Previous Episodes

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we start to look at Shōtoku Taishi, the Crown Prince of Great Virtue. He is a legendary figure, and his story is probably an amalgamation of several stories put together. That said, determining the story of the real prince, vice the legend, is a task that can cause any scholar pause. Here we’ll mainly look at the narrative surrounding him and try to get a sense of these stories.

Timeline of Shōtoku Taishi’s Life

574 - Born

593 - Umayado was made Crown Prince [Taishi]

593 - Umayado's father, Tachibana no Toyohi, was removed and re-interred in the tomb of Shinaga, in Kawachi

593 - Building of Shitennouji started

594 - Kashikiya Hime instructed Umayado and Umako to promote Buddhism

595 - Hye-cha (Eiji) arrives from Goguryeo and becomes Umayado's teacher

596 - Hōkōji is "finished"

601 - Umayado begins construction of the Ikaruga Palace

603, 2/4 - Kashikiya Hime consults with Umako and Umayado on what to do after the death of Prince Kume, who was going to lead an expedition to "free" Nimna

603, 11/1 - Umayado has a Buddhsit image and offers it to Hata no Miyatsuko no Kawakatsu to worship. Kawakatsu founds Kōryūji in Yamashiro

603, 11th month - Umayado gets permission to commission shields, quivers, and banners as temple offerings

604 - Umayado establishes the cap ranks and the 17 Article Constitution

605, 4/1 - Kashikiya Hime had Umayado, Umako, and all of the the ministers take a vow and then commissioned an embroidered and a copper (bronze?) image of the Buddha [which was placed in Asukadera]

605, 7/1 - Umayado commands all of the ministers to wear the "Hirahi" outer garment

605, 10th month - Umayado took up residence at Ikaruga

606, 7th month - Kashikiya Hime asked Umayado to lecture on the "Shōman" sutra, which he did over 3 days. Later in that same year he lectured on the Lotus Sutra, and received 100 cho of rice paddies to support a temple on his property at Ikaruga—aka Hōryūji

607, 2/15 - Umayado and all of the ministers were ordered to worship the kami of Heaven and Earth

613 - Umayado writes the Gangōji Garan Engi

613 - Umayado journeys to Katawoka and encounters a starving man

620 - Umayado writes the "Kūjiki" (supposedly)

621 - Umayado dies, he is buried in the Shinaga Misasagi (with his father)

624 - Inabe Tachibana no Iratsume commissioned a member of the Hata to make a tapestry (Tenjūkoku Mandala) in honor of her husband

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is Episode 98: The Legend of Shotoku Taishi.

If you’ve been following along with this podcast, the name Shotoku Taishi should be familiar, as we’ve referenced him several times over the course of the past episodes. He’s more broadly famous as a semi-legendary figure in Japanese history—while the current period, that is the end of the 6th and early 7th centuries, is fairly well documented with clear, historic events, , the position of Crown Prince Shotoku is often questioned, and with good reason. The legends and history surrounding him are blended in such a way that it is often to tell what is actually reliable history, vice merely legend. Indeed, last episode we covered how Michael Como and others have talked about the “Cult” of Shotoku Taishi in Japanese Buddhism,. By this, we are referring to the beliefs surrounding Shotoku Taishi, including the legends, but also, eventually various rituals where he, himself, was seen as a Boddhisatva or Buddha figure—Japan’s first Buddhist saint. The beliefs surrounding him continued to be propagated through various temple records and miraculous stories and histories, which became only more numerous with time. We also find slightly different traditions that spring up around different temples and with the involvement of different families of different ethnic descent.

Honestly, I should probably have saved this for two more episodes, when we hit episode 100,—someone like Shotoku Taishi probably deserves a special place in any historical survey. Even if the majority of the information about him is legendary, there is no denying the imprint that this legend had on the course of Japanese history. At the same time, I don’t want to follow in the footsteps of others who deliberately over-emphasized the Prince’s role. So I’ll try to thread that needle here, because I don’t think we can get away without addressing something, and we will no doubt revisit this information more than a few times in the coming centuries, if not later.

So, my approach is that we’ll first take a look at the legends, and then, next episode, at the man behind them—such as we might be able to discern. The problems with the kind of hagiographic material surrounding someone like Shotoku Taishi is that it can become extremely hard to dig into the actual truth of the matter. After all, hagiographies are, by definition, about the lives of saints, and as such prone to exaggeration due to the stories told by True Believers.For Americans, one might think back to stories of our own first President, George Washington. Think about all of the things people “know” about him: from his wooden teeth and chopping down a cherry tree, to his reputation as a great general who won many battles. Many of those things are false or at least exaggerated, much as the painting of him crossing the Delaware makes for a much more majestic and patriotic image than was likely the case when it actually happened. And this is a famous person from less than three centuries ago, where we have copious independent records for historians to comb through to find the truth. But these legends persist, and often we find them comforting, heart-warming, or they simply add to the excitement. The idea that people are just, well, people doesn’t garner nearly as much interest.

