Previous Episodes

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we’ll recap what we talked about in the past year, 2021, and the various episodes. Hopefully this will bring back reminders of a few of the things that happened, but it won’t be everything, so check out the Archives for more. Below I’m including as many of the references as I can from the episodes this past year.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan, and from all of us here:

Akemashite Omedetou Gozaimasu!

May you all have a bright New Year!

As we release it is the start of 2022, and this episode we are taking a short break from our regularly scheduled programming. We’ll be back next episode with the continuation of the Chronicles, but I figured we could celebrate the new year with a quick recap of some of the highlights of the past year’s episodes, which have taken us from the latter half of the third century into the mid-5th century. Our earliest stories are legendary accounts of ancient heroes, set during the fairly opaque events of the early kofun period. As time progressed, we start to see greater correlation with external historical sources, and some idea of what may have been happening.

This past year started by finishing up the story of Ikume Iribiko, the second sovereign in the Iribiko dynasty in the Makimuku region, aka Suinin Tennou. If Ikume actually existed, he probably lived some time in the late 3rd century, during the height of the Makimuku court, in Yamato, at the foot of the holy Mt. Miwa. Many traditions claim an origin during this time, from court ritual to sumo and even the founding of Ise Jinguu.

We also see some interactions with the continent, but they are more about individuals bringing in specific goods, rather than any kind of real state-to-state relations.

Of course, following Ikume Iribiko we get Ohotarashi Hiko Oshiro Wake no Mikoto. Although he’s generally included with Mimaki and Ikume as part of the Iribiko dynasty, some have suggested that Ohotarashi more properly belongs to another dynasty—possibly one based out of Tsukushi, aka Kyushu. Certainly many of his military conquests were in that area, fighting groups like the Kumaso, the Hayato, and the Tsuchigumo—or earth spiders.

Ohotarashi Hiko’s campaigns in Kyushu are later echoed in the tale of the legendary warrior, Yamato Takeru, who was the subject of Episode 34 and 35. Many doubt that Yamato Takeru was an actual person, suggesting that he was a composite hero-figure whose exploits were a mélange of other warrior figures. Nonetheless, his story persisted throughout history.

Of course, it wasn’t all about conquest. Many of the stories are about family relations, and that’s important, even if it isn’t always as immediately exciting. While these relationships are often portrayed as sexual conquests by the sovereign, it nonetheless gives us an idea of other types of political connections that were being built between the elites around the country.

Now, while the Chronicles focus on the lives of the sovereigns—real or otherwise—we do get the occasional look into the lives of other important figures. One such figure is Takechi—or Takeuchi—no Sukune. He is the first prime minister, or Oho’omi, of the Yamato court, and we first met him back in Episode 38. He was supposedly born in the reign of Ohotarashi Hiko and was a trusted advisor for the next four or five sovereigns. Not only is it interesting to see an individual of such renown outside of the royal line in these old stories, but it also gives us some possible bounding around the dates for their reigns, which were likely much shorter than the dates the Chronicles tend to give them. In all likelihood he was prominent around the mid to late 4th century.

These early years, from what we can tell, saw increased contact with the continent, and various expeditions throughout the archipelago. While Yamato may have spread the Miwa faith throughout the islands, through which they exerted influence, the archaeological record shows that we are still a far cry from what we would call an actual state, despite the grandiose language of the Chronicles. Rather than a single state, there were various proto-states expanding their influence in various regions, such as up north in Izumo, and in the nearby region of Kibi.

Meanwhile, similar processes were at work on the Korean peninsula, but with a few different influences. For one thing, the peninsula stood at the edge of the Jin empire, and the commanderies that had been set up there in the Han dynasty had maintained a presence in the region. This both brought many of the technological and bureaucratic developments to the peninsula while at the same time impeding the growth of other polities. In the early 4th century, however, the Jin had become weakened by internal strife, while Goguryeo was growing. Goguryeo forces eventually overwhelmed and conquered the commanderies, ending direct influence by the Jin dynasty.

With the fall of the commanderies, we see the growth of new states on the peninsula. Perhaps the most notable are Silla and Baekje. Silla’s early state appears as a confederation of about six city-states that eventually formed a locus of power around the area known today as Gyeongju, while Baekje nobility likely descended from individuals who had fled the Goguryeo court for some reason and then consolidated the individual polities of the Mahan confederacy.

