Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

Here we go, starting our foray into the reign of Kashikiya Hime no Ōkimi, aka Suiko Tennō, and we start with looking at the relationship between the archipelago and the continent, particularly the states on the Korean Peninsula.

Dramatis Personae

I’m not going to cover everyone in this summary. Partly because some of the names are slightly familiar, but not so much that the individual is the point—at least not yet. There are a few exceptions, however,

Naniwa no Kishi

There are several individuals this time around that are known as either “Kishi” or “Naniwa no Kishi”, and mention of them goes back at least the reign of Wakatakiru, aka Yūryaku Tennō. There we see listed a “Naniwa no Kishi” and “Hitaka no Kishi”. In this case, “Kishi” seems to be like a kabane. However, by this point, the early 7th century, it seems like “Kishi” is used just like a name. It is possible it evolved into a name, over time, and I’ll try to look into that a bit more, just know that we are going to have some questions around the Naniwa no Kishi.

Kanroku / Kwalleuk

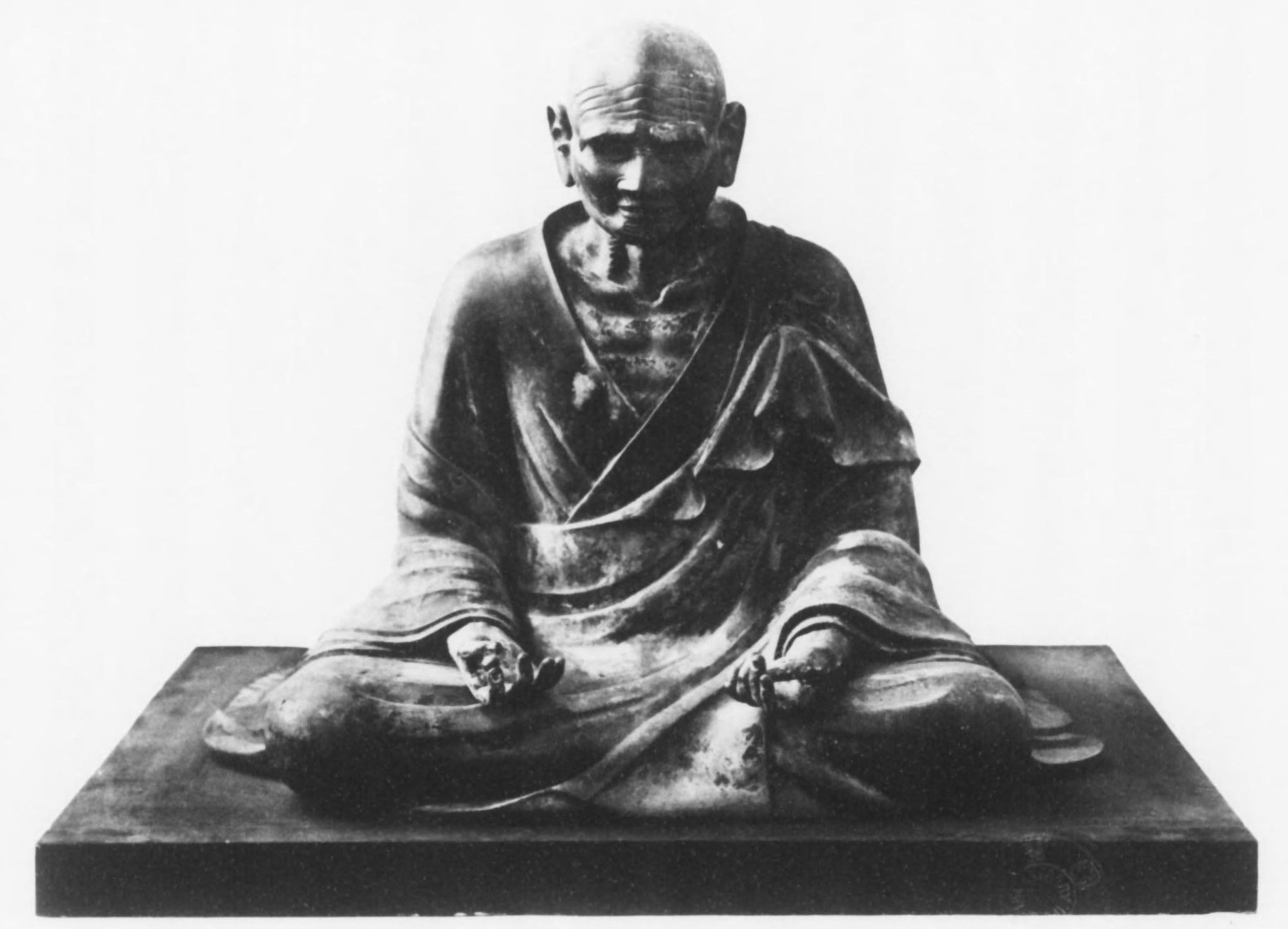

Kanroku—Aston translates his name into modern Korean as Kwalleuk—was a priest from Baekje and is seen as one of the teachers of Shōtoku Taishi.

Prince Kume

I mention this in the episode, but “Kume” means “Army” (though the characters they use are more like “Come” and “Eye/See”). Not much is known, other than the fact that he was recorded as a royal prince and he eventually was placed in charge of the army.

Tamahe no Kimi

The older brother of Umayado and Kume. Again, we don’t know much about him at this point, other than what is in the genealogical records. This appears to be the same person elsewhere listed as “Maruko”.

Magpies

As noted in the episode, magpies are not native to Japan. That said, there are two different types that the word the Japanese used could be used for . This first is the Eurasian Magpie (pica pica) and the other is the Oriental, or Chiense, Magpie (pica sericus). Although the magpies are not native to the archipelago, stories of them as auspicious birds no doubt came across.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is Episode 94: Magpies, Buddhism, and the Baekje Summer Reading Program