These legends serve a purpose, though. They aren’t merely comforting, but they actually help us to tell stories about ourselves—about who we are and who we want to be. These stories often worm their way into society, and are passed down to our children. Through these stories we help create a common image that defines a common cultural identity. Different people who have never met can still see themselves as part of this culture through these cultural imaginaries. This is one of the reasons that these stories, at this point in history, are so fascinating, because the common image of what it meant to be a person of Wa, or even Yamato, was changing. Foreign ideas and concepts were coming in, and figures like Shotoku Taishi became the perfect vehicle to help tell the stories that would help localize a lot of those concepts.

At the same timethis kind of legendary treatment also feeds in to what has been called the “great man” approach to history, which focuses on the impact that single individuals had on historical trends. While this absolutely happens, many of the trends and great movements are rarely the result of a single person and their force of will—despite what anime might teach you. Certainly there are people who are present at turning points in history, and have the ability to help shape the direction that change might take, but often they themselves are products of a complex web of cultural and societal influence and change. They often make the story much easier to tell, resulting in what Terry Pratchett referred to as “lies to children”. Realistically, the change that was happening, and even the imagining of a new cultural identity, didn’t occur all at once, by a single individual. Instead, there were multiple stories, multiple narratives, and multiple imaginings that were going on, all at the same time. Whether consciously or not, these different stories demonstrate different ways of conceptualizing the common culture. Then, with the compilation of things like the Nihon Shoki, the Chroniclers chose those stories that fit the narrative they wanted to tell about the nation and about the royal line. Still, they often pulled stories from different traditions, which is why they don’t always line up exactly, but which also helps us to see some of the competing views of identity in the ancient past.

The mythmaking and imagining didn’t stop there, however. Thesehero stories, when treated as historical fact, can also be used in more sinister ways, and they’ve been actively employed and even updated throughout history, for a variety of purposes. We’ve talked about how nationalist narratives leaned hard on the legends of “Empress Jingu” to support Japan’s involvement with and eventual invasion of the Korean peninsula in the early 20th century. As for Shotoku Taishi, he has often been one of the figures held up as the father of the Japanese nation, and an important legend in the myths supporting the special character and longevity of the imperial line.

In modern scholarship, a line is often drawn between the historical prince—whoever that might have actually been—and this mythical person that the stories turned him into—the Shotoku Taishi. Most of the works exhorting the myth refer to him by this name, whereas those attempting to look at the historical man often use one of his other names—either Prince Umayado, the Prince of the Stable Door, or Prince Kamitsumiya, the Prince of the Upper Palace. I’ve been generally trying to keep to this, using Umayado for the historical personage and Shotoku Taishi for the myth, though it can be hard to determine just what is what.

Modern attempts to use the legend of Shotoku Taishi to prop up the state and the royal line are nothing new. The stories of Shotoku Taishi have lived on in Japanese history since the first Chronicles. A great example of this comes from the 14th century Jinnou Shoutouki, Kitabatake Chikafusa’s attempt to provide an historical overview of the Imperial line—and thus prove Japan’s unique position in the world. They say the first draft was written from memory, with only an outline of the imperial lineage to assist him, though no doubt later he was able to reference some materials. His outline, while perhaps not entirely accurate—we’ve already noted in previous episodes where his dates and facts didn’t align with the 8th century histories—is almost that much better for demonstrating the kind of beliefs that were held about these legends.

According to the histories, Shotoku Taishi was the son of Tachibana no Toyohi and Anahobe no Hashihito. Anahobe, who would eventually be known as the sovereign Youmei Tennou, was, himself the son of Ame Kunioshi Hiraki Hiro Niwa, aka Kimmei Tennou, and Kitashi Hime, daughter of Soga no Iname. That means his father was brother to Kashikiya Hime, making Shotoku Taishi her nephew, while Soga no Umako was his grand uncle.

Of his birth in about 573 it is said, and here I’ll use Paul Varley’s translation of the Jinnou Shoutouki, with a few liberties for clarity:

“Many wonderous omens accompanied this prince’s birth as signs that he was no ordinary person. At the time he was born, Prince Umayado’s hands were clasped together; and at age two he turned toward the east and, while intoning the name of the Buddha, opened his hands to reveal a relic of the Buddha. Without a doubt, this prince was the avatar of a deity who came to earth in order to spread Buddhist Law. The relic is now worshipped at Houryuuji in Yamato.”

Later, in the reign of Kimmei: “Oho-muraji Yuge no Moriya opposed the emperor’s efforts [to disseminate Buddhism] and finally turned to rebellion. Prince Umayado and Oho-omi Soga no Umako joined together and killed Moriya, thus making possible the spread of the Buddhist Law.”

