Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we start our look at the reign of Ame Kunioshi Hiraki Niha, aka Kinmei Tennō. We’ll start off with a look at his ascension to the throne and some of the politics that we can see going on in the court. We’ll also discuss some of the theories regarding this reign, particularly its chronological placement in the Chronicles, which may not be exactly as it seems. Still, we are in what many consider to be the historical period, meaning that the records the Chroniclers were working from are assumed to be more accurate—they were likely using more written material, including books we no longer have extant. However, that doesn’t mean everything is factual, and it is clear there are still some lacunae in the texts and some additional massaging by the Chroniclers themselves.

Dramatis Personae

Magari no Ohine, aka Ankan Tennō - Eldest son of their father, Wohodo no Ōkimi, aka Keitai Tennō. His rule was short, but there were still a few things to note.

Takewo Hiro Kunioshi Tate, aka Senka Tennō - Full brother to Magari no Ohine, he was their father’s second eldest, and he succeeded his brother to the throne.

Ame Kunioshi Hiraki Niha, aka Kinmei Tennō - Son of Wohodo no Ōkimi and his queen, Tashiraga—or at least that is what the Chronicles tell us. He was one of the youngest sons of Wohodo, and probably came to the throne in his 20s or 30s. He is our current sovereign this episode—and for a few episodes to come.

Kasuga no Yamada no Himemiko - Wife to Magari no Ohine, she could have possibly taken the throne, but she deferred to Ame Kunioshi—or so we are told. She appears to be part of the Kasuga family.

Ōtomo no Kanamura no Ōmuraji - Long time minister of Yamato, Kanamura has built a successful career through two dynasties, often with a focus on his exploits on the continent. However, by this reign he is old, and it is unclear that his sons will be able to maintain the family’s position of prominence.

Mononobe no Okoshi no Ōmuraji - Successor to Arakahi, the Mononobe have an illustrious history, going back to the earliest sovereigns. They are quite involved both in the archipelago and on the peninsula at this point. There are numerous individuals using the Mononobe family name on the continent who end up with Baekje titles, rather than Yamato ones.

Soga no Iname no Sukune no Ōmi - For anyone reading ahead, you know where this is going. Soga no Iname is the first Soga to achieve the rank of Ōmi. The fact that he has a personal rank of Sukune is not insignificant, either, though it is unclear when he actually achieved that—there is a tendancy in the Chronicles to use the last title a person had when talking about them. Still, there is little doubt that he will feature prominently in stories to come.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is episode 81, the Politics of the Early Yamato Court.

Last episode, before our Nara tour interlude, we covered the life of Takewo Hiro Kunioshi Tate, aka Senka Tennō. He picked up where his brother, Magari no Ohine, aka Ankan Tennō, had[EB1] left off, and is said to have reigned for about two and a half years, from 536 to 539. During that time we see more of the rise of the family of Soga no Omi but we also see the Ōtomo no Muraji and the Mononobe going quite strong. The sons of Ōtomo no Kanamura ended up involved with the government in Tsukushi, aka Kyuushuu, as well as the war efforts across the straits, mainly focused on Nimna and the surrounding areas. Indeed, as we talked about last episode—episode 80—it is said that Ohtomo no Sadehiko went to Nimna and restored peace there, before lending aid to Baekje[EB2] .

This preoccupation with Nimna and events on the Korean peninsula are going to dominate our narrative moving forward, at least initially. Much of the next reign focuses on events on the peninsula, rather than on the archipelago. Oddly, this preoccupation isn’t d everywhere. In the Sendai Kuji Hongi—and other copies of the same work—there appears only a brief mention of Nimna, aka Mimana, in the record, which otherwise simply talks about inheritance and similar issues.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Before we dive into all of that, to include all of the peninsular goodness that we have coming our way, let’s briefly talk about some of the things a little closer to home. Mainly, let’s talk about the succession and who our next sovereign appears to be.

So first off, his name is given as Ame Kunioshi Hiraki Hiro Niha, and he is posthumously known to us as Kimmei Tennō. For my part, rather than repeating the whole thing, I’m going to refer to him simply as Ame Kunioshi, though I’m honestly not sure if the best way to parse his name, assuming it isn't just another type of royal title. He is said to have been the son of Wohodo no Ōkimi, aka Keitai Tennō, and his queen, Tashiraga, a sister to Wohatsuse Wakasazaki, aka Buretsu Tennō. This would all seem pretty straightforward if it weren’t for the fact that two of his half-brothers had taken the throne before him. Prince Magari and his brother, Takewo, were descended through another line, that of Menoko, daughter of Owari no Muraji no Kusaka. Menoko did not appear to meet the Nihon Shoki’s Chroniclers’ strict requirements for being named queen—namely, they don’t bother to trace her lineage back to the royal line in some way, shape, or form. As such, the Nihon Shoki tries to pass off the reigns of the two brothers as though they were just keeping the seat warm while Ame Kunioshi himself came of age.

