Previous Episodes

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we talk about the ascension of Ohodo, aka Keitai Tennō. That’s 「継体」, not 「携帯」. So why him, of all people?

Location, Location, Location

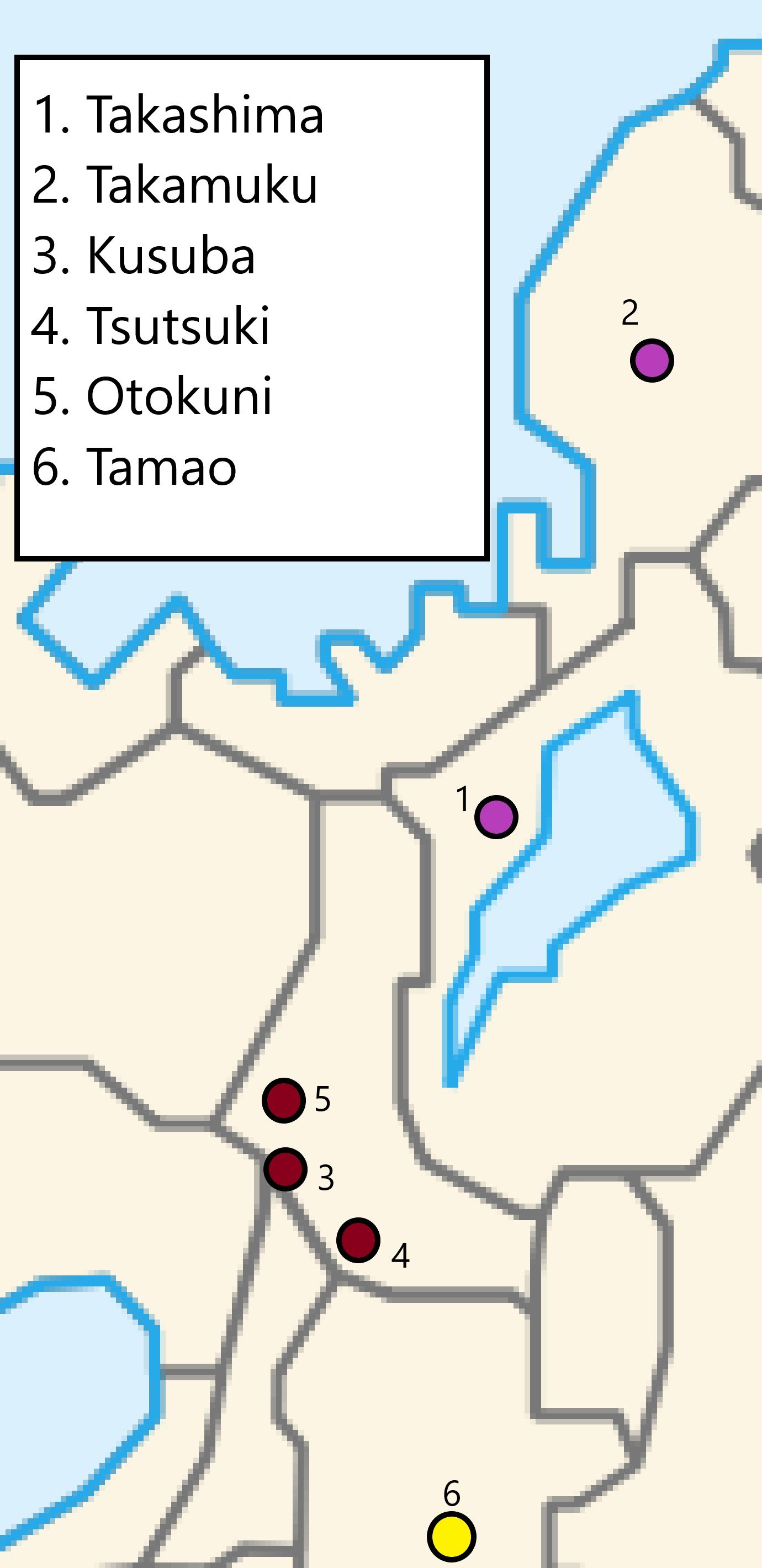

Before we get into the Who’s Who of this episode, let’s look at the locations we are talking about. Specifically, some of the locations regarding Ohodo, aka Keitai Tennō. First, there is Takashima (1), near Lake Biwa. This is where Wohodo’s dad is said to have lived, and where Ohodo was born, but when Ohodo’s father passed away, he and his mother went back to her hometown of Takamuku (2), in Mikuni. These are traditional locations, and not necessarily exact.

