking about history, there is always something of a pull between trying to tell the story of the particularly time period you are looking at but also looking across the years at the influence those events had. Since almost all of history is basically one giant spoiler alert for everything up to the present, it is easy to see things as inevitable, much in the same way that we see our now as an almost ever-present Now and assume that things will always be as they are at this moment. There are so many things that don’t get any attention unless they are connected to something else.

And this episode we do a little of both. We’ll try to look at things in the context of the late 4th and early 5th centuries, but we will also take a peek into the future, particularly in regards to Homuda Wake and his connection with an important god of war whose cult will play an important role in future.

In this blogpost, we’ll dig in a little past the narrative covered in the podcast. We’ll provide some of the individuals involved, but also some of the details that just didn’t make it into the podcast itself this time around. So let’s get started.

Who’s who?

Ajikki (阿直岐)

The Baekje subject who was sent over to Yamato with the tribute of two horses in 404. He helped care for them and teach the Wa what they should do. We are also told that he could read and write and he actually became the tutor to the Crown Prince, Uji no Waki Iratsuko. He is said to be the ancestor the Atogi (Ajikki) scribes.

Wang’in/Wani (王仁)

Baekje scholar sent to Yamato in the year 405. It is thought that he may have been an ethnic Han scholar, descended from those scribes and scholars who supported the Han Commanderies in the 4th century, or possibly even from somewhere across the Yellow Sea. As soon as he arrived in the archipelago he took over Uji no Waki Iratsuko’s education.

Takuso (卓素)

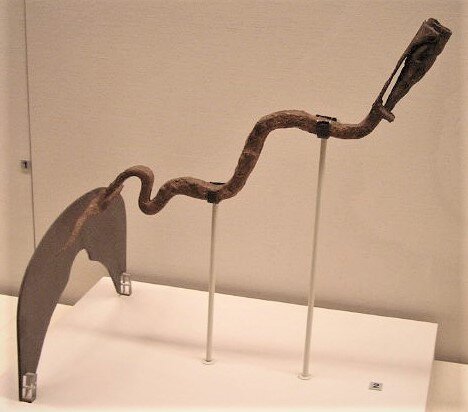

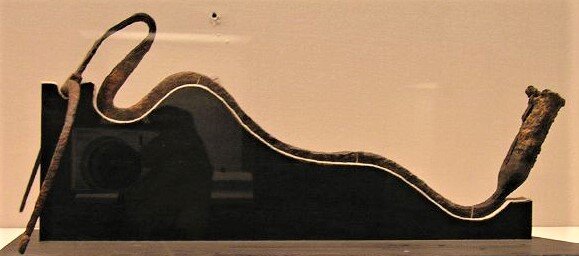

Mentioned in the Kojiki as a smith from Kara who was sent over by the Baekje. The Kara region seems to have long been known for smiths and iron, at least in the archipelago, and was probably where much of Yamato’s early iron products came from. This may explain, somewhat, the similarity of arms and armour between the two regions.

Susukori (須須許理), aka Nipo (仁番)

Mentioned in the Kojiki as a brewer sent over by the Baekje king along with or shortly after Takuso. He apparently made quite the brew for the sovereign and his court, which had Homuda Wake stumbling home. In the podcast we talk about a particular proverb, or kotowaza, that comes from this episode:

堅石避醉人也 ー> 堅石(かたしわ)も醉人(えいびと)を避(さ)く

Katashiwa mo Eibito wo Saku -> Even a solid stone avoids a drunkard.

Maketsu (眞毛津)

Seamstress (縫衣工女) sent over by the King of Baekje in 404 to the Yamato court. She is claimed as the ancestor of the seamstresses of Kume.

Saiso (西素)

A weaver of Kure (呉服 - see below) whom the Kojiki tells us came over with the smith Takuso, sent by the King of Baekje. The Nihon Shoki gives a more detailed account of how weaving came from Kure, however.

Achi no Omi (阿知使主) , Tsuga no Omi (都加使主), and the Weavers of Kure

A father and son who came over with members of the “17 Districts” (十七県). We aren’t exactly sure where they came from, but it is said that they started the Aya clan of Yamato (倭漢), where “Aya” uses the character for the Han dyansty (漢). They would eventually head back to the continent and bring back four weavers of Kure with them.

A map of northern China around 406, during the 16 Kingdoms period. YOu can see a few of the kingdoms that were competing and vying for power at this time. Map by SY, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Regarding the 17 districts, I wonder if this is referencing some of the many divisions in the north of what is today the modern country of China. Though this period is called the “16 Kingdoms” period, those kingdoms were constantly shifting. Even the specific count seems to depend on what gets counted, with the name “16 Kingdoms Period” coming in around the mid-6th century. While I’m not sure of the accuracy of the specific boundaries, I think the map here, taken from Wikipedia, does a decent job of showing the confusion around the time that Achi and Tsuga would have been traveling.

Also, I’d note that the “Omi” here (使主) is interesting to me. Usually the kabane of “Omi”, which usually indicates either a minister or minister-level clan, uses the kanji for “minister”: 臣. In this case, though, they use two kanji, the first of which is often found to indicate “messengers” or “envoys”, and the second is “lord” or “master”. A more intuitive reading might be “tsukahi-nushi”, but universally it seems that “Omi” is the given reading. Dictionaries note that this is a kabane that is regularly found with foreigners. It is not uncommon to find titles that are similar in Japanese, but that use different kanji to differentiate their exact meaning.

To get to Kure, Achi and Tsuga are given two guides. Their names are Kure Ha (久礼波) and Kure Shi (久礼志). The meaning would seem to be clear, and yet their names are not spelled with the character for “Kure” (呉) used for the country.

