Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

Alright, everyone, here’s your holiday episode: The tragic romance of Saho Hime. This episode was really a blast, and I can’t tell you how nice it was to be able to focus on a real “story”—I love the sleuthing behind putting together the different pieces of history, personally (that’s what pulls me down so many different rabbit holes), but this story is pretty cut and dried. Did it actually happen? Well, who knows. We are fairly certain they weren’t writing things down in this period, so it is unlikely to be entirely accurate. And of course they put a bit of a sheen on it to make the sovereign look to be justified and righteous. But the core story seems believable enough. Certainly there have been some stranger-than-fiction stories that really happened, so what does it hurt to accept it at more-or-less face value?

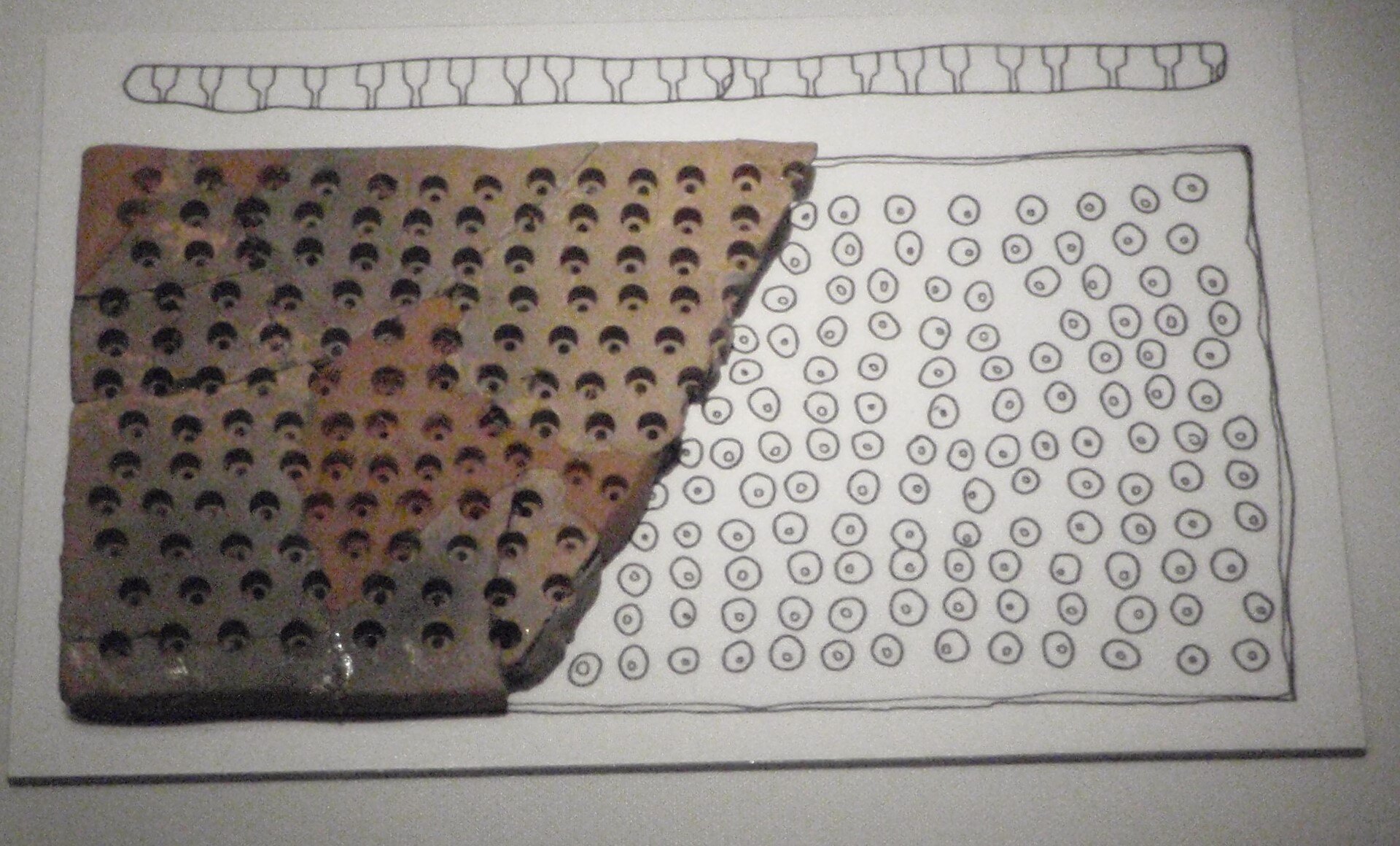

One thing out of this episode is a strangely named dagger—a dagger with a “multi-colored” cord. This may have referred to the creation of the blade, instead of an actual cord, but the multi-colored cord goes best with the story. It is unclear exactly what that would have looked like.

