Previous Episodes

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we are looking at the rule of Shiraga (aka Shiraka), aka Seinei Tennō. His reign, according to the Nihon Shoki, is fairly short, and, to be honest, mostly concerned with his successor—an important subject given that he never seemed to marry or have any children of his own. But rather than worry too much about that, this episode asks the question of just how much can we trust the Chronicles?

In particular, there is still the mess of the Five Kings of Wa, with Kō sending an embassy in 462, and then Bu sending an embassy in 478 that arrives in 479. The 462 embassy lines up nicely with what we read in Wakatake’s lifetime, but everything else lines him up with Bu. However, what if “Bu” were really Shiraga? What does that tell us? This is one of the things we’ll go into in the episode.

Not much more, here, I’m afraid. Go listen to the episode and feel free to reach out with any questions or let me know your personal theories? Whom do you like for Bu and Kō? Or do you subscribe to one of the other theories, such as the idea that they were from Tsukushi or even from the Korean Peninsula?

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is episode 65: The Party King of Wa.

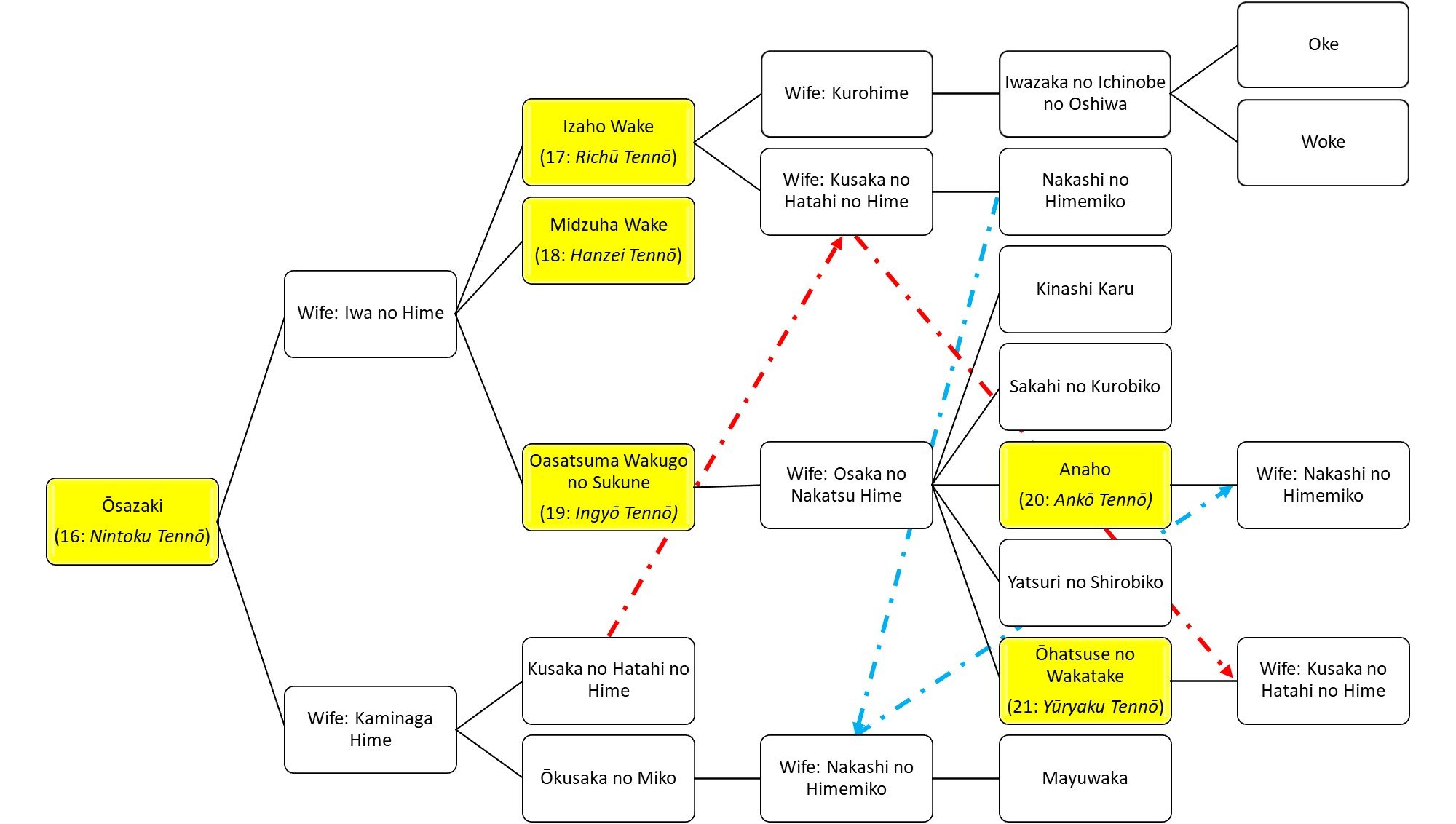

This week I want to talk about Shiraga Takehiko Kunioshi Waka Yamatoneko, aka Seinei Tennou, the son and successor of Wakatake or Yuryaku Tennou. And along with discussing Shiraga’s life, we will also revisit some of the continental historical sources that we’ve touched on previously, looking at how they line up with what we’ve learned about these past couple of sovereigns.

In looking at Shiraga’s life, I can't help but think of the contrast between expectations and reality. It is often easy for us to discuss historical subjects when we already know the outcome. We talk up the English king Henry VIII and even Henry V quite a bit, because we know what they did. But then there are others who are perhaps not as well known, or whose reigns were not such a success. How much attention do we pay them? After all, Wakatake could have been killed early on in the fighting with his brothers, and then he would be remembered merely for an attempted coup, rather than the larger-than life figure we know him as.

Also, it is often hard to see the details of those standing behind a shining light in history. Sometimes that light illuminates, but often it blinds us to the potential of those around them, much as the Chronicles’ focus on the royal line often obscures the details of the other people who were working, often just as hard, to build Yamato and the culture of the archipelago.