Finally, we are actually given names for the four weavers that Achi and Tsuda are said to have brought back. They are:

Ye Hime (兄媛) - Elder Lady

Oto Hime (弟媛) - Younger Lady

Kure Hatori (呉織) - Weaver of Kure (aka Wu)

Ana Hatori (穴織) - Weaver of Holes

As you might notice, these names are not exactly informative. Two of them are little more than mentions of birth order—there is even another Ye Hime mentioned elsewhere in Homuda Wake’s own reign—and “Weaver of Kure” sounds purely descriptive. “Ana Hatori” is the only one that doesn’t immediately come to mind as an obvious place name, and yet who knows. There are places such as “Ara” on the peninsula—an “Ana” wouldn’t seem too far off. On a truly far stretch I could possibly draw a connection between the story of Amaterasu and the Heavenly Rock Cave, but that is a bit too far at this point, I think. Notably, there is nothing close to the name “Saiso”, given in the Kojiki.

King Jeonji of Baekje (腆支 / 直支)

Prince (and eventually King) of Baekje. He reigned from 405 to either 415 (the date given in the Nihon Shoki) or 420 (the date given in the Baekje records in the Samguk Sagi). His name is most popularly known as Jeonji (腆支), but is also recognized as Jikji (直支), though Aston posits that this later name is taken from the name of Ajikki, and is a mistake. The Samguk Sagi seems to also claim that “Jikji” is another name, but given its dating it is always possible that for some of these entries they were consulting the Japanese chronicles—though if that were the case I would expect more consistency between them on certain issues, to be honest.

Speaking of, the death of King Jeonji is odd for its disagreement between the sources. In large part, we can match up the sexagesimal dates between the Samguk Sagi records and the Nihon Shoki, at least when the same record exists. Occasionally they might be a year off, which could be explained by when they leave one court and eventually arrive at another. But in this case there are at least 5 years difference between the sources. So which one is correct?

On the one hand, we might assume that the Samguk Sagi is correct since it is the peninsular source. However, it was also written much later, compiled from earlier histories which, as far as I am aware, are no longer extant. The Nihon Shoki was written closer to the events—though still centuries out, and the compilers also appear to have had access to annals specifically from Baekje.

Personally, I suspect that the Nihon Shoki may be right, in this instance, or at least closer to the truth, and they may be in good company. Dr. Jonathan Best, in A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, notes that there is a record for Emperor An of the Eastern Jin (晉安帝), who, in 416, sent an envoy to bestow various titles on the King of Baekje. This shows up in the Nan Shi (南史) and the Song Shu (宋書 - compiled 492-493), where they refer to this king as “餘映” (Yú Ying in Pinyin or Yeo Yeong in modern Korean). Later, in 420, Yeo Yeong is given a new title by the Eastern Jin court, and in 424 that same King, King Yeo Yeong, is said to have sent an envoy to the court of Liu Song.

Now if the Nihon Shoki is correct, it is possible that the king known to the Eastern Jin as Yeo Yeong was Guisin, and perhaps 420 was the year that he attained his majority and even started ruling by himself, which could explain why the Eastern Jin bestowed him with a new title, celebrating his changed status. If, however, this was King Jeonji, as the Samguk Sagi claims, then that envoy arriving in 424 must have somehow been sent at least 4 years earlier, or else we get another contradiction.

My suspicion is that later Baekje records cleaned things up, so that Guisin’s reign began upon him attaining the age of majority, possibly overlooking or sweeping away a potentially embarrassing incident involving Mong Manchi, for whatever reason—either because he just wasn’t considered that important or because the story is less than flattering for the Baekje royal house.

Prince Hunhae of Baekje (訓解)

As the brother of King Asin, Hunhae was the uncle to Jeonji, and upon Asin’s death, Hunhae took the throne of Baekje, reportedly holding it until Jeonji returned, at least according to the Samguk Sagi. However, he was killed by Asin’s youngest brother, Jeomnye, who then usurped the throne. One has to wonder whether or not Hunhae actually had intended to hold the throne for Jeonji, or if he was just another claimant to the throne, despite the noble intentions ascribed to him.

Prince Jeomnye [Jeoprye?] of Bakeje (蝶禮)

Youngest brother of King Asin who killed Prince Hunhae and usurped the throne. Because of this, Prince Jeonji held off his return, holing up on an island with 100 Wa troops. Eventually the people overthrew him and welcomed Jeonji back. Or at least that is what the official records tell us.

King Guisin of Bakeje (久爾辛)

Son and heir to King Jeonji of Baekje. He was apparently too young to rule when he came to the throne, and Mong Manchi seems to have acted as a regent, at least according to the Nihon Shoki. The Baekje Annals of the Samguk Sagi ignore this altogether, which may partly account for why his reign starts many years later in peninsular chronicles.

Mong Manchi (木満致)

Mong Manchi is the son of the general Mong Nageunja (木羅斤資f) (or possibly Mongna Geunja? Given the names, the former is probably correct, though Aston had it in the latter form) and a Silla woman. He seems to have been a lord or even king in Nimna (任那) one of the states of Kara (加羅). When King Jeonji of Baekje died, the Nihon Shoki claims that he took over the administration of that state. The Japanese record claims that Mong Manchi had an affair—or at least improper relations—with the Queen Mother, and so he was recalled by Yamato. The section of the Baekje chronicle claims that he was recalled because of his violence. Of course, there remains a question: what power did Yamato have to recall him in the first place?

Continental Clans

There are three clans, or uji, that come up this reign, and I want to talk briefly about them. All three of these may even be found as surnames, today, and the kanji used for each comes from a particular dynasty, with various claims of connection. The strange thing is that the name associated—the way the name is pronounced—has no apparent connection to the dynasty or kanji in question, but it is thought that it may have something to do with a weaving technique or type of fabric or similar that may have been brought over and associated with each one, much like we associate porcelain with “China”. These may have originally been groups—probably with immigrant roots—who were dedicated to making the products in question. The names are:

Hata (秦) - This name references the Qin dynasty of the 3rd century BCE. Some sources would associate people of this name with the early attempts at finding the Island of the Immortals. Others claim that they traveled over to Jinhan during the Qin and later emigrated to the archipelago from there, possibly with the people of Yutsuki. Hata may reference weaving and looms.

Aya (漢) - This is less common, today, it seems. The name references the Han dynasty, and some stories connect them with Achi no Omi and his son, whom they claim descended from the Han ruling family before it fell. Aya likely refers to figured cloth.