During Sushun’s reign, “Emperor Sushun revealed signs in his physiognomy that he would suffer an unnatural death and was duly cautioned by Prince Umayado.” As you may recall, he was assassinated at the behest of Soga no Umako.

Finally, during the reign of Suiko: “Prince Umayado was made crown prince and, with the additional title of regent, was also entrusted with administration of the many affairs of court government. Although crown princes in the past governed in the absence of sovereigns from the capital, such periods of governance were temporary. Prince Umayado, on the other hand, truly ruled the country.

“Because Crown Prince Umayado possessed great virtue (shoutoku), the people revered him as they would an emperor, who is like the sun, and looked up to his virtue as they would to the clouds on high. Before he became crown prince, Umayado had destroyed the rebel minister Moriya, thus opening the way to the dissemination of the Buddhist Law in our country. After he assumed administration of the government at court, the three treasures were revered and the True Law of Buddhism (shoubou) was propagated with the same vigor as during Shakya’s own time.

“Prince Umayado had superhuman faculties, and when he donned priestly robes and expounded on the sutras, flowers showered down from heaven, light shone forth from his forehead, and the earth trembled. Since these were all signs similar to those manifested when the Buddha preached the Lotus Sutra, the empress and the ministers at court worshipped Umayado as though he were a Buddha.

“Prince Umayado built temples in more than forty places. And in a country where the people had from ancient times been of a simple nature and had lived entirely without rules, he instituted a cap-ranking system… [and] he compiled and presented to the throne a constitution of seventeen articles. In compiling the constitution, Prince Umayado delved deeply into the profound ways of both the inner (Buddhist) and outer (Confucian and Taoist) texts and presented their essences. Overjoyed, the empress issued the constitution to the country.

“In 621, Prince Umayado died at the age of forty-nine. The empress and the people of the country were overwhelmed with grief and mourned for him as they would for a parent. Umayado had been expected to succeed to the throne, but—since he was an avatar of the Buddha—there was no doubt some profound reason why he died before the empress. He was given the posthumous name of Shoutoku.”

This does a pretty good job of laying out the myth of Shotoku Taishi—with “Shotoku” meaning “Great Virtue” and “Taishi” meaning “Crown Prince”. At the same time, it is clearly mythical in nature. After all, he was supposedly born with relics of the Buddha in his clasped hands, which he didn’t unclasp until he was two years old. And then everything big that happens, he seems to be at the center of. He is credited with the defeat of Mononobe no Moriya, despite his young age, he is said to have built forty temples, and he instituted the rank system and founded the country with the first constitution. They do everything except name him an emperor—Tennou—in his own right. Heck, he’s even an incarnation of the Buddha. He was a triple threat: a Buddha, a Sage, and the Sovereign.

From here, we are mostly going to look at the stories from the Nihon Shoki or from other 8th century sources, but as I said, these are chock-ful of later additions. Still, it can be helpful to understand that the Nihon Shoki is just as infected with this mythical narrative. In fact, much of what Chikafusa was pulling from is accurate, at least according to the Chronicles. There they say that Shotoku Taishi could speak as soon as he was born, and as an adult he could listen to ten different legal cases at the same time and decide all of them without making any mistakes. He studied the Buddhist and Confucian classics and became proficient in them.

We don’t know exactly when Shotoku Taishi was born, but Chikafusa put it around a date that would equate, for us, to about 574. Beyond being born with a relic between his hands, we aren’t given a lot about his early life in the Nihon Shoki, but that didn’t stop later authors from filling in some of the gaps. One example is the story about the priest, Nichira, recognizing the precocious Buddha nature of the young Shotoku Taishi when the latter was only eight years old—so maybe in the early 580s. We talked about Nichira back in episode 89. He was said to be from Yamato, though his name almost seems like he’s from the Korean peninsula, and he was deeply involved in some of the cross-strait politicking of the time. At the same time, he had what I can only describe as “superpowers”, if we are to believe the accounts. He was apparently able to radiate light, and that light shone back from Shotoku Taishi, indicating his Buddha nature.

Of course, that story comes to us through the 12th century Konjaku Monogatari, so who knows when, exactly, it originated, though Nichira himself is present in the Nihon Shoki.

Speaking of which, we also have a story from 587, during the Soga-Mononobe War, which we covered in Episode 91. As a young man, Prince Shotoku Taishi went to battle with Soga no Umako, and he is said to have prayed to the four heavenly kings, the Shitenno, from the Golden Light Sutra, and they had helped the pro-Buddhist—which is to say the Soga—forces defeat the Mononobe and their allies.

As an adult, he was made Crown Prince in 593, and he was given quarters in the Eastern Palace, the traditional quarters of the heir apparent. From there we are told that he “discharged the duties of sovereign, being associated with Kashikiya Hime in the management of all matters of administration.” This might actually be true, to some extent, but taken together with everything else it fits in with the fantastical legends. It certainly bolsters the claim that he was as much a secular authority as he was a religious one, which would later prop up ideas that he was a sage king or that he was a “wheel turning sovereign”, to use the Buddhist terminology.

