Previous Episodes

- March 2026

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we are digging into (pun intented) the material culture of Ōama’s court in Asuka. This will hopefully help us to have a better understand of what things may have looked like, but it also helps to understand changes more generally, at least at court. The move towards more continental styles of clothing and fashion demonstrate the popularity of continental ideas, which follows with the importation of Buddhism and new government structures. We might also have a better idea of the cultures that were particularly influential at this time.

Unfortunately, clothing is notorious ephemeral. Silk, in particular, deteriorates quickly, and many colors fade. Even various paintings that may have been created are no longer extant. As such, we have only a few key references from which to draw our conclusions.

Before delving much further into this blogpost, I would be remiss if I didn’t point out our own resources—though mostly focused on later fashion, you may find our section on Clothing and Accessories useful, which you can search for many of the terms we use.

Sources

There are a few different sources that we have for our understanding of clothing prior to the Nara period. All of these have their own problems, not the least of which being that each one is only a snapshot in time and even place. For example, is a 6th century image from modern Gunma prefecture relevant to Kyushu of the 6th century, let alone the 5th century? Without any contradictory evidence, we generally go with what we have.

Weizhi

The Wei Chronicles describe the clothing of the people in quite general terms that give us very little to go on, and which are not necessarily verifiable to the archipelago of the 3rd century:

All the men wear their topknots uncovered, with cotton cloths draped over their heads. Their clothes are made of wide strips of cloth tied together, with little or no sewing. The women's hair was tied in a knot, and their clothes were made like a single-layered robe with a hole in the middle, through which they stuck their heads.

It also contains mention of silk, as well as the use of tattoos.

Archaeological Evidence

Archaeologically speaking, we have pulled up certain things from sites, but nothing like a full set of clothes. There are fragments of cloth—or the impressions of cloth left in clay—which can help us understand the types of fabric, and even some of the dyes and colors that were used. We have examples of various ornaments and adornments that were a bit more sturdy—lacquered combs, shell bracelets, and the famous magatama come to mind. These come from a variety of sites, from the Yayoi through Kofun periods. It includes sites from different regions and time periods, including Yoshinogari, in Kyushu, clearly situated in the Yayoi period, to the Haruna eruption site of 550. There are also numerous items found in kofun, those ancient mounded tumuli, but that doesn’t always mean we have a clear idea of how they were worn, and by whom. In some cases we have multiple examples, but often we just have a single example of something here or there.

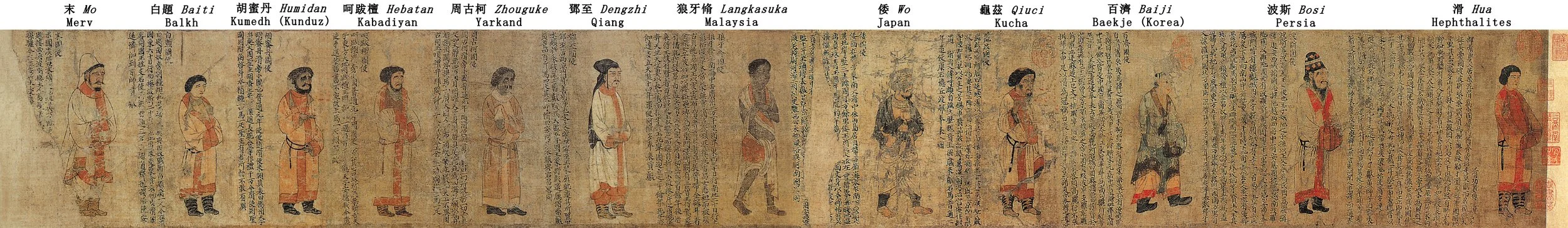

Embassies to the Liang Court

The Zhigongtu records embassies in the early 6th century. While the original is not extant, we have copies that were made. They show a variety of embassies from different countries including one from the “Wo” or “Wa”; the people of the Japanese archipelago. The images are great, but we have to wonder: how accurate are they? For one thing, they were likely drawn from memory, and the artist, the future Emperor Yuan of Liang, aka Xiao Yi, probably wasn’t examining their clothing too carefully. It is also possible that they were using the description in the Weizhi to guide their depiction.