None of the language used, however, really suggests that they were not considered legitimate in the eyes of their respective courts, and in all aspects they played the part of sovereign, and it is quite likely that if they had reigned long enough, or had valid heirs, themselves, we may be reading a slightly different story. As it is, the Chroniclers likely manipulated the narrative just enough to ensure that things made sense in terms of a linear progression.

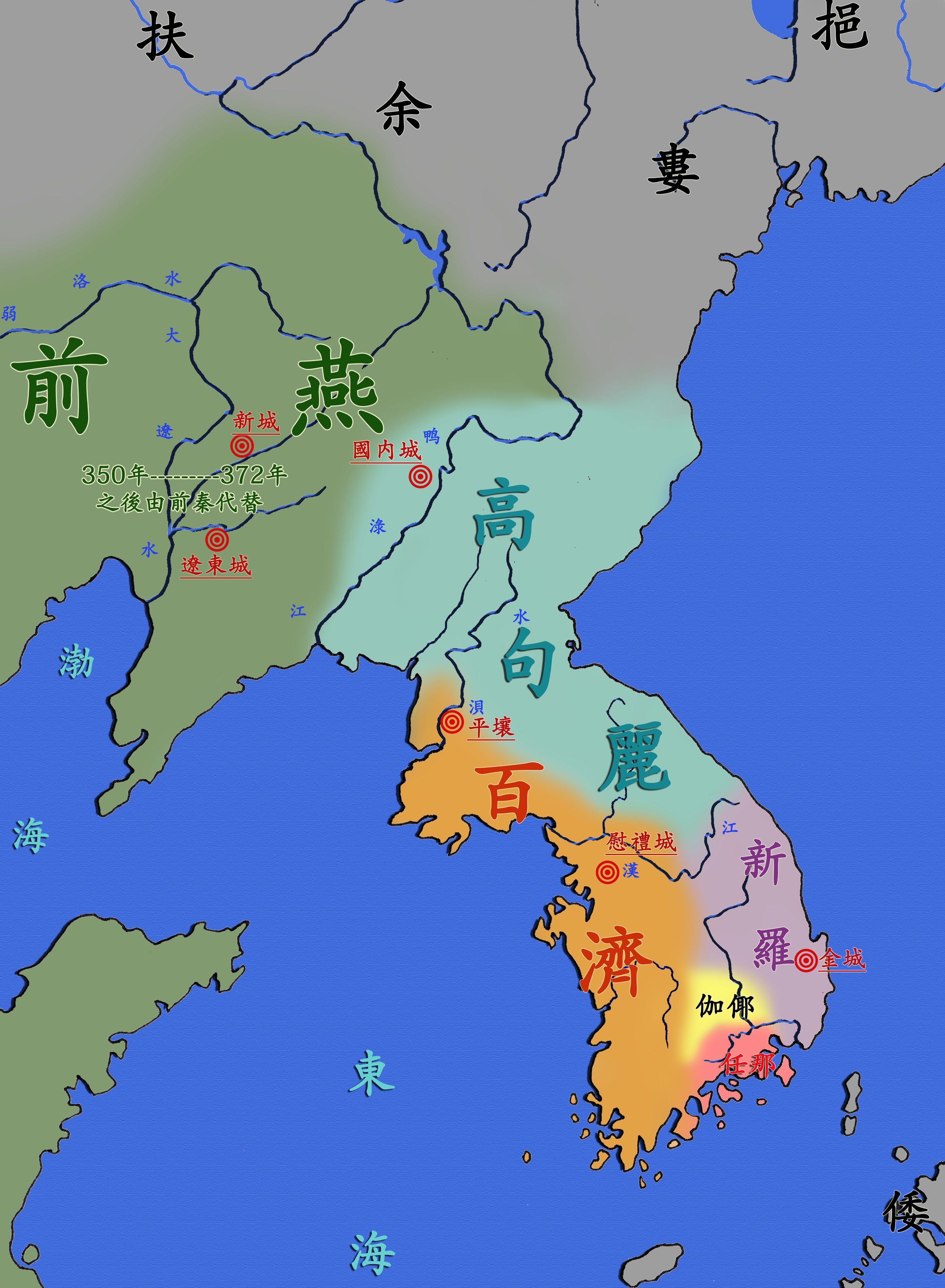

And that manipulation hardly stopped at his ascension. The account of Ame Kunioshi on the throne is filled with questionable narration. Beyond just the fantastical—accounts of kami and of evil spirits—much of the reign is focused on events on the Korean peninsula, and these are almost always portrayed as actions by the Kingdom of Baekje, one of the three largest kingdoms across the straits, along with Silla and Goguryeo. Baekje, in turn, is portrayed in the Nihon Shoki as a loyal vassal state, constantly looking to the sovereign of Yamato as their liege and attempting to carry out their will.

For the most part, this is a blatant attempt by the Chroniclers to place Yamato front and center, and in control of events on the mainland. Taken at face value, it has for a long time fueled nationalist claims to the Korean peninsula, and may have even been designed for that very purpose. Remember, a history like this was written as much for a political purpose as it was record for posterity, and the narration is about as trustworthy as that of a certain fictional radio host in a sleepy desert community.

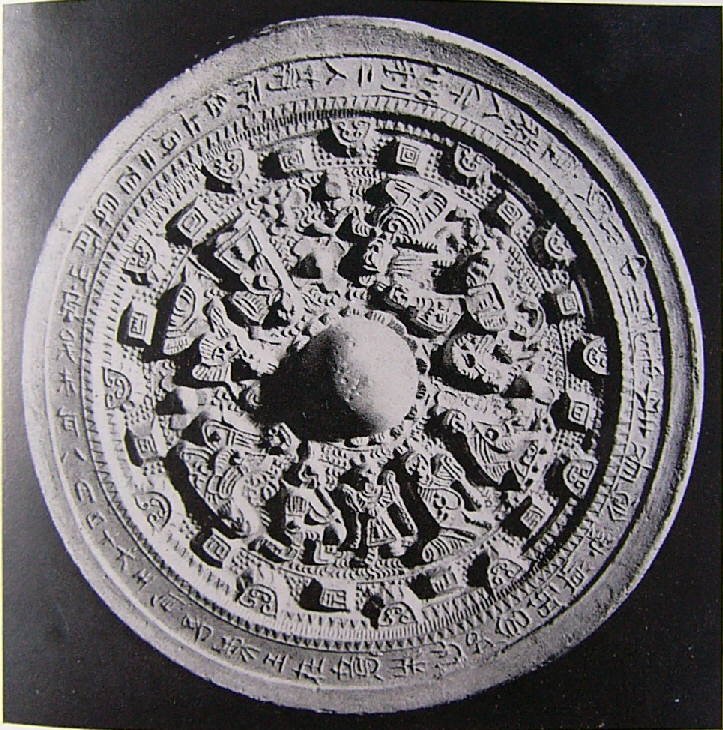