Speaking of his palace—Shotoku Taishi is often referred to by one of the early palaces where he resided, Kamitsumiya, the Upper Palace. In fact, he is often just called Prince Kamitsumiya, and even his Heian era biography uses the term “Jouguu”, another reading of “Upper Palace”, and is thus known in abbreviated form as the Jouguuki. However, he eventually wanted to have something of his own, and in 601 he began work on a Palace in the area of Ikaruga.

The choice of Ikaruga is interesting. Kashikiya Hime is said to have lived in the Toyoura Palace, and later the Woharida Palace, both thought to be near the house of Soga no Umako in the area of modern Asuka, along the Asuka river. Ikaruga, however, is about a four and a half hour walk to the north, on the other side of the Nara basin. That would have certainly been doable, but it puts quite the distance between Shotoku Taishi and the nominal seat of power, especially if he is assisting Kashikiya Hime’s rule.

It would, however, have put him close to his mother, Anahobe no Hashihito, as she apparently had a palace out near there, and that may have been the reason for his own palace to have been located up there.

Of course, Shotoku Taishi is credited with basically anything that happens in this period, regardless of if he is clearly mentioned in the Nihon Shoki or not, so we have to wonder about a lot of that. He is said to have instituted the cap-rank system, he developed the 17 article constitution, and he initiated contact with the Sui dynasty—see episodes 95 and 96.

He is attributed with really kicking off a temple building boom in the Asuka period. These include Shitennouji, Houryuuji, Houkouji—aka Asukadera—, and Kouryuuji. Later he is said to have also inspired the building of Daianji, the largest Buddhist temple in the archipelago at its completion.