This is one of a multi-part series discussing the late 6th and early 7th centuries during the reign of Kashikiya Hime, aka Suiko Tennou. Last episode, Episode 93, I did a very quick overview of just what is going on and some of the players involved. This episode I want to start deep diving into some of the topics, and we’re going to start with looking at the relationship between Yamato and the Continent, primarily, but not exclusively, through their relationships, the gifts and tribute that was going back and forth, and immigration—primarily from Baekje and Silla—and the importation of new ideas, not just Buddhism. This in turn would would eventually lead to a formal change in the way that the Yamato state governed itself and how it came to see itself even as an equal to that of the Sui court, which had unified the various kingdoms of the Yangtze and Yellow River Basins in the area of modern China.

To begin, we’ll go back a bit, because this dynamic isn’t simply about Kashikiya Hime, Soga no Umako, or any one, single figure—though that is often how it is portrayed. To start with, let’s cover some background and what we know about the archipelago and the continent.

As we went over many, many episodes back, the early Yayoi period, prior to the Kofun period, saw a growth in material cultural items that were from or quite similar to those on the Korean peninsula. There had been some similarities previously, during the Jomon period, but over the course of what now looks to be 1200 to 1300 years, the is evidence of people going regularly back and forth across the straits. It is quite likely that there were Wa cultural entities on both sides in the early centuries BCE, and there are numerous groups mentioned on the Korean peninsula, presumably from different ethno-linguistic backgrounds, though typically only three areas get much focus: The Samhan, or three Han, of Mahan, Byeonhan, and Jinhan. Later this would shift to three Kingdoms: Baekje, Silla, and Goguryeo, and they would get almost all of the press. Still, we know that there were groups like the Gaya, or Kara, confederacy, and likely other small, eventually isolated groups that did not have their stories written down anywhere, other than mentions in the Chronicles of Japan or of one of the other three major Kingdoms of the peninsula.

These groups continued to trade with the continent, and as the archipelago entered the period of mounded tombs, they were doing so as part of a larger mounded tomb cultural area that included both the archipelago and the Korean peninsula: First the funkyubo, which is to say burial mounds, with multiple burials, and then the kofun, the singular tomb mounds for an individual and possibly their direct relatives. This tradition reached its apex with the distinct zenpo-koen, or round-keyhole style, kofun, an innovation that was rooted in continental practice but at the same time distinctly a part of the archipelago.