And yet, we want to be careful about throwing the proverbial baby out with the bathwater, here. The Nihon Shoki is a treasure trove of stories about this period and what was happening on the mainland, even if we have to be careful of taking everything at face value. The details given in the text are sometimes more than any other sources we have for this period, and they are certainly closer to the source. Korean sources, such as the Samguk Sagi, the Samguk Yusa, and the Tongkam all have their own gaps in the literature of the time, as well as their own political aims and goals, such that even they are suspect. Sure, the flowery speechification is probably a little too much, but much of the back and forth seems reasonable, and there are numerous times where the Nihon Shoki directly quotes the copy of the Baekje annals that they had at the time—a text that is no longer extant, and which seems to have items that did not make it into later collections. By following the back and forth and the flow of allegiances and deceptions, and looking at who was said to have been involved—both the individuals and the countries—we might be able to draw a picture of this era.

And what a picture it will be. I probably won’t get to it all today, but there is conflict over Nimna, with Baekje and Yamato typically teaming up against Silla and Goguryeo, but there are other things as well. For one thing, nothing in this era is cut and dried, and while there are overarching themes, alliances were clearly fluid, and could quickly change. Furthermore, all this activity spawned a new level of interaction, particularly between Baekje and Yamato, and we see a new era of Baekje sharing their knowledge with Yamato. For instance, this reign we see the first mention of Yin-Yang Divination studies—the famous Onmyouji—as well as calendrical studies in the archipelago. We also see the arrival of Buddhism to the islands. Well, at least we see the formal introduction of Buddhism; given all of the people in the archipelago who came over from the continent, there were likely more than a few Buddhists already living in the archipelago, but it hadn’t grown, yet, to be a State religion, as it would be in later centuries.