Kure (呉) - This references the Wu kingdom, one of the Three Kingdoms that arose after the fall of the Han. I am less confident on what the word “kure” could have been referring to, but it seems obvious that much of what is called “Kure” in the chronicles would have to have been some other place.

Hachiman continues to be popular. Here, throngs of people visit his shrine in the seaside town of Kamakura, once the home to the Kamakura Bakufu. Today it is a pleasant daytrip from Tokyo.

Hachiman

The god Hachiman will be quite important in later centuries. For our purposes it is mainly the fact that he is associated closely with Homuda Wake that is of interest, though that is likely due to stories that came out around the 9th century.

If you are looking to read up on the early stories about Hachiman, his divinations, etc., Dr. Ross Bender did a lot of work in this area. You may want to check out his work on Hachiman and how it plays into the Dōkyō Incident.

Homuda Wake’s Kofun

Aerial photo of Kondayama kofun. Copyright © National Land Image Information (Color Aerial Photographs), Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism.

As with other early kofun, we are not positive that this one belongs to Homuda Wake, but it certainly is grand. It is the second largest kofun in size, but it is estimated that it has more actual material than any other kofun in Japan. There are several kofun around it, as well, crowding it, and earthquakes and erosion have done their fair share as well. By all accounts it does seem to be around the 5th century, and had an impressive number of Haniwa—though human figures would still be a little later on.

The informal name of the kofun seems to be “Konda Yama”, using the first two characters of Homuda Wake’s name: 誉田山.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is episode 48: The Life and After-Life of Homuda Wake

This episode is probably the last episode for Homuda Wake—we’ve covered some of the points about his reign, from the events written down on the Gwangaetto Stele in the 5th century, to the hostages from Baekje and Silla living at his court, all of which seem to indicate that the Wa were a power of some sort in the region—if not quite as powerful as their own Chronicles make them out to be. We are also told that this is when writing, in the form of Sinographic characters, first came to the islands, along with horses and classic continental literature. We’ve also talked about a few of the other characters from this period, including Takechi no Sukune and Katsuraki no Sotsuhiko, who dealt with things on the continent as well as those back at home. This episode we’ll continue with a few other things between the archipelago and the continent, and discuss briefly what this means. We’ll also discuss matters on the archipelago, such as the division of Kibi, Homuda Wake’s choice of Crown Prince, and more. And then, of course, we’ll talk about what happened after Homuda Wake’s reign—and we’ll touch briefly on how he is connected to one of the most famous kami in the archipelago: Hachiman, the God of War. We’ll talk about all that and finish up with a brief description of the kofun said to be his—one of the largest kofun in all of Japan.

Now, as a reminder, based on all of the stories and some of the events that can be corroborated with the peninsular records, we can make the assumption that this was all went down sometime in the late 4th and early 5th century, which is also a period of change in the archaeological record. Swords and suits of armor start to replace the bronze mirrors that had previously been common in large tombs, which would also seem to indicate that soldiers and martial pursuits were well valued, which certainly seems in step with the various conflicts both on the peninsula and within the archipelago.

And thus through trade and conflict, continental culture was flowing across the straits to the archipelago, where it was mingling with the people and traditions already present. Given the close ties between the islands and the peninsula throughout the previous centuries, it may be difficult to say just when any particular thing came over, but during this reign, as we’ve seen, travel and immigration in both directions was particularly noted.

Most of the immigration appears to be through Yamato’s close ally on the peninsula, the Kingdom of Baekje. Of course, some of those who came to Yamato were only temporary residents. These are the envoys and high status individuals like Prince Jeonji, King Asin’s own Crown Prince. Others seem to have come over on a more permanent or at least semi-permanent basis—primarily scholars and artisans. For instance, we already talked about how Ajikki was sent over with the Baekje king’s gift of horses to teach the Wa how to care for them and eventually raise horses of their own. And then there was Wang’in, who was brought over specifically to help teach the continental classics and how to read and write.

The Kojiki notes a smith, named Takuso, who also came over during this reign, and then there was the man known as Nipo, aka Susukori. He was a brewer, which put him in good stead with the court, who appreciated a good drink. Now we know that Yamato had alcohol, so this wasn’t exactly new technology, and we aren’t even told if he introduced anything particularly new to the archipelago. But he was, apparently, quite talented. He brewed a stiff drink for the Sovereign and his court, and it seems that everyone drank their fill, singing songs and just having a grand old time—in other words, not that much different from certain types of Japanese celebrations, today. Homuda Wake even made up songs of praise for Susukori, he was so pleased. Later that evening, the sovereign, Homuda Wake, staggered down the road, where he came upon a large rock. We are told that he struck the rock with his walking stick and sent it flying away.

From this seemingly innocuous incident we are told there was a kotowaza, or proverb, that you might even hear today:

Katashiwa mo Eibito wo Saku.

In English we might say: “Even a solid stone avoids a drunkard.”

Of course, it isn’t as if this proverb led to any kind of temperance movement. People continued to enjoy their adult beverages, nonetheless.

The other major craft that is mentioned as coming over during this reign was that of fabric arts. We previously mentioned the seamstress Maketsu coming over—a seamstress, likely bringing over continental fashions and how to make them. And then, elsewhere, they mention weavers—those who make the actual fabric from which the clothes are put together—coming over as well. The Kojiki mentions a weaver named Saiso, who is said to be from Kure, while the Nihon Shoki gives us more details.

In fact, it is in the Nihon Shoki where we hear the story of Achi no Omi and Tsuga no Omi, a father and son team. Achi no Omi himself is said to have immigrated from the continent around 409, bringing with him his son, Tsuga. They came to Yamato with a retinue of people from what the Chronicles call the 17 districts. While there doesn’t seem to be anything that firmly identifies just *which* 17 districts we are talking about, Achi no Omi is said to be the ancestor of the Yamato no Aya, where the name “Aya” utilizes the character for the Han dynasty. Later genealogies would claim that he was a direct descendant of the Han royal family, which might make sense if we were using the uncorrected dating of the chronicles, but seems less plausible for the 5th century. Nonetheless, there is a clear connection between him and the continental mainland, suggesting he may, indeed, have been an ethnic Han immigrant. The Yamato court would later ask Achi no Omi and his son to travel back to the land they had come from and to ask for weavers to be sent to Yamato.