Image (and updated conceptual drawing) of the “Wo” ambassador in the Liang Zhigongtu. Image from Wikimedia Commons. For another take on this outfit, see the Kyoto Costume Museum’s reconstruction.

Haniwa

Another source that we have are Haniwa figures. While the majority of the haniwa were simply clay cylinders, there were certainly others that were topped with bowls and various figures. Some of these were quite abstract, while others were fairly detailed. Most of the human figures show up only in the latter part of the kofun period, and styles vary greatly from region to region. It also isn’t like any of this is clearly labeled as to what they mean to represent, so we have to make some educated guesses based on what we know and context, but that could still be missing important pieces of information.

Based on those models, the Kyoto Costume Museum reconstructed them as follows:

Tenjūkoku Mandala

This embroidered mandala was made for Chūgūji, the temple built for Princess Anahobe, the mother of the famous Shōtoku Taishi, in 621. This mandala is thought to be from the 7th century.

Takamatsuzuka Kofun

Takamatsuzuka, a circular kofun in the Asuka area, is extremely important to our understanding of the clothing at the time for the intricate paintings which were in incredible condition when the tomb was first found and opened. The paintings depict eight women and eight men, which give us some idea of what people of the time wore. Or so we presume. The tomb shares characteristics with Goguryeo style tombs, and it is possible that the images are not depicting locals, but they do seem to accord well with the outfits in the mandala.

Click the below links to see images of the Kyoto Costume Museum’s reconstructions of these outfits:

Court Rank Color Chart

Click here for a color chart of the formal garments of the Asuka period onwards. Please note that the colors you see on the screen may be affected by many factors, just as dye lots for actual clothes wouldn’t always match exactly. So these are what we think they meant, but the color may be more of a range rather than just one, pure color.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is Episode 137: Courtly Fashion.

In the New Year’s ceremony, the court officials lined up in front of the Kiyomihara Palace, arranged by their relative court rank, dressed in their assigned court robes. The effect was impressive—the rows of officials painting the courtyard like the bands of color in a rainbow, albeit one with only a couple of hues. The fact that they were all wearing the same style of dress and black, stiffened gauze hats only added to the effect. The individual officers were all but lost in what was, at least in outward form, a single, homogenous machine of government, just waiting for the command of their monarch to attend to the important matters of state.

We are covering the reign of Ohoama no Ohokimi, aka Ama no Nunahara oki no mabito no Sumera no Mikoto, aka Temmu Tennou. Last episode we went over the changes he had made to the family titles—the kabane—as well as to the courtly rank system. For the former, he had consolidated the myriad kabane and traditional titles across Yamato into a series of eight—the Yakusa no Kabane. These were, from highest to lowest: Mabito, Asomi, Sukune, Imiki, Michinoshi, Omi, Muraji, and Inaki. By the way, you might notice that “Mabito” actually occurs in Ohoama’s posthumous name: Ama no Nunahara oki no mabito, which lends more credence to the idea that that kabane was for those with a special connection to the royal lineage.

Besides simplifying and restructuring the kabane, Ohoama also reformed the court rank system. He divided the Princely ranks into two categories: Myou, or Bright, and Jou, or Pure. For the court nobles the categories were:

Shou – Upright

Jiki – Straight

Gon – Diligent

Mu – Earnest

Tsui – Pursue

Shin – Advancement

Each category was further divided into four grades (except for the very first princely category, Myou, which was only two). Each grade was then further divided into large, “dai”, or broad, “kou”.

And this brings us to our topic today. Along with this new rank system, Ohoama’s administration also instituted a new set of court sumptuary laws. Some are vague in the record—we can just make assumptions for what is going on based on what we know from later fashion choices. Others are a little more clear. We’ll take a look at those sumptuary laws, particularly those that were directly associated with the new court rank system, but we’ll also look at the clothing styles more generally.

To start with, let’s talk about what we know about clothing in the archipelago in general. Unfortunately, fabric doesn’t tend to survive very well in the generally acidic soils of the Japanese archipelago. Cloth tends to break down pretty quickly. That said, we have fragments here and there and impressions in pottery, so we have some idea that there was some kind of woven fabric from which to make clothing out of.