Many artifacts came over throughout this period, and a fair number of them came with a new innovation: writing. There is debate over the earliest forms of “writing” to be found in the islands, with evidence of characters on pottery being questioned as to its authenticity. However, it is hard to question the writing that appeared on the early bronze mirrors and other such artifacts that showed up.

Early writing on the archipelago is more decorative or even performative—crude attempts to copy existing characters that often demonstrate a lack of understanding, at least by the artisans that were making various elite goods. Though, based on the fact that even obvious forgeries with nonsense characters made their way into tombs as grave goods, we can probably assume that most of the elites were not too concerned with writing, either, other than for its decorative, and possibly even talismanic qualities.

In the fourth and fifth centuries, this began to change. We have specialists and teachers coming over to the archipelago, often there as tutors for the royal Baekje princes who were apparently staying in Yamato as part of a diplomatic mission. No doubt some Yamato elites began to learn to read and write, but even at this point it seems to have been more of a novelty, and for several centuries reading and writing would seem to have remained largely the purview of educated immigrant communities who came to Yamato and set up shop. Though, along with things like the horse, writing may have nonetheless assisted Yamato in extending its authority, as speech could now, with a good scribe, be committed to paper or some other medium and then conveyed great distances without worry about something begin forgotten.

So, at this point, writing appears to mostly be utilitarian in purpose. It fills a need. That said, we have discussion of the Classics, and as reading and writing grew, exposure to writings on philosophy, religion, and other topics expanded.

After all, reading meant that you were no longer reliant on simply whom you could bring over from the continent. Instead, you could import their thoughts—or even the thoughts of humans long dead—and read them for yourself. In the early 6th century, we see Baekje sending over libraries worth of books. These are largely focused on Buddhist scriptures, but they also include other works of philosophy as well. It is unclear to me how much the evangelical nature of Buddhism contributed to this spread. Buddhism exhorts believers to share the Buddha’s teachings with all sentient beings. Even during the Buddha’s lifetime, his disciples would go out and teach and then gather back with their teacher during the rainy season.

Buddhist teachings, coming over in books—the sutras—came alongside of other writings. There were writings about philosophy, about medicine, and about science, including things that we might today consider magical or supernatural. Those who knew how to read and write had access to new knowledge, to new ideas, and to new ways of thinking. We can see how all of this mixed in the ways that things are described in the Chronicles. For example, we see that many of the rulers up to this point have been described in continental terms as wise and sage kings. Now, as Buddhism starts to gain a foothold, we see Buddhist terminology entering in to the mix. In some ways it is a mishmash of all of the different texts that were coming over, and it seems that things were coming more and more to a head.

In addition, there were things going on over on the continent as well, and this would come to also affect the archipelago. For one thing, this was a period of unification and consolidation of the various state polities. Baekje and Silla had been consolidating the smaller city-states under their administration for some time, and in 589 the Sui dynasty finally achieved what so many had tried since the time of the Jin—they consolidated control over both the Yangtze and Yellow River basins. They set up their capital, and in so doing they had control of the largest empire up to that point in the history of East Asia. The Sui dynasty covered not only these river basins, but they also had significant control over the Western Regions, out along the famous Silk Road.

The Sui could really make some claim to being Zhongguo, the Middle Kingdom, with so many of the trade routes passing through their territory. They also controlled the lands that were the source of so much of the literary tradition—whether that was the homelands of sages like Confucius, or else the gateway to India and the home of Buddhism. It is perfectly understandable that those states in the Sui’s orbit would enter a period of even further Sinification. For the archipelago this was likely through a lens tinted by their intermediaries on the Korean peninsula, but even they were clearly looking to the Sui and adopting some of the tools of statecraft that had developed over in the lands of the Middle Kingdom.