To try to do this period justice, I’m going to try to break things down a bit so that we can focus on various themes as we move through the stories here. It will probably take us a few episodes to get through. Furthermore, at some point here I want to talk about this new religion, Buddhism, and how it traveled all the way from India to the islands of Japan. But for now, let’s focus on the Chronicles.

Not all of what is talked about in this reign is focused on the mainland, so I’m going to start us off talking about the stories about this period that are taking place in the islands themselves, starting with how Ame Kunioshi came to the throne. Or rather, with some events just before he came to the throne.

The first story about Ame Kunioshi comes when he is simply a prince—it is unclear during which reign this is supposed to have happened, only that it happened before he came to the throne. The Chronicles say that Ame Kunioshi had a dream in which he was told to seek out a man named Hata no Ōtsuchi.

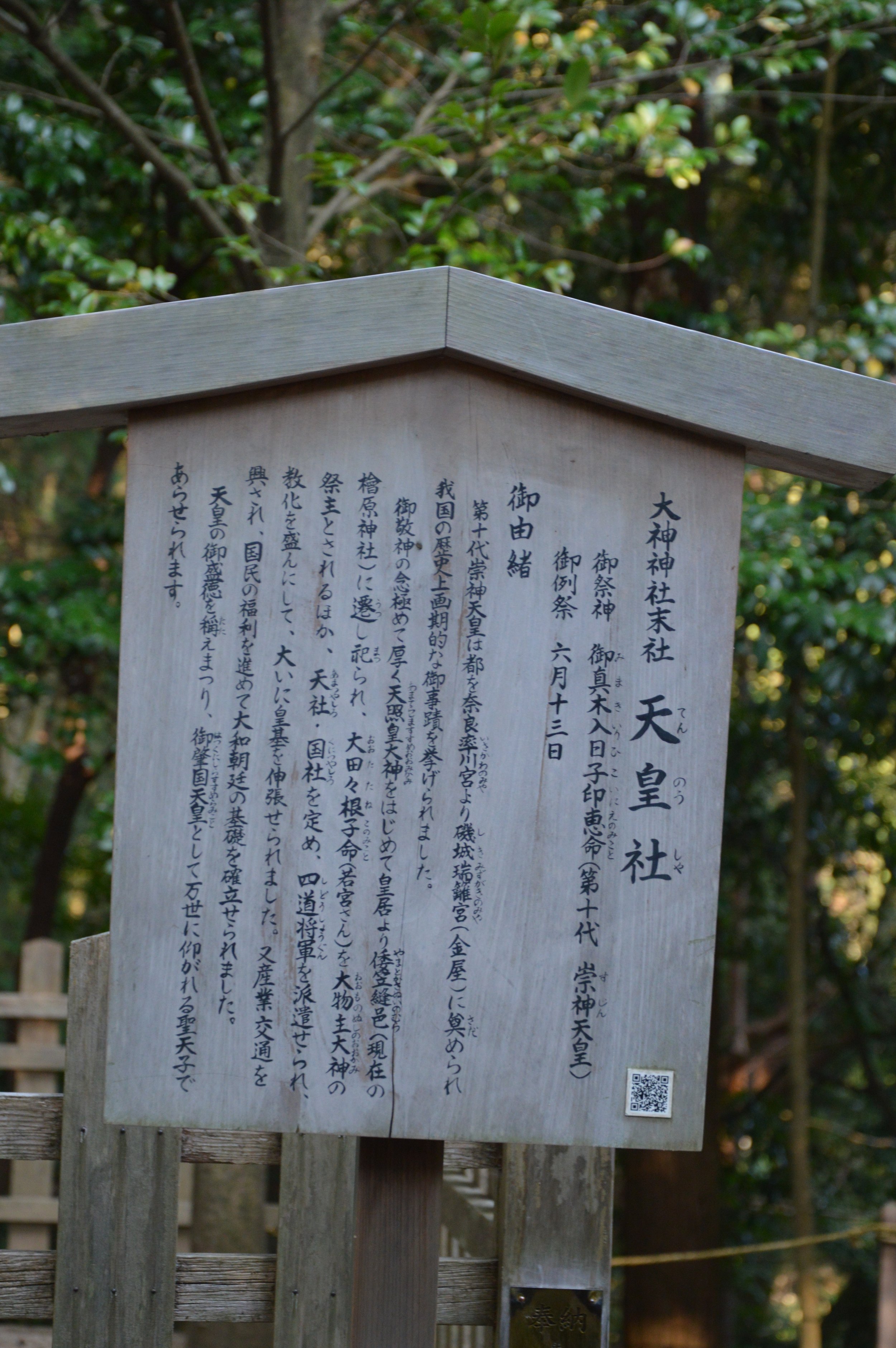

We’ve seen in the past these kinds of oracular dreams, where the gods, or kami, will speak directly to a person—often to the sovereign or someone close to the sovereign. By all accounts, the ability to act as a conduit for the kami was an important aspect of rulership and political power at this time, and we’ve seen the supposed consequences of not listening to such an oracle as well. And so he sent people out to find this man, who was eventually found in the Kii district of the land of Yamashiro.

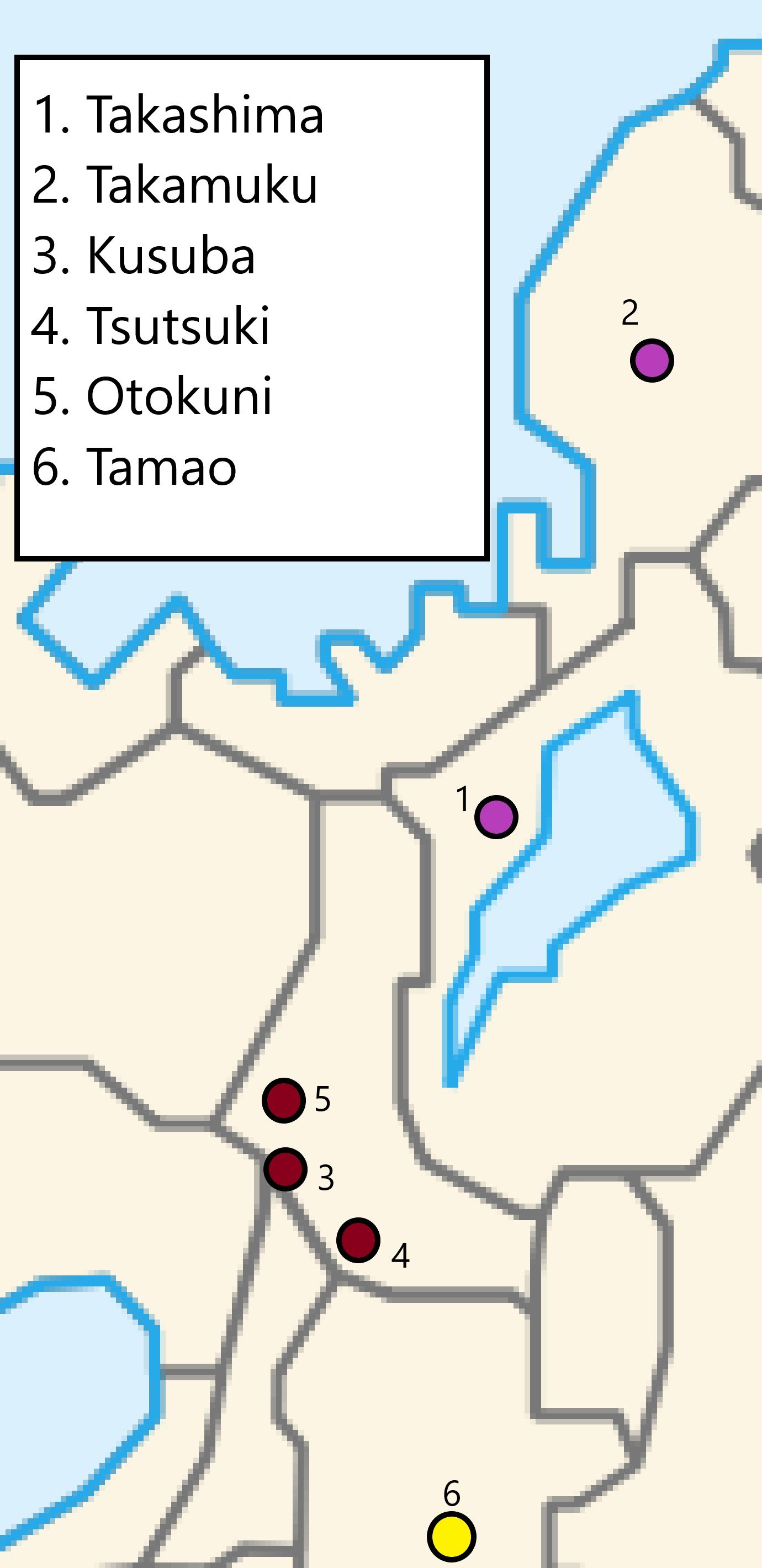

Now this area is not surprising. It is identified as the area, today, in the modern Fushimi district of Kyoto. In fact, it includes the area of the famous Fushimi Inari Taisha—the Fushimi Inari shrine. That shrine is also connected to the Hata family.