Indeed, they headed out on their mission, but when they reached the peninsula, they couldn’t find a way to their apparent homeland. We are told they were headed to the court of Kure, more commonly known as Wu, one of the three Kingdoms that arose after the fall of the Han in the 3rd century. Which might have been accurate if we took the Nihon Shoki’s dates at face value, but even the Wu had been displaced by the time of our current sovereign, given our corrected dates, so if this happened then it was likely that they were traveling to either Eastern Jin, whose court was, at that point, operating out of the area of modern Nanjing, or else to one of the other, northern states that had arisen—perhaps one of the Yan or Wei kingdoms. This is known, after all, as the era of the Sixteen Kingdoms—though even that number may be off depending on how you count. Suffice it to say there are a lot of possibilities here for where they ended up.

Regardless, to get from the peninsula to the mainland, it seems that these envoys would need more than just the assistance of Baekje, and the Nihon Shoki claims that it was only through the help of Goguryeo, who provided them guides, that they were able to make the journey to “Kure”, whichever polity that was—which is somewhat interesting given that Baekje had established relations with the Eastern Jin by at least 372. It is possible that, given the turmoil on the peninsula several decades later, during the reign of Gwangaetto the Great, any unilateral path to the Eastern Jin court had been blocked, making Goguryeo the ultimate interlocutors for relations with the continent. Or perhaps, as mentioned, they were going somewhere else altogether. Either way, they were successful in their mission, and Achi and Tsuga returned with four weavers who brought with them the traditions of the mainland. Of course, we don’t have any clear evidence for this in any of the court records from the mainland, though, again, that may be understandable if they were dealing with one of the outer states and not a formal envoy to the imperial capital.

All of these stories demonstrate the kind of contact that the archipelago had with the mainland, and the individuals who were coming over, often starting new families who would, one assumes, become responsible of the production of continental goods in the archipelago. Information may even be hidden in the names, here. The names “Aya” and “Kure” for instance, though spelled with the sinographic characters for the Han and Wu dynasties, use a native Japanese gloss in their reading that doesn’t clearly identify with anything on the continent, but which may instead refer to the type of woven fabrics that were associated with each dynasty.

It is also interesting to me how the court was relying on a lot of continental assistance in the form of allies or immigrants to undertake these missions for them. Achi and Tsuga are said to have come over to the archipelago less than a decade before they were back up and heading back to the mainland. Horses and writing were sent to Yamato by the King of Baekje. Even the muscle that was being used on the peninsula was apparently a Baekje general.

But of course, it isn’t just what Baekje could do for Yamato—it was also about what Yamato could do for Baekje. Enter the story of Prince Jeonji.

Just a quick recap from previous episodes, Prince Jeonji was a hostage at the Yamato court, sent in 397 by his father, King Asin of Baekje, who came to the throne after the death—some sources suggest overthrow and murder—of Asin’s own uncle, King Jinsa. Prince Jeonji may have been sent to keep him safe, given that Goguryeo had previously defeated Baekje and taken several members of its court back with them, or he may have been sent to appease an angry Yamato. Either way, young Prince Jeonji grew up in Yamato until the unwelcome tidings of his father’s death reached the court 12 years later, in 405 CE, a date that seems to correspond between the Nihon Shoki and the Baekje annals of the Samguk Sagi with a clean break of 120 years, or two sexagesimal cycles of 60 years each.

Immediately, Homuda Wake suggested that Prince Jeonji return and take the throne, which I’m sure was entirely altruistic and had absolutely nothing at all to do with making sure that Yamato had a known quantity and a friendly ruler in place in Baekje. Homuda Wake even gave him command of 100 Wa soldiers to help.

Of course, this may have been more than just some courtesy. The Tonggam and the Samguk Sagi appear to agree that when King Asin died, his brother, Prince Hunhae, took over as regent until Prince Jeonji could return, and he was likely the one who sent for Jeonji in the first place. However, before Prince Jeonji could arrive King Asin’s youngest brother, Cheomnye, took the throne. The Samguk Sagi seems to make this out as an usurpation, but I would note that from what we’ve seen of the period and penn-insular succession rules in general, neither primogeniture nor patrilineal descent appears to have been necessary to claim legitimacy. In fact, in many cases it seems to have only been a requirement that one be the eldest—probably male—member of the family, and even *that* hasn’t been a hard and fast rule. Forms of agnatic succession—where the throne passes to a brother, rather than the sovereign’s own children—are definitely in evidence. This is all well and good, of course, until you get a couple generations in and suddenly have a plethora of potential royal candidates.

Anyway, it may have been this usurpation by Cheonmye that caused Homuda Wake to provide some Wa soldiers to help out. And yet, they were hardly used. Prince Jeonji made his way to the peninsula, but upon hearing that his uncle had usurped the throne, he withdrew with the troops to an island. There he waited until the people themselves, fed up with Cheonmye’s rule, overthrew him and placed Prince Jeonji on the throne as the true successor.

Now did the people really just overthrow Cheonmye, or did the Wa forces see a bit of action? We aren’t entirely sure, though it seems that the Baekje people have a suspicious habit of nobly rising up against a king as soon as it is convenient to prevent any whiff of the Wa having a hand in regime change. For my part, I see the heavy hand of Yamato in continental politics once again.

Of course, none of this should be too surprising, given the close association between the Wa and the peninsula. And here is where we get into territory that will likely cause some people a bit of a headache. Because there is plenty of reason to believe that a lot more came over from the continent than just new technologies. With artisans coming over and bringing others, as did Achi no Omi, they likely did what immigrants around the world have done and brought their own ideas, beliefs, and spiritual practices. We’ve already seen how material evidence of Yayoi spiritual life echoes, in some ways, the spiritual life that we see on the peninsula, and so it would seem no great stretch if the residents of the archipelago continued to incorporate some of the beliefs of the people immigrating into Japan. And so it is with little surprise that we see similarities in the ancient myths and legends of the archipelago with those of the continent. Even some of the kami that would come to be central to later beliefs, have connections with the continent. Susanowo is actually said, in some stories, to have first come down from heaven to the peninsula, where he then made his way over. And some of the aspects of the story of even Amaterasu Ohokami herself, and her weaving hall, seems to have a connection with the various weaver deity cults that we see elsewhere on the mainland. This is not to suggest that these are exactly foreign—the stories as we know them were still developing. For example, the kofun burials of this time were largely pit burials, dug into the top of the main mound of the kofun. It wouldn’t be until some time later that they would being a practice of building a corridor into the mound, which itself would seem to inspire some of the imagery around the whole world of the dead—the dark world of Yomi. And by that time, local and foreign legends and stories were merged, and foreign aspects were localized to the archipelago.