As these states form, we start to see greater and greater interaction with the Wa, the people on the archipelago. It seems clear from the various stories that the Wa people were skilled navigators with ships that could easily raid up and down the coast of the Korean peninsula. Of course the Japanese Chronicles portray these attacks as conquest, and we examined much of that in Episode 40, as we discussed Tarashi HIme and her so-called “Conquest” of Korea.

It should be noted that many doubt the existence of Tarashi HIme, aka Jingu Tennou, but it nonetheless seems clear that ties between the archipelago—whether directly through the Yamato court or as individual polities—and the peninsula were a mix of diplomacy, piracy, and everything in between. Events at this time set up the general relationships, with Baekje allied with Yamato, and Yamato often raiding Silla, though the social and political exchanges were much more fluid and complex.

Meanwhile, back at home, things were not going too well. There was no system of primogeniture in Japan, and so when a sovereign died there was no guarantee that his designated heir—if he had one—would be the one to assume the throne. The war to secure the throne for the young Homuda Wake was just the first such succession dispute to be had, and, as we would see, it would become more or less the norm for the death of a sovereign to lead to some form of chaotic situation.

At the same time, we started seeing some actual ties to history. For example, in Episode 42 we talked about the Seven-Branched sword that was found at Isonokami Shrine, and which seems to match up with a gift from Baekje recorded in the Chronicles. It gives us a date of about 369 to 372, and matches up with some of the entries in the Nihon Shoki referencing the Baekje Annals: history from Baekje that had been part of the works drawn upon to compile the Nihon Shoki in the first place. Of course, there are still many questions as to just who the sovereign actually was at this time, not to mention differences between the Korean and Japanese stories about the period, but it does seem to lend credence to diplomatic ties of some kind, and to the idea that the “Wa” may have actually referred to Yamato—or at least confederation of Yamato and its allies—more often the not.

It isn’t just decorative swords that came over during this period. We also see other continental advancements, including domesticated horses and writing. Now it is true that we find writing in the archipelago from much earlier, but as David Lurie has pointed out, it doesn’t exactly indicate any kind of actual literary tradition or culture. But with scholars from Baekje we are told that they started teaching people to read and write, which also means that they could start writing down their history. Of course, we don’t know how much of that written history survived for the Chroniclers to use, but we can start to see a change in the tone and tenor of what is being written down.

Still, however, some of our most reliable information for this period comes from outside of the archipelago itself, and as we turn the corner into the early 5th century. It was at this time that a stele was erected at the tomb of Goguryeo’s King Gwangaetto the Great, who reigned from 391 to 413, and which we talked about in Episodes 44 and 45. In it, the Wa are mentioned numerous times, and it gives another view of the relationship between the Wa, Baekje, Silla, and Goguryeo. Important at this time is the story in both the Baekje and Japanese chronicles that Prince Jeonji of Baekje was actually sent to the Yamato court as a sign of friendship, and possibly to protect him from Goguryeo and any enemies he might have had in the Baekje court as well. He would eventually return to Baekje with an honor guard of Wa troops who would help ensure he took his rightful place on the throne.

Of course he wasn’t the only prince sent to the Yamato court, and another famous prince, Misaheun of Silla, was also sent, though seemingly under a bit more duress. Misaheun’s eventual departure was on much less amicable terms than that of his Baekje counterpart.

During all of this, we learn about Katsuraki no Sotsuhiko, a powerful figure who shows up in many of these stories. Sotsuhiko is described by the Japanese sources as merely a vassal of the sovereign, but there are indications that he was more independent than that. Given that his daughter, Iwa no Hime, would eventually marry into the royal line and produce heirs to the throne—something that was otherwise restricted to women of royal lineage—it would seem that he was a bit more than just a vassal.

Most of this takes place during the reign of Homuda Wake, better known as Oujin Tennou, though there is some confusion, especially between what is happening in Homuda Wake’s reign and what is happening in the reign of his mother, Tarashi Hime, likely indicating that many of these were stories unmoored from a specific year that the Chroniclers had to figure out how to place in something resembling chronological order.

This may also have been further confused by the assumption by the Chroniclers in the 8th century that kingship had always been in the same model—that there was a single sovereign and that rulership went back in an unbroken line to the original progenitor. However, there are several things that suggest that rule under a singular autocrat was a more recent development.