For those who don’t recall, the Hata family appear to have been descended from weavers who were brought over from the continent. The kanji used for their name is the same as that of the Qin dynasty, from which we get the modern name of China, though the pronunciation is taken from the word “Hata”, which appears to refer to a type of cloth, and also resembles the word for banners or flags. We mentioned them some time back in episode 63, when we talked about one of the early heads of the Hata, who was given the name Uzumasa. That name is still used to identify a district in Kyoto to this day.

And so here we are, back in the Kyoto area, near Fushimi shrine, which is also, as it happens, connected to the Hata family. That story is found not in the Nihon Shoki, but rather it is attributed to fragments of the Yamashiro no Fudoki. In that account we hear tell of a wealthy man named Irogu, whom we are told is a distant relative of Hata no Nakatsu no Imiki—no doubt a contemporary to the Yamashiro Fudoki, and the reason the story made the cut. Irogu, it seems, had made himself wealthy through rice cultivation. In fact, he had so much rice that he was using mochi—pounded glutinous rice cakes—as targets for his archery practice. As he was shooting at the mochi, suddenly one of them turned into a swan and flew up into the sky, up to the top of a nearby mountain. Where it landed rice, or “ine”, began to grow.

That mountain is none other than the site of Fushimi Inari Shrine, a shrine that will show up again and again in various stories, as it was quite prominent. Though the shrine was only founded in the 8th century, the story may indicate that there were older rituals, or perhaps that it was a focus of worship much like Mt. Miwa, down in the land of Yamato, to the south, and that shrine buildings were simply added to the mountain at a later date. Fushimi is, of course, the place, and Inari is the name of the god, or kami, worshipped at the shrine. Inari is a god of farming—specifically of rice cultivation—and today small Inari shrines can be found throughout Japan. They are typified by red gates—usually multiple gates, one after the other, often donated by various individuals. In addition, one might see Inari’s servants and messengers, foxes, which take the place of the lion-dogs that often guard shrine precincts. Importantly, these foxes are not the kami themselves, but simply the kami’s messengers. Still people will often bring gifts of oily, deep fried tofu—abura-age—said to be a favorite of foxes, to help ensure that their prayers—their messages to the kami—are swiftly and properly delivered.

I could probably do an entire episode on Fushimi Inari and Inari worship in Japan. There is so much material on the phenomenon on foxes, or kitsune, and fox-spirits, especially with the co-mingling of both continental and insular belief, which is sometimes at odds. For now, however, we can confine ourselves to the fact that Fushimi clearly had connections to the Hata family, who have shown up a few times in the past, but are still largely taking bit roles in things at the moment. Nonetheless, since the Chroniclers were writing from the 8th century, things like this, which were no doubt important to the powerful families of their day, were often included.

Getting back to our main story, when Hata no Ōtsuchi came before the prince, Ame Kunioshi, he told a story of how he had been traveling the land, coming back from trading in Ise, when he came upon two wolves, fighting each other on a mountain. The wolves were each covered in blood from their hostilities, and yet, through all of that, Hata no Ōtsuchi recognized them as visible incarnations of kami. Immediately he got off his horse, rinsed his hands and mouth to purify himself, and then made a prayer to the kami. In his prayer he admonished them for delighting in violence. After all, while they were there, attacking each other, what if a hunter came along and, not recognizing their divine nature, took both of them? With his earnest prayer he got them to stop fighting and he then cleaned off the blood and let them both go, thus saving their lives.

Hearing such a story, Ame Kunioshi determined that his dream was likely sent by the same kami saved by Ōtsuchi, or perhaps another spirit who had seen his good deed, who was recommending this good Samaritan to the prince. And who was he to deny the kami? So when he came to the throne, Ame Kunioshi put Hata no Ōtsuchi in charge of the Treasury.

That would have to wait until he actually ascended the throne, however; an opportunity that preserved itself with the death of his half brother, Takewo no Ōkimi. When Takewo passed away in 539, we are told that the ministers all requested that Ane Kunioshi take the throne, but at first he deferred, suggesting that the wife of his eldest half brother, Magari no Ohine, aka Ankan Tennō, take the throne, instead.