And there is nothing to suggest that the transfer was simply one way. It is hard to know what went from the peninsula to the archipelago and what went from the archipelago to the peninsula. Importantly, though, is that many of these things were transnational, meaning they crossed the various borders, often blending foreign and native concepts together. This is why I spend so much time talking about the mainland as well as the islands, because none of it developed in an isolated bubble. This often causes problems when people would like to have a clean narrative, especially for nationalists who want to see Japan and the Japanese Imperial Household as more isolated, unique, and unadulterated than it ever actually was. In contrast, we have plenty of examples of high ranking court nobles, whose offspring would marry into the royal line, with claims of continental descent. There is even an example of a Baekje princess who was sent to Yamato to become one of the sovereign’s wives.

Looking in the other direction, material culture, such as pottery and even burial practices from the archipelago show up in the peninsula from at least the Yayoi period onward. In the late 5th century we even see round keyhole shaped tomb mounds, oddly similar to those in the archipelago, showing up in the Yongsan River Basin in the southwestern peninsular region. This was a highly dynamic time for the region, during which many of the things that we may take for granted as being fundamental to Japanese history and identity were still being forged in the fires of international trade and immigration.

Back to the story of King Jeonji, there is one more event that I want to touch on here before we take a look at the rest of what was happening in the archipelago, and that is the death of King Jeonji. It seems that he was not fated to outlive Homuda Wake, and the Nihon Shoki claims that he died in 414, only nine years after his father and his return to Baekje. Upon his death his son, Kuisin, was named king, but he was still a child. And so a regent came to power: Mong Manchi. Now Mong Manchi was the son of Mong Nageunja, whom you may remember as the Baekje general who had helped in the late 4th century Baekje-Wa Alliance and who later had gone to Silla to stop Katsuraki no Sotsuhiko—though sometimes it is questionable whether he served Baekje, Yamato, or was his own independent warlord of some sort who allied with both.

Anyway, the excerpt of the Baekje Annals in the Nihon Shoki claims that Mong Manchi had taken over Baekje forcibly. According to the Nihon Shoki, with apologies to Aston, the Baekje record states: "Mong-man-chi was the son of Mong-na Keuncha, born to him of a Silla woman when he invaded that country. The great services of his father gave him absolute authority in Nimna. He came into our country [that is, Baekje] and went back and forward to the honourable country, accepting the control of the Celestial Court. He seized the administration of our country, and his power was supreme in that day. The court, hearing of his violence, recalled him." The Japanese Chroniclers of course assume that the “honorable country”, or “Kui-guo”, is Japan, as is the “Celestial Court”. Their own entry embellishes this story further, claiming that Mong Manchi was a subject of Yamato and that his actual crime wasn’t forcibly placing himself on the throne but rather having improper relations with the widowed Queen Mother.

Now this isn’t clear evidence of any actual Yamato interference and influence, at least not to my mind. After all, we aren’t sure that the “honorable country” actually referred to Japan, and the idea that Homuda Wake was presiding over something that Baekje would call the Celestial Court also appears to be equally suspect to my eyes. However the idea that that the throne of Baekje was briefly usurped by someone, possibly the King of Nimna itself may not be too farfetched.

And perhaps that is where we would leave it if it weren’t for one *tiny* detail. You see the Samguk Sagi and the Dongguk Tonggam appear to refute this whole story. They claim that King Jeonji didn’t die in 414, as the Japanese chronicle would appear to suggest, but rather that he died in 420, and his son, Kuisin, then took the throne, without any evidence of the kind of trouble suggested by the Baekje record in the Nihon Shoki. So what, exactly, is going on here? Did the Chroniclers just insert that entire episode in there because they thought it sounded good?

And with that, I think we’ll turn aside from the continent for a bit and focus on what else was happening on the archipelago. Much of the events recorded in the Chronicles are fairly standard compared with what we’ve heard about from earlier reigns. For example, even while Yamato was flexing its muscle on the continent, there were still independent entities on the archipelago. Mention is made early in Homuda Wake’s reign of the eastern Emishi attending with tribute, and they were put to work building the Mumazaka road, similar to the way that continental envoys were put to work building ponds, bringing into question, in my mind, just what sort of “envoys” these all really were. Then there is discussion of Homuda Wake meeting with the Kuzu, who are, in the Hitachi Fudoki, equated with the Tsuchigumo. In this case, though, they appear to be the kuzu of the mountains areas of the Kii peninsula, which suggests to me that while Yamato held sway over the plains and river deltas, where rice farming could be particularly successful, there may have still been plenty of independent groups living in the mountains, possibly with their own culture and values, which focused more on the mountain lifestyle than that of the plain-bound farming culture that largely sustained kofun-era Yamato. Of course, these are peripheral cultures, and therefore largely invisible in the text except when they directly interact with the people and court of Yamato.

In this instance we are given some insight into their ways—particularly into their rituals. For Kuzu offered songs and sake to the sovereign. In particular we are told that after they sang they “struck their mouths like drums” and laughed. The Kuzu are described as a plain and honest people who gather wild berries and boil frogs as a delicacy. They lived amongst the steep cliffs and ravines of the Yoshino river area, and produced such things as chestnuts, mushrooms, and trout. All of this speaks to me of people with very different lifeways from those common in the large settlements of Yamato.

But it wasn’t just the people living in the Japanese hollers and tucked away in the mountain crevasses who were outside of the larger Yamato polity, but there were plenty of other rice-growing areas as well. Of course, in either case, the Chroniclers extend the cloak of national unity over everything, but in this case I think we get a very interesting story, and it is tied in to Homuda Wake’s last queen.