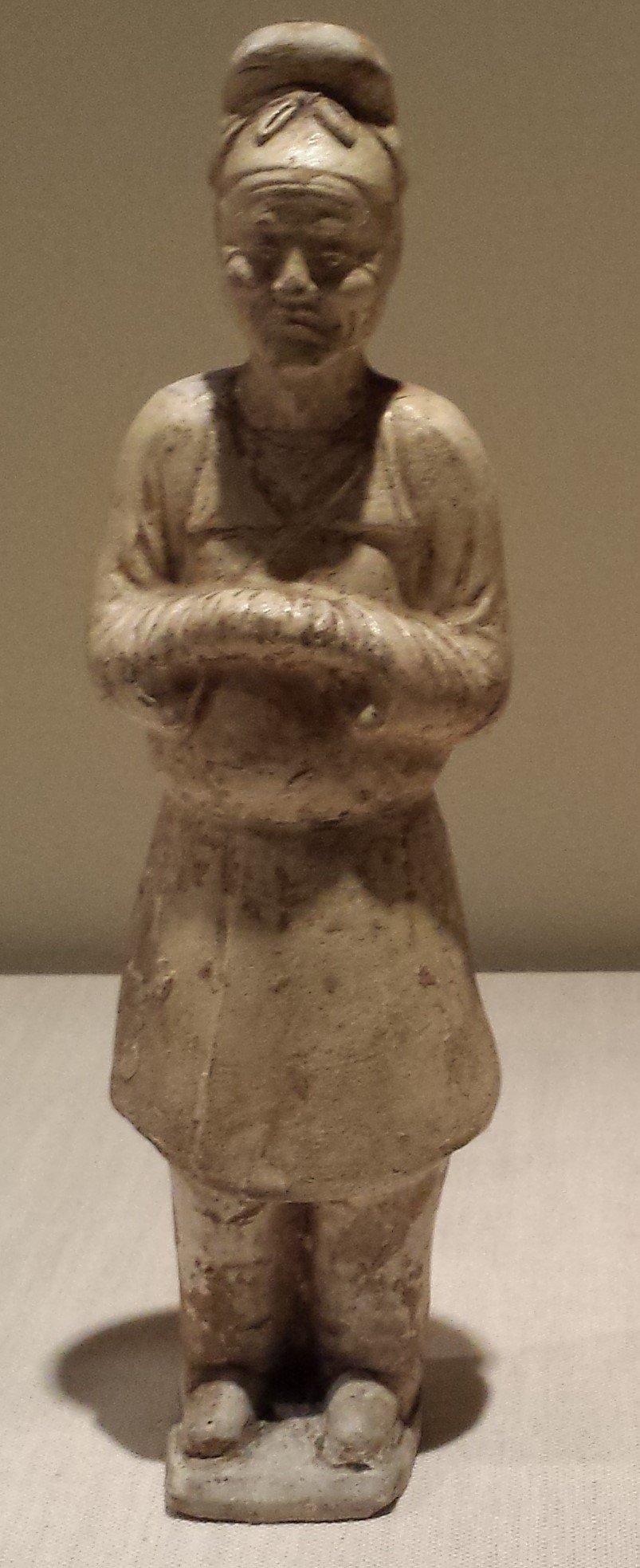

We talked a bit about Asukadera and Shitennouji last episode, and how Shotoku Taishi and Soga no Umako were exhorted to spread Buddhism around the archipelago. Both are attributed to Shotoku Taishi in some way—though Asukadera has much stronger ties to Soga no Umako, based on the evidence. We haven’t yet mentioned Kouryuuji, but it is also important. It is said that Shotoku Taishi acquired a statue of Miroku, aka Maitreya, the future Buddha, and he started asking amongst the noble houses of Yamato if there was anyone who wanted to build a temple to it. He was taken up on his offer by Hata no Kawakatsu, who built the temple of Kouryuuji in his home territory.

As we discussed before, back in episode 63, the Hata family had a base of operations around modern Kyoto, and the temple of Kouryuuji is still there, in the Uzumasa district, aka the district of the Great Hata. This is an easy trip out of Kyoto, out towards Arashiyama, and well worth a visit. The buildings have burned down and been rebuilt numerous times, but it preserves two Miroku statues from the Asuka period. One of them in particular, known as the houkan miroku, is thought to have been imported from the Korean peninsula, and both are considered national treasures, along with many others. In fact, if you’ve seen any works on Japanese Buddhist images, you’ve probably seen this particular one, in a thoughtful pose, with one leg up, elbow on his knee, hand up to his chin. The Hata were a powerful family in that region, and we’ll see more of them, later in the story, but here we can see that they’ve made a clear connection to Shotoku Taishi, the saintly founder of the nation.

That said, as far as connections to Shotoku Taishi go, all of these other temples are beat out by Houryuuji. We are told that Houryuuji was founded in 606, when Shotoku Taishi gave a lecture on the Lotus Sutra, one of the most influential sutras in Mahayana Buddhism. It is said that he did so well he was rewarded with 100 cho of rice paddies to support a temple at his property in Ikaruga. That temple is Houryuuji temple.

Houryuuji is incredible, and if you ever get a chance to see it you absolutely should. As I noted last episode, it has the oldest extant wooden building in the world, and it is a treasure trove of art history from this era, even though it suffered its own fires and other problems. While many of the buildings have been reconstructed, it still has the main image hall, or kondou, dating back about 1300 years, probably last built around 711 CE.

You don’t have to go to Houryuuji to see all of the treasures, however—many are on display in a special permanent exhibition in the Japanese National Museum in modern Tokyo. However, there’s nothing quite like the feeling you get walking around the temple grounds, which were relocated early on a bit to the northwest of the original location.

This temple includes several ancient Buddha images, including one that, quite notably, is said to have been built based on the proportions of Shotoku Taishi himself. We know this because they tell us in an inscription on the back of the image. That inscription refers to Shotoku Taishi as a prince and also as a Dharma ruler.

The exact style of Buddhism practiced at the temple has differed over the years. For a time it was Sanron shu, but for a long time it was part of the Hossou Sect until, in the 1950s, it broke away as the head of a sect known as the Shotoku sect, or Shotoku-shu, which is its modern affiliation.

As noted, this temple is said to have been built on land from Shotoku Taishi’s own Ikaruga Palace, and one might think that it was always the center of the beliefs and worship surrounding Shotoku Taishi himself. And that may have been the case if tragedy hadn’t struck in 670, when lightning struck and all of the buildings burnt down. I’m sure we’ll cover that when we get to it, but one of the apparent results was that Houryuuji was in a rebuilding phase for what seems to be some 30 to 40 years, and that was likely the time that many of the stories about Shotoku Taishi that would be included in the Chronicles were being solidified, and so we don’t have as much in the Nihon Shoki as one might otherwise imagine.

As we mentioned, Shotoku Taishi was not just some prince spending money on temple projects, and as part of building on his Buddhist bona fides, we are also told that he was quite learned. In 595, the Buddhist Priest Hye-cha, or Eiji, in Japanese, came over from Goguryeo and we are told that he became Shotoku Taishi’s teacher. Of course, Shotoku Taishi is already said to have known quite a bit—he was born with Buddhist relics, his Buddha nature was obvious to Nichira, and he knew enough to be able to pray to the Four Heavenly Kings for victory, not to mention all the temples he started. Nonetheless, it was under Eiji where he seems to have undertaken his most serious study of Buddhism, and their connection is emphasized in stories both from the Nihon Shoki and from other material. For instance, they are mentioned together in surviving sections of the Iyo Fudoki, submitted in 715, where they are said to have traveled to the land of Iyo, on the island of Shikoku, reacting to it kind of like a pair of ancient tourist buddies. Although Eiji was his teacher, in many ways they are portrayed as equals.