Once Ohodo ascended to the throne, his first palace is said to have been Kusuba (3), and then later he moved to Tsutsuki (4), and then Otokuni (5). First off, what is with all of this moving? Maybe the Nihon Shoki will give us some clues, but I’m not holding my breath. Second, why are they all outside the Nara Basin? They aren’t even in the Kawachi region. I guess one could argue that this indicates that Yamato’s influence had grown such that there were more places that could serve for the court, but that doesn’t quite sit right with me. Eventually, 20 years later, the did settle in Tamao (6), in Iware, just south of Mt. Miwa and the early seat of Yamato and just a bit northeast of the later Asuka courts and then the later Fujiwara Capital. Even his supposed kofun is located west of Kusuba, and on the other side of the Yodo River that flows from Biwa to the Seto Inland Sea at Naniwa.

Dramatis Personae

Ōtomo no Kanamura

Before we get into the sovereign, let’s briefly touch on Kanamura, likely son or descendant of Muruya. He appears to have been in charge of the court during Wakasazaki’s reign and now, here he is, choosing the next sovereign to sit on the throne. We unfortunately only know a little about him, but his actions speak volumes, in my opinion, and it will be something we see often enough. The service nobles of Yamato often realize they cannot make a direct claim to the throne, but yet it is through the throne that they earn their place. Thus, if you cannot sit on the throne, being the guy who puts people there is probably the next best thing—and possibly even a better thing, in a way, at least in later centuries. So just keep that in mind.

Tashiraga Ōiratsume

A sister to the late Ohatsuse Wakasazaki, the previous sovereign, and eventually the queen to the new sovereign, which will give her children a direct link to the previous dynasty through her, along with the connections brought to the table by her husband.

Ohodo

Prince Ohodo (or Wohodo) is, we are told, the newly chosen heir to the throne. But why? Well, it appears that his parentage connects him to both Homuda Wake and to Ikume Iribiko—a rather distinguished pedigree, assuming it is true. What follows is his presumed lineage.

Prince Ushi, aka Prince Hikonushi-bito and Hifuri Hime, aka Furu Hime

The parents to Ohodo. “Hikonushi” may come from “Hiko no Ushi”, and we’ve seen similar things elsewhere in the Chronicles, so it seems reasonable. “Hifuri” and “Furu” may have a bit more convoluted relationship, but nonetheless there are details that suggest they are the same person in different accounts.

We are told that Furu Hime’s lineage goes back to Ikume Iribiko, but I haven’t found it laid out in the same way as the paternal lineage. That said, it is an interesting claim, and one wonders if at some point the mother’s claim wasn’t as important—or possibly even moreso—than the father’s. After all, there is constantly a concern that the sovereign’s mother must have a royal lineage in order for their offspring to take the throne. The fact that it goes back to an even older dynasty makes me wonder.

Prince Oi

We aren’t given the wife of Prince Oi, only that he is the father of Prince Ushi, aka Hikonushi-bito.

Prince Ōhodo (or Oho-hodo)

We are told he was the father of Prince Oi, and again we are not given his wife. However, we are told that he was the brother of Oshizaka no Ō Naka tsu Hime, aka Osaka no Naka tsu Hime, wife of Oasatsuma Wakugo no Sukune, aka Ingyō Tennō. More on that, later. For now it is striking that Ōhodo’s name is so similar to Ohodo, seemingly indicating Hodo Sr. and Hodo Jr., though with several generations separating the two.

Waka Nuke (or Noke) Futamata and Momoshiko Mawaka Naka tsu Hime, aka Momoshiki Irobe

Futamata married Momoshiko (or Momoshiki) and gave birth to Prince Ōhodo and Princess Oshizaka. He appears in the Kojiki and the Nihon Shiki as a son of Homuda Wake, aka Ōjin Tennō. The Jōgūki lineage also says something similar, but instead of labeling Homutsu Wake as sovereign, or Ōkimi, it simply calls him another “Prince”. That certainly leaves us wondering if there was a mistake, or if all of the “Princes” here were perhaps of equivalent rank. Were they actually just another lineage of rulers elsewhere in the archipelago? Unfortunately, we don’t have much to go on.