During the early years of the Sui, Yamato had been involved in their own struggles, and at the end of the previous reign Yamato had an army in Tsukushi poised to head over and chastise Silla for all that they had done to Nimna, but then Hasebe was assassinated, and it is unclear what actually happened to that expedition. Yamato started gathering an army in 591, and Kishi no Kana and Kishi no Itahiko were sent to Silla and Nimna, respectively, as envoys, and then we are told that in 595 the generals and their men arrived from Tsukushi. Does that mean that they went over to the peninsula, fought, and then came back from Tsukushi? It is all a little murky, and not entirely clear to me.

Rather, we are told that in 597 the King of Baekje sent Prince Acha to Yamato with so-called “tribute”—the diplomatic gifts that we’ve discussed before, re-affirming Baekje and Yamato’s alliance. Later that same year, Iwagane no Kishi was sent to Silla, so presumably Yamato and Silla relations had improved. Iwagane no Kishi returned back some five months later, in 598, and he offered a gift from the Silla court of two magpies to Kashikiya Hime. We are told that they were kept in the wood of Naniwa, where they built a nest in a tree and had their young.

Aston notes here that magpies are plentiful on the continent but not in Japan. Indeed, their natural range is noted across eastern China and up through the Amur river region, as well as a subspecies up in Kamchatka, and yet it seems like they didn’t exactly stray far from the coast. In modern Japan, the magpie, is considered to be an invasive species, and the current populations likely were brought over through trade in the late 16th century, suggesting that this initial couple of birds and their offspring did not exactly work out. Even today magpies are mostly established in Kyushu, with occasional sightings further north—though they have been seen as far north as Hokkaido. Perhaps Naniwa just was not quite as hospitable for them. There is also the possibility that the term “magpie” was referencing some other, similar bird. That is always possible and hard to say for certain.

That said, it is part of a trend, as four months later, in the autumn of 598, a Silla envoy brought another bird: this time a peacock. Not to be outdone, apparently, a year later, in the autumn of 599, Baekje sent a veritable menagerie: a camel, two sheep, and a white pheasant. Presumably these were sent alive, though whether or not there was anyone in Japan who knew how to take care of them it is unclear. I can only imagine what it must have been like to have such animals on board the ship during the treacherous crossing of the Korea strait—for all we know there were other exotic gifts that were likewise sent, but these are the only ones that made it.

And if this sounds far-fetched, we have plenty of evidence of the exotic animal trade. Animals such as ostriches, and possibly even a giraffe or two, were somehow moved all the way from Africa along the silk road to the court in Chang’an.

There were also “tribute” gifts sent from parts of the archipelago, though I suspect this was quite different from the diplomatic gifts shared between states. For example, there was a white deer sent to Kashikiya Hime from the land of Koshi in the winter of 598. It was no camel or magpie, but white or albino animals—assuming that wasn’t their normal color—were considered auspicious symbols.

Also, in 595 there was a huge log that washed ashore in Awaji. A local family hauled it up and went to use it as firewood when they noticed that it gave off a particularly sweet smell. Immediately they put out the fire, as they suddenly realized what they had: it was a log of aloeswood. Aloeswood is well known as one of the most highly prized aromatic woods, and it famously does not grow in Japan. In fact, it is a tropical wood, growing in Southeast Asia. For a log to have washed ashore is almost unbelievable—perhaps it was part of a trade shipment that sank. It isn’t impossible that a log somehow fell, naturally, into the ocean and followed the currents all the way up to Japan, which would have been quite the journey.

And so, with such a rare gift, the people offered it up to Kashikiya Hime. This was probably the best course of action. They could use it for themselves, but that likely wouldn’t have done much other than help perfume the air for a time. Or they could have tried to sell it—but given the rarity, I’m sure there would have been questions. In both cases, I suspect that they would have been at risk of some elite getting wind and deciding that they should just take it for themselves. By offering it to the court, publicly, they received the credit for it, at least—and it probably put them in favor with the court at least for a little while.