So I want to keep in mind here the potential that Shiraga demonstrates as much as what he actually accomplishes, and try, somehow, to look beyond the bright light cast by his father, Wakatake.

Okay, so what do we know about how Shiraga came to the throne, and why? Last episode we left off with the death of Wakatake and then Crown Prince Shiraga securing the throne through the assistance of his prime minister, the Ohomuraji, Ohotomo no Muroya, as well as Yamato-Aya no Tsuka. Their forces had surrounded the royal Treasury, where a would-be usurper, Prince Hoshikawa, and his brothers had barricaded themselves in and then set the whole thing on fire, burning everyone inside. And with that, Crown Prince Shiraga was able to take the throne himself, becoming the ruler known to us, today, as Seinei Tennou.

Of course, the Chronicles also suggest that Shiraga wasn’t exactly new to the throne. Well, maybe. The Nihon Shoki claims that he was appointed at the end of Wakatake’s reign, as Wakatake was on his deathbed. This contrast in accounts is a good reminder of how the organization of the Chronicles—particularly the Nihon Shoki—isn’t always something we can take for granted. I don’t necessarily trust all of the dates as given, and, while it does seem that more was getting written down at this time, there isn’t necessarily agreement between the different sources. I attribute this to a few things. First of all, without any other evidence, I suspect a lot of this was still being transmitted orally, stories about the period that were passed down. Although the Chronicles seem to aspire to the idea of an official history of the era, it is really focused on these stories—though sometimes the format of those stories is that they get broken up across different months and years and there is a bit of a detective work and even assumption that needs to go in there. We’ll talk about that a little later when we look at the continental sources.

But back to the Chronicles. Shiraga has now taken the throne, one way or another. But what is he inheriting, and what kind of monarch is he going to be? As we know, he was the son of Wakatake, whose exploits have become legendary. There were courtiers serving the Yamato court from across the archipelago—from Musashi in the east to the land of Hi in the west. They laid claim to rights over Kara, Nimna, Silla, and Baekje—however much those same states may have protested, if asked. Furthermore, Shiraga was entering with some background and experience. And advisors: He had Muroya to help him run things, as well as Matori, the Oho-omi of the Heguri.

