Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode there is definitely a need to help sort out some names. We’ll start right up front with a lineage chart so that you can see how some of the

So let’s go through some of the Who’s Who here:

Kashikiya Hime

The sovereign, Suiko Tennō. She was the daughter of Amekunioshi and Kitashi Hime. Kitashi Hime was the daughter of Soga no Iname. She then married her half-brother, Nunakura Futodamashiki (Bidatsu Tennō). She was likely just another consort, but when Nunakura’s designated queen, Okinaga no Hirohime, passed away, Kashikiya Hime was raised up in her place—or so we are told. After Nunakura’s death, his son and presumptive heir, Prince Hikobito, was killed in the chaos during the next several reigns. Kashikiya Hime’s brother, Tachibana, came to the throne as Yōmei Tennō, and later her half-brother, Anahobe no Hasebe, as Sujun Tennō. Tachibana died early into his reign, assuming he did actually reign, and Hasebe was killed by Soga no Umako, the “great minister” (ōmi) and uncle to both Hasebe and Kashikiya Hime. Kashikiya Hime was eventually put on the throne and became known to us as Suiko Tennō. Her son, Prince Takeda, passed away at some point—possibly before she came to the throne. And so she made her nephew, Prince Umayado, aka Shōtoku Taishi, the heir and Crown Prince.

In the end, she outlived both Umayado and Umako, passing away in 628 CE, having reigned for about 35 years or so.

Prince Takeda

Prince Takeda was the son of Kashikiya Hime and Nunakura Futodamashiki. His position as a possible heir is evidence through the fact that he was targeted by Nakatomi no Katsumi along with Prince Hikobito during the Soga-Mononobe conflict that was part of the larger struggle for the throne at the end of the 6th century. He must have passed away at some point—the last we see of him in the Nihon Shoki is in 587, during the assault on the Mononobe. We know that he predeceased his mother as she was buried in his tomb. This is traditionally believed to be Yamada Takatsuka kofun, but may refer to another nearby kofun. Both of these are rectangular kofun. In the case of Takatsuka, it may have originally been square and then had the shape changed at a later point, which might indicate Kashikiya Hime’s burial and modifications made to the tomb. This could also help explain why Kashikiya Hime’s burial took so long.

Soga no Ōmi no Umako

Umako was the son of Soga no Iname, the scion of the Soga household, and the “great minister”—the chief position of the court, especially after he led the Soga family and allies against the formerly powerful Mononobe. He is depicted helping Kashikiya Hime rule, but predeceased his niece by several years. His position as Ōmi and head of the Soga house passed to his son, Soga no Emishi.

Soga no Sakaibe no Omi no Marise

Marise is a somewhat enigmatic figure. The Chronicles do not clearly give his relationship to Soga no Emishi and Soga no Umako, but they do indicate that he is a member of their family. Current understanding is that he was brother to Soga no Umako, and uncle to Soga no Emishi. The name “Sakaibe” (or Sakahibe) first shows up during this reign, and Marise is mentioned several times throughout the reign, including as a general fighting on the Korean peninsula and providing a eulogy at Kitashi Hime’s burial.

Soga no Ōmi no Emishi

Son of Soga no Umako. He took over the role of Ōmi after his father passed away. He was the head of the Soga family, but he doesn’t seem to be very active prior to the events of 628, at which point he appears to have been trying to gain an even stronger position. Although he likely inherited the position from his father, in 628, Soga no Emishi, he didn’t have the string of political victories behind him that his father had.

Prince Yamashiro no Ōe

Yamashiro no Ōe was the son of Prince Umayado and Tojiko no Iratsume. Tojiko herself was the daughter of Soga no Umako, and thus sister to Soga no Emishi, making Emishi the uncle to Prince Yamashiro. As the son of Umayado, living at the palace at Ikaruga, it would be logical to think that he would be the heir, since had Umayado come to the throne then Prince Yamashiro would have naturally been next in line, especially given his direct maternal connection to the powerful Soga family.

Prince Hase

Aka Prince “Hatsuse” was another son of Prince Umayado, and half-brother to Prince Yamashiro. His mother was Kashiwade no Hokikimi no Iratsume. We are given very little about him, other than he seems to have lived in Ikaruga with his half-brother, and was one of his brother’s supporters for the throne.

Prince Tamura

Prince Tamura is the son of Prince Hikobito, the apparent heir presumptive under Nunakura Futodamashiki by his wife, Okinaga no Hirohime. That name “Okinaga” shows up in the royal lineage at least back to Okinaga no Tarashi Hime, aka Jingū Tennō. If we take the position that every sovereign is supposed to be descended from a “royal” lineage, then it may be that Hirohime’s children had a stronger claim to the throne than any of the Soga descended lines. In addition, Prince Tamura’s mother was Nukade Hime, a daughter of Tachibana, aka Yōmei Tennō, and a half-sister to Prince Umayado. That all gave Prince Tamura a fairly strong claim to the throne. Whereas previous challenges have come from individuals that we are told are bothers, here we have two competing lineages, both tracing all the way back to Amekunioshi Hiraki Hiro Niwa, aka Kinmei Tennō.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is episode 103: The Queen is Dead.