Logs like this would be treated with immense respect. Small pieces would be taken, often ground down and used sparingly. A piece much like this called “Ranjatai” came over as a gift from the Tang dynasty in the 8th century, and was later preserved at Todaiji in the 8th century, and is still there as part of the Shosoin collection.

The story of this particular one is interesting in that knowledge of aloeswood and the tradition of scent appreciation likely came over from the continent, probably from the Sui and Tang dynasties, as part of the overall cultural package that the archipelago was in the midst of absorbing.

Despite the apparently good relations indicated by gifts like magpies or peacocks, it is clear there were still some contentions with Silla, especially given that nobody had forgotten their takeover of Nimna, and it didn’t help that in 600, we are told that Silla and Nimna went to war with each other--again. It isn’t clear just how involved Yamato was in this, if at all—by all accounts, Nimna has already been under Silla control. Was this a local rebellion? An attempt by Yamato and Baekje to split it off? Or something else? Or is it just a fabrication to justify the next bit, where we are told that Kashikiya Hime sent an army of 10,000 soldiers under the command of Sakahibe no Omi as Taishogun and Hozumi no Omi as his assistant, the Fukushogun? They crossed the waters over to Silla and laid siege to five of Silla’s fortresses, forcing Silla to raise the white flag. The Nihon Shoki claims that Silla then ceded six fortified places: Tatara, Sonara, Pulchikwi, Witha, South Kara, and Ara.

Since Silla submitted, the Yamato troops stopped their assault and Kashikiya Hime sent Naniwa no Kishi no Miwa to Silla and Naniwa no Kishi no Itahiko to Nimna to help broker some sort of peace. Interestingly, this seems quite similar to the account of 591, when they sent “Kishi no Itahiko”, with no mention of Naniwa. Presumably it is the same individual, and I have to wonder if it isn’t the same event, just relocated and duplicated for some reason.

A peace was brokered, and the Yamato troops departed, but it seems that Silla was dealing in something other than good faith: no sooner had the Yamato troops gotten back in their boats than Silla once again invaded Nimna, again.

I’d like to stress that there is no evidence of this at all that I could find in the Samguk Sagi, and it is possible that some of this is in the wrong section, possibly to simply prop up this period, in general. However, it is equally as likely that the Samguk Sagi simply did not record a loss to Yamato—especially one that they quickly overturned, setting things back to the status quo. As such, the best we can say is that Silla and Yamato around this time were less than buddy buddy.

With Silla going back on their word, Yamato reached out to Goguryeo and Baekje in 601. Ohotomo no Muraji no Kurafu went to Goguryeo, while Sakamoto no Omi no Nukade traveled to Baekje. Silla was not just waiting around, however, and we are told that Silla sent a spy to Yamato, but they were arrested and found out in Tsushima. They arrested him and sent him as tribute to the Yamato court.

We are told that the spy’s name was “Kamata”, and he was banished to Kamitsukenu—aka the land of Kenu nearer to the capital, later known as Kouzuke. And there are a few things about this story that I think we should pull on.

First off, that name: Kamata. That feels very much like a Wa name, more than one from the peninsula. We aren’t told their ethnicity, only whom they were working for, so it may have been someone from Wa, or possibly that is just the name by which they were known to the archipelago. There likely were Wa who were living on the peninsula, just like there were people from Baekje, Silla, and Koguryeo living in the archipelago, so that’s not out of the question. Furthermore, it would make sense, if you wanted to send someone to spy on Yamato, to use someone who looked and sounded the part.

The punishment is also interesting. They didn’t put him to death. And neither did they imprison him. In fact, I’m not sure that there would have been anywhere to imprison him, as there wasn’t really a concept of a “prison” where you just lock people up. There may have been some form of incarceration to hold people until they could be found guilty and punished, but incarceration as a punishment just doesn’t really come up. Instead, if you wanted to remove someone, banishment seems to have been the case—sending them off somewhere far away, presumably under the care of some local official who would make sure that they didn’t run off. Islands, like Sado Island, were extremely useful for such purposes, but there are plenty of examples where other locations were used as well.