And before I go too far I want to give a shout out to the amazing people at the Kyoto Costume Museum. They have a tremendous website and I will link to it in the comments. While there may be some debate over particular interpretations of historical clothing, it is an excellent resource to get a feel for what we know of the fashion of the various periods. I’ll also plug our own website, SengokuDaimyo.com, which has a “Clothing and Accessory” section that, while more geared towards Heian and later periods, may still be of some use in looking up particular terms and getting to know the clothing and outfits.

At the farthest reaches of pre-history, we really don’t have a lot of information for clothing. There is evidence of woven goods in the Jomon period, and we have Yayoi burials with bits of cloth here and there, but these are all scraps. So at best we have some conjecture as to what people were wearing, and possibly some ability to look across the Korean peninsula and see what people had, there.

There are scant to no reliable records from early on in Japanese history, and most of those don’t really do a great job of describing the clothing. Even where we do get something, like the Weizhi, one has to wonder given how they tended to crib notes from other entries.

There is at least one picture scroll of interest: Portraits of Periodical Offering of Liang, or Liáng -Zhígòngtú. It is said to have been painted by Xiao Yi in the early 6th century, and while the original no longer exists there is an 11th century copy from the time of the Song Dynasty. The scroll shows various ambassadors to the Liang court, including one from Wa. The Wa ambassador is shown with what appears to be a wide piece of cloth around his hips and legs, tied in front. His lower legs are covered in what we might call kyahan today: a rather simple wrap around leg from below the knee to the foot. He has another, blue piece of cloth around his shoulders, almost like a shawl, and it is also tied in front. Then there is a cloth wrapped and tied around his head. It’s hard to know how much of this depiction is accurate and how much the artist was drawing on memory and descriptions from things like the Weizhi or Wei Chronicles, which stated that the Wa people wore wide cloths wrapped around and seamlessly tied

As such, it may be more helpful to look at depictions actually from the archipelago: specifically, some of the human-figured haniwa, those clay cylinders and statues that adorned the burial mounds which gave the kofun period its name. Some of these haniwa are fairly detailed, and we can see ties, collars, and similar features of clothing. These haniwa primarily seem to cluster towards the end of the Kofun period, in the later 6th century, so it is hard to say how much they can be used for earlier periods, though that is exactly what you will typically see for periods where we have little to know evidence. I’m also not sure how regional certain fashions might have been, and we could very much be suffering from survivorship bias—that is we only know what survived and assume that was everything, or even the majority. Still, it is something.

Much of what we see in these figures is some kind of upper garment that has relatively tight sleeves, like a modern shirt or jacket might have, with the front pieces overlapping create a V-shaped neckline. The garment hem often hangs down to just above the knee, flaring out away from the body, and it’s held closed with ties and some kind of belt, possibly leather in some cases, and in others it looks like a tied loop of cloth. There is evidence of a kind of trouser, with two legs, and we see ties around the knee. In some cases, they even have small bells hanging from the ties. Presumably the trousers might have ties up towards the waist, but we cannot see that in the examples we have. We also see individuals who have no evidence of any kind of bifurcated lower garment. That may indicate an underskirt of some kind, or possibly what’s called a “mo”—but it could also be just a simplification for stability, since a haniwa has a cylindrical base anyway. It is not always obvious when you are looking at a haniwa figure whether it depicts a man or woman: in some cases there are two dots on the chest that seem to make it obvious, but the haniwa do come from different artisans in different regions, so there is a lot of variability.

We also see evidence of what seem to be decorative sashes that are worn across the body, though not in all cases. There are various types of headgear and hairstyles. Wide-brimmed and domed hats are not uncommon, and we also see combs and elaborate hairstyles depicted. On some occasions we can even see that they had closed toed shoes. For accessories, we see haniwa wearing jewelry, including necklaces (worn by both men and women), bracelets, and earrings. In terms of actual human jewelry, early shell bracelets demonstrate trade routes, and the distinctive magatama, or comma shaped jewel, can be found in the archipelago and on the Korean peninsula, where it is known as “gogok”.

Based on lines or even colored pigment on the haniwa, it appears that many of these outfits were actually quite heavily decorated. Paint on the outfits is sometimes also placed on the face, suggesting that they either painted or tattooed themselves, something mentioned in the Wei Chronicles. We also have archaeological examples of dyed cloth, so it is interesting that people are often depicted in undyed clothing.