Quick content warning up front, while most of this is just politics, there is mention of some violence and even suicide towards the end of the episode. I have attempted to keep it mostly to the facts, but if that is something that concerns you, please be aware.

The year is 628, and the mood in the inner chambers of the palace is somber. The court is no stranger to illness; after all, when the Oho-omi, Soga no Umako, had grown ill, a thousand individuals had entered religion to pray for his recovery. He had recovered from that, indeed, only to pass away two years ago. His son, Soga no Emishi, had taken his place at court and at the head of the powerful Soga family.

This time, though, it is different. The sovereign, Kashikiya Hime’s illness affects the entire court. After more than 30 years of her rulership, it seems that the Great Queen of Yamato will not recover, this time. A handful of maids and selected members of the royal family are called into the inner chambers of the palace, tending to her in her final moments. The mood is tense, not just because of the impending death, but also because of the uncertainty for the future. After all, the Crown Prince, Umayado, had passed away approximately six year earlier, and nobody has been named as his replacement. Kashikiya Hime’s own son, Prince Takeda, had passed away some time earlier and is already buried.

Now the inner circle wonders if she will name he successor, or will she pass on without doing so, leaving the throne empty, and setting up yet another bloody power struggle like the ones at the end of Nunakura Futodamashiki’s, aka Bidatsu Tennou’s, reign. Many people still remember what had happened then—they had possibly even lived through it, recalling the Soga and the Mononobe raising up armies, the fighting across the land, and the accusations and repercussions that followed, and forced many on the losing side into hiding.

And they know there are several candidates waiting in the wings. For example, there is Prince Tamura, son of Prince Hikobito, who had been slain in the succession disputes that eventually ended up putting Kashikiya Hime on the throne. That made him a grandson of Nunakura Futodamashiki no Ohokimi and his first wife, Hirohime. His mother is the royal princess Nukade, daughter of Tachibana no Ohokimi and sister to Prince Umayado, aka Shotoku Taishi, giving him a full royal pedigree to draw from.

There is also prince Yamashiro, the eldest son of Prince Umayado and Tojiko no Iratsume, one of the daughters of the late Soga no Umako, the powerful Oho-omi who had raised up the Soga family. Umayado’s fame is well known as the saintly Shotoku Taishi, the previous Crown Prince. He is known to be close to the queen, Kashikiya Hime, and there is not a little bit of speculation as to whether or not she will name him to take up his father’s mantle. He has, after all, succeeded his father in his own household, living in his father’s palace at Ikaruga, near the family temple of Houryuuji.

Both candidates, Tamura and Yamashiro, are called to Kashikiya Hime’s bedside, and there she gives each of them instructions as to what to do upon her demise.

Not too long after that, Kashikiya Hime passes away.

The Queen is dead. Long live the… well, who, exactly?

--------------

So we have been covering Yamato during the reign of Kashikiya Hime, from 593 right up to 628, and what a reign it has been. The Soga family had married into the royal line and then, with the death of Nunakura Futodamashiki , placed princes of Soga descent on the throne. And if you want to go back and listen to all of that, then probably go back to about episode 90 or so. During this period, we’ve seen the building of Buddhist temples—at least 46, we are told—and we see Yamato explicitly adopting certain concepts of statecraft and kingship from the continent. I say explicitly because there are certain things, like the Uji and Be system of clans and the accompanying kabane ranking system that appear to have come over as well, but the Chroniclers never really acknowledge that, treating it as though they were always a thing. We see the rise of the Sui and transition over to the Tang dynasty on the continent, and Silla continue to expand and solidify their control on the peninsula.

We are now towards the end of the reign. As noted before, Prince Umayado, aka the Crown Prince, Shotoku Taishi, passed away in about 622, and after he died, no other Crown Prince appears to have been selected. Umayado was one of the three people seen as holding the reins of state at this time, with the other two being Kashikiya Hime, of course, and her uncle, Soga no Umako.

There are some who even suggest that Soga no Umako, as Oho-omi, was actually in control, and Kashikiya Hime was simply a puppet figure. That seems to be countered by something that happened about 623 or 624, two years after Umayado passed away, when Soga no Umako sent Adzumi no Muraji and Abe no Omi no Maro to Kashikiya Hime to request that he be given the district of Katsuraki, as that is where he was from and where he took his name. Beyond the fact that this gives us some insight into the origins of the Soga family—or at least the origins they claimed for themselves—it is interesting for us now because of Kashikiya Hime’s response. She first noted her close ties to her Soga uncle, and went on to say that, under normal circumstances she would do anything she could to fulfill his requests, but in this case, it was a little bit too much, even for her. If she said yes and gave him and the Soga family the entire district of Katsuraki, what would future generations say about her?

Now it is difficult to say if this actually happened, or if it was part of what appears to be a smear campaign against the Soga family, who, spoiler alert, would eventually be accused of trying to usurp the power of even the sovereigns themselves. That said, it seems like the kind of thing that is just plausible, though possibly using a bit more justification to back up the request. Still, the Chroniclers at least were providing agency to Kashikiya Hime.