Dramatis Personae

Now I do want to address something that has come up, and I worried about this from the very beginning: keeping track of all of the different names and characters. And believe me, I struggle with this myself. The truth is, the chronicles weren’t really all that concerned with giving history and backstory and fleshing out all of the people that appear in it. In addition, as this is an English language podcast, I can only assume the lack of familiarity with the names can be pretty wild. Even if you know Japanese it doesn’t help, as many of the words that form the names have changed over the centuries in meaning or pronunciation—and in some cases we still aren’t quite sure where a name comes from or if it even is a true “name” as we would think of it. And don’t get me started about how many of these texts will happily use two, three, or four different names for the same person, sometimes radically different from one another. That said, let me try to at least capture the major dramatis personae in this episode.

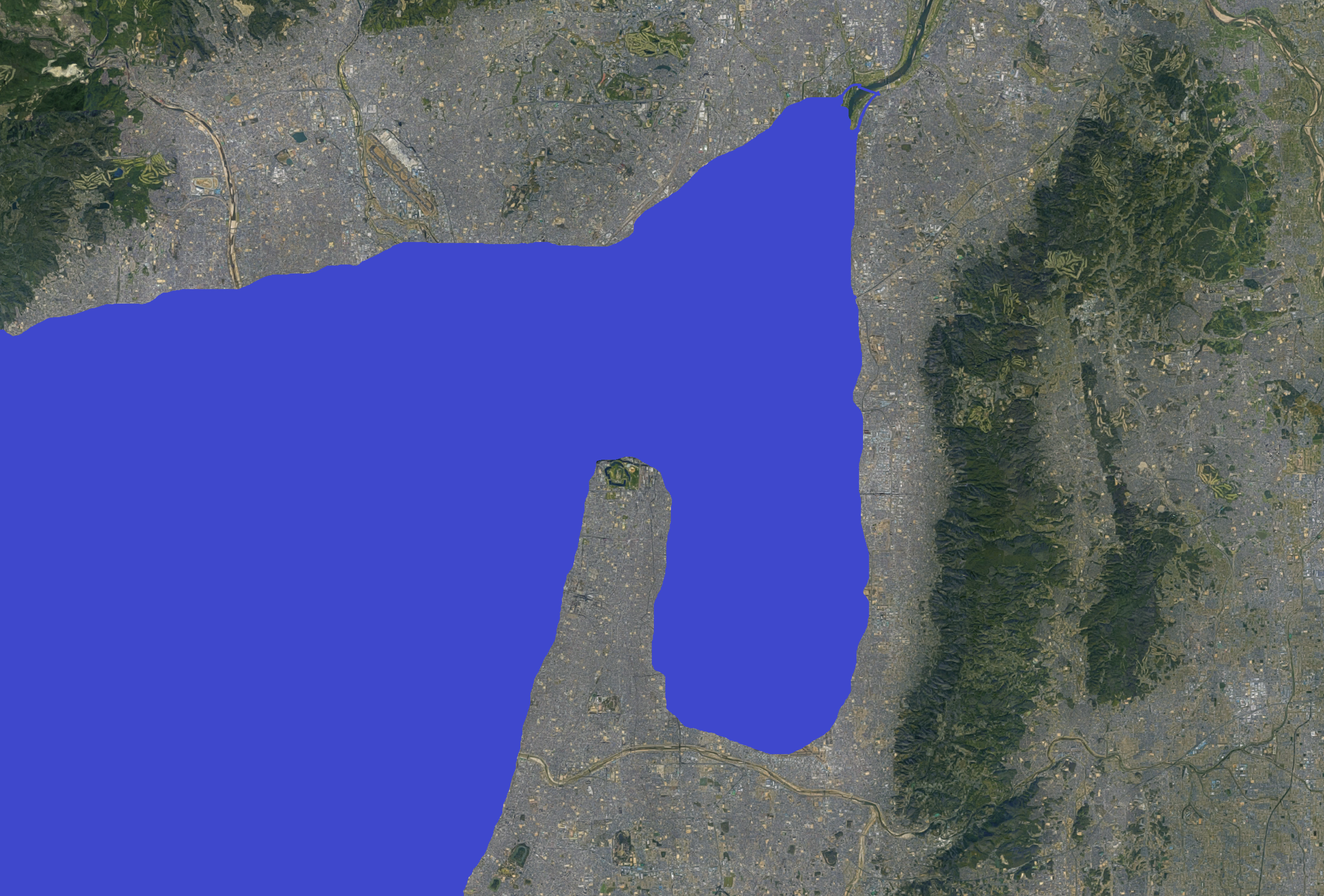

Ikume Iribiko Isachi - AKA Suinin Tennō (a 7th or 8th century designation), aka the Sovereign of the Tamagaki Palace. Ikume is the 11th sovereign of Yamato, according to the Chronicles. He is the son of Mimaki Iribiko, the previous ruler, and likely lived around the latter 3rd century, in my opinion. Though he is the focus of the Chronicles, in some ways the action more revolves around him than is caused by him, per se.