There is one haniwa that I find particularly interesting, because they appear to be wearing more of a round-necked garment, and they have a hat that is reminiscent of the phrygian cap: a conical cap with the top bent forward. These are traits common to some of the Sogdians and other Persian merchants along the silk road, raising the possibility that it is meant to depict a foreigner, though it is also possible that it was just another local style.

If we compare this to the continent, we can see some immediate difference. In the contemporaneous Sui dynasty, we can see long flowing robes, with large sleeves for men and women. The shoes often had an upturned placket that appears to have been useful to prevent one from tripping on long, flowing garments. Many of these outfits were also of the v-neck variety, with two overlapping pieces, though it is often shown held together with a fabric belt that is tied in front. The hats appear to either be a kind of loose piece of fabric, often described as a turban, wrapped around the head, the ends where it ties together trailing behind, or black lacquered crowns—though there were also some fairly elaborate pieces for the sovereign.

As Yamato started to import continental philosophy, governance, and religion, they would also start to pick up on continental fashion. This seems particularly true as they adopted the continental concept of “cap rank” or “kan-i". Let’s go over what we know about this system, from its first mention in the Chronicles up to where we are in Ohoama’s reign. As a caveat, there is a lot we don’t know about the details of these garments, but we can make some guesses.

The first twelve cap-ranks, theoretically established in 603, are somewhat questionable in their historicity, as are so many things related to Shotoku Taishi. And their names are clearly based on Confucian values: Virtue, Humanity, Propriety, Faith, Justice, and Wisdom, or Toku, Nin, Rei, Shin, Gi, and Chi. The five values and then just “Virtue”, itself. The existence of this system does seem to be confirmed by the Sui Shu, the Book of Sui, which includes a note in the section on the country of Wa that they used a 12 rank system based on the Confucian values, but those values were given in the traditional Confucian order vice the order given in the Nihon Shoki.

The rank system of the contemporaneous Sui and Tang dynasties was different from these 12 ranks, suggesting that the Yamato system either came from older dynasties—perhaps from works on the Han dynasty or the Northern and Southern Dynasty, periods—or they got it from their neighbors, Baekje, Silla, and Goguryeo. There does seem to be a common thread, though, that court rank was identifiable in one’s clothes.

As for the caps themselves, what did they look like? One would assume that the Yamato court just adopted a continental style cap, and yet, which one? It isn’t fully described, and there are a number of types of headwear that we see in the various continental courts. Given that, we aren’t entirely sure exactly what it looked like, but we do have a couple of sources that we can look at and use to make some assumptions.

These sources l ead us to the idea of a round, colored cap made of fabric, around the brim that was probably the fabric or image prescribed for that rank. It is also often depicted with a bulbous top, likely for the wearer’s hair, and may have been tied to their top knot.

Our main source for this is the Tenjukoku Mandala Embroidery (Tenjukoku-mandara-shuuchou) at Chuuguuji temple, which was a temple built for the mother of Prince Umayado, aka Shotoku Taishi.

This embroidery was created in 622, so 19 years after the 12 ranks would have been implemented. It depicts individuals in round-necked jackets that appear to have a part straight down the center. Beneath the jacket one can see a pleated hem, possibly something like a “hirami”, a wrapped skirt that is still found in some ceremonial imperial robes. It strikes me that this could also be the hem of something like the hanpi, which was kind of like a vest with a pleated lower edge. Below that we see trousers—hakama—with a red colored hem—at least on one figure that we can see. He also appears to be wearing a kind of slipper-like shoe.

As for the women, there are a few that appear to be in the mandala, but it is hard to say for certain as the embroidery has been damaged over the years. That said, from what we can tell, women probably would have worn something similar to the men in terms of the jacket and the pleated under-skirt, but then, instead of hakama, we see a pleated full-length skirt, or mo. We also don’t have a lot of evidence for them wearing hats or anything like that.

The round necked jacket is interesting as it appears to be similar to the hou that was common from northern China across the Silk Road, especially amongst foreigners. This garment came to displace the traditional robes of the Tang court and would become the basis for much of the court clothing from that period, onwards. The round necked garment had central panels that overlapped, and small ties or fastenings at either side of the neck to allow for an entirely enclosed neckline. This was more intricate than just two, straight collars, and so may have taken time to adopt, fully.

