Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode starts our look at the events that were said to have occurred during the reign of Wohodo, aka Keitai Tennō. Before we get into the text, though, we will be looking at some of the other evidence, so that we have a foundation for what we are reading about.

A Quick Note About Maps…

So maps can be extremely helpful to us. They often let us relate to the geography and what is going on at a macro level. I love looking at topographical maps of historic places to get a feel for some of what people saw back in the day. However, we have to be careful, because maps can also be a distraction and even an outright lie. Even geographical features may change over time, sometimes in ways that seem inconceivable.

This is even moreso with political boundaries. Even with legal structures detailing exactly where a boundary is supposed to go, is that agreed upon by all of the parties involved? There are plenty of disputed territories, with overlapping claims. This gets even more murky when we are seeing maps of territories that are supposedly being controlled by polities without a clear code of just what constitutes their territorial borders. In many cases it was likely more people and communities that made up early polities, not land, and the tenuous bonds that sometimes formed meant alliances could change and shift. Furthermore, political and ethnic boundaries often overlap in seemingly odd and inconsistent ways.

When someone makes a map without clear guidelines for where the boundaries are, they must rely on their own judgment. That judgment is often tinged with their own biases—in the case of our current studies, maps are often heavily influenced by ideas of national pride. Maps can easily be a type of propaganda, whether intentional or otherwise. Therefore we need to be careful. This is even more true when we are dealing with sources that are not exactly crystal clear.