I say his last queen because, based on what we’ve seen of royal succession to date, there appear to have been several. Takaki no Iribime, for example, is said to have been a descendant of Ikume Iribiko. She gave birth to one of the princes and eventual claimants to the throne. Then there was Naka tsu Hime—the Middle Princess, whom most genealogies name as the primary wife and queen, though little is actually said about her. She was a sister to Takaki no Iribime, we know that much, and their father was, oddly enough, Homuda no Mawaka no Miko, a royal prince with a name eerily similar to that of the sovereign, Homuda Wake. Naka tsu Hime would give birth to another eligible Prince.

But it is the last lady, who gave birth to the youngest of Homuda Wake’s eligible sons, who is the subject of our current story. She is Miyanushi Yagawa no Ye Hime, or the Elder Princess of Yagawa.

Now of the three possible claimants to the throne, Takaki no Iribime’s son, Ohoyamamori no Mikoto—who may be the same as Nukata no Oho Naka tsu Hiko—was the eldest son. Naka tsu Hime then gave birth to Ohosazaki no Mikoto. He was also eligible to become Crown Prince, and is the middle of three children who seem to have been in the running. The third eligible prince was known as Uji no Waka Iratsuko (or Uji no Waki Iratsuko), and he was the son of Miyanushi Yagawa Ye Hime, who was the daughter of Wani no Oho-omi, the great minister of the powerful Wani clan.

Ye Hime herself is mentioned several times throughout the reign, while Naka tsu Hime and her sisters are really only mentioned in the various lists of names and genealogies. Regarding Ye Hime, on the other hand, we get the full Hallmark treatment, from her courtship in Chika tsu Afumi to her later travels to Kibi.

Now the courtship of Ye Hime is given primarily in the Kojiki, where we are told of how they met and got married with the typical feasting that seems common in these kinds of stories. Ye Hime’s father has her serve Homuda Wake a large wine cup, which seems to have been about as close to a betrothal as you could get.

It is interesting that the Kojiki places all of this in Chika-tsu-Oumi, and in the song, that he sang at the feast, Homuda Wake seems to make the claim that he is from Tsunoga—aka Tsuruga Bay. That was where he had exchanged names with the Kami, and the area where Ame no Hiboko had been worshipped, which again begs the question about potential links between Homuda Wake and the peninsula.

The Nihon Shoki, however, gives Ye Hime a slightly different place of origin. For in that case we are told that one day, while they were both looking out over the land from a high tower, Ye Hime had a longing to go home and see her parents. And so Homuda Wake, who loved her so much that he would do nearly anything, summoned up 80 fishermen and had them take Ye Hime to Kibi. He even composes a song as she leaves where he calls her, quite blatantly, his spouse of Kibi.

And this seems a rather intriguing disagreement between the sources. The Kojiki has them meeting in what was presumably her home of Chika tsu Oumi—which is to say around Lake Biwa. Meanwhile, the Nihon Shoki claims that she is from Kibi. Of course, it could be that some other Ye Hime is meant in one of these accounts.

Either way, the Nihon Shoki claims that Homuda Wake then followed Ye-Hime to Kibi, dwelling in the palace of Ashimori, in Hata. This is traditionally identified as being along the Ashimori river northwest of modern Okayama city. This is an area with large, keyhole shaped tomb mounds that rival those in Yamato, and it may have actually been the home to an independent kingdom, particularly in the early 5th century.

This is why it is interesting what else we are told: That, while dwelling at Ashimori, Homuda Wake took a particular liking to a gentleman named Mitomo Wake, who, along with his entire family, waited on the sovereign, hand and foot. Eventually, Homuda Wake decided to divvy up the land of Kibi. Five of the various lands went to the five sons of Mitomo Wake, while the district of Hatoribe is said to have been given to his wife, Ye Hime, as her own. Mitomo Wake himself was designated as the Kuni no Miyatsuko, and his sons as Agatanushi, and the divisions—which may reflect later political boundaries—would largely remain in use, either formally or informally, until the present day.

Once again, we need to look beyond what the Chronicle is telling us. For instance, we know that there are huge, round keyhole shaped kofun in that region. The largest is known as Tsukuriyama Kofun, and it was built sometime in the late 5th century. By the way, “Tsukuriyama” is actually the name of several kofun, largely because its name merely means “man-made mountain”. In this case, though, we are talking about the fourth largest kofun in all of Japan, larger than most of the so-called imperial tombs. Many believe that it belonged to a king of ancient Kibi, and based on the size of the kofun, one who likely rivaled Yamato in terms of the power and labor that they were able to mobilize. And not only that, but the Kibi region has some of the densest concentrations of kofun outside of the Kinai region of central Honshu, built between the 4th and 7th centuries. There are over 140 of the large keyhole tombs, with at least twenty of them in the region of Tsukuriyama and the modern city of Okayama.

And yet I can’t help but note that they were following in the tradition set by Yamato in building a giant, round-keyhole tomb.

From the earliest stories, Yamato is said to have conquered and subjugated Kibi. But then again, they were also said to have conquered and subjugated the Korean peninsula, and in that case we have both textual and archaeological evidence to the contrary. Here we only have archaeological evidence, but I wonder: would Yamato have really allowed a subject to build such a large and grandiose resting place if they could prevent it? I figure at the very least it shows that the local elites had a fair amount of autonomy. Still, there are so many things that we are missing, and I wish we had records from outside of the main narrative, but alas, we will have to console ourselves with what the archaeology tells us.

Perhaps this story about Homuda Wake was actually about another king altogether—a king of ancient Kibi. Or perhaps there is some evidence here of an ancient marriage link to Kibi through his wife, Ye Hime, and perhaps even with her son, Uji no Waki Iratsuko.