The next change to the cap-rank system was made in 647, two years into the Taika Reform. The ranks then were more directly named for the caps, or crowns—kanmuri—and their materials and colors. The ranks translate to Woven, Embroidered, Purple, Brocade, Blue, Black, and finally “Establish Valor” for the entry level rank.

The system gets updated two years later, but only slightly. We still see a reference to Woven stuff, Embroidery, and Purple, but then the next several ranks change to Flower, Mountain, and Tiger—or possibly Kingfisher. These were a little more removed from the cap color and material, and may have had something to do with designs that were meant to be embroidered on the cap or on the robes in some way, though that is just speculation based on later Ming and Qing court outfits.

Naka no Ohoye then updates it again in 664, but again only a little. He seems to add back in the “brocade” category, swapping out the “flower”, and otherwise just adds extra grades within each category to expand to 26 total rank grades.

And that brings us to the reforms of 685, mentioned last episode. This new system was built around what appear to be moral exhortations—Upright, Straight, Diligent, Earnest, etc. And that is great and all, but how does that match up with the official robes? What color goes with each rank category?

Fortunately, this time around, the Chronicle lays it out for us pretty clearly. First off we are given the color red for the Princely ranks—not purple as one might have thought. Specifically, it is “Vermillion Flower”, hanezu-iro, which Bentley translates as the color of the “Oriental bush” or salmon. In the blogpost we’ll link to a table of colors that the founder of Sengoku Daimyo, Anthony Bryant, had put together, with some explanation of how to apply it. I would note that there is often no way to know exactly what a given color was like or what shades were considered an acceptable range. Everything was hand-dyed, and leaving fabric in the dye a little longer, changing the proportions, or just fading over time could create slightly different variants in the hue, but we think we can get pretty close.

From there we have the six “common” ranks for the nobility. Starting with the first rank, Upright, we have “Dark Purple”. Then we have “Light Purple”. This pattern continues with Dark and Light Green and then Dark and Light Grape or Lilac. Purple in this case is Murasaki, and green here is specifically Midori, which is more specifically green than the larger category of “Aoi”, which covers a spectrum of blue to green. The grape or lilac is specifically “suou”, and based on Bentley’s colors it would be a kind of purple or violet.

The idea is that the official court outfits for each rank would be the proper color. And yes, that means if you get promoted in rank, your first paycheck—or rice stipend—is probably going to pay for a new set of official clothes. Fortunately for the existing court nobles at the time, in the last month of 685, the Queen provided court clothing for 55 Princes and Ministers, so they could all look the part.

And the look at court was important. In fact, several of the edicts from this time focus specifically on who was allowed—or expected—to wear what. For instance, in the 4th month of 681, they established 92 articles of the law code, and among those were various sumptuary laws—that is to say, laws as to what you could wear. We are told that they applied to everyone from Princes of the blood down to the common person, and it regulated the wearing of precious metals, pearls, and jewels; the type of fabric one could use, whether purple, brocade, embroidery, or fine silks; and it also regulated woollen carpets, caps, belts, and the colors of various things.

And here I’d like to pause and give some brief thought to how this played into the goals of the court, generally, which is to say the goal of creating and establishing this new system of governance in the cultural psyche of the people of the archipelago. From the continental style palaces, to the temples, and right down to the clothing that people were wearing, this was all orchestrated, consciously or otherwise, to emphasize and even normalize the changes that were being introduced. When everything around you is conforming to the new rules, it makes it quite easy for others to get on board.

The court had surrounded themselves with monumental architecture that was designed along continental models and could best be explained through continental reasoning. Even if they weren’t Confucian or Daoist, those lines of reasoning ran through the various cultural and material changes that they were taking up. Sure, they put their own stamp on it, but at the same time, when everything is right in front of you, it would become that much harder to deny or push back against it.

And when you participated in the important rituals of the state, the clothing itself became a part of the pageantry. It reinforced the notion that this was something new and different, and yet also emphasized that pushing against it would be going against the majority. So court uniforms were another arm of the state’s propaganda machine, all designed to reinforce the idea that the heavenly sovereign—the Tennou—was the right and just center of political life and deserving of their position.