And at the same time, there was a certain chaos in the world. Baekje was still finding its footing after being devastated by Goguryeo, and even the mighty Liu Song would fall around the time of Wakatake’s death, in 479. A savvy leader may have looked to such a power vacuum and seen an opportunity for growth and further expansion of the power of the state.

Alas, none of this would come to be. Whatever Shiraga’s ambitions were, it seems clear that he was unable to fulfill them, as his reign would only last a brief four to five years after the death of Wakatake. He did not exactly spend that time idly, however.

At first, his reign was similar to any other—he went about establishing a palace for himself at Mikakuri in Iware, in modern day Sakurai, traditionally held to be near the site of the eventual Fujiwara palace of Temmu. Here he affirmed the various court officials in their offices, and raised his mother, Kara Hime, up to the status of Grand Consort.

He also ensured that the burial rites for his father, Wakatake, were carried out and is said to have had his father buried in the Takawashihara Tumulus, in Tajihi, in the land of Kawachi. The tomb traditionally assumed here is a relatively small tomb—as far as kingly tombs go—in Fujiidera. Kishimoto suggests that the actual tomb referenced may in fact be slightly to the southeast—the Misanzai Kofun attributed to Tarashi Nakatsu Hiko, aka Chuuai Tennou. They say that there were Hayato who lamented night and day at the tomb. During this time it is said they refused food and water, and after seven days like this, they died. A special tomb was created for them just north of the main tomb mound, where they were buried with great ceremony—an act that sounds suspiciously like the act of offering human sacrifice at a burial.

And with that rather depressing episode of his father’s burial out of the way, there were some good times in the reign of Shiraga Ohokimi. For instance, there was a banquet thrown in the winter of 482, when the Omi and Muraji were both feasted in the great court and Shiraga just gave away presents of silk floss. The assembled nobles were allowed to take as much as they wanted. It is said that they went forth exerting their “utmost strength”. I can picture it now—bellies full of meat and heads full of sake, these nobles trying to find how they can lift and take out of the court as much silk floss as possible, draping it over their arms, rolling it into balls, and generally trying to find ways to make it manageable so that they could be the one to take as much as possible back, where it could then be used to weave silk fabric and more.

And then, a month or so later, came envoys from territories across the sea with gifts, and they, too, were feasted and received various presents—probably in emulation of the imperial Chinese courts, which seem to have placed great value on the idea of providing more to their guests than they actually received as a way to demonstrate their own wealth and power.

Of course, as if these parties weren’t enough, the entire realm would get in on it. In the summer of 483, Shiraga instituted a nation-wide drinking festival, which lasted five days. That’s not exactly Oktoberfest, but I can only imagine the wonders it did for the sake industry at the time. This may have been in imitation of the Han emperor Ming Ti, who reigned from 58-75 CE, or it just may have been an excuse to drink. This festival hasn’t exactly made it down to us intact, possibly because it was held in an intercalary month, so it really wouldn’t come around that often. That said, it isn’t like you need much of an excuse to go drinking in Japan, today.

There are other stories of Shiraga releasing prisoners, possibly Emishi and Hayato, who are said to have rendered homage, possibly in thanks for letting their people out of bondage.

And then finally, we once again see him partying with the functionaries and envoys from overseas, this time in the Hall of Archery, which was apparently a thing. They all shot arrows and apparently had a grand old time, with even more gifts being given out. And honestly, I don’t know where he’s getting all of these gifts. After all, didn’t they basically burn down the royal treasury after Shiraga’s brother, Hoshikawa, had basically gone in there and disbursed a lot of it already? But times must have been good.

To read the Nihon Shoki account, Shiraga seems like a party animal, and maybe he was—and is that such a bad thing? We at least aren’t given any reason to think he was just randomly killing people because he had a bad day, unlike his father—he isn’t even shown raising normal armies for much of anything. He seems to just be enjoying himself.

And of course, the problem, at least from the point of view of the royal line is concerned, was that he was only enjoying himself. There is no mention of a wife or consort. He doesn’t even seem to have had women that he longed for. Perhaps he just wasn’t into women—or possibly he was even what we might call asexual, today. Or perhaps there was something else altogether. All we know is that he is not mentioned as having taken a wife, let alone producing any heirs, and that was going to be a problem.