Soga no Umako, who had been Oho-omi for some time, would pass away a few years later. That year, we are told that peach and plum trees blossomed, and that the third month of the year, probably late March or April, it was particularly cold, and a hoar frost fell across Yamato. Two months later, Soga no Umako died.

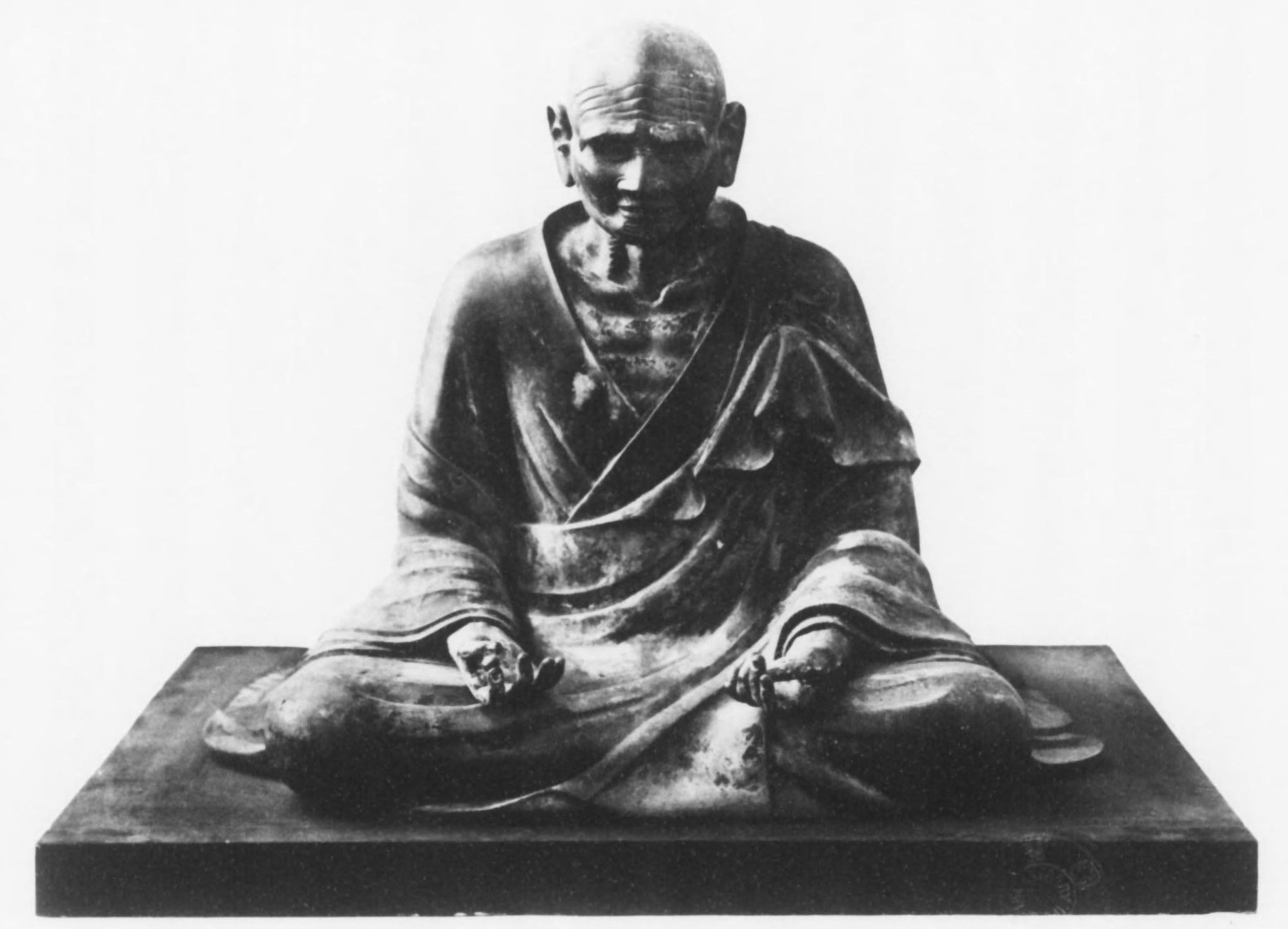

He was buried at Momohara, probably at the place known as Ishibutai Kofun. This was a large, square shaped kofun, but today it has all but worn away, so that you can see the giant stones that once made up the internal structure of the tumulus. Unfortunately, this means that any grave goods have long since been taken and any organic material has probably completely disappeared, but it is an amazing tomb to get an idea of what inside of a 7th century kofun looks like.

Soga no Umako lived in the family mansion on the banks of the Asuka river. We know roughly where it was, since Houkouji Temple used part of the Soga land for its own founding, and so would have been right next to Umako’s mansion. We also know that it had a water feature, a kind of pond, with an island, or “Shima”. Sometimes Soga no Umako would be known as Soga no Shima. I suspect that his son, Soga no Emishi, who took up Soga no Umako’s post as Oho-omi, also took up residence here, as the Sendai Kuji Hongi also references him as Soga no Shima at one point, though that could just be a mistake of some kind.