Getting back to the sumptuary laws and rank based regulations: It is unfortunate that the record in the Nihon Shoki doesn’t tell us exactly how things were regulated, only that they were, at least in some cases. So for anything more we can only make assumptions based on later rules and traditions. A few things we can see right away, though. First is the restriction of the color purple. Much as in Europe and elsewhere in the world, getting a dark purple was something that was not as easy as one might think, and so it tended to be an expensive dye and thus it would be restricted to the upper classes—in this case the princely and ministerial rank, no doubt. Similarly brocade and fine silks were also expensive items that were likely restricted to people of a particular social station for that reason.

The mention of woolen rugs is particularly intriguing. Bentley translates this as woven mattresses, but I think that woolen rugs makes sense, as we do have examples of woolen “rugs” in Japan in at least the 8th century, stored in the famous Shousouin repository at Toudaiji temple, in Nara. These are all imported from the continent and are actually made of felt, rather than woven. As an imported item, out of a material that you could not get in the archipelago, due to a notable lack of sheep, they would have no doubt been expensive.

The funny thing is that the carpets in the Shousouin may not have been meant as carpets. For the most part they are of a similar size and rectangular shape, and one could see how they may have been used as sleeping mattresses or floor coverings. However, there is some conjecture that they came from the Silk Road and may have been originally meant as felt doors for the tents used by the nomadic steppe peoples. This is only conjecture, as I do not believe any of these rugs have survived in the lands where they would have been made, but given the size and shape and the modern yurt, it is not hard to see how that may have been the case. Either way, I tend to trust that this could very well have meant woolen rugs, as Aston and the kanji themselves suggest, though I would understand if there was confusion or if it meant something else as wool was not exactly common in the archipelago at that time or in the centuries following.

The last section of the regulations talks about the use of caps and belts. The caps here were probably of continental origin: The kanmuri, or official cap of state of the court nobles, or the more relaxed eboshi—though at this time, they were no doubt closely related.

In fact, a year later, we have the most specific mention to-date of what people were actually wearing on their heads: there is a mention of men tying up their hair and wearing caps of varnished gauze. Earlier caps related to the cap rank system are often thought to be something like a simple hemisphere that was placed upon the head, with a bulbous top where the wearer’s hair could be pulled up as in a bun.

The kanmuri seems to have evolved from the soft black headcloth that was worn on the continent, which would have tied around the head, leaving two ends hanging down behind. Hairstyles of the time often meant that men had a small bun or similar gathering of hair towards the back of their head, and tying a cloth around the head gave the effect of a small bump. This is probably what we see in depictions of the early caps of state. Sometimes this topknot could be covered with a small crown or other decoration, or wrapped with a cloth, often referred to as a “Tokin” in Japanese. But over time we see the development of hardened forms to be worn under a hat to provide the appropriate silhouette, whether or not you actually had a topknot (possibly helpful for gentlemen suffering from hair loss). And then the hat becomes less of a piece of cloth and more just a hat of black, lacquered gauze made on a form, which was much easier to wear.

At this point in the Chronicle, the cap was likely still somewhat malleable, and would made to tie or be pinned to that bun or queue of hair. This explains the mention of men wearing their hair up. This pin would become important for several different types of headgear, but ties were also used for those who did not have hair to hold the hat on properly.

Two years after the edict on hats, we get another edict on clothing, further suggesting that the court were wearing Tang inspired clothing. In 685 we see that individuals are given leave to wear their outer robe either open or tied closed. This is a clue that this outer robe might something akin to the round-necked hou that we see in the Tenjukoku Mandala, where the neck seems to close with a small tie or button. However, we do see some examples, later, of v-necked garments with a tie in the center of the neck, so that may be the reference.. Opening the collar of the formal robes was somewhat akin to loosening a necktie, or unbuttoning the top button of a shirt. It provided a more relaxed and comfortable feeling. It could also be a boon in the warm days of summer. Leaving it closed could create a more formal appearance.

The courtiers also had the option of whether or not to wear the “Susotsuki”, which Bentley translates as “skirt-band”. I believe this refers to the nai’i, or inner garment. This would often have a pleated hem—a suso or ran—which would show below the main robe as just a slight hem. Again, this is something that many would dispense with in the summer, or just when dressing a bit more casually, but it was required at court, as well as making sure that the tassles were tied so that they hung down.