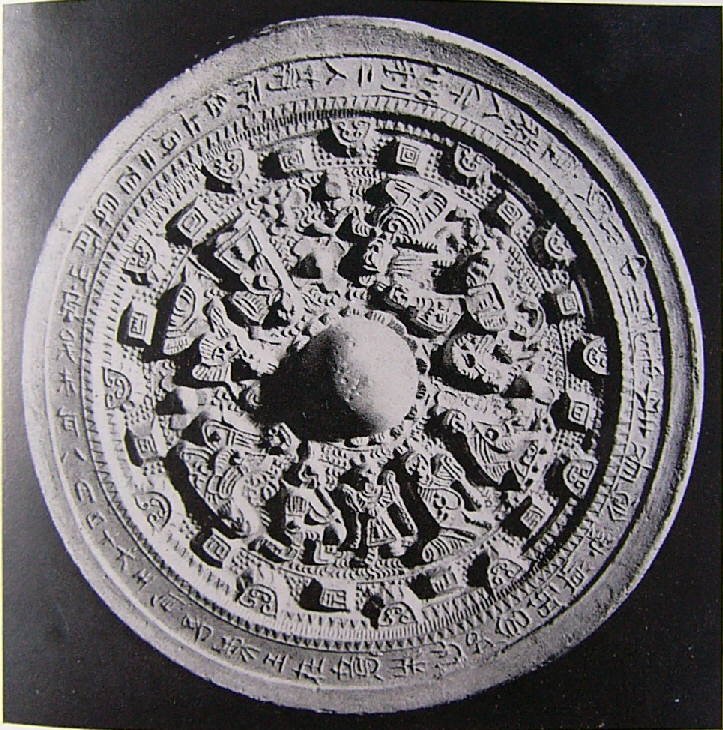

Ohodo’s lineage and the Suda Hachiman Shrine Mirror

There appear to be some clues to Ohodo’s lineage scattered in the inscription on the Suda Hachiman mirror, but the text is so vague that it can be read multiple ways. Some see it as celebrating a marriage between Oshizaka no Ō Naka tsu Hime and the sovereign, Ingyō Tennō. Others see a connection with either Ōhodo or Ohodo. The use of the sexegenary cycle for the year gives us some possibilities, but nothing solid, and 443 or 503 seem equally valid interpretations.

It may not give us concrete evidence, but just the same it does seem to give some legitimacy to these various names that we are encountering, whether or not they are actually involved in the lineage of our latest sovereign, Ohodo, I’m not sure I could say.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is Episode 75: The Mirror, Sword, and …Seal?

We are going to be talking about the person who followed Wakasazaki, aka Buretsu Tennou, known to us as Keitai Tennou—and no, that isn’t the Cell Phone sovereign, different kanji, despite the fact that it keeps coming to my mind. We’ll talk about what the Chronicles say about how he came to the throne, and what his lineage may have looked like. We’ll look at some of what we know around this period, and what some others have had to say. As usual, it is a bit difficult to say for certain what happened, but perhaps we can know a little bit.

Last episode we covered up to this point in the early 6th century, with the ongoing formation of the Yamato State. As we noted, although the Chronicles claim an unbroken lineage, there appear to have been at least two main dynasties, so far. The first was the Iribiko dynasty, starting with Mimaki Iribiko, who is credited as the founder of Yamato. Then there is the dynasty that tentatively begins with Okinaga Tarashi Hime and her son, Homtsu Wake—although possibly it actually starts with his son, Ohosazaki, for reasons we’ll talk about later. That second dynasty, which included the clearly historic figure of Ohohatsuse Wakatake, aka Wakatakiru no Ohokimi, or Yuryaku Tennou, ended around 506 with the death of Ohatsuse Wakasazaki—an aptly named bookend for the last descendant of Ohosazaki no Mikoto—the young Sazaki as the last heir to the Great Sazaki.