Sure, Shiraga could create a few Be groups—there’s the Shiraga no Toneri Be, the Shiraga no Kashiwade Be, and the Shiraga no Yugehi Be. And so he knew that his name would live on, but that didn’t help him with his main predicament. His half-brothers had died in Prince Hoshikawa’s attempted revolution, and Wakatake had killed all of his own brothers, so it wasn’t as if there was a first cousin out there that he could pass it to.

The line of Wakatake was coming to an end, and they had done such a good job of pruning the family tree, that it was hard to see how the royal lineage would survive. This may not have been front and center of Shiraga’s mind—no doubt he thought he had plenty of time left to figure something out, but the fates would have other ideas. He would die in the first month of 484, childless, probably around 40 years old.

He didn’t leave the throne without an heir, however. He may not have expanded the territory of Yamato through conquest, nor had any great technological leaps during his reign, but he does appear to have kept things together and performed at least the most basic of functions of a dynastic monarch: Secure the throne for the next generation.

But who was the next generation? If Shiraga didn’t have kids, where did they come from? Did he just find some kids out in the street and say, “Hey, you… Wanna be the next sovereign of Yamato?” After all, there were rules to these things, weren’t there?

Well, we will discuss all of that in the next episode, when we talk about the brothers Woke and Ohoke and their sister, the would-be sovereign. So, that’s a little bit of a cliffhanger to leave you on.

But before that, I mentioned that we’d take another look at other records and resources of the time – those from the continent as well as the Japanese Chronicles, and also archeology – and see what they tell us in light of everything we’ve learned about Anaho, Wakatake, and Shiraga’s reigns. I know I’ve mentioned some of this before in episode 58, but it is once again very relevant, in addition to being pretty darn interesting, when we think about Shiraga taking the throne in 479 and leaving it in 484. So let me lay it all out again.

So first off, we have archeological evidence of the reign of Wakatake, aka Wakatakiru, through a couple of swords, one from Eta-Funayama kofun in Kumamoto, and the other from Inariyama kofun in Saitama. The latter is dated to either 411, 471, or 531 – that’s that wiggle room because of the sixty-year calendrical cycle - and claims that the individual referenced in the sword inscription served in Wakatake’s court. So one assumes that by 471, at least, there was a sovereign named Wakatakiru in Yamato, and he had enough influence to attract courtiers from across the archipelago. Wakatake’s entry in the Nihon Shoki has him ruling from 456 to 479, so that tracks with the 471 date so far.

Furthermore we previously discussed the Five Kings of Wa named in the records of the Liu Song. There are two kings that could theoretically reference Wakatake, assuming the dates of his reign in the Nihon Shoki are correct. Those are the Kings named “Kou” and “Bu”.

Here’s what the History of the Song has to say for both of them. This translation is largely thanks to Massimo Soumare’s translation in his book, “Japan in Five Ancient Chronicles”. It goes something like this:

“Sei died.

“His heir was Kou, who sent ambassadors and offered tribute. In the sixth year of the Daming era of Shizu (which is to say, the year 462), it was proclaimed by imperial edict: “Heir to the king of Wa, Kou – for generations you have shown your devotion and have built a domain in the open sea. You have received the influence (of China) and you pacify your borders. Respectfully, you bring tributes. Recently you have inherited the kingdom. It is our duty to benevolently grant you courtly rank and make you general and pacifier of the east and King of the Land of Wa.”

So that was Kou. It is implied that he was the heir to Sei, who sent their last embassy around 451, some eleven years prior. And the court granted the titles of general and pacifier of the East and reaffirmed his title as the King of Wa. And then we have little more. There is simply a note that he died and then we get the next entry:

“His younger brother Bu then rose to power. By himself he took the titles of regional military governor for the military affairs of all of the seven lands of Wa, Baekje, Silla, Nimna, Kara, Jinhan, and Mahan; great-general and pacifier of the east; and king of the land of Wa. In the second year of the Shengming era of Shundi (which is to say, 478) he sent ambassadors and had the following letter delivered: “My land is in a land far away, and I have built a domain in a remote place. From ancient times, my ancestors, donning armour themselves, travelled and crossed mountains and rivers. Without a single moment of repite in the east they conquered fifty-five countries of the hairy people, and in the west they subdued sixty-six countries of many barbarian people. Crossing the sea, they pacified ninety-five countries of the northern sea. They made the royal roads secure, extended the land, and brought far the borders of the emperor’s domain. For generations, they have been granted audiences and they have never strayed from the straight path. Despite being unworthy, I gratefully inherited the achievements whose measures reach the boundaries of the heavens, and passing along my road far away through Baekje, I armed the ships. And yet Goguryeo has no virtue, and craving destruction, assaults the people on the borders and does not cease to kill. We always delay, and therefore we lose glory.

“And even if we proceed on the road, sometimes we pass and sometimes we do not. My late father, Sei, grew greatly angry that the enemy was holding the heavenly road and assaulting us. One million bowmen were moved by the voice of justice and gathered, but I suddenly lost my father and my older brother, and even though the enterprise was at hand, I had to desist. I observed the mourning and did not move the army. Therefore, lying down, I slept and still I achieved no victories. Now making armour and deploying the army, I wish to proclaim the will of my father and senior brother. Justice-loving men, heroes, men of letters, and warriors ply the whole of their valour, and even in front of naked swords do not retreat. If, with the protection of the virtue of the emperor, my difficulties are solved by destroying this strong enemy, there will be no change in the previous acts. By myself, I set up a governing office and a titles similar to the one of Sangong was granted to me, and a charge given to my underlings: Even more will my fealty be strengthened.

“By imperial act were given to Bu the offices of regional military governor for the military affairs of all of the six countries of Wa, Silla, Nimna, Kara, Jinhan, and Mahan; great-general and pacifier of the east; and King of Wa.”

So based on these Liu Song records, King Bu was the brother of King Kou, and son of Sei. Kou appears as an inheritor of a rather martial lineage, making claim to peninsular rights, and claiming to wish to chastise Goguryeo itself—currently a powerful force that had only recently destroyed their rival, Baekje.

So why does this matter in an episode ostensibly about Shiraga?

Well, if Bu is Wakatake, as many take him to be – for understandable reasons, given how martial his reign is described as - then honestly, not much. But there is at least one theory out there that proposes that Wakatake was actually Kou, and Shiraga was Bu, which opens up a whole new series of questions and possibilities.

Now, as we heard, King Kou sent an embassy to the Liu Song which arrived in 462, while the embassy from Bu arrived in 479. Both of these dates do fall within the window of Wakatake’s reign, and on the face of it I have to admit that Bu as Wakatake makes some sense. After all, he did take over from his brother, Anaho, according to the Chronicles—though that does skip over Ichinohe and whatever his position was. Furthermore, the warlike and expansionist nature feels very much like Wakatake.

Furthermore, many people associate “Bu” with Wakatake, since the character “Bu” can be read as “Take” or “Takeru” in Japanese. And so people make the seemingly logical conclusion that the Liu Song chroniclers must have been using the latter part of Wakatake’s name to refer to him.

Except, that neither of the inscriptions we have of Wakatake’s name actually use that character—they both spell “Wakatakiru” phonetically. Furthermore, these were court officials, so one imagines that if there was anyone who knew how to spell Wakatake’s name, it would have been them. Even with the Chronicles, it isn’t certain: in fact, only the Nihon Shoki uses the same character for “Take” as the Song records do for “Bu”. The Kojiki uses something else entirely. This doesn’t mean Wakatake couldn’t be the same as Bu, just that I find the reasoning somewhat shaky.

However: Shiraga’s full name is given in the Nihon Shoki as Shiraga Takehiro Kunioshi Waka Yamatoneko, and the “Take” in Takehiro *is*, in fact, the same character as King “Bu” from the Liu Song records. We don’t have any swords with his name inscribed, from the period, so we can’t actually judge how they spelled it at the time, but could the King Bu, whose embassy arrived in 479, actually be Takehiro, aka Shiraga?