This was the uniform of the court. We are also told that they would have trousers that could be tied up, which sounds like later sashinuki, though it may have referred to something slightly different. We are also given some regulations specifically for women, such as the fact that women over 40 years of age were allowed the discretion on whether or not to tie up their hair, as well as whether they would ride horses astride or side-saddle. Presumably, younger women did not get a choice in the matter. Female shrine attendants and functionaries were likewise given some leeway with their hairstyles.

A year later, in 686, they do seem to have relaxed the hairstyles a bit more: women were allowed to let their hair down to their backs as they had before, so it seems that, for at least a couple of years, women under the age of 40 were expected to wear their hair tied up in one fashion or another.

In that same edict, men were then allowed to wear “habakimo”. Aston translates this as “leggings” while Bentley suggests it is a “waist skirt”. There are an example of extant habakimo in the Shousouin, once again, and they appear to be wrappings for the lower leg. It actually seems very closely related to the “kyahan” depicted all the way back in the 6th century painting of the Wo ambassador to Liang.

Even though these edicts give a lot more references to clothing, there is still plenty that is missing. It isn’t like the Chroniclers were giving a red carpet style stitch-by-stitch critique of what was being worn at court. Fortunately, there is a rather remarkable archaeological discovery from about this time.

Takamatsuzuka is a kofun, or ancient burial mound, found in Asuka and dated to the late 7th or early 8th century. Compared to the keyhole shaped tombs of previous centuries, this tomb is quite simple: a two-tiered circular tomb nestled in the quiet hills. What makes it remarkable is that the inside of the stone burial chamber was elaborately painted. There are depictions of the four guardian animals, as well as the sun and the moon, as well as common constellations. More importantly, though, are the intricate pictures of men and women dressed in elaborate clothing.

The burial chamber of Takamatsuzuka is rectangular in shape. There are images on the four vertical sides as well as on the ceiling. The chamber is oriented north-south, with genbu, the black tortoise, on the north wall and presumably Suzaku, the vermillion bird, on the south wall—though that had been broken at some point and it is hard to make out exactly what is there.

The east and west walls are about three times as long as the north and south walls. In the center of each is a guardian animal—byakko, the white tiger, on the west wall and seiryuu, the blue—or green—dragon on the east. All of these images are faded, and since opening of the tomb have faded even more, so while photos can help, it may require a bit more investigation and some extrapolation to understand all of what we are looking at.

On the northern side of both the east and west wall we see groups of four women. We can make out green, yellow, and red or vermillion outer robes with thin fabric belt sashes, or obi, tied loosely and low around the waist. There is another, lightly colored—possibly white, cream or pink—that is so faded it is hard to make out, and I don’t know if that is the original color. These are v-necked robes, with what appear to be ties at the bottom of the “v”. Around the belt-sash we see a strip of white peaking out from between the two sides of the robe—most likely showing the lining on an edge that has turned back slightly. The cuffs of the robe are folded back, showing a contrasting color—either the sleeves of an underrobe or a lining of some kind. Below the outer robe is a white, pleated hem—possibly a hirami or similar, though where we can make it out, it seems to be the same or similar color as the sleeves. Under all of that, they then have a relatively simple mo, or pleated skirt. The ones in the foreground are vertically striped in alternating white, green, red, and blue stripes. There is one that may just be red and blue stripes, but I’m not sure. In the background we see a dark blue—and possibly a dark green—mo. At the base of each mo is a pleated fringe that appears to be connected to the bottom of the skirt. The toe of a shoe seems to peek out from underneath in at least one instance. They don’t have any obvious hair ornaments, and their hair appears to be swept back and tied in such a way that it actually comes back up in the back, slightly. They appear to be holding fans and something that might be a fly swatter—a pole with what looks like tassels on the end.

In comparison, at the southern end of the tomb we have two groups of men. These are much more damaged and harder to make out clearly. They have robes of green, yellow, grey, blue, and what looks like dark blue, purple, or even black. The neckline appears to be a v-necked, but tied closed, similar to what we see on the women. We also see a contrasting color at the cuff, where it looks like the sleeves have turned back, slightly. They have belt-sashes similar to the women, made of contrasting fabric to the robe itself. Below that we see white trousers, or hakama, and shallow, black shoes. On some of the others it is suggested that maybe they have a kind of woven sandal, but that is hard to make out in the current image. On their heads are hats or headgear of black, stiffened—probably lacquered—gauze. They have a bump in the back, which is probably the wearer’s hair, and there is evidence of small ties on top and larger ties in the back, hanging down. Some interpretations also show a couple with chin straps, as well, or at least a black cord that goes down to the chin. They carry a variety of implements, suggesting they are attendants, with an umbrella, a folding chair, a pouch worn around the neck, a pole or cane of some kind, and a bag with some kind of long thing—possibly a sword or similar.