First off, there is the fact that despite plenty of evidence for female sovereigns, from Himiko in the Wei Chronicles, to Tarashi Hime and then the women rulers from the start of the 7th century onward. Many of the early stories are about pairs of elites—either an elder and a junior or else a male and a female.

On top of all of that, Kishimoto Naofuji pointed out that the kofun themselves show evidence of at least two separate but chronologically co-incident lineages of elites. This suggests, in part, that there were two “co-rulers” at any given time—one that handled ritual and spiritual matters while the other may have been involved in more administration and bureaucracy. If that is the case, it could mean that some of the rulers were actually co-ruling together, which would certainly explain how it could be hard to pin some events down to a single reign.

Of course, that also means that some co-rulers may have been dopped from the lineage completely, especially female rulers who may have been portrayed merely as the wife of the sovereign rather than the dynamic and politically active figures that they likely were.

Now following Homuda Wake’s death, there was another period of chaos. The throne went empty for years as brothers fought over just who would sit in it. For more on this somewhat bizarre dispute, and more references to Kishimoto’s theories, see Episode 49.

Eventually, however, the throne went to Ohosazaki no Mikoto, aka Nintoku Tennou. During his reign, we see famine, public works, and the one of the earliest ice houses. There are the obligatory stories of his love life, but also many other stories about various events, which honestly could have happened just about any time, and there is very little to actually tie it to this sovereign. Still, we can learn a lot. For one, the public works were often about things like irrigation and flood control—building canals, ponds, etc. Wet paddy rice agriculture relies a lot on regulated seasonal flows. Too much, and the paddies can be washed away, but not enough, and they dry up.

We also see disputes over “rice land”, a concept that would be key to the country’s eventual economic basis. The idea that control over the rice-producing land, and that certain lands were dedicated to produce rice or equivalent goods for a given elite or institution, is an idea that would be critical in later centuries. Likewise, being given charge of such land would come with certain benefits in terms of remuneration.

This is also about the time that we see a term pop up in the Chronicles for the sovereign: “Oho-kimi”. Often translated as “king”, which is actually the sinographic character used in the Chronicles, this appears to have been the ancient title for sovereigns. We know that “Kimi” often shows up as a kabane, or ancient title, for a person or family who were in charge of a large land or country, and so it seems that “Oho-kimi” would logically be an extension of that term, though it isn’t exactly clear that the two are correlated. There are a lot of these old terms, such as “Wake” and “Hiko”, which often show up as though they are name elements when in reality, they were probably ancient titles.

The other title used for the sovereigns throughout is “Sumera no Mikoto”, aka “Tennou”, but this is a term that wouldn’t actually come to be used until the 7th or 8th century, and as such is entirely anachronistic, and I try to avoid it. In fact, as I’ve mentioned in the past, I try to avoid the common term, “Emperor”, because that is an English translation for “Tennou” from a very different period and for very specific reasons that doesn’t necessarily describe the kind of rulership that we are seeing develop in the archipelago. Even “King” may be questionable, as rulership was not necessarily analogous to the kings and queens of Europe and their surrounding environs. As such, you’ll notice I try to rely on “Sovereign” where I can.