They probably could have levied a fine, as well, but that seems almost pointless, as he would have been free to continue to spy on Yamato. Instead they sent him about as far away from Silla and Silla support as they could send him.

This also speaks to the range of Yamato’s authority. It would seem that Tsushima was at least nominally reporting to Yamato, though given that he was sent as “tribute” to the court, that may indicate that they still had some level of autonomy. And then there must have been someone in Kamitsukenu in order to banish someone all the way out there, as well.

Of course, given all of this, it is hardly surprising that Yamato was back to discussing the possibility of making war with Silla again. And so, in the second month of 602, Prince Kume was appointed for the invasion of Silla, and he was granted the various “Be” of the service of the kami—possibly meaning groups like the Imbe and the Nakatomi, along with the Kuni no Miyatsuko, the Tomo no Miyatsuko, and an army of 25,000 men. And they were ready to go quickly—only two months later they were in Tsukushi, in the district of Shima, gathering ships to ferry the army over to the peninsula.

Unfortunately, two months later, things fell apart. On the one hand, Ohotomo no Muraji no Kurafu and Sakamoto no Omi no Nukade returned back from Baekje, where they likely had been working with Yamato’s allies. Kurafu had been on a mission to Goguryeo and Nukade had been sent to Baekje the previous year. However, at the same time, Prince Kume fell ill, and he was unable to carry out the invasion.

In fact, the invasion was stalled at least through the next year, when, in about the 2nd month of 603, almost a year after Prince Kume had been sent out, a mounted courier brought news to Kashikiya Hime that he had succumbed to his illness. She immediately consulted with her uncle, Soga no Umako, and the Crown Prince, Umayado, and asked them for their counsel. Ultimately, she had Kume’s body taken to Saba in Suwo, out at the western end of the Seto Inland Sea side of western Honshu, modern Yamaguchi Prefecture, where the prince was temporarily interred, with Hashi no Muraji no Wite, possibly a local official, overseeing the ceremony. Later, Wite’s descendants in the region were called the Saba no Muraji. Kume was finally buried atop Mt. Hanifu in Kawachi.

A quick note here about time. It is sometimes difficult to figure out just what happened when. This is all noted for the fourth day of the second month of 603. Clearly it didn’t all happen in one day, so what actually happened on that day? Remember, Kume fell ill in the 6th month of 602, and we are now in the 2nd month of the following year. So did he fall ill and then was wasting away for 8 months before he passed away? Or is this the date when the court learned of his death? Or is it the date when his body was finally buried? There is a lot going on, and they don’t exactly provide a day-to-day. My general take is that this is when the news arrived at the court, which is when there would have been a court record, while the rest was likely commentary added for context, even if it happened much later.

In addition, this whole thing holds some questions for me, not the least the name of this prince: Kume. Presumably, Kume was a full brother to none other than the Crown Prince, Prince Umayado. He was also a son of Princess Anahobe and the sovereign, Tachibana no Toyohi, and we have seen then name “Kume” before as a name, or at least a sobriquet, for someone in the royal family. However, it also means “army”, which seems surprisingly on the nose, given that all we are given about him is that he was supposed to lead an army. It makes me wonder if this wasn’t one of those half-remembered stories that the Chroniclers included without all of the information. Then again, maybe Kume really was his name, and this is all just a coincidence.

I also would note that it was not typical to have a royal prince leading an expedition like this. Typically, the taishogun would be someone from an influential family, but not a member of the royal family, themselves. That this army was being led by a royal prince also seems to speak to how this was seen as significant. Perhaps that is why, when Kume passed away, they chose as his replacement his older brother: Tahema. [Look up more on Tahema and if I can find out about him]

Tahema was selected to take over for his younger brother on the first day of the 4th month of 603, and 3 months later, on the 3rd day of the 7th month, he was leaving out of Naniwa. He didn’t get very far, however. Tahema embarked on this adventure along with his own wife, Princess Toneri. We’ve seen this in past episodes, where women were in the camp alongside their husbands, directly supporting the campaigns. Unfortunately, in this case, Princess Toneri died shortly into their journey, at Akashi. This is recorded as only three days after they had departed, which likely means it happened quickly. They buried her at Higasa Hill, but Tahema, likely grieving his loss, returned, and never carried out the invasion.