Shotoku Taishi learned a great deal, and the Nihon Shoki notes at least two instances where he gave lectures on the sutras. One of those was a 606 lecture on the Lotus Sutra, whereby he raised the funds for Houryuuji, but earlier in that same year he is said to have given a lecture regarding the Shouman, or Srimaladevi, sutra. He gave it at the behest of Kashikiya Hime, and we are told that he was able to expound upon it over the course of three days.

These lectures are not all. There are three surviving sutra commentaries that are all attributed to Shotoku Taishi. One is on the Shouman sutra, while another is on the Lotus Sutra. The third is on the Yuima, or Vimalakirti, Sutra. These are thought to have been completed in 611, 615, and 613, respectively. Of them, only the Lotus sutra commentary remains in manuscript form, while the others exist only from later copies. Together they are known as the Sangyou Gisho. The actual authorship is not entirely certain, but they have been associated with Shotoku Taishi since at least 747, and there are corroborating accounts in some of the Shousouin documents of Toudaiji, in Nara, as well.

In addition to those commentaries, Shotoku Taishi, who apparently had copious amounts of time, is also said to have written the first historical account of the era. In fact, the Sendai Kuji Hongi—or just the Kuujiki—is said to have been written by him, and the Kojiki is related to his work as well. This is why both the Kuujiki and the Kojiki end with the reign of Kashikiya Hime, aka Suiko Tennou, since Shotoku would not have been able to write about anything after his death.

While the Kojiki stopped providing juicy historical details far earlier than Shotoku’s time, it continued to provide lineage information up until this reign—until the time of Shotoku Taishi. In the case of the Kuujiki, however, we have some other problems with the hypothesis that he wrote it. Namely, the issue that the Sendai Kuji Hongi seems extremely obsessed with the lineages of the Mononobe and Owari clans, which seems a rather odd flex if it had been written by Shotoku Taishi, who had helped overthrow the Mononobe, ostensibly because they were Anti-Buddhist.

There are some who suggest that all of these Chronicles, including the Nihon Shoki, may have included older works that are no longer extant, including the text said to have been penned—or at least commissioned—by Shotoku Taishi, or at least during his era. To be more specific, the Nihon Shoki itself claims that he drew up a history of the sovereigns, a history of the country, as well as the original record of the Omi, the Muraji, the Tomo no Miyatsuko, the Kuni no Miyatsuko, the 180 Be, and other Free subjects who did not fit into one of the other categories.

Curiously this was in the year 620—the 28th year of Kashikiya Hime’s reign. That’s exactly 100 years prior to the completion of the Nihon Shoki, in 720: a curious date, but perhaps simply coincidence, since the entry immediately following this is the talk of Shotoku Taishi’s death in the following year: 621, on the 5th day of the 2nd month. This conveniently means that he would have recorded everything up to his death… and presumably any information after that was tacked on at a later point.

As for how he died, we are told that Prince Shotoku died in his sleep in the middle of the night in the palace in Ikaruga. The Nihon Shoki describes how the entire nation mourned for him. The Princes and the Omi, as well as all of the other people of the realm all mourned. The elderly felt as though they had lost a child, whilst the young felt as if they had lost a parent. The taste of food turned to ash in their mouths, and the roads were filled with the sound of wailing. Farmers stopped working, and women stopped pounding the mortar and pestle.

They all said: “The Sun and Moon have lost their brightness; heaven and earth have crumbled to ruin: henceforward, in whom shall we put our trust?”

This goes to the idea that the Prince was recognized in his own time as a particularly saintly figure.