This was the former queen, Yamada, daughter of Ōke no Ōkimi, aka Ninken Tennō, so no doubt she had a good sense of how the government should work. Yet she, too, waved off the honor. Her reasoning, though, is a very patriarchal and misogynistic diatribe about how women aren't fit four the duties of running the country. Clearly it is drawn from continental sources, and it always makes me wonder. After all, the Nihon Shoki was being written in the time of rather powerful women controlling the Yamato court – which, I imagine irked some people to no end, especially those learned in classic literature, such as the works of Confucius.

So I wonder why this was put in. Did he truly defer to her? Or was this just to demonstrate his magnanimous nature? Was she pushed aside by the politics of the court? I also wonder why they went to her, and not Takewo’s wife. It is also interesting to me that the Chroniclers only note her own objections to her rule, and there isn't a peep out of the assembled ministers.

There appears to be another possible angle. Some scholars have pointed out inconsistencies with the timeline and events in the reign of Ame Kunioshi that may have actually happened much earlier, including the arrival of Buddhism. They suggest that perhaps there was a period of multiple rulers, possibly rival dynasties, with Magari no Ohine and his brother, Takewo, handling one court and Ame Kunioshi ruling another. If that were the case, then was Yamada the senior person in the other line? At the very least she represents the transfer of power and authority over to Tashiraga’s lineage.

Moving forward, we’re going to want to pay close attention to these kinds of political details. Often we’ll see how how princes of different mothers will end up as pawns in the factional infighting that will become de rigeur in the Yamato court, with different families providing wives in the hopes that they might eventually be family members to the next sovereign.

So, however it really happened, Ame Kunioshi took the throne. He reappointed Ōtomo no Kanamura and Mononobe no Okoshi Ōmuraji and named Soga no Iname no Sukune back to his position as Ō-omi. He set up his palace at a place called Shikishima, in the district of Shiki in the middle of the Nara Basin in the ancient country of Nara—still within sight of Mt. Miwa and, by now, numerous kofun built for previous kings, queens, and various nobles. Both the Emishi and the Hayato are said to have come and paid tribute—apparently part of the enthronement rituals—and even envoys from Baekje, Silla, Goguryeo and Nimna are said to have stopped in with congratulatory messages. These were probably fairly pro forma messages to maintain good—or at least tolerable—relations between the various states of the day, not unlike today when various people call a newly elected president or prime minister to congratulate them on their own entry to office.

He also took as his Queen his own niece, daughter of his half-brother, the previous sovereign, Takewo Hiro Kunioshi Tate, aka Senka Tennō. Her name was Ishihime, and she would provide Ame Kunioshi with several children, including the Crown Prince, Wosada Nunakara Futodamashiki no Mikoto, aka the eventual Bidatsu Tennō.

By the way, for anyone concerned that Ame Kunioshi was” robbing the cradle”, so to speak, remember that he was already 33 years younger than his brother. It is quite possible, assuming the dates are correct, that he and Ishihime were roughly the same age. To put it another way, if Ame Kunioshi was a Millennial, his brother Takewo had been a Boomer, meaning that Ishihime was likely either Gen X or a Millennial herself, to extend the analogy.

Of course, they were still uncle and niece, so… yeah, there’s that. I could point out again that at this time it was the maternal lineage that determined whether people were considered closely related or not. Children of different mothers, even with the same fathers, were considered distant enough that it was not at all scandalous for them to be married, and that we probably should be careful about placing our own cultural biases on a foreign culture—and at this point in history many aspects of the culture would be foreign even to modern Japanese, just as a modern person from London would likely find conditions in the Anglo Saxon era Lundenwic perhaps a bit off-putting. Still, I don’t think I can actually recommend the practice.

Now it is true he was coming to the throne at relatively young age. He was probably about 30 years old when he took charge of the state, while his brothers, their father’s eldest sons, had come to the throne much later in life, in their 50s or 60s. And if Ame Kunioshi was actually ruling earlier then he might have been younger, running the state of Yamato—or at least some part of it—when he was still in his early 20s.

Along with Ishihime, Ame Kunioshi took several other wives. The first two were Ishihime’s younger sisters, Kurawakaya Hime and Hikage. Then there were two daughters of Soga no Iname—and yes, *that* Soga no Iname, the re-appointed Ō-omi. At least three of the next four sovereigns would come from those two unions, and I’ll let you take a guess at how the Soga family’s fortunes fared during that time.