That dynasty seems plagued with succession disputes. Despite the order that the Chronicles attempt to apply to it, the remaining stories make many people suspect that after each sovereign’s death, there was a period of confusion and chaos. Different groups in Yamato and surrounding areas would often pick up arms and vie for power and control. Influential forces would rally around potential candidates—those with some claim to the throne. The Chronicles often makes the claim that they were direct descendants of a previous sovereign—sometimes even siblings to the sovereign who had just passed. It was clearly not a matter of strict patrilineal succession, however, and there are even more than a few women who may have thrown their hat into the ring, with Ihitoyo being one of the most convincing candidates so far.

During all of this, we see the rise of the various economic households. Most clearly are the Be—a continental innovation, where various individuals were gathered into a created household for economic purposes. Some of these are groups of similar professions. The Umakai-be, or the horsekeepers, and the Tamazukuri-Be, the Jewel-makers, are examples of these kinds of groups. Members were apparently scattered across various lands, but a single family remained nominally responsible for coordinating them. That family, sitting at the top of such a structure, would have had access to resources that that were produced by the other members, taking a bit off the top, as it were.

Other such families were dedicated to simply producing economic wealth, typically in the form of some number of koku of rice, for the upkeep of some person or institution. For instance, the upkeep of the monumental tombs that we see, or some particular family member.

We also see the service nobility—families who support the court and the sovereign and the business of the court, and through that maintain an elite status. Early on we see Takeuchi no Sukune and his descendants, who make up the Heguri, who are often the Ohomi, or Great Minister. Similarly there are the Mononobe, who appear to be a constructed -Be style family focusing on the arts of war—Mono-no-fu being another term for warriors—but who claim their own divine lineage through another Heavenly grandchild. Then there are the Ohotomo. They claim descent through Michi no Omi, or at least according to the Chronicles—Michi no Omi theoretically rode with the legendary Iware Biko, aka Jimmu Tennou, when he supposedly invaded Yamato. Later you see Ohotomo no Takemotsu serving in the time of Okinaga Tarashi Hime, aka Jinguu Tennou, and Ohotomo no Muruya, in the time of Wakatake no Ohokimi, aka Yuuryaku Tennou. This is probably the first reliable account of the Ohotomo family in the Chronicles as a powerful member of the court, but we will see their continued presence.

In the period of the second dynasty, the service nobility play a large role in running the state and even in helping to select new sovereigns. In the story recounting Wakasazaki, or Buretsu Tennou, Matori, of the Heguri family, appears to be the one in charge at the start, but Ohotomo no Kanamura, presumably the son or descendant of Ohotomo no Muruya, helps Wakasazaki overthrow and destroy Heguri no Matori, gaining his place as Ohomuraji in the process. In some ways, it seems as though the important political story of Wakaszaki’s reign at the turn of the 6th century wasn’t about him at all, but about the competition between the Heguri and the Ohotomo.

When Wakasazaki dies without an heir, it is these same service nobility who seem to be figured prominently in the next part of the story, the selection of the next sovereign.

According to the Chronicles, it was Ohotomo no Kanamura who made the pitch that they would need someone to sit on the throne. The Nihon Shoki puts this two weeks after the death of Wakasazaki, Kanamura proposed a candidate—one Yamato Hiko, a fifth generation descendant of Tarashi Nakatsu Hiko, aka Chuai Tennou. This Yamato Hiko was living in Kuhada, in the land of Tanba—modern Hyogo Prefecture.

The next part is a little, well, strange. Rather than sending a simple messenger to Yamato Hiko and asking him to come take the throne, they apparently sent what the Nihon Shoki refers to as an “honor guard”—so armed men. Now remember, up to this point, successions were a bloody affair, and when Yamato Hiko saw armed men coming for him, he took to the hills, not wanting to be purged just because he had a connection to an ancient sovereign. The men searched high and low but they could not find him.

And so, a few days later, Kanamura and the other nobles started the search anew. They focused on another prince, Prince Wohodo. The Nihon Shoki claims he was the son of another Prince, named Hiko Nushi-bito, and his wife, Furuhime. Although Hiko Nushi-bito lived in Miwo, in the district of Takashima—probably around the area of modern Takashima o nthe shores of Lake Biwa—Wohodo’s father passed away and his mother, Furuhime, took him back to her home of Takamuku. This was likely in the area of modern Fukui, in the old province of Echizen, the area of the ancient land of Koshi that was closest to the Kinai region. So that is where they sent the honor guard this time, to the land of Mikuni, to find Wohodo and ask him to take up the throne.