The next month after Soga no Umako’s death was also pretty bad—we are told that snow fell in the sixth month, and then there were continual rains from the 3rd to the 7th month. This led to famine, and both the old and young died of starvation or disease. People were eating whatever weeds and herbs they could find, and banditry and thievery increased as people grew more and more desperate.

It didn’t get any better the next year, which saw more omens and strange reports. Apparently a badger up in Michinoku, referring to the Tohoku region, turned into a man—possibly a reference to similar stories about tanuki and the belief in other shape-changing animals, but definitely a weird thing to occur. And then, there was a huge swarm of flies, we are told, that gathered together and flew east over the Shinano pass. Reports said they were as loud as thunder, and they dispersed when they reached the land of Kamitsukenu. Aston suggests this probably refers to Usui Toge, a pass between modern Yamanashi and Gunma prefectures, near Karuizawa.

I don’t have any explanation for either event to give you. I’m sure it meant something to the people of the time, but looking back, I suspect they were interpreted as stormclouds on the horizon. And that is because, in the 2nd month of 628, Kashikiya Hime took ill. On the second day of the following month the Chronicles record that there was a total eclipse of the sun, and four days later, Kashikiya Hime took a turn for the worse.

Fun fact in this morbid narrative: that total eclipse of the sun might just give us a verifiable date, here, because we can calculate astronomical phenomena like eclipses. In fact, given the impact of the events around this particular one, it has been specifically studied, and you can check out the work of Tanikawa Kiyotaka and Souma Mitsuru, titled “On the Totality of the Eclipse in AD 628 in the Nihongi”, published in 2004 in “Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan”, and I’ll provide a link in the blog post. TL:DR – There was an eclipse on April 10, 628, and based on the work of Tanikawa and Souma it was likely visible from the archipelago. There is some question as to whether or not it was a “total” eclipse when viewed from the Nara basin, and specifically from the palace at Asuka, and it is even possible that the Chroniclers were using continental records to verify the actual dates and conditions—not to mention the way that stories can grow in the telling of them. However, it is highly likely that they did witness an eclipse of some sort, and this gives us some solid dates for everything else.

That means that Kashikiya Hime likely took ill in late March of 628, and then her illness took a turn for the worse on the 14th of April, at least according to our modern calendar.

And yes, there is some discrepancy in those. We would say that April 14th is the 14th day of the fourth month, not the sixth day of the third. However, we are dealing with the conversion of ancient, lunar calendar dates into a modern, western, solar calendar dates. Even now, just a few days before this episode airs, we just went through the Lunar New Year in much of Asia, based on the descendant of that same lunar calendar. That New Year happened February 10, 2024, but for the Lunar calendar, that would be the first day of the first month. And that isn’t even going into all the various corrections that both calendars have gone through over the centuries—don’t get me started on Julian versus Gregorian dates, or how that affects various lunar festivals that are now tied to a solar calendar. However, I think that putting the date in a modern, solar calendar context can help people get a better appreciation of the seasons and what was going on. As Kashikiya Hima took ill, spring had sprung in the Nara basin, and the cherry blossoms were likely in full bloom. And yet, even as that was happening, the mood in the palace was dire.

It’s fitting, perhaps, because today, cherry blossoms, for all their beauty and the fact that they are blooming at a time that life is seemingly returning, are often considered a metaphor for the all too fleeting impermanence of this mortal existence. They blossom in beautiful and spectacular color, but all too quickly they are gone.

And so, too, did it seem that Kashikiya Hime’s time was coming to a close. She was 75 years old, and she had ruled the realm since 592, about 36 years, not including the time before that spent as a consort or the two short reigns in between. She had been the sovereign over some of the most influential periods of Yamato history, including the spread of Buddhism and the introduction of new, continental styles of learning and governance.

Now, she was on her deathbed. Surrounded by her maids and various royal princes and princesses, she called two of those princes, in particular, to her bedside. Specifically, she called Prince Tamura and she also called Yamashiro no Ohoye. As previously noted, they were the two most likely candidates for succession. Kashikiya Hime provided instructions to each of them in relative privacy, and those appear to have been her last words, as she passed away the next day.

As was customary, she was temporarily placed in the southern hall of the palace while arrangements were made for her funeral.

Preparations for here burial would take some time, and so it was on the 20th day of the ninth month—over 6 months later—that the rites to officially mourn the deceased sovereign were held. A shrine was erected at the southern court of the old palace, which served as her temporary burial place, and each minister pronounced a funeral eulogy. Four days later, she was buried, in accordance with her wishes, in the tomb of her son, Prince Takeda, who had passed away before her. She had requested this, instead of building her own tomb mound, to avoid placing a burden on the country given the famine that people had been going through, or so we are told. Traditionally, she is believed to have been buried at Yamada Takatsuka Kofun, aka Takamatsu Kofun, in Yamada, in the Taishi-cho area of the Southern Kawachi district in modern Osaka, though some have suggested nearby Ueyama Kofun. Both are rectangular kofun, rather than the keyhole shaped tombs of previous rulers, but that makes sense if she was buried in the kofun that had been built for her son, who never sat on the throne. It also may just speak to the changing norms of the time, where keyhole shaped tombs seemed to no longer be the done thing.