Finally, the last wife was was named Nukako, and she was the daughter of Kasuga no Hifuri no Omi.

Kasuga was also the family name of Kasuga no Yamada no Himemiko, who had turned down the throne to allow Ame Kunioshi to ascend, though we don’t hear too much else from the Kasuga family. This could be connected to that, although it is hard to be certain. For the most part the Kasuga family seems to stay behind the scenes, but the fact that they are inserting themselves into the royal line at different points would seem to be significant.

The Soga, on the other hand, are going to feature quite prominently in matters of state moving forward.

While it is unclear just when the various marriages occurred—they may have happened before or after his ascension to the throne—it is interesting to see how much influence the Soga family may have had in the royal bedchamber, something we would do well to remember as we look into this period.

And while the Soga family was on the rise, other families were not doing so well. In particular, it seems that something happened to the Ōtomo family.

Now don’t get me wrong, Ōtomo Kanamura, that veteran courtier, was reappointed as Ōmuraji at the start of the reign, and given all of his influence up to this point, he clearly had been doing something right. But then we have a single incident at the start of Ame Kunioshi’s reign that makes me wonder.

It took place during a court visit to Hafuri-tsu-no-miya over at Naniwa—modern Ōsaka. Hafuri would appear to refer to a Shinto priest, so apparently they were at the palace—or possibly shrine—of the Priest, at least as far as I can make out. When Ame Kunioshi went out, much of the court came with, including Ōtomo no Kanamura, Kose no Omi no Inamochi, and Mononobe no Okoshi. Of those three, Kose no Inamochi seems a bit of an odd choice, but we’ll go with it, for now.

While they were there, away from the palace, talking over various subjects, the conversation turned towards talk about invading Silla. At this, Mononobe no Okoshi related the story of how Kanamura had basically orchestrated giving up four districts of Nimna over to Baekje. Those were the Upper and Lower Tari, Syata, and Muro. This had pissed off Silla, who no doubt wanted as much of a buffer state between them and their allies as possible, and who also may have felt that Nimna and other border states were theirs to manipulate. Through all of these talks and deliberations, which apparently went on for some time, Kanamura stayed at home, out of the public eye, feigning illness. Eventually, though Awomi no Ōtoshi no Magariko came to check in on him and see how he was doing, and Kanamura admitted that he had simply been feigning illness to get out of the humiliation of having given up the provinces so many years ago.

Hearing of this, Ame Kunioshi pardoned Ōtomo no Kanamura of any guilt. He could put the past behind him and speak nothing of it.

And he did. Speak nothing of it, that is. Or at least nothing that was recorded in the Chronicles. From here on out, we don’t hear of Kanamura—and barely of Ōtomo. There is a brief mention of Kanamura’s son, Sadehiko, who had gone to the Korean peninsula to fight back in the previous reign. Then, another member of the Ōtomo pops up again in the reign of Bidatsu, but this appears to be the last time we see an “Ōtomo no Ōmuraji”—no other Ōtomo would be recorded as having taken that position, even though others, particularly the Mononobe, would continue to be honored with the title up through at least the 7th century.

Ōtomo no Kanamura’s exit at this point in the narrative seems somewhat appropriate, as the narrative will go on to focus on Nimna, and the violence on the peninsula. That fighting would consume much of the next century, with Silla eventually winding up on top, but that was not always a foregone conclusion. In the meantime there were numerous battles, back and forth. Sometimes it was Silla and Goguryeo against Baekje and Yamato. Other times, Silla and Baekje fought against Goguryeo. Then there were the smaller states of Kara, Ara, Nimna, and more.

With all of that chaos, the Chronicles record numerous people from the peninsula coming to stay in the archipelago, but also there were many ethnic Wa people—possibly from Yamato, especially based on their names—that went to live and fight on the peninsula as well. Family names such as the Mononobe, Ikuba, and even Kibi show up with Baekje or Silla titles, intermingled with other names of unknown, though likely peninsular, origin. This intermingling would appear to indicate that the states of the Korean peninsula were multi-ethnic states, with individuals from all over. Despite—or perhaps even because of—all the fighting, there seems to be an increased intercourse between the various states, as well as with states like the Northern Wei, to the West, in the Yellow River Basin, and Liang, to the South, along the Yangtze.

We’ll dive into all of that chaos and confusion—and try to draw a few more concrete facts and concepts—next time.

Until then, thank you for listening and for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Kim, P., & Shultz, E. J. (2013). The 'Silla annals' of the 'Samguk Sagi'. Gyeonggi-do: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253.

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1