When the troops showed up this time, Wohodo remained calm, and sat there with his personal retainers. Still, he wasn’t exactly sure what was going on, and so he didn’t exactly consent, immediately. However, someone had snuck him a message beforehand to tell him what was going on. That was Kawachi no Umakahi no Obito no Arako, who let him know that this was a force coming to kill him, but rather to escort him back to the court. When everything was finally over, Arako would be well rewarded for his service.

Traveling with the honor guard, Wohodo made it down to the Kusuba palace, traditionally identified as being around Kuzuhaoka in Hirakata in modern Osaka. It was there that Ohotomo no Kanamura presented Wohodo with the Mirror, the sword, and the signet, or seal.

And let me take a moment and mark this occasion. We’ve seen discussions of the mirror and the sword before this point, and this seems to indicate the three items of imperial regalia of Japan: The Mirror, the Sword, and the Jewel. And this is the first time we’ve seen these used as part of the ascension ceremony, at least since they were first brought down to earth in the legend of the Heavenly Grandchild, Ninigi no Mikoto.

As you may recall, legends in the Chronicles claim that the Mirror and the Jewel were both hung on the Sakaki tree outside of the Heavenly Rock Cave as part of the ceremony to get Amaterasu to come out into the light. There is even mention of a blemish on the mirror from when it was accidentally knocked against the side of the cave. The sword implies the famous Kusanagi, or grass-cutter, found by Susanowo in the tail of Yamata no Orochi. Of course it could be that it was a different mirror and a different sword, but I think that any reader in the 8th century would have assumed these to be the same as those discussed earlier in the Chronicles. These were described back in episodes 15 and 16, as well as the descent of Ninigi no Mikoto in episode 22.

More reliably, it does seem there was a tradition in the archipelago of maintaining and even displaying elite goods, such as mirrors, jewels, and swords, from tree-like structures to announce or welcome royalty.

This is, however, the first time we’ve seen them brought out for an investiture—an enthronement ceremony—and you may have already caught on that there is one thing that is out of place. In the Nihon Shoki we are told that they used the mirror, the sword, and the… seal. Yeah, instead of the jewel—the Yasakani no magatama—we have a royal seal, instead.

Is this a seal received from one of the continental courts, confirming the sovereign of Yamato as the “King of Wa”? Or is it referencing the jewel, the magatama, but using a term that, in the classical language of the time, would have been expected in a continental enthronement ceremony?

Truth be told, the list of items included as required imperial regalia would vary over the years. Even by the 14th century the regalia was not necessarily firm, as pointed out by Thomas Conlan in his book, “From Sovereign to Symbol”, though the sword, mirror, and jewel do appear to be at the heart of it. In fact, Kitabatake Chikafusa, writing his national history, “Jinnou Shoutouki,” in the 14th century certainly identifies those three sacred objects as being at the heart of the institution of the sovereign and, by extension, the entire state. They are also mentioned in the Tale of Heike, where it is said that the Sacred Jewel and the Sword were taken up by Taira no Tokiko, widow of Kiyomori and grandmother to the infant Tennou, Antoku, as she leapt into the sea with him at the Battle of Dan-no-ura in the 12th century.

Now, just because we see these three regalia, don’t expect them to be coming up all the time from here on out. In fact, in 536 we will see only the sword and the mirror once more in the enthronement of the sovereign known as Senka Tennou, and then it seems to disappear from the narrative until the enthronement of the sovereign known as Jitou Tennou, wife of Temmu, in the 7th century, where again we get the sword, the mirror, and the seal.

In fact, the sword and mirror seem to be more constant than the jewel. In the 10th century Engi Shiki, or Procedures of the Engi Era, only the Sword and the Mirror are mentioned as part of the enthronement ceremony, or Daijousai. Herman Ooms, in his work in the Temmu Dynasty, “Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan,” suggests that the jewel was more of a private matter, passed within the house, perhaps even immediately upon a sovereign’s passing, while the sword and mirror were for public ceremonies. Whatever the case, it seems that in the Nihon Shoki, at least, the royal seal is more important. That fits with the general oeuvre of the genre, seeing as how they are doing their best to mimic the style of the continental chronicles, as well as continental systems of governance.