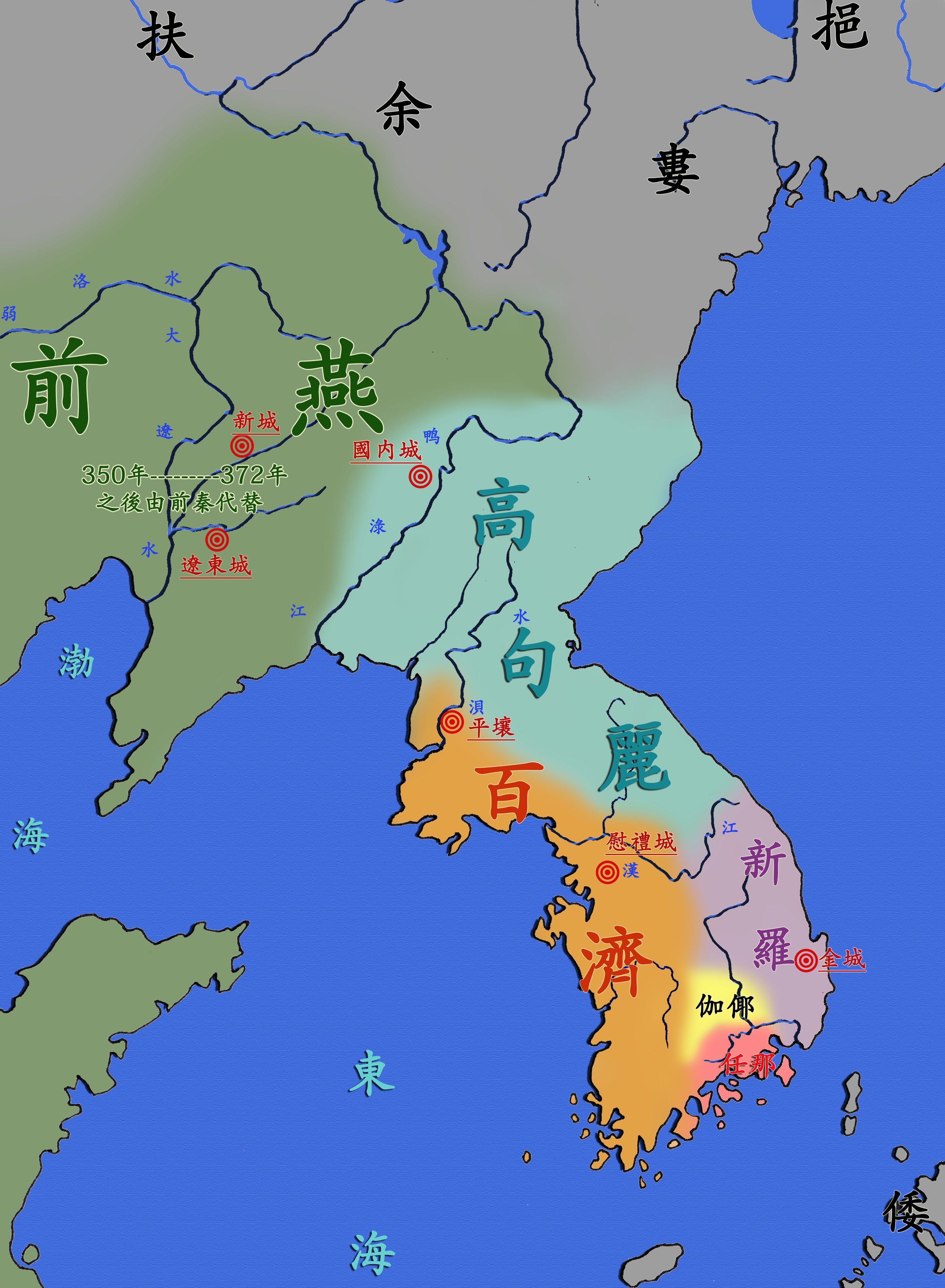

Below, I’ve pulled four different maps that people have made of the Korean peninsula around the time we are talking about:

A map showing Goguryeo, Baekje, Silla, Nimna (Imna), and Japan. Here it makes Nimna a fairly large state that encompasses parts of what others have called Baekje and Kara (Gaya). This Japanese territory image above was made by Maximilian Dörrbecker (Chumwa), Image:Japan_admin_levels.svg, Wikimedia commons. The file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license., CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

This map shows the Three Kingdoms, as well as Kara and Nimna, but the latter are definitely small and reduced. By Evawen, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This map purports to show the extent of Nimna in 520. Note that it is much reduced and gives over a lot of surrounding territory to either Silla or Baekje. With no apparent appreciation for Kara, again, which is assumed to be a part of Nimna. 520年的任那地图 by 金楼白象, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Another map of the Korean peninsula, but this one is trying to connect various settleents. It shows Kara/Gaya, but in the same color and in lesser font compared to Nimna/Imna. Silla and Baekje also appear reduced in size, comparatively. By マンスニード, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Taking a look at the maps you may notice how some have “Nimna” (任那) covering the entire southwest corner of the peninsula. Others give that to Baekje. The location of “Kara” (加羅) likewise is shifted around. Some maps even get rid of one and add both. Then there is the island of Jeju, or Tamna (耽羅), which may or may not even be included.

Of course, none of these “borders” really exist. There may be certain communities, but particularly at this time, loyalties appear to be fluid, given that, in the end, there was little capacity to really control what was going on at the far peripheries. For any polity we may be able to identify a strong presence in a given area, but the that will fade the farther you go from that central area.

This is further exacerbated by the fact that our written sources place everything in the context of the later kingdoms. For much of the territory, we have few written records—typically only when they come in contact with a larger polity and even then it isn’t like we are given clear directions on how to get there, because that wasn’t important.

The takeaway that I would recommend is to assume that there is a lot going on that we are not aware of, and that isn’t getting written down. There are a lot of smaller polities doing their thing, invisible to other forms of history.

Ethnic “Wa” and Peninsular Japonic Speakers

Issues with maps similarly affect other studies, including linguistics. While there is a general agreement that the Wa in the archipelago arrived via the Korean peninsula, it gets much trickier if we look at any traces of their existence on the peninsula. They must have been their—or at least their ancestors—for them to have come over, but what happened to them? Korean is not a Japonic language, despite some older theories and some superficial similarities, and at some point it is clear that the Korean language came to dominate the entire peninsula, likely through the rise of Kingdoms like Baekje, Silla, and Goguryeo. Unfortunately, what we do have from the early period when Japonic may have been spoken is written down in classical Sinitic characters—kanji, or hanzi—and grammar. Without something like the Man’yoshu— a collection of poetry written in the Japanese vernacular, but using various kanji for their sounds— how do you know how a word is pronounced?

Aston and others often take the easy way out, and just use modern Korean, assuming that would be the closest. However, there is evidence that this isn’t the case. For instance, some of the Korean records talk about how the rulers would deliberately change the names of certain places into their own language, indicating that those old placenames held some vestiges, at least, of an earlier language.

Rather than a Korean pronunciation, it has been suggested that we look at Old or Middle Chinese. Assuming many of the earlier scribes are described as ethnic Han, and the local scribes would be learning the Chinese of their day, and so it seems likely that they would be reading it that way as well. When choosing what characters to use to represent a given word, they were probably using that pronunciation. That’s how we get things like “Nimna” v. the modern Korean “Imna” and “Kara” v. “Gaya”. Over time, Japanese and Korean readings Kanji/Hanja (Sinitic characters) started to drift apart, and we cannot always trust that modern On’yomi or Eum-dok readings were the same in the early period when these names were first being written down.