Regardless of where she was buried, her death left a power vacuum, as there was no clearly designated heir to the throne. There were at least two candidates, and we’ve seen where that has led in the past—warfare and bloodshed. No doubt there was a palpable feeling of anticipation and anxiety around Kashikiya Hime’s death. Would rival camps start feuding, once again, over who should sit on the throne? Would there be another deadly fight for power?

In addition to the existential threat, whoever the new sovereign was that came to power could have huge effects on the court. They could appoint new families to take the Oho-omi or Oho-muraji positions, and they would no doubt reward those who supported them in helping to come to the throne. Those on the losing side could find themselves on the political outs—or worse.

Soga no Emishi was the most powerful member of the court at that time. He was the current head of the powerful Soga family, the son of Soga no Umako, and the Oho-omi, the most powerful position in the court. He had his own thoughts on who should be sovereign, and if he could have, no doubt he would have simply appointed someone and made it a fait accompli. However, even his power had limits, and he knew that if he put someone on the throne unilaterally he would likely be opposed by the other ministers, if only because they didn’t want to cede him that much power. Therefore, he would need to get them to go along with it.

And so, one of the first things he did was to press his uncle, Sakahibe no Marise no Omi, asking him his thoughts about whom the new sovereign should be. Marise told Emishi that he believed Prince Yamashiro would be the best candidate. Remember, Prince Yamashiro was the son of the Crown Prince, the late Umayado, aka Shotoku Taishi. His father had been well respected and deeply involved in all aspects of the government, and Prince Yamashiro had largely taken his place, living as he was in his father’s old compound in Ikaruga, where Umayado had erected the temple of Houryuuji. On top of that, he was a royal prince of Soga descent—with multiple connections to Soga no Iname as well as his mother’s own descent from Soga no Umako. One might assume that he would have some loyalties to his extended family.

However, this answer didn’t sit so well with Soga no Emishi, who had his own preference for Prince Tamura. Prince Tamura was not so directly a Soga descendant, but rather more directly descended through what some have referred to as the “Okinaga” line of the royal family. At first glance it might seem odd that he would support someone from outside of his family, but consider this: if Prince Yamashiro were to take the throne, then he becomes the most powerful “Soga” descendant. Those with ties to the Soga could easily support him over Soga no Emishi, especially with the addition of royal blood. Often we see that when it comes to “family” loyalty, the divisions within a family can often be more brutal than external feuds. This is a theme that will echo through the centuries.

Prince Tamura, on the other hand, was a relative outsider. If Soga no Emishi helped him to the throne, then Prince Tamura’s own power and authority would be thanks to Emishi’s work, and at least somewhat dependent upon him and the rest of the powerful Soga family. Furthermore, he was married to Hotei no Iratsume, another daughter of Soga no Umako and thus Soga no Emishi’s sister. Soga no Emishi may have felt that his connection to his sister and brother-in-law was better than that to Prince Yamashiro.

I’d also note that if Sakahibe no Marise really was Emishi’s uncle, that meant that he was also a rival for the head of the Soga house, since, as we’ve seen, inheritance often went to siblings before it made its way down to the next generation. I mention that only to further demonstrate the complicated familial politics of the time, where traditions of inheritance were not strictly laid out.

Seeing as how there was not a consensus even within the Soga family, Emishi decided he would need to win people to his side if he wanted to do this pick this —and how better to do that than to throw a party? Emishi conspired with Abe no Maro no Omi, and they invited everyone over to the Soga mansion for a feast.

Soga no Emishi wined and dined the who’s who of the Yamato court. They ate and drank their fill and, by all accounts, had a great time, likely putting aside the tensions of everything going on outside. As the party began winding down, Emishi had Abe no Maro broach the subject of succession. And so, Abe no Maro addressed the crowd. He started with what was likely on everyone’s mind: the fact that the sovereign was dead, and there was no clear successor. If they, the ministers of the court, didn’t figure something out soon then they were likely to see civil disturbances. So whom should they agree to succeed her?

He then recounted what people had heard regarding her majesty’s final wishes; although the conversations had been held in the relative seclusion of her own private quarters, to which only a handful of people were typically invited, there were still attendants who had been there, and as such word had leaked out. According to that game of ancient telephone, Kashikiya Hime had called in Prince Tamura and told him that “The Realm is a great charge, and, of course, not to be lightly spoken of. Be watchful and observant, Prince Tamura, and not remiss.” Then, to Prince Yamashiro she said, “Avoid your own brawling speech and make sure to follow what everyone else has to say. Be self-restrained and not contentious.”

And so, Abe no Maro asked, who should we make the new sovereign?

At that point, he was met with an awkward silence. Things had been going great, but Abe no Maro had just committed a party foul and brought up politics. So much for the fun and games.

Finally, Ohotomo no Kujira no Muraji spoke up. “Why don’t we simply obey her majesty’s final commands?” he suggested, “There is no need to go out and seek a general consensus.”