Five years later, things may have improved with Silla, as there were a number of immigrants—we are only told that they were “many persons”—came to settle in Japan. What isn’t noted is whether or not this was of their own volition. What forces drove them across from the peninsula? Did they realize that there were opportunities to come and provide the Yamato elites with their continental knowledge and skills? Were they prisoners of war? If so, where was the war? Or were they fleeing conflict on the peninsula? Perhaps political refugees? It isn’t exactly clear.

While things were rocky with Silla, relations seem to have been much better with the Baekje and Goguryeo. While exotic animals may have been the gift of choice in the early part of the period, by 602, Baekje and Goguryeo were both sending gifts of a different sort. These were more focused on spiritual and intellectual pursuits. And so, in 602, a Baekje priest named Kwalleuk—or Kanroku, in the Japanese pronunciation—arrived bringing books on a number of different subjects, which three or four members of the court were assigned to study. We don’t know exactly what the contents of each book was, but based on what we generally know about later theories, we can probably make some educated guesses that much of this was probably based on concepts of yin and yang energies. Yin and yang, were considered primal energies, and at some point I will need to do a full episode just on this, but during the Han dynasty, many different cosmological theories came together and were often explained in terms of yin and yang. So elemental theory is explained as each element has some different portion of yin and yang, and similarly different directions, different times of day, and different times of the year were all explained as different proportions of yin and yang energies, which then contributed to whether certain actions would be easier or more difficult—or even outright dangerous.

The book on calendar-making, or ”koyomi”, was assigned to Ohochin, whose name suggests that he may have been from a family from the continent, and he was the ancestor of the Yako no Fumibito. Calendar-making was considered one of the more important roles in continental sciences, although it never quite took off to the same degree in Yamato. Still, it described the movement of the stars and how to line up the lunar days with various celestial phenomena. It also was important for understanding auspicious and inauspicious days, directions, and more—arts like divination, geomancy, and straight up magic would often provide instructions that required an understanding of the proper flow of yin and yang energies, as represented by the elements, and expressed on the calendar in terms of the elemental branch and stem system, with each day being related to a given element in an either greater or lesser capacity, usually related as the elder or younger brother. Events might be scheduled to take place, for instance, on the first rat day of the first month, and so the calendar maker would be the one to help determine when that would be. Also, since the solar and lunar calendars were not in synch, there would occasionally be a need for a “leap month”, often known as an extra-calendrical month, which would typically just repeat the previous month. This would happen, literally, “once in a blue moon”, an English expression referring to a solar month with two full moons. In fact, we just had one of those last month, in August of 2023.

This isn’t to say that the archipelago didn’t have a system of keeping track of seasons, etc. Clearly they were successfully planting and harvesting rice, so they had knowledge of roughly what time it was in the year, though there are some thoughts that a “year” was originally based on a single growing period, leading to two or three “years” each solar year. Either way, farmers and others no doubt knew at least local conditions and what to look for regarding when to plant, and when to perform local ceremonies, but this was clearly a quote-unquote, “scientific” approach, based on complex and authoritative sounding descriptions of yin and yang energies.

Closely related to the calendar-making studies, another book that the Baekje priest Kwalleuk brought over was one on Astronomy, or “Tenmon”, a study of the heavens, which was studied by Ohotomo no Suguri no Kousou. For perhaps obvious reasons, astronomy and calendar-making were closely aligned, since the change in the stars over the course of the year would often have impacts on the calendar. However, this was also likely very closely aligned with something akin to astrology, as well, following the celestial paths of various entities, many of those being things like planets. If you aren’t aware, planets, though they often appear in the sky as “stars”, have apparently erratic movements across the heavens. The stars generally remain fixed, and from our perspective appear to “move” together throughout the year. Planets, however, take funky loop-de-loop paths through our sky, as they, like the earth, are also orbiting the sun. Furthermore, different planets orbit at different speeds. All of this leads to some apparently strange movements, especially if you envision the sky as a round dome over a flat earth. There are also other phenomenon, from regular meteor showers to comets, and even eclipses, all of which were thought to have their own reasons. Some of these were considered natural—neither auspicious nor inauspicious—while others were thought to impact the flow of yin yang energy on the earth, thus potentially affecting our day-to-day lives.