And so, Wohodo was raised up as sovereign, becoming the one who would later be called Keitai Tennou.

But who was this Wohodo, really? What do we know? What qualities did he possess that made him the rightful heir to the throne?

The Nihon Shoki’s explanation is somewhat lacking on this front. It is simply mentions that he was a descendant of Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, in the 6th generation, through his paternal line—his father being the 5th—but it also makes him an 8th generation descendant of Ikume Iribiko, along his maternal line, through Furu Hime. Effectively, they claimed that he was descended from both of the previous dynasties, giving further support to the theory that they are, indeed, separate.

The entry for Wohodo in the Kojiki isn’t much more help. It does give his descendants—and a brief mention of some conflict in Kyushu. However, there is an odd entry earlier, around the death of Homuda Wake. That covers the lineage of a seemingly unimportant son of Homuda Wake, named Waka Nuke Futamata. It is an odd entry, and might seem to just be lineages of various family lines, as he has a son, Oho-iratsuko, aka Oho-hodo no Miko—that is “Oho-hodo” as opposed to our current “Wo-hodo”, but if you see a connection, that does seem to be the intent. We are told he was an ancestor of, among others, the lords of Mikuni—Mikuni no Kimi. And of course, our current sovereign also has connections to Mikuni, according to the Nihon Shoki, though they say it is through his mother.

So even the Kojiki is a bit cagey on this subject, and it isn’t exactly a fully detailed lineage—there are plenty of gaps large enough that you could drive an ox-cart through. The Sendai Kuji Hongi doesn’t seem to be much better. It largely repeats the lineage given in the Nihon Shoki, without further details.

In fact, the most detailed lineage comes from somewhere else entirely—from a work called the Jouguuki, the biography of Prince Shotoku Taishi. This is thought to have been written around the 7th century, though unfortunately it only remains in fragments, such as in the Shaku Nihongi, which was written between 1274 and 1301 and contains fragments of many earlier works that are no longer extant as separate documents, including various fudoki, biographies, etc.

According to that biography, Wakanuke Futamata was the son of Homutsu Wake and Ote Hime Mawaka, the daughter of Kawamata Nakatsu Hiko. Futamata married Momoshiko Mawaka Nakatsu Hime—in the Kojiki we are told this is Momoshiki Irobe, aka Oto Hime Mawaka Hime no Mikoto. They had a son, Oho-hodo, again just like the the Kojiki. Ohohodo then had a son, Oi, who had a son, Ushi, who married one Hifuri Hime no Mikoto.

Prince Oi then becomes the connective tissue between Ohohodo in the Kojiki and the Nihon Shoki account, who has Hiko Nushi-bito marrying Furuhime. Assuming that Hiko Nushi Bito might be something like Hiko no Ushi Bito, and Furu Hime is the same as Hifuri Hime, this appears to line things up. They, of course, were the parents of Wohodo. Hifuri Hime’s lineage is also taken all the way back to Ikume Iribiko, as well, so that fits.

Of course, that doesn’t guarantee that any of this is true. After all, the compilers of the Nihon Shoki and the Kojiki may have been drawing from the Jouguuki, or vice versa, and if any part of that lineage was constructed wholecloth then it brings everything into question.

Kitabatake Chikafusa, in his writings, even suggested that Wohodo was descended from Ōsazaki’s rival, Hayabusa Wake. Then again, he could just be misremembering, as it is said his work was written without access to the source material, while he was in exile. Nonetheless, an interesting takeaway.

The various lineages of Wohodo do seem to acknowledge two dynasties, however, and I can’t help but wonder how much these biographies were projected back in time. Perhaps it is because of Mimaki Iribiko and Ikume Iribiko’s connection to Wohodo that we see stories about them, rather than about Himiko or Toyo, or others. After all, it is from Wohodo forward that we get the current lineage, and it should be noted that rarely do the Chronicles actually name the sovereign in their reign—the statements are simply that the ruler did this or the sovereign did that. So it would be easy enough to replace one sovereign with another to keep the biographers happy.