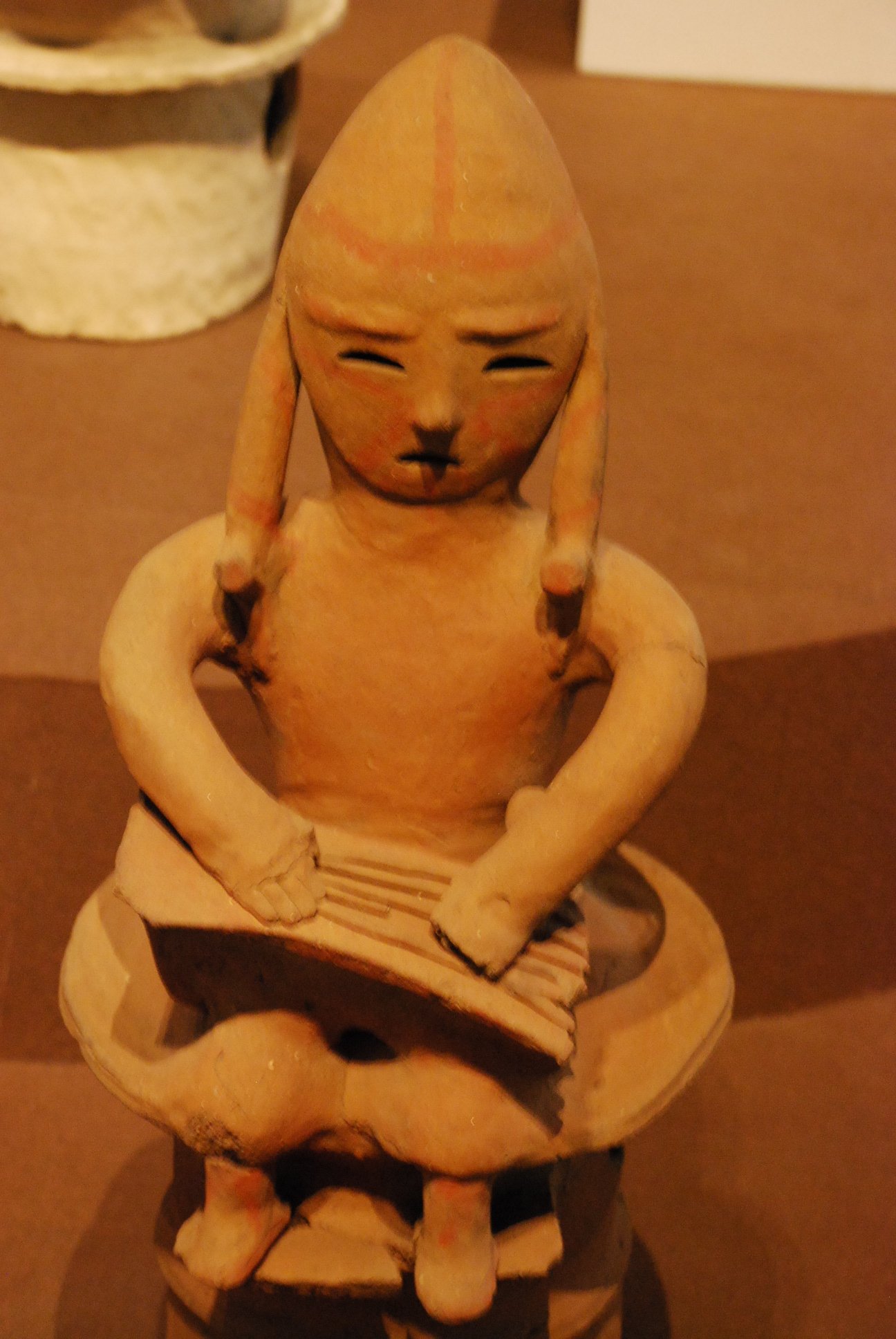

Now when Ohosazaki no Mikoto passed away, we are told that we was buried in a grand kofun. Modern tradition states that this is Daisen kofun, the largest kofun in the world and one of the three largest mausoleums in the world—larger than the great pyramids in Egypt and on par with the tomb of Qin Shihuangdi in modern Xi’an. This past year – aka 2021 – they even began new studies of Daisen kofun and its construction, and even if it isn’t the tomb of Ohosazaki, it dates from around the correct period, making it an important clue about what was happening in the 5th century. These giant tombs likely took years to build, and were probably started during the sovereign’s lifetime. While today they are typically covered in trees and forest, when they were new they were likely barren, covered with rocks and sand and rimmed with round clay haniwa. Some of these clay cylinders may have even been topped with bowls and various statuary of boats, houses, and more—though actual human figures would only just start to get popular in the 5th century.

From Ohosazaki no Mikoto, the lineage continues with another period of chaos and the reigns of Izaho Wake and then his brother, Midzuha Wake, aka Richu and Hanzei Tennou. After Midzuha Wake’s death, the throne went to Oasatsuma Wakugo, aka Ingyo Tennou. Oasatsuma is intriguing for several reasons, not the least of which is that he is said to have been unable to use his legs due to a disease in his childhood. He is said to have initially refused the throne, but the ministers at court actually pressed the issue. He did eventually take it, however.