Speaking of whom…

Now we know that Homuda Wake himself was quite enamored of his youngest son, and he had decided to make him the Crown Prince, which would seem fitting if he was actually the product of two powerful royal families. That said, he had at least two other sons who were apparently eligible for the throne, and if they didn’t support Uji no Waki Iratsuko’s claim it could be problematic after Homuda Wake’s death. And so, in one of those epic bouts of parenting that the royal lineage up to this point is so known for, he questioned his two elder sons, Oho Yamamori and Oho Sazaki, to ask, in a roundabout way, their thoughts. Of course, you can’t be direct with this kind of question, right? You know, just come right out and say, “Hey boys, I’m thinking of making your youngest brother the next ruler. You cool with that?” Nope, instead he sets up this whole elaborate thing. First he pulls them over to him and he comments about how they both have children of their own already—so they were already fully grown adults, themselves, by this time. He then asks which of their own children is more deserving of their love, the youngest or the eldest. Basically playing a game of “who does dad love the best” with the two that you’ve already decided are out of the running. Really?

Now, neither of the two other sons seem to have had any idea what he was getting at, but Oho Yamamori thought that this might be the moment to put in a bid for the throne himself. After all, he was the oldest, and he was the most experienced, right? Anyway, Oho Yamamori expounded upon the virtues of the older brother and how they were the most loved.

As Oho Yamamori went on about this, I imagine Homuda Wake’s visage took on a dark cast. You know that feeling when the audience has soured on what someone is saying, but they just keep going, anyway? Yeah, awkward…

So while Oho Yamamori was busy bombing on pitching their pater, Oho Sazaki saw what was happening and realized this wasn’t what their father wanted to hear. So when it got to his turn, he took a different tack, and he basically told his father what he thought he wanted to hear.

First off, he talked about how older children have already grown up and discovered their way in life. They were adults and had experience and could fend for themselves. The younger children, however, were still children. They didn’t have as much experience and therefore they needed the most love and support.

Clearly this was the answer that Homuda Wake was looking for. In the end, neither Oho Yamamori nor Oho Sazaki, despite their seniority, would be named the Crown Prince—that honor would go to their youngest brother, Uji no Waki Iratsuko. However, perhaps in response to the brown-nosing, he did appoint Oho Sazaki as assistant to the Crown Prince, and asked him to help administer affairs of state. Meanwhile he gave Oho Yamamori, well, he made him Oho Yamamori, which is to say the warden of the mountains and forested areas. This is probably where his name, or more properly title, actually comes from. His actual name may have been Nukata no Oho Naka tsu Hiko, but this is largely a guess on our part, based on the lists of Homuda Wake’s many offspring.

Of course, I’m sure that there were absolutely no hard feelings, and when Homuda Wake passes away, everything will be fine, right? Well, for that you’ll need to wait for the next episode.

First though, there is one more thing I’d like to touch on, though it isn’t exactly mentioned in the chronicles, and that is the story of Homuda Wake after his death. No, I don’t mean to suggest that he rose from the grave like some undead revenant, though that would have been a cool. Rather, I mean how the idea of Homuda Wake continued and evolved after his death.

So, yes, Homuda Wake did eventually pass away, and we are told he is buried in one of the large, round keyhole style mounds in the Mozu-Furuichi tomb mound group. But his spirit lived on in an interesting and, perhaps, appropriate way.

You see, centuries after his death Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, would be worshipped as one of the most famous deities of the archipelago, for he came be associated with the famous god-slash-Boddhisatva, Hachiman.

Now most people are familiar with Hachiman due to his later connection to the Minamoto family. His shrine in Kamakura, once the headquarters of the early shogunate, founded by Minamoto Yoritomo, is still extremely impressive, and an easy daytrip from Tokyo. But Hachiman was important before the Minamoto ever existed. And to examine the origins of Hachiman we are going to have to travel away from Kamakura and all the way to the western island of Kyushu.

It was here, on the island of Kyushu, that the cult of Hachiman was born, likely sometime in the 5th or 6th century, and the processes that come together in the founding of the Hachiman cult are highly demonstrative of the changes that are happening in the archipelago in general during the time of Homuda Wake, and so it is not entirely without merit that the two are linked, in my opinion.

It is difficult, of course, to know when an idea or story first comes into being, and much of what we have is based on the later information in works like the Shoku Nihongi, the successor to our current chronicles, and the founding tales of Usa shrine, that were passed down through the ages and eventually written down. Scholars suggest that originally this new tradition centered around a deity of a place called Yahata or Yabata, the native Japanese, or kun’yomi, reading of the characters in the name “Hachiman”. Yabata probably meant something like “eight fields”—a quite plausible locative, which could be just about anywhere in the archipelago. Eventually, though, worship of this deity took hold in Usa, one of the ancient settlement sites of northern Kyushu.

From the records we know that there were three families associated with Hachiman from an early time. One of these was, unsurprisingly, the Usa clan, who were probably the chieftains of the place with the same name. Usa comes up from time to time in the Chronicles, such as during Iware Biko’s march from Kyushu to Yamato, and later they were known for their Buddhist priests, whom they would occasionally send to the court. They certainly appear to have been an important place, even if the connection with Hachiman isn’t mentioned until much later.

Also involved in the early Hachiman cult were the Karajima. They appear to have been based out of the country of Toyo, but their name suggests that they descended from people who came over from the peninsula and settled there. The scholar Nakano Hatayoshi suggested that between the 3rd and 6th centuries they pushed south into the area of the Usa clan and conquered that region.

The last family were the Ohoga, whose name is just a different reading for “Ohomiwa”. Indeed, it seems they claim descent from the family charged with looking after the ancient holy site of Mt. Miwa, and they may have been sent out to the region as an extension of the Yamato court to help provide oversight of the Yamato-centered rituals. In fact, it may have been through such ritualist envoys that Yamato was able to exert some measure of control, along with sending out specialists in, of all things, burial mound construction—hence why we see the proliferation of the round keyhole style and related burial mounds in the kofun period.

And so we see here a merger of the local traditions, through the Usa clan, the Yamato traditions in the form of the Ohomiwa, and peninsular traditions of the Karajima. Three different traditions coming together.

It is this syncreticism that make Hachiman so interesting to many scholars of Japanese religion. To an outside observer, the shrines and rituals of Hachiman may closely resemble other forms of Japanese Shinto practice, but in many ways it is its own unique thing. At Usa shrine, Hachiman was venerated along with an image of Maitreiya Bodhisattva, and the worship of both was carried out together. Later, Hachiman would be designated as the protector of the Great Buddha at Toudaiji, in Nara, and the oracles of Hachiman would have significant impact on Japanese history.