Some, such as Russell Kirkland (Kirkland, R. (1997). The Sun and the Throne. The Origins of the Royal Descent Myth in Ancient Japan. Numen, 44(2), 109–152. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3270296) have suggested that it was from about this same period that many of the founding myths about the kami would havearisen. In particular he suggested that myths of heavenly descent from Takami Musubi probably originated around this time, followed by the introduction of Ōhirume as a sun goddess in the late 6th century, with Amaterasu herself not taking center stage until about the 7th century. Either way, it is likely that many legends and content of earlier chapters was at least massaged to better support the current dynasty, which claims decent through Wohodo.

I also wonder if Wohodo’s connection to two dynasties doesn’t indicate something about the co-rulership theory. Were they trying to bring two lines of co-rulers into a single entity in Wohodo? After all, from here on out, it looks like Kishimoto’s theory simplifies down to a single sovereign. In all there are a lot of questions, and unfortunately very few answers. We could go back and forth about all of the things it *could* indicate, and there are literally shelves and shelves of books written on the topic.

There is one curious thing that is probably worth mentioning, however, and that is a bit of evidence from outside of the Chronicles. It is an inscription, found on a bronze mirror. This mirror is a treasure of the Suda Hachiman Shrine, in modern Wakayama Prefecture, in the Suda district of Hashimoto city, on the Kii peninsula, south of the Nara Basin, though it is now kept at the Tokyo National Museum.

The mirror has a rather intricate back, with various figures displayed around it, but it is most notable for the inscription along its rim. The inscription is clear enough, but unfortunately not great. Besides numerous grammatical errors—from using the wrong characters to some characters even being reversed, which was apparently not that uncommon given how mirrors were cast for production. Then there are some characters that are out of order, all of this suggesting that this was not a native speaker but someone from another language group trying to write in Han characters.

David Lurie, in his article on the Suda Hachiman Shrine Mirror, gives a possible translation of the transcription as follows:

“On the tenth day of the eighth month of the twentieth year of the cycle”, Here Lurie suggests the year 503, though 443 has also been proposed by others, “during the reign of the Great King, when his younger brother the prince resided in Oshisaka Palace, Shima thought to serve him for a long time, and had Kawachi no Atai and Ayahito Imasuri, the two of them, take two hundred-weight of white bronze and make this mirror.”

Other than the inscription, the mirror appears to be from the same mold, or a copy of the same mold, as various other mirrors found in the archipelago, copying mirrors from the continent. That there is writing tells us that someone involved with the production knew how to write—and presumably read—though there are also an inner series of graph-like markings that appear to be a kind of pseudo-inscription: an imitation of writing but without any actual meaning. Personally, I wonder if that just wasn’t part of the mold that they used as a basis to create the mirror in the first place.

The inscription seems to give us several things. First of all, there is mention of the Oshizaka Palace. Princess Oshizaka no Ohonakatsu Hime, aka Osaka no Nakatsu Hime, is said to have been sister to Prince Oho-hodo, our current subject’s supposed great-grandfather, and we are told that she married Oasatsuma Wakugo, aka Ingyou Tennou. If that is true, perhaps we are seeing some mention of their relationship.

Other readings have suggested the name Ohodo or Oho-hodo as well, possibly indicating either the current sovereign or his great-grandfather. There are even suggestions that the “Shima” here is the Baekje King, Muryeong, and that perhaps there is even a peninsular connection—and there are certainly quite a few entries about Baekje in this reign. Either way, there seems to be some historical evidence surrounding bits of what we are finding in the Chronicles, but nothing links up quite as nicely as we would like for it to do so. Sometimes this stuff is like a giant jigsaw puzzle, except that half the pieces are missing, and some number of the ones that are left are from a different box entirely. The Chroniclers’ answer was to do the best they could, even if that meant redrawing the pieces, or cutting them so they would fit together better, and the picture on the box is completely different than the pieces you have.

Clearly, though, Wohodo was being brought in from outside, and starting a new line. Whether or not this lineage is a fabrication to justify his rule, or perhaps the Chronicles themselves are a projection of his own lineage back into the ancient stories, he was the one placed on the throne. And the person doing that appears to be none other than Ohotomo Kanamura.