The tomb was originally found by farmers in 1962, but wasn’t fully examined until 1970, with an excavation starting in 1972. The stone at the entryway was broken, probably from graverobbers, who are thought to have looted the tomb in the Kamakura period. Fortunately, along with the bones of the deceased and a few scattered grave goods that the robbers must have missed, the murals also survived, and somehow they remained largely intact through the centuries. They have not been entirely safe, and many of the images are damaged or faded, but you can still make out a remarkable amount of detail, which is extremely helpful in determining what clothing might have looked like at this time—assuming it is depicting local individuals.

And there is the rub, since we don’t know exactly whom the tomb was for. Furthermore, in style it has been compared with Goguryeo tombs from the peninsula, much as nearby Kitora kofun is. Kitora had images as well, but just of the guardian animals and the constellations, not of human figures.

There are three theories as to who might have been buried at Takamatsuzuka. One theory is that it was one of Ohoama’s sons. Prince Osakabe is one theory, based on the time of his death and his age. Others have suggested Prince Takechi. Based on the teeth of the deceased, they were probably in their 40s to 60s when they passed away.

Some scholars believe that it may be a later, Nara period vassal—possibly, Isonokami no Maro. That would certainly place it later than the Asuka period.

The third theory is that it is the tomb of a member of one of the royal families from the Korean peninsula—possibly someone who had taken up refuge in the archipelago as Silla came to dominate the entire peninsula. This last theory matches with the fact that Takamatsuzuka appears to be similar to tombs found in Goguryeo, though that could just have to do with where the tomb builders were coming from, or what they had learned.

That does bring up the question of the figures in the tomb. Were they contemporary figures, indicating people and dress of the court at the time, or were they meant to depict people from the continent? Without any other examples, we may never know, but even if was indicative of continental styles, those were the very styles that Yamato was importing, so it may not matter, in the long run.

One other garment that isn’t mentioned here is the hire, a scarf that is typically associated with women. It is unclear if it has any relationship to the sashes we see in the Kofun period, though there is at least one mention of a woman with a hire during one of the campaigns on the Korean peninsula. Later we see it depicted as a fairly gauzy piece of silk, that is worn somewhat like a shawl. It is ubiquitous in Sui and Tang paintings of women, indicating a wide-ranging fashion trend. The hire is a fairly simple piece of clothing, and yet it creates a very distinctive look which we certainly see, later.

Finally, I want to take a moment to acknowledge that almost everything we have discussed here has to do with the elites of society—the nobles of the court. For most people, working the land, we can assume that they were probably not immediately adopting the latest continental fashions, and they probably weren’t dressing in silk very much. Instead, it is likely that they continued to wear some version of the same outfits we see in the haniwa figures of the kofun period. This goes along with the fact that even as the elite are moving into palaces built to stand well above the ground, we still have evidence of common people building and living in pit dwellings, as they had been for centuries. This would eventually change, but overall they stuck around for quite some time. However, farmers and common people are often ignored by various sources—they aren’t often written about, they often aren’t shown in paintings or statues, and they did often not get specialized burials. Nonetheless, they were the most populous group in the archipelago, supporting all of the rest.

And with that, I think we will stop for now. Still plenty more to cover this reign. We are definitely into the more historical period, where we have more faith in the dates—though we should remember that this is also one of the reigns that our sources were specifically designed to prop up, so we can’t necessarily take everything without at least a hint of salt and speculation, even if the dates themselves are more likely to be accurate.

Until then, if you like what we are doing, please tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

Thank you, also, to Ellen for their work editing the podcast.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Bentley, John R. (2025). Nihon Shoki: The Chronicles of Japan. ISBN 979-8-218634-67-4 pb

Izutsu, Yohei; et al (Last Reviewed 2025). The Kyoto Costume Museum Website. https://www.iz2.or.jp.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4.