Challenged by Abe no Maro to expound on this, Kujira continued to explain his thoughts. Since Kashikiya Hime had said to Prince Tamura that the realm is a great charge and he should “be not remiss”, wasn’t it clear that she had made up her mind to hand it over to him? Who were they to say otherwise?

At that point, four other ministers spoke up. They were Uneme no Omi no Mareshi, Takamuku no Omi no Uma, Nakatomi no Omi no Mike, and Naniwa no Kishi no Musashi. They all agreed with Ohotomo no Kujira and agreed that they should end discussion, essentially casting their votes for Prince Tamura.

However, not everyone agreed with this. On the other side of the aisle were Kose no Omi no Ohomaro, Saheki no Muraji no Adzumoudo, and Ki no Omi no Shihote, who all threw their support behind Prince Yamashiro.

That’s roughly five ministers vocally for Prince Tamura, not including Abe no Maro and Soga no Emishi, but there were at least three on the other side, as well as Sakahibe no Marise, Emishi’s uncle. There may have been others that are not mentioned.

That left one person who hadn’t spoken up: Soga no Kuramaro no Omi, aka Soga no Womasa, Soga no Emishi’s own brother. He was on the fence about the whole thing, and asked for time to think it over. Given all of this debate, it was clear to Soga no Emishi that there was no unanimous decision—at least nothing with unanimity, or at least approaching it. If so many of the nobles were on the other side, then a decision risked splitting court, and therefore bringing more chaos to the land. Furthermore, a split decision could risk a split in the Soga family itself. And so he retired and sent everyone home from the party.

Of course the court was hardly a place for secrets, and pretty soon Prince Yamashiro got word of the discussions that were taking place. And so he sent a private message to Emishi, by way of the royal Prince Mikuni and Sakurawi no Omi no Wajiko. He basically asked what’s up, and why Emishi would want to put Prince Tamura on the throne instead of him.

This was apparently a bit awkward. Prince Yamashiro was asking Emishi as his uncle—distant though that relationship may have been. Rather than going to Prince Yamashiro to reply in person, Emishi instead gathered a bunch of the ministers who had been at the feast and sent them—including members of both the Pro Tamura and Pro Yamashiro factions. At Emishi’s direction, they went to Yamashiro’s palace at Ikaruga and delivered Emishi’s message. Through them he asked how they should be so rash as to decide the succession all by themselves? All that was done was that her majesty’s dying commands had been conveyed to the ministers. Then the ministers had said, with one voice, that Prince Tamura was that, based on her majesty’s words, was the natural heir to the throne, and were there any objections? This was all the words of the various ministers, not any specific sentiments of Soga no Emishi, who claimed that though he had an opinion he refrained from communicating it until he could talk with Prince Yamashiro face to face.

And here we get an inkling of the way these communiques were happening. Because it wasn’t like the ministers just went up to Prince Yamashiro directly. They went to his mansion, but, much like in the palace, they offered their communications via intermediaries. In this case they told Prince Mikuni and Sakurawi no Omi, who were apparently attending on Prince Yamashiro, and then those two passed the words on to Prince Yamashiro. The implication seems to be that should Soga no Emishi have come himself, I suspect that they would have talked in private. As it was, the words were apparently public, which also means that both sides had to choose their words carefully. It also allowed Emishi to have some amount of deniability.

And so after Prince Yamashiro had heard what his intermediaries reported, he asked them to go back out to ask the ministers just what they knew of the dying wishes of Kashikiya Hime, and they reported what Soga no Emishi had told them, admitting that none of those present had actually been there. Rather, the words had been reported to them by the Princesses and Ladies in Waiting attending to her Majesty—but surely Prince Yamashiro, who had been there himself, knew all of this.

Prince Yamashiro then asked directly if they had heard the actual words, and all of the high ministers there admitted they had no knowledge of the specifics, just what they had heard, second-hand.

Prince Yamashiro then offered *his* version of events, which was slightly different than what Soga no Emishi had suggested. On the day that he was summoned, Prince Yamashiro claimed, he went to the palace and waited at the gate. He was finally summoned in by Nakatomi no Muraji no Mike, who came out from the forbidden—or private—quarters and Prince Yamashiro then proceeded to the Inner Gate. In the courtyard he was met by Kurikama no Uneme no Kurome and led to the Great Hall, where there tens of people in attendance, including Princess Kurimoto and some eight ladies-in-waiting, including Yakuchi no Uneme no Shibime. Prince Tamura was also there, of course—apparently he had already talked with her Majesty.

Kashikiya Hime herself was lying down in bed, and could not see Prince Yamashiro enter, so Princess Kurimoto went to inform her that he had arrived. With that, Kashikiya Hime raised herself up and, according to Yamashiro, gave him the following command:

“We, with our poor abilities, have long borne the burden of the crown. But now our time is drawing to a close, and it seems we cannot escape this disease. You have always been dear to our heart and our affection for you has no equal. The great foundation of the State is not a thing of our reign, alone, but has always demanded diligence. Though your heart is young, be watchful over your words.”