And with that, we are caught up. In the next year we will continue on our journey. In the coming year, well, I honestly don’t know everything that we’ll talk about, but I can hazard a few guesses. First, I know we will talk about the Five Kings of Wa mentioned in the Book of Song, and how they map onto the sovereigns as we know them, but to do that we have at least one more reign to talk about. I also suspect we will start talking more this year about the continent and what is happening. In the 4th century, Buddhist teachings had already made it from India to Korea, and in the 5th and 6th centuries, the trade routes north and south of the Taklamakan desert would become conduits for further teachings to travel across, eventually making their way all Japan—officially in the 6th and 7th centuries, but possibly even earlier. Before that happens, we’ll start to get a better idea of what is going on as the state of Yamato as it consolidates its rule and traditions across the archipelago. We’ll pay attention to the formation of the kingship in Yamato and what would eventually be termed Japan.

And that is just a few of the places we’ll go. Next episode, we’ll finish up Oasatsuma Wakugo’s reign. Until then, thank you for all of the support that you have given this podcast. It is really just something that I started in part to satisfy my own curiosity and I’m touched that others find it of interest as well. The past couple years have been rough on many of us, and has been nice to have this project to keep me going. Also, a special shout-out to my wife, who has not only put up with all of this, but who helps to edit the scripts I type up, often on short notice. Her assistance and help has been invaluable.

Finally, a special thanks to all of those who have donated to support us and help keep this thing going. Dvery little bit helps to keep this running without the need to resort to advertising or something similar, so thank you. And I do hope to keep it going for many years to come.

And so, with that, may I wish you a bright and auspicious New Year from all of us here at Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

- (2020). Website: 仁徳天皇陵古墳百科. Last visited 14 October 2021. 文化観光局 博物館 学芸課. https://www.city.sakai.lg.jp/kanko/hakubutsukan/mozukofungun/kofun.html

太田蓉子. (2020)「葛城」を詠んだ万葉の歌. http://www.baika.ac.jp/~ichinose/o/20211125ota.pdf

Yōko, I. (2019). Revisiting Tsuda Sōkichi in Postwar Japan: “Misunderstandings” and the Historical Facts of the Kiki. Japan Review, (34), 139-160. Retrieved April 24, 2021, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/26864868

Barnes, G., & Ryan, J. (2015). Armor in Japan and Korea. Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures, p. 1-16. DOI: 10.1007/978-94-007-7747-7_10234

Lee, D. (2014). Keyhole-shaped Tombs and Unspoken Frontiers: Exploring the Borderlands of Early Korean-Japanese Relations in the 5th-6th Centuries. UCLA. ProQuest ID: Lee_ucla_0031D_12746. Merritt ID: ark:/13030/m52j7s88. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7qm7h4t7

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Scheid, B. (2014). Shōmu Tennō and the Deity from Kyushu: Hachiman's Initial Rise to Prominence. Japan Review, (27), 31-51. Retrieved August 10, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23849569

Kim, P., & Shultz, E. J. (2013). The 'Silla annals' of the 'Samguk Sagi'. Gyeonggi-do: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

KISHIMOTO, Naofumi (2013, May). Translated by Ryan, Joseph. Dual Kingship in the Kofun Period as Seen from the Keyhole Tombs. UrbanScope e-Journal of the Urban-Culture Research Center, OCU, Vol.4 (2013) 1-21. ISSN 2185-2889 http://urbanscope.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/journal/vol.004.html

Yoshie, A., Tonomura, H., & Takata, A.A. (2013). Gendered Interpretations of Female Rule: The Case of Himiko, Ruler of Yamatai. U.S.-Japan Women's Journal 44, 3-23. doi:10.1353/jwj.2013.0009.

Vovin, Alexander (2013). “From Koguryo to T’amna: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean”, Korean Linguistics 15:2, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa

Kim, P., Shultz, E. J., Kang, H. H. W., & Han'guk Chŏngsin Munhwa Yŏn'guwŏn. (2012). The Koguryo annals of the Samguk sagi. Seongnam-si, Korea: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Kawagoe, Aileen (2009). “Did keyhole-shaped tombs originate in the Korean peninsula?”. Heritage of Japan. https://heritageofjapan.wordpress.com/following-the-trail-of-tumuli/types-of-tumuli-and-haniwa-cylinders/did-keyhole-shaped-tombs-originate-in-the-korean-peninsula/. Retrieved 8/24/2021.