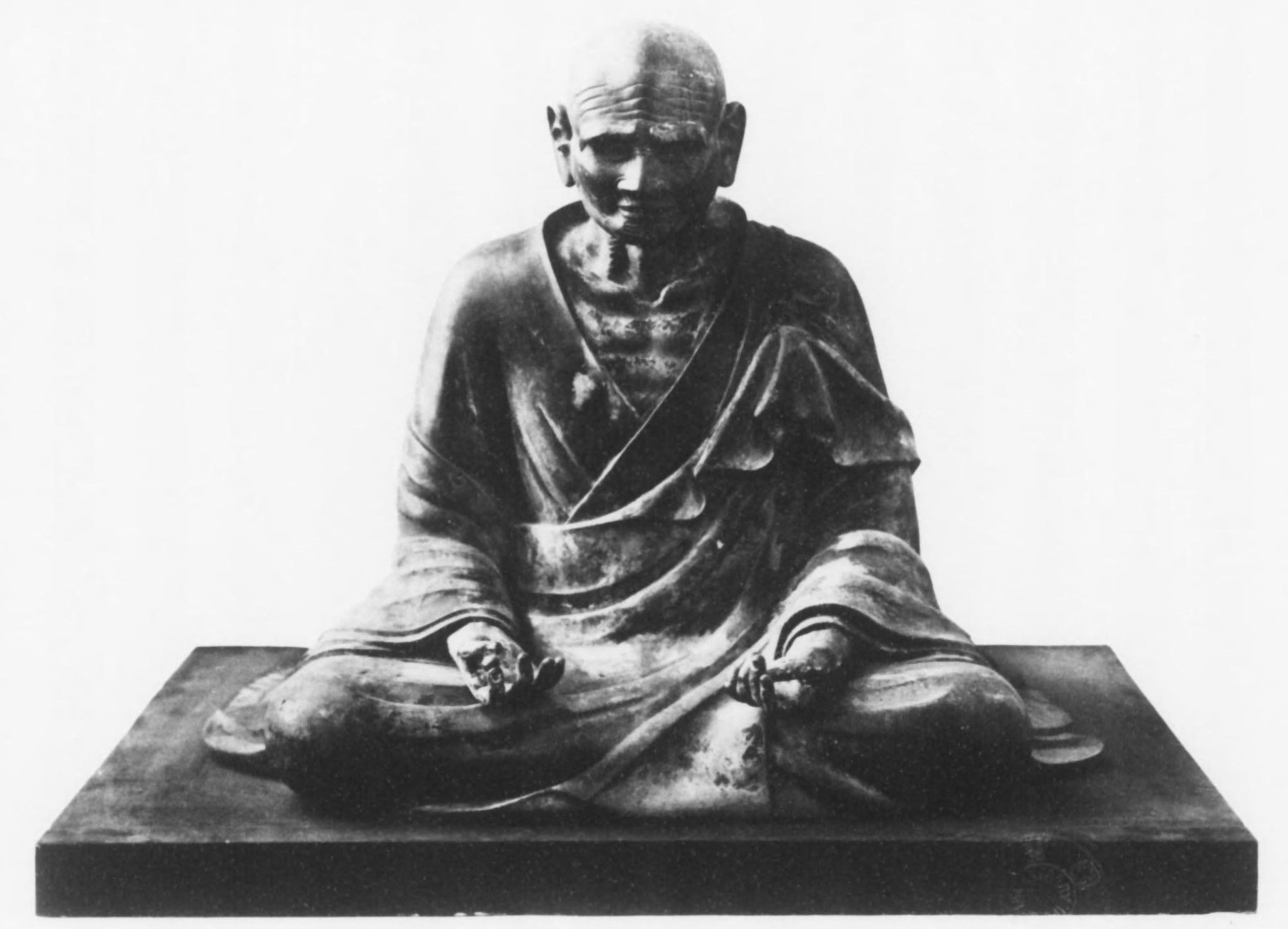

This is compounded by an account of his teacher, the Goguryeo priest known in Japan as Eiji, who greatly grieved that Shotoku Taishi had predeceased him. Eiji had returned to Goguryeo in 615, but when he heard of Shotoku Taishi’s death, he arranged a banquet in Shotoku’s honor, inviting various priests, and lectured on the sutras. In his prayers, he called out Shotoku Taishi—using the name Kamitsumiya Toyotomimi—and declared him a sage. He claimed he possessed the three fundamental principles, he reverenced the Three Treasures of Buddhism, and he helped people in need.

Eiji then made an ominous prediction, claiming that he, himself, would die on the 5th day of the 2nd month of the following year—that is to say, one year to the day after Shotoku Taishi. Then he would join his student and friend in the Pure Land. When he died on the day he predicted, the people declared that both he and Shotoku Taishi must have been sages.

This somewhat echoes an early story told about Shotoku Taishi, which took place in 613—the same year that he supposedly wrote parts of the Gangoji Garan Engi for Asukadera as well. In that year he was heading towards Katawoka when he encountered a starving man on the side of the road. He asked him his name, but the man did not—or could not—answer. Nonetheless, Shotoku Taishi had his servants provide the man with food and drink, and even gave him the clothes off of his own back to keep him warm. He left him there at the crossroads and the next day he sent his servants to check up on him.

Unfortunately, it seems the man had perished—he had been too far gone. And so, Shotoku Taishi told his men to build the man a tomb and to lay the body to rest there at the crossroads, which they did, no doubt wondering about why their boss was so concerned with a single person—and not even someone of consequence at that. This was a lot to spend on anyone, really.

A few days later, Shotoku Taishi had another odd request. He had his servants check the tomb. They found it was untouched since they had closed it up, and at Shotoku Taishi’s command they opened it and looked inside. To their astonishment, the tomb was empty, and no corpse was to be seen. However, the robes that Shotoku Taishi had given him were still there, folded up neatly and placed atop the coffin. The people realized that the man had been a sage and, as the saying goes, “A sage recognizes a sage”, and so it only added to Shotoku Taishi’s own fame.

Of course, even in death, the stories about Shotoku Taishi continued. First, he was buried in the Shinaga Tomb—the tomb that had been created to reinter his father. It is a little interesting that he was not given his own tomb, given how popular he was, but there may have been reasons for that. For one thing, he had not been expected to predecease Kashikiya Hime. If he was really born in 574, he was probably only about 48 when he passed away—still fairly young, all things considered, especially given how much he’d accomplished. They may not have prepared a tomb for him, yet, and so burying him in his father’s tomb may have been the best practice.