If we try to say that Bu is actually Shiraga, then we are left with a conundrum: was Shiraga actually Wakatake’s brother, vice his son? Or was Wakatake the one here termed “Sei”, instead? After all, Bu says it is his father who grew angry and gathered men to fight Goguryeo after they had “assaulted the people on the borders”—possibly referring to their destruction of the Baekje capital of Wiryeseong. Wakatake had certainly attempted to subdue Silla, at least, and there were the troops sent to help put the Baekje heir on the throne.

There are a couple ways to square this circle, and with it I think we get more information not just on Wakatake, but possibly on his heir, Shiraga. First off, let’s return to the idea that Wakatake is actually Bu. That would imply that Kou was actually Anaho, who must have reigned for a good bit longer than we are otherwise led to believe. Or perhaps Kou was Ichinohe, his cousin in the Chronicles—it may even be that Ichinohe or Anaho reigned alongside Wakatake for a bit as co-rulers. If that is the case, then we expect that Anaho or Ichinohe had just come to the throne in 462. That throws off a lot of our dates in the Nihon Shoki, and cuts Wakatake’s reign down even further—but it isn’t impossible.

Our second option is to take Wakatake as the last of the five kings, Kou. Per the Nihon Shoki, he would have still been somewhat new to the throne in 462. Realistically, that embassy was probably sent in 461, and would have taken a while to organize, so it is possible that it was sent while he was, indeed, new to the throne. This also appeals to me for its sense of timing. Multiple rulers had, at this point, sent tribute to the Song court and been recognized as Kings of Wa.

Which raises the question: Why would they have done such a thing? What was in it for them?

From what I can tell, we don’t seem to be in the era of regular communication and official diplomatic trade, though that likely did happen on these trips. It had to have been quite the journey, particularly at the time. Fortunately, we do have some information on these, mainly from the Song records themselves. While these records make some mention of tribute, they seem primarily concerned with the matter of titles. Kings of Wa would often declare their titles and ask for the court of the Liu Song to affirm them. These were often titles granting nominal overlordship to the Japanese archipelago and parts of the Korean peninsula. Multiple rulers had, by this time, received titles from the Song Court.

It would make sense that a sovereign would organize an embassy in the beginning of their reign to help solidify and legitimize their rule. In fact, I suspect it was becoming somewhat routine that when a new ruler would take the throne, there would be a period of internal shuffling while the court made sure that the ruler would last, probably putting down several attempts by various chieftains to break away or other royal family members to take the throne—a process that could take several years. After all of the dust settled, an embassy would be gathered and sent out—in this case to the Song court. That would allow for external validation of Yamato’s kingship process and likely bring back a healthy amount of continental goods that could be doled out in return for loyalty, as well.

It makes less sense to me that there would have been an embassy sent by Wakatake near the end of his reign, around 478. By the way, the history of the Southern Qi actually records that this embassy was in 479, which may be accounted for if one reads the Song records as saying when it was sent, vice the Southern Qi records as to when it arrived. Given that it was in 478, it is certainly possible that Wakatake’s illness may not yet have set in, and he may have still been quite healthy. It is also possible that, with the failure against Silla, he was indeed looking for the Song to support his ambitions on the peninsula, hence a second embassy was a smart political and diplomatic move.

Alternatively, one could also read this as a mission sent under Shiraga. Again, it would have been around the start of his reign, which makes sense—especially if he was made a co-ruler early on. Much of the violence ascribed to King Bu could be attributed to Wakatake’s reign and earlier, and it is entirely possible that Shiraga had planned to continue Wakatake’s campaigns on the peninsula and was looking for assistance from the Song or anyone else at the time. If that is the case, however, then perhaps either the Nihon Shoki or the Records of the Liu Song made a mistake in the familial relationship between either Kou and Bu or Wakatake and Shiraga.

Personally, I’m somewhat inclined towards the idea of Kou as Wakatake and Bu as Shiraga. While Wakatake certainly was the more warlike of the two, that may not have been known at the time that he sent his embassy. Similarly, Shiraga may have had grand plans to emulate Wakatake, who had certainly done his part to bring everything together. Who knew how it would turn out? At the same time, I acknowledge that there is a large amount of consensus around the idea that Wakatake is Bu, perhaps writing to Song at the height of his power.