Prince Yamashiro then emphasized that everyone who was there, including Prince Tamura, heard and knew what she said, and expressed how he was full of both awe and grief. He leapt for joy, as he heard her words, which he understood to be her passing on the mantle to him. He did, though, have his concerns. He was young, and inexperienced—“devoid of wisdom” is the wording as Aston translates it. How could he accept a charge to handle issues with the Spirits of the land and of the various ancestral shrines? Those were weighty matters.

He wanted to go and converse with his maternal uncle—Soga no Emishi—and with the ministers, but there was no good chance, and so he had kept quiet, but he did remember, years ago, when he went to visit his sick uncle, and he stayed at the nearby temple of Toyoura, the nunnery built on the site of Kashikiya Hime’s palace. At that time she sent him a message via Yakuchi no Shibime, who said that his uncle, the Oho-omi, was constantly worried for him. After the sovereign’s death, wouldn’t the succession fall to him? And so he should be watchful and take care of himself.

To Prince Yamashiro, the matter seemed clear, but he emphasized that he did not necessarily covet the realm, only declared what he had heard, calling to witness the kami of Heaven and Earth. Therefore, he wanted to make sure that he correctly understood her majesty’s dying words.

And so he praised the ministers for always addressing the sovereign without bias, and asked that they go back to his uncle, Soga no Emishi, and convey what he had told them.

Prince Hase, another son of Prince Umayado by another mother, and half-brother to Prince Yamashiro, separately sent for Nakatomi no Muraji and Kawabe no Omi. He told them how both he and his father—and his brother—came from the Soga family, and that they relied upon it heavily. Therefore he asked that they do not speak lightly of the matter of succession. He then sent for the ministers, including Prince Mikuni and Sakurawi no Omi and emphasized that he wanted to make sure there was an answer from his uncle.

Emishi’s reply, sent via his own intermediaries, was that he had previously said all that he had to say and nothing else. However, how should he presume to choose, himself, between one prince or the other?

And so one can imagine the tension. Soga no Emishi wanted the court to place Prince Tamura on the throne, but clearly Prince Yamashiro thought that Kashikiya Hime meant for him to succeed her. Nobody appears to have fully corroborated either side’s telling of the sovereigns last words—in fact, even in the Nihongi there are several different versions that show up, including a variation at the end of her reign and the variations in the telling of the start of the next. Was Prince Yamashiro remembering or understanding the words correctly? Were others distorting them for political gain?

A few days after the ministers left Ikaruga, Prince Yamashiro sent Sakurawi no Omi once again to Soga no Emishi. He again reiterated that he had only reported what he had heard, and that he did not want to go up against his own uncle. However, Soga no Emishi was feeling ill, and was unable to talk with Sakurawi no Omi, who presumably left the message with his attendants and then left.

The next day, feeling in better spirits, Soga no Emishi sent for Sakurawi no Omi, Prince Yamashiro’s messenger, as well as various ministers to go and carry a message back to Prince Yamashiro. He started by abasing himself, claiming that from the time of Ame Kunioshi, aka Kinmei Tennou, until now, the end of the reign of Kashikiya Hime, the ministers had all been wise men. However, he questioned his own rank, stating that he mistakenly held rank above everyone else merely because good men were hard to find. But because of this lack of wisdom, he could not settle the question of succession. That was, of course, a grave matter, and not one to be discussed through intermediaries—despite the fact that he was expressly using intermediaries. And so he agreed, despite the fact that he was of more advanced years, to travel up to Ikaruga to speak directly with Prince Yamashiro so that there would be no misunderstanding of her majesty’s words. This was totally the case and not at all because he had any private views.

At the same time, Soga no Emishi sent Abe no Omi and Nakatomi no Muraji to his own paternal uncle, Sakahibe no Omi no Marise, and asked him one more time “Which Prince shall be made sovereign?” Clearly he was hoping Marise would swing to his side and agree to support Prince Tamura, with the hope that he could therefore cut off any dissent.

Marise answered that he had already given his answer in person, and that he had nothing more that he wanted to say. He then went off in a huff, upset that he was even being asked a second time. He clearly saw the question as an attempt by his nephew to get him to change his answer.

Now as all of this was going on, the Soga family was gathering all of their clan to construct the tomb for Soga no Umako—perhaps referring to kofun known today as Ishibutai. Soga no Umako had passed away some time ago, but perhaps had been buried in a temporary mound, and only now was his final tomb being completed. Marise’s job was to tear down the sheds at the tomb, which he apparently did, but then immediately retired to the nearby Soga farm-house—likely meaning a house out by the rice paddies rather than the main Soga compound only a slightly further walk away. Once there, Marise refused to do any more work, protesting the way his nephew was treating him.

This temper tantrum pissed of Soga no Emishi to no end. He sent to Marise two messengers of Kimi and Obito rank—as opposed to the high ministers sent to Prince Yamashiro. A rough translation of the message goes as follows:

“I know your evil speeches, but by reason of our relationship of elder and younger brother, I cannot injure you. If others are wrong and you are right, I shall oppose them and follow you. But if others are right and you are wrong, I will oppose you and follow them. Then, if you should eventually disagree with me, there will be a breach between us and there will be fighting in the land. If that happens, future generations will say that you and I brought the country to ruin. So be careful and do not allow a rebellious spirit to rise up.”