Saho Hime - AKA Sawaji Hime. I suspect that “Sawaji” may be her actual name, such as it is, but between her and her brother, it is just as easy to use “Saho” to demonstrate their relationship. Saho Hime was married to Ikume Iribiko when he first took the throne, though she has her own royal heritage. Her father is said to have been Hiko Imasu, and her mother was Saho no Ōkurami Tome. Hiko Imasu was the son of sovereign Waka Yamatoneko Hiko Ōhihi (aka Kaika).

So to quickly draw the lineages of Saho Hime and Ikume Iribiko, it would go like this:

Waka Yamatoneko Hiko Ōhihi -> Mimaki Iribiko Iniye -> Ikume Iribiko Isachi

“ “ -> Hiko Imasu - > Saho Hime

Saho Hiko - We only know Saho Hiko by his title. “Hiko”, meaning “Prince” or “Lord”, probably derived from “Child (of the) Sun”, and what I assume to be a place name, “Saho”. He is Saho Hime’s elder brother. We often run into paired names like this—Saho Hiko and Saho Hime; Aga Hiko and Aga Hime; even Mimaki Iribiko and Mimaki Iribime. Although we can see a gendered pairing, it doesn’t tell us if there are generational differences, nor whether the two are blood relatives or related through marriage or other means. So it could mean, effectively, Father-Daughter (often the assumption when X-Hiko gives up X-Hime to marry the sovereign or someone else), Brother-Sister (as appears to be the case here), or husband-wife (as with Mimaki Iribiko and Mimaki Iribime… maybe). It could even mean more than one of these relationships. There is also something of an assumption, in many cases, that X-Hiko or X-Hime have some kind of authority in the land of X, but this isn’t clearly the case, and it is possible that a construction is name+hime as it is that it is place+hime. I’ll try to go into more details on the titles we are seeing, down below.

Homutsu Wake - AKA Homuchi Wake, or Homuji Wake. The son of Ikume Iribiko and Saho Hime, either born in the “rice castle” or else just before and taken by his mother into the encampment. He is generally treated as though he either does not speak or else babbles, like a child, even as an adult.

Hiko Tatasu Michi no Ushi - From Tanba (or Taniha) Province. “No Ushi”, which we see a lot, is probably the origin for “Nushi”, meaning lord or master (e.g. Ōkuninushi). He is a son of Hiko Imasu—so technically a half-brother to Saho Hiko and Saho Hime, which could be why Saho Hime recommended his daughters, her nieces. Other than his role in providing daughters and linking back to Hiko Imasu and the royal lineage, we really don’t have much about him in this account.

Hibasu Hime - Daughter of Hiko Tatasu Michi no Ushi of Tanba. Mother of the next sovereign (#12) Ōtarashi Hiko Oshiro Wake.

Yatsunada - Related to Kōdzuke, aka Kamitsukenu, over in the Kantō region, though not clear if he is from that region or just that they are claiming descent through him. He is the general in charge of laying siege to Saho Hiko’s fortifications.

Aketatsu no Miko - Another grandson of Hiko Imasu. He accompanied Homutsu Wake to Izumo. “Miko” here refers to a royal prince. Many of the direct Royal Family are actually given the honorific “Mikoto”, but “Miko” actually appears on quite a few. Most of the time I am dropping it because the names are already long enough, and it isn’t always consistent between the various Chronicles.

Unakami - Also accompanied Homutsu Wake to Izumo. Not much else on them in this particular part of the Chronicles.

Kihisatsumi - An ancestor of the Izumo no Miyatsuko, but otherwise a somewhat random introduction.

On the subject of titles and honorifics

So with all of these names, it may be helpful to go over a few of the name elements that keep showing up over and over again.

Hiko/Hime - Perhaps the most common one that we come across. It appears to derive from “child” or “woman” (respectively) of the Sun. Originally pronounced more like “Piko”/“Pime”.

Iribiko/Iribime - Similar to Hiko/Hime, this appears around the time they start talking about the 10th sovereign, Mimaki Iribiko.

Mikoto/Miko - These appear as honorifics. “Mikoto”, using different kanji, is used for the kami during the Age of the Gods, and eventually also used for various members of the royal house and others. “Miko”, as noted above, is also found specifically for royal princes. I assume it is related to “Mikoto”, as in some chronicles we see “Miko” and others “Mikoto” for the same individual. I often drop this in the podcast, and it is always at the end of the name. The others show up in the middle or even beginning of the name, so it is harder to really just drop them, and often, like with Saho Hime/Hiko they are distinguishing elements. “Mikoto” appears to have no particular gender.

Wake - This one shows up in the name of our next sovereign. It is considered a kabane title for members of the royal family

Miyatsuko - Chieftain/Provincial governor. Usually of the form “Province name” + “no Miyatsuko”. So like the Izumo no Miyatsuko.

Other Kabane - Other kabane ranks that show up are Omi, Sukune, Muraji, Atae, etc.

Other possible titles - There are other types of apparent possible titles that aren’t clear, but sure seem like that to me. For instance: “Mimi” and “Tohe”. These appear to be local lords or chieftains. Often these appear in constructions where “tsu” is used as a genitive particle (vice “no”).

References

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1