Bentley, John R. (2008). “The Search for the Language of Yamatai”. Japanese Language and Literature (42-1). 1-43. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/30198053

Jeon, H.-T. (2008). Goguryeo: In search of its culture and history. Seoul: Hollym.

Rhee, S., Aikens, C., Choi, S., & Ro, H. (2007). Korean Contributions to Agriculture, Technology, and State Formation in Japan: Archaeology and History of an Epochal Thousand Years, 400 B.C.–A.D. 600. Asian Perspectives, 46(2), 404-459. Retrieved June 18, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/42928724

Barnes, G. (2006). Women in the "Nihon Shoki" (4 parts). Durham East Asia Papers, No. 20.

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Lee, Jaehoon (2004). The Relatedness Between the Origin of Japanese and Korean Ethnicity. Florida State Univeristy Libraries, Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations. https://fsu.digital.flvc.org/islandora/object/fsu:181538/datastream/PDF/download/citation.pdf

Shultz, E. (2004). An Introduction to the "Samguk Sagi". Korean Studies, 28, 1-13. Retrieved April 11, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23720180

Iryŏn, ., Ha, T. H., & Mintz, G. K. (2004). Samguk yusa: Legends and history of the three kingdoms of ancient Korea. Seoul: Yonsei University Press.

Allen, C. (2003). Empress Jingū: a shamaness ruler in early Japan. Japan Forum, 15(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/0955580032000077748

Allen, C. T. (2003). Prince Misahun: Silla's Hostage to Wa from the Late Fourth Century. Korean Studies, 27(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1353/KS.2005.0002

Piggot, J. R. (1999). Chieftain Pairs and Corulers: Female Sovereignty in Early Japan. Women and Class in Japanese History. Edited by Hitomi Tonomura, Anne Walthall, and Wakita Haruko. Center for Japanese Studies, The University of Michigan. ISBN 1-929280-35-1.

Aoki, Michiko Yamaguchi (1997). Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki with Introduction and Commentaries. As published at https://jhti.berkeley.edu/texts19.htm

AKIMA, T. (1993). The Origins of the Grand Shrine of Ise and the Cult of the Sun Goddess Amaterasu Ōmikami. Japan Review, (4), 141-198. Retrieved December 25, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25790929

Ishino, H., & 石野博信. (1992). Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 19 (2/3), 191-216. Retrieved August 16, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/30234190

Naumann, Nelly (1992). ‘The “Kusanagi” Sword’. Nenrin-Jahresringe: Festgabe für Hans A. Dettmer. Ed. Klaus Müller. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1992. [158]–170. https://freidok.uni-freiburg.de/fedora/objects/freidok:4635/datastreams/FILE1/content

Edwards, W. (1983). Event and Process in the Founding of Japan: The Horserider Theory in Archeological Perspective. Journal of Japanese Studies, 9(2), 265-295. doi:10.2307/132294

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Bender, R. (1979). The Hachiman Cult and the Dōkyō Incident. Monumenta Nipponica, 34(2), 125-153. doi:10.2307/2384320

Hatada, T., & Morris, V. (1979). An Interpretation of the King Kwanggaet'o Inscription. Korean Studies, 3, 1-17. Retrieved June 18, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23717824

Shichirō, M., & Miller, R. (1979). The Inariyama Tumulus Sword Inscription. Journal of Japanese Studies, 5(2), 405-438. doi:10.2307/132104

Bender, R. (1978). Metamorphosis of a Deity. The Image of Hachiman in Yumi Yawata. Monumenta Nipponica, 33 (2), 165-178. doi:10.2307/2384124

Takeshi, M. (1978). Origin and Growth of the Worship of Amaterasu. Asian Folklore Studies, 37(1), 1-11. doi:10.2307/1177580

Ledyard, G. (1975). Galloping along with the Horseriders: Looking for the Founders of Japan. Journal of Japanese Studies, 1(2), 217-254. doi:10.2307/132125

Brazell, Karen (tr.) (1973). The Confessions of Lady Nijō. Stanford University Press. ISBN0-8047-0930-0.

Kiley, C. (1973). State and Dynasty in Archaic Yamato. The Journal of Asian Studies, 33(1), 25-49. https://doi.org/10.2307/2052884

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1

Hall, John W. (1966). Government and Local Power in Japan 500 to 1700: A Study Based on Bizen Province. Princeton University Press. ISBN978-0691030197