Marise was still having none of it, and to add insult to injury he left to stay at Prince Hase’s palace in Ikaruga, basically shacking up with the pro-Yamashiro faction.

Soga no Emishi just got more upset over this blatant and public display of loyalty to the Yamashiro cause and sent ministers to Prince Yamashiro demanding that they hand over Marise. These messengers made the case that Marise was disobedient to Soga no Emishi, the head of the Soga house, and was hiding in the palace of Prince Hase. Soga no Emishi requested that they hand Marise over so that he could examine why Marise was doing this, though that was likely just a polite reason so that Emishi could lock him up or worse until the succession crisis was concluded.

Prince Yamashiro answered that Marise had always been a favorite of her majesty, and that he had only come to Ikaruga for a short visit, nothing political. How could he hope to stand up against Soga no Emishi? And so he asked that no blame come to him.

At the same time, Prince Yamashiro spoke to Marise and warned him that, however touched Yamashiro might have been to have Marise come to seek them out, and despite the gratitude he owed for Prince Umayado, Marise’s actions threatened the peace of the realm. The way things were headed, if Marise stayed at Ikaruga, then it would have given a pretense for Soga no Emishi and his supporters to storm the palace and take him by force, likely bringing the political dispute over succession to a head that would break out into actual warfare and martial conflict.

Moreover, Prince Yamashiro’s father, Prince Umayado, had always told his children to avoid all evil and practice good of every kind; and that had become Prince Yamashiro’s constant rule. Because of that, although Prince Yamashiro may have had his own private opinions on the matter, he was patient and not angry. He refused to set himself up against his uncle. Therefore he urged Marise to not be afraid to change his answer in support of Prince Tamura; he should yield to the many and not retire from public life. The various high officials present likewise urged Marise to listen to Prince Yamashiro and to do as he suggested.

Marise, finding no support for going up against his uncle, Soga no Emishi, finally gave in. He burst out weeping and went home, where he stayed secluded for more than 10 days. During that time, his one supporter, Prince Hase, suddenly took ill and passed away.

With Prince Hase dead, Soga no Emishi decided to move against Marise. He raised troops and sent them to Marise’s house. Hearing they were coming, and knowing he had nowhere left to turn, Marise and his second son, Aya, sat in chairs outside the gate to their home, waiting for the troops to arrive. When they got there, Mononobe no Ikuhi was made to strangle them, and they were both buried together.

Marise’s eldest son, Ketsu, had tried to escape this fate. He fled to the Worship Hall of nunnery—perhaps Toyoura temple?—where he’d had some assignations with a couple of the nuns. However, one of the nuns was apparently jealous and told the troops where he was. They stormed the nunnery, but Ketsu slipped their grasp and headed to Mt. Unebi. The troops searched the mountain thoroughly, and eventually Ketsu found himself hemmed in on all sides, with nowhere left to turn. Rather than be taken and killed by the troops, he decided to take his own life, stabbing himself in the throat.

When people heard about all of this, they wrote a song. It goes:

UNEBIYAMA / KOTACHI USUKEDO / TANOMIKAMO

KETSU NO WAKUGO NO / KOMORASERIKEMU

Which Aston Translates as:

On Mt. Unebi / Though thin are the trees, / May there not be some trust in them?

The youth Ketsu / Seems to have hidden there.

Following the death of Marise, it seems there were none left that were promoting Prince Yamashiro’s ascension—even he seems to have quit arguing for it. Whether or not Soga no Emishi ever came to talk to him is not recorded. Instead they mention that on the 4th day of the first month of 629, Soga no Emishi and the ministers offered the royal seal to Prince Tamura. Although Prince Tamura initially refused, as appears to have been de rigeur for such things, the ministers persisted. Prince Tamura claimed that it was a weighty matter and that he was wanting in wisdom, and the Ministers responded that he was the favorite of Kashikiya Hime, and that both the spiritual and physical realms would turn their hearts to him. Therefore he should continue the royal line. And so, later that day he took the throne. He is also known as Joumei Tennou.

And so that is the story of the succession crisis that followed the death of Kashikiya Hime, and how Tamura, aka Joumei Tennou, came to the throne. Soga no Emishi would continue to exert considerable authority over the throne, and there would be more changes coming to the government and to the state. At the same time, Prince Yamashiro was still out there, meaning that there was at least one other possible claimant to the throne still out there. We’ll address that in our upcoming episodes.

Until then, thank you for listening and for all of your support.

If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

Thank you, also, to Ellen for her work editing the podcast.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Kiyotaka Tanikawa, Mitsuru Sōma (2004). On the Totality of the Eclipse in AD 628 in the Nihongi. Publications of the Astronomical Society of Japan. Vol. 56, Issue 1, 25 February 2004. pp. 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1093/pasj/56.1.215

Piggott, Joan R. (1997). The Emergence of Japanese Kingship. Stanford, Calif : Stanford University Press. ISBN9780804728324

Kiley, C. J. (1973). State and Dynasty in Archaic Yamato. The Journal of Asian Studies, 33(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/2052884.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4