Of course, there is a lot going on with that kofun, in more ways than one. First off, the Shinaga Kofun appears to be a square kofun, similar to the Ishibutai kofun, which was thought to be the kofun of Soga no Umako. So why would Shotoku Taishi’s father—whom we are told was a sovereign, even if just for a brief moment—be buried in a square tomb and not a keyhole shaped tomb, like the other Ohokimi? Since we are talking about the legendary Shotoku Taishi, then we probably shouldn’t note that maybe his father wasn’t actually a ruler and maybe that was only something to help further prop up Shotoku Taishi’s own legend.

Whatever the reason, that is where we are told he was buried, and the area around the tomb even carries the name of “Taishi”.

Besides the burial, there were other ceremonies as well. One of them was by one of his consorts, Tachibana no Ohoiratsume. She was, herself, a royal princess, and we are told in some sources that they had both a son, Shirakabe, and a daughter, Teshima.

When Shotoku Taishi passed away, Ohoiratsume pleaded with Kashikiya Hime. She said, and I’m largely quoting the translation in Como’s work: “My lord must surely have been born into Tenjukoku, the Heavenly Land of Long Life. However, the shape of that land cannot be seen with the eye. I wish to have a likeness made so that I can have an image of the land into which he has been born.” This likeness was a tapestry, known to us as the Tenjukoku Shuuchou Mandala. It is an embroidery of an ideal Buddhist heaven, or Pure Land—although which one, nobody has been able to say with any certainty. Still, it is one of the few images that we have, other than statuary, from this period, and though much of it has faded or been lost, you can still see it today as it was restored in the Edo period by combining the surviving fragments with parts of a Kamakura era replica. It is kept at the Chuuguuji, the Temple of the Middle Palace. This mandala is not only an important link to the story Shotoku Taishi, it is one of the few—if not only—surviving pieces of embroidery from its time, and it is particular interest to scholars of the fabric arts, as the techniques used are distinctly different from those used in the later Nara period.

That temple of Chuuguuji was founded by, of course, you guessed it, Shotoku Taishi. We are told that the temple was originally built as a temple on his mother’s estate after she passed away. It was converted into a nunnery in the late Kamakura period and eventually moved to its present location, about 300 meters closer to Houryuuji. It houses not only the Tenjukoku mandala, but also Asuka era statuary, such as its own Miroku image.

From his death, the legend of Shotoku Taishi would only grow. It is often talked about as a Buddhist sect or even cult, and it seems to have been latched on to by various families, especially those with connections to the continent. Early on, the story of Shotoku Taishi was likely influenced primarily by Baekje descended immigrant family groups, but over time, the stories seem to be dominated by Silla descended groups, as pointed out by Como in his book on Shotoku Taishi. Temples like Shitennouji and Kouryuuji, both connected with Silla lineage groups in some way, seem to have had some sway over the stories associated with the Prince, as seen in some of the elements that can link back to various Silla stories. At the same time, Shotoku Taishi was also developed into a figure that helped further boost the legitimacy of the royal family.

We’ll discuss some of that as we try to pull apart some of the fact from fiction in the next episode. We’ll spend a little bit more time with Shotoku Taishi and his alter ego—Prince Umayado, aka Prince Kamitsumiya Toyotomimi.

Until next time, then, thank you for listening and for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Asuka, Sango (2015). The halo of golden light : imperial authority and Buddhist ritual in Heian Japan. ISBN 978-0-8248-3986-4.

Deal, William E. and Ruppert, Brian. (2015). A Cultural History of Japanese Buddhism. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. ISBN: 978-1-405-16700-0.

Kazuhiko, Y., 吉田一彦, & Swanson, P. L. (2015). The Credibility of the Gangōji engi. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 42(1), 89–107. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43551912

McCallum, Donald F. (2009). The Four Great Temples: Buddhist Archaeology, Architecture, and Icons of Seventh-Century Japan. ISBN 978-0-8248-3114-1

Como, Michael (2008). Shōtoku: Ethnicity, Ritual, and Violence in the Japanese Buddhist Tradition. ISBN 978-0-19-518861-5

Pradel, C. (2008). Shōkō Mandara and the Cult of Prince Shōtoku in the Kamakura Period. Artibus Asiae, 68(2), 215–246. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40599600

Matsuo, K. (13 Dec. 2007). A History of Japanese Buddhism. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9781905246410.i-280

Deal, William (1999). Hagiography and History: The Image of Prince Shōtoku. Religions of Japan in practice. Princeton University Press. ISBN0691057893

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Moran, S. F. (1958). The Statue of Miroku Bosatsu of Chūgūji: A Detailed Study. Artibus Asiae, 21(3/4), 179–203. https://doi.org/10.2307/3248882