And here is where I suspect that Kanamura may have been the architect behind a lot of this. After all, he is the one that “finds” Wohodo. He had been politically ascendant during the reign of Wakasazaki, aka Buretsu Tennou, and now here he is selecting the next sovereign. Once he brings Wohodo in, the next step is that he has Wohodo marry Tashiraga no Iratsume, one of Wakasazaki’s sister. So now we have an heir with claims to Homuda Wake and Ikume Iribiko, and, through this marriage, we have a direct continuation of the previous lineage, though as we’ll see, that may take a few tries before it comes to fruition.

There are still questions about how this all came to be. Was it really a peaceful transition of power? Or was this another series of bloody wars and invasions? A few things to note suggesting that things are up.

First, although Wohodo is made sovereign in 507, there is a note in 511 that the “capital was transferred to Tsutsuki, in Yamashiro,” traditionally located north of Nara in modern Kyotanbe. Then, in 518, the capital moved to Otokuni, also in Yamashiro—in modern Muko city, just southwest of Kyoto. Finally, in 526, it moved to Tamao, in Iware.

So Wohodo gets selected as the new sovereign of Yamato, but then for about twenty years he is living outside of the Nara Basin, in areas not traditionally associated with the capital of Yamato. So what was going on for those first twenty or so years? Was there conflict? Was there something else going on in the Nara Basin?

Unfortunately, the Nihon Shoki glosses over any conflict and presents a picture of unified support of the new sovereign. Yet I doubt that a new sovereign could just be brought in and be immediately acclaimed by all. Rather, it all seems to have been orchestrated by Ohotomo Kanamura and his allies at court, and that may have been much more contentious than is depicted.

In the end, we are left with what we have. We are told that Wohodo accepted the throne, and was invested with the mirror, sword, and the official seal. He took to wife Tashiraga Hime, and thus he became the next sovereign. In the next episode we can cover what the Chronicles say about his reign.

Until then, thank you for listening and for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com. It is always great to hear from people and ideas for the show.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Barnes, Gina L. (2015). Achaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilization in China, Korea and Japan

Barnes, G. (2014). A Hypothesis for Early Kofun Rulership. Japan Review, (27), 3-29. Retrieved March 12, 2020, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/23849568

Kishimoto, Naofumi (2013). Dual Kingship in the Kofun Period as Seen from the Keyhole Tombs. UrbanScope: e-Journal of the Urban-Culture Research Center, OCU. http://urbanscope.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/journal/pdf/vol004/01-kishimoto.pdf

Conlan, Thomas (2011). From Sovereign to Symbol: An Age of Ritual Determinism in Fourteenth-Century Japan. ISBN 978-0199778102.

Como, Michael (2009). Weaving and Binding: Immigrant Gods and Female Immortals in Ancient Japan. ISBN978-0-8248-2957-5

Lurie, D. B. (2009). The Suda Hachiman Shrine Mirror and Its Inscription. Impressions, 30, 27–31. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42597980

Ooms, Herman (2009). Imperial Politics and Symbolics in Ancient Japan: The Tenmu Dynasty, 650-800. ISBN978-0-8248-3235-3

Kawagoe, Aileen (2009). “Uji clans, titles and the organization of production and trade”. Heritage of Japan. https://heritageofjapan.wordpress.com/following-the-trail-of-tumuli/rebellion-in-kyushu-and-the-rise-of-royal-estates/uji-clans-titles-and-the-organization-of-production-and-trade/. Retrieved 1/11/2021.

Soumaré, Massimo (2007); Japan in Five Ancient Chinese Chronicles: Wo, the Land of Yamatai, and Queen Himiko. ISBN: 978-4-902075-22-9

Bentley, J. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from https://brill.com/view/title/12964

Varley, Paul H. (trans.) (1980). A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns; Jinno Shotoki of Kitabatake Chikafusa.

Piggott, J. (1997). The Emergence of Japance Kingship

Kirkland, R. (1997). The Sun and the Throne. The Origins of the Royal Descent Myth in Ancient Japan. Numen, 44(2), 109–152. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3270296

Kiley, C. J. (1973). State and Dynasty in Archaic Yamato. The Journal of Asian Studies, 33(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/2052884

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1