Of course, either way, these embassies mattered little in the outcome, for, as I mentioned before, the days of the Liu Song were numbered. Their dynasty would fall, replaced by the Southern Qi dynasty. The actual record of the Song Dynasty was then compiled in this time; the first edict to record the history of the time was in 488, and it may not have been completed until sometime around 492 or 493. Given that it was building a story from the Song Records, it is entirely plausible that certain details may have been misremembered or misquoted.

How about what the Japanese Chronicles have to say on the matter? There is mention during Wakatake’s reign of contact with the continent and embassies to what we can assume was the Liu Song court around 462, but none after that. This leads me to believe that either the Chroniclers knew about the Song records and decided to associate Wakatake with Kou, or else there was another record of a visit around 462. In either case, it appears that the Chronicles, drawing from the Liu Song records, are associating Wakatake with Kou, if anything.

There is also the issue of Wakatake’s dates. There seems to be a general consensus that the dates from at least 462 to 479 would belong to Wakatake’s rule. If Wakatake is Kou, the dates in the Nihon Shoki would seem to work out just fine, especially if we assume that he and Shiraga were co-rulers for some period of time. On the other hand, if Wakatake is Bu, then there had to be some other ruler in 461 who had just come to the throne—again, possible if it was one of his relatives whom Wakatake then killed, possibly shortly afterwards.

And at this point I feel a bit like Rosencrantz and Guildenstern attempting to tell if the wind is southerly. In truth, there probably is no way of knowing unless some new and miraculous piece of evidence comes to us from the depths of the past.

It does, however, speak to my point, early on, about potential. It is so easy to forget about the potential and only to look at what was accomplished. The picture the Chronicles paint of Shiraga pales in comparison of their description of Wakatake. Whereas Wakatake was mercurial and violent and known for many great deeds, Shiraga feels only a little better than a placeholder. He is almost like Waka Tarashi Hiko, aka Keiko Tennou, who also died childless and would have to pass the throne to a different line. In fact, his biggest accomplishment, which we’ll go into next episode, was finding an heir. And so it is easy to overlook him.

But what if—what if he is Bu? What if that fiery speech and arrogant assumption of titles was this very same Shiraga Takehiko? He may not have lived as long, and his ambitions may never have lived up to his potential, but that doesn’t mean we should discount him altogether.

Similarly, there are all those we hear little to nothing about. Which of the supposed usurpers might have actually been the rightful heir to the throne, much as Ichinohe, only to have their potential stolen by another? Remember, history loves a winner, and it is the winners who get to shape it. But when we actually put ourselves there, not in the time of the chroniclers but in the time when these actions were taking place, history was not yet written. It was still to be. And for the countless people living in this time, there was no certainty of what was to come. The person they saw as their hero may come down to us as a villain. The person they were sure would be “most likely to succeed” may never be written about. Perhaps they didn’t live up to their potential, or perhaps they just didn’t live—it wasn’t necessarily the safest time to be alive.

So many stories out there, but we only have the one here, so that’s what we will continue to focus on.

Anyway, thank you for listening and letting me take this little diversion. It has honestly been something sitting in the back of my head for most of Wakatake’s reign and especially as I read through Shiraga’s own story. And now I can leave it here and move on to the next part of our narrative, as we figure out just who was going to succeed the childless Shiraga.

So until next episode, thank you for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

And thanks to those who have been talking us up on places like Facebook and Reddit and elsewhere. I don’t always have a chance to respond, but it is nice to see references out there, so thank you!

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com. We would love to hear from you and your ideas.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7.

Kim, P., & Shultz, E. J. (2013). The 'Silla annals' of the 'Samguk Sagi'. Gyeonggi-do: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Kim, P., Shultz, E. J., Kang, H. H. W., & Han'guk Chŏngsin Munhwa Yŏn'guwŏn. (2012). The Koguryo annals of the Samguk sagi. Seongnam-si, Korea: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Soumaré, Massimo (2007), Japan in Five Ancient Chinese Chronicles: Wo, the Land of Yamatai, and Queen Himiko. ISBN: 978-4-902075-22-9.

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253.

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3.

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1