Kousou was apparently trying to get the special bonus for the summer reading program, because he also studied another book that came over from Baekje on a subject that Aston translates as “Invisibility”, or “tonkou”. This is a little less obvious an explanation. I don’t think that they were literally studying, ninja-style, how to not to be seen. In discussions of kami we’ve talked in the past about visible kami and, thus, conversely, invisible kami. It appears to be based on a type of divination to help better understand auspicious and inauspicious signs, and is based on a blend of various theories, again connected to a large yin-yang theory.

Finally, there was another volume that was studied by Yamashiro no Omi no Hinamitsu that Aston translates as straight up “magic”, or “houjutsu”. Of course, in the worldview at the time, Magic was just another science that we didn’t understand. By understanding the flow of yin and yang, one can affect various things, from helping cure disease and heal the sick to causing calamity, even to the point of possibly learning the secrets of immortality.

Much of this would fall into the terms “onmyoudou”, the way of Yin and Yang, and there had been some work on that introduced earlier. That it was being introduced by a Buddhist priest demonstrates what I was saying earlier about just how interconnected it all was.

Other Buddhist gifts were much more straightforward. In 605, for instance, the king of Goguryeo sent 300 Ryou of what they call “yellow metal”, possibly an admixture of gold and copper, for a Buddhist image. Five years later they sent two priests. One of them, Tamchi, is said to have known the Five Classics, that is the Confucian classics, as well as how to prepare different colored paints, paper, and ink.

All of this is interesting, but it is the usual suspects. Yamato had been siphoning off culture and philosophy from the states and kingdoms of the Korean peninsula for some time, and in that time, they began to adopt various continental practices. In later centuries, much of this would be attributed to the work of Shotoku Taishi, aka Prince Umayado, especially the transmission of Buddhist thought, although for the most part we haven’t actually seen a lot of that in the Chronicles themselves, which we’ll get to.

However, later stories paint him as one of the main forces pushing for reform in the court, especially when they would eventually push for a new, 17 article constitution, based on principles pulled from a variety of sources—both Buddhist and Han philosophical foundations. Along with that constitution, the court also instituted a 12 rank system for court ministers. This ranking system would remain in place, eventually replacing entirely the kabane system that ranked individuals based on their family in favor of ranking one for their individual achievements.

Furthermore, it wasn’t just a status symbol. Rank would come into play in all aspects of courtly life, from the parts of the palace you were allowed to be in, the kinds of jobs you could do, and even the amount that you were paid for your service, making the families of the land part of and dependent on the bureaucracy.

And with such a system in place, there was only one natural thing for it: The Yamato court would reach out beyond the Korean peninsula and go directly to the source. They would send envoys to the court of the Sui Emperor himself and establish relations with the Middle Kingdom directly, leading to one of the most famous diplomatic incidents in all of the early Japanese history.

And that is where I’m going to have to leave it for now, because once we get into that rabbit hole we are going to have a whole other episode. And so now we are fully grounded in our foundation. We can see Yamato importing people and also ideas from the continent, through the peninsula, and those ideas are taking root. They are causing changes, at least at the Yamato court, but those changes would eventually make there way throughout society, and forever change Japan and even how they see themselves. The lens of what is commonly seen as Buddhist and Confucian thought would be a powerful tool that would shape the ideas to come.

Until next time, then, thank you for listening and for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Lurie, D. B. (2011). Realms of Literacy: Early Japan and the History of Writing. Harvard University Asia Center. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1x07wq2

Como, Michael (2008). Shōtoku: Ethnicity, Ritual, and Violence in the Japanese Buddhist Tradition, ISBN 978-0-19-518861-5

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4