The earliest records we have of Hachiman, in the 8th century, depict him as helping to secure a military victory, though this seems to have been a relatively minor part of his portfolio, at least early on. Later, as the chosen deity of the Minamoto clan, his God of War aspect would definitely be further developed. Initially, however, it was his role as a protector and his oracular divinations that caused such a splash. These divinations are at the heart of the famous Dokyo Incident in the 8th century, and came through the voices of the priests and mediums of Usa Shrine, rather than divine visions of the sovereign or reading the cracks on burnt deer scapulae or turtle shells. This was different from the type of divination generally seen with other kami, and it has been suggested that it was the result of a combination of practices from the peninsula and on the archipelago. It also likely didn’t hurt that there was no one single family that could lay claim to Hachiman and his cult. He was, in a way, a free agent, meaning that he could be shaped by later courts and sovereigns into what they needed him to be.

The connection of Hachiman with Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, actually comes in rather late. It is in the 9th century that we get a text which tells us that Hachiman revealed himself to be Oujin Tennou to the sovereign known as Kimmei Tennou in the mid-6th century, after Hachiman had already been adopted by the royal house as a protector.

In all likelihood, Hachiman had nothing to do with Homuda Wake until centuries after the fact. But even then it is intriguing to think about just what Homuda Wake meant to people. By all accounts he seems to have been from a different dynasty than the 8th century ruling family, though his line was important enough for them to work into their own narrative, and his story is often tied up with the reign of his mother—where Okinaga Tarashi Hime was a conquerer and warlord, the story of Homuda Wake focuses more on assimilation of new people and ideas. This balance of martial prowess—Wu or Bu—with literary pursuits—Wen or Bun—is a common dichotomy in Asian thought and philosophy, and so it is unsurprising that the narrative might reflect that.

And yet, as Hachiman, Homuda Wake is often depicted wearing arms and armor, and as much a conquering hero as an administrative governor. Of course, these different aspects may better reflect the needs of the people at any given time, rather than any core aspect of Homuda Wake’s character.

And with that, we have just one more thing to discuss before we move on and say farewell to Homuda Wake, or at least his human incarnation—as Hachiman he will definitely be putting in an appearance in later episodes, don’t you worry. Now this wouldn’t be the kofun period if we weren’t talking about the giant kingly tombs that these sovereigns are said to be buried in, and in Homuda Wake’s case it is a grand tomb, to be sure.

Measuring 425 meters in length, the Ega-no-mofushi no Oka Kofun, also known as the Konda Gobyou Yama or just Konda Yama Kofun, is the largest of the Furuichi kofun group, which lies in modern Ohosaka, south of the Yamato River, and just west of the mountain pass leading to the Nara basin. Not only is it the longest in its group, but it is the second longest in all of Japan, and the largest by volume of any of the kofun in the archipelago. As for the largest kofun, at least by length, that distinction falls to Daisen kofun, which lies just a little ways to the west in the Mozu kofun group, and which is said to be the burial site of Homuda Wake’s son, the sovereign known as Nintoku Tennou. Together they are part of the UNESCO World Heritage Mozu-Furuichi Kofun group, which attained official status in 2019. This is the height of kofun construction in the archipelago, at least for sheer monumental size.

In addition to its size—and the impressive array of haniwa figures that adorned it--Kondayama Kofun is, predictably, also the site of a shrine to Hachiman—Konda Hachimangu. By the way, I should probably note, since you can’t tell through the microphone, that the “Konda” here is just another reading of the name “Homuda”. The shrine itself claims that it was originally built in the front of Homuda Wake’s mausoleum in about the 6th century, and then later moved to the present location (south of the mound) in the 11th century. I have reason to question this, but that is the claim that the shrine appears to make.

And that’s all that I really have for you this episode. I appreciate everyone who has stuck with it—there has been so much this reign, it has taken us roughly six episodes to get through it all. Next episode, though, we get to move on and we’ll see just who becomes the next sovereign. Is it young Uji-Waki-Iratsuko, who was the designated Crown Prince and Successor? Or perhaps Oho Yamamori, who was passed over by their father. Or perhaps Oho Sazaki will step up. You’ll just have to wait and find out next episode.

So, until next time, thank you for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate through our KoFi site, kofi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the link over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode. Questions or comments? Feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page.

That’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Lee, D. (2014). Keyhole-shaped Tombs and Unspoken Frontiers: Exploring the Borderlands of Early Korean-Japanese Relations in the 5th-6th Centuries. UCLA. ProQuest ID: Lee_ucla_0031D_12746. Merritt ID: ark:/13030/m52j7s88. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7qm7h4t7

SCHEID, B. (2014). Shōmu Tennō and the Deity from Kyushu: Hachiman's Initial Rise to Prominence. Japan Review, (27), 31-51. Retrieved August 10, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23849569

Kawagoe, Aileen (2009). “Did keyhole-shaped tombs originate in the Korean peninsula?”. Heritage of Japan. https://heritageofjapan.wordpress.com/following-the-trail-of-tumuli/types-of-tumuli-and-haniwa-cylinders/did-keyhole-shaped-tombs-originate-in-the-korean-peninsula/. Retrieved 8/24/2021.

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Shultz, E. (2004). An Introduction to the "Samguk Sagi". Korean Studies, 28, 1-13. Retrieved April 11, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23720180

Ishino, H., & 石野博信. (1992). Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 19 (2/3), 191-216. Retrieved August 16, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30234190

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Bender, R. (1979). The Hachiman Cult and the Dōkyō Incident. Monumenta Nipponica, 34(2), 125-153. doi:10.2307/2384320

Bender, R. (1978). Metamorphosis of a Deity. The Image of Hachiman in Yumi Yawata. Monumenta Nipponica, 33 (2), 165-178. doi:10.2307/2384124

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1

Hall, John W. (1966). Government and Local Power in Japan 500 to 1700: A Study Based on Bizen Province. Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0691030197