Viewed critically, there are words—primarily placenames—that scholars like Alexander Vovin have identified as seemingly quite Japonic in nature. On the flip side, scholars have also pointed to some placenames in Japan and suggested a Koreanic origin for them—that said, the Japanese chronicles do not deny that people from the Korean peninsula—likely some of them being Koreanic speakers—were settled in parts of the Japanese archipelago. Some were even made members of the Yamato court and eventually would be listed as the ancestors of prominent Japanese families.

And so there is a question as to why we think this wouldn’t work the other way around. After all, as Yamato expanded their power, someone was on the losing end of that arrangement. Why wouldn’t they flee to the peninsula? And then there are the people still on the peninsula, who may or may not have been directly under a given polity, who could also be ethnic “Wa” and speaking some Japonic language, possibly one that has since been forgotten.

And this brings us to the island nation of T’amna.

T’amna or Tanimura

Jeju island, site of the ancient kingdom of T’amna. Image in the public domain per Wikimedia Commons.

The island of Jeju sits off the southern tip of the Korean peninsula. Due to its location, it is easily isolated from much of what was going on, and yet not so far out that travel was not attainable. Its position meant that it remained largely independent right up into the first few years of the 15th century, when it finally came under direct control of the Joseon court.

The Kingdom of T’amna first enters the narrative in the 5th century according to the Korean chronicles—and in the 6th century in the Japanese. It is a great example of the kind of place on the periphery where we have little to no actual documentation until much later. By the time documents are being written down locally, they appear to have adopted a Koreanic language, but some words and placenames suggest that the people were, at one point, speakers of Japonic. Old renderings of the name suggest that it was something like “Tammura”, which Vovin connects with “Tanimura”. It certainly seems plausible, and there have been some investigations into the language of Jeju island. From the time of Unified Silla, however, it was a tributary state of peninsular powers, and it appears to have adopted peninsular language, culture, and more, though with its own unique character.

Yeongsan River Basin and Keyhole Shaped Tombs

Moving on from just linguistics, we can take a look at the archaeological evidence and see that there was a lot more going on in this region than just what the written sources tell us. The Yeongsan River basin has its own unique archaeological features. For instance, they have their own burial practices, similar to the other mounded tomb cultures around them, but still their own. Early on they used jar style burials—jars were used as coffins, basically—that accreted into a single mound, sounding not dissimilar from the funkyūbo burial mound at the Yayoi site of Yoshinogari in Kyūshū, though with their own characteristics. These evolved and changed over time.

In the late 5th to early 6th centuries we find a different kind of tomb mound that suddenly appears in this region: keyhole shaped mounds. These again bear a superficial resemblance to similar mounds in Kyūshū, which were, themselves, copies of what was going on in the kinai region of the archipelago. The mounds in the Yeongsan area—initially found in Gwangju and the surrounding Jeolla region—use local construction techniques to build mounds no larger than about 50 meters. They have a horizontal entry chamber and a coffin, similar to later kofun tombs, but they use a Baekje style coffin, complete down to using nails that had to be imported from Baekje for the task. The grave goods include items from Baekje, Silla, as well as the rest of the peninsula and the archipelago, suggesting that the people of this area were well connected.

Only 14 of this style of tomb mound have been identified, and it died out quickly in the early 6th century. The fact that they had this practice—unique for the region—and yet we don’t know more about it just heightens the mystery surround them.

And that really carries us through to the theme of this episode—there is a lot we don’t know, and which the Chronicles still won’t tell us. Even if we assume everything that is mentioned in the Chronicles themselves is valid and occurred, there were so many other things going on and interactions that never get mentioned or written down. Entire states could have flared up and died off without a mention in some of these regions, especially as the Chronicles were focused, themselves, on the central polities, for the most part.

What we can generally assume is that differences were more gradations than anything concrete. There had been cross-strait interaction for centuries, with no reason to believe that things suddenly came to a stop, and it is likely that smaller polities could move and change in ways that larger, more established nations would not. National culture and politics—something that we don’t yet see so much of at this point—is a different game, as it is often a very clear “us” v. “them” mentality that encourages individuals to pick and choose sides. In this period, most people were probably more loyal to their village and their immediate neighbors rather than to some far away sovereign or national identity, allowing them to also be much more fluid in other ways as well.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is Episode 76: Cross-strait Relations, Part I.

Before I get too much into it, some news: we are expanding to YouTube. I’m honestly not sure how this will work, but we are converting some of our audio into playable videos—not that the visuals are that exciting but it at least gets it out there in another format. More information towards the end of the episode.

Now, as a reminder, we are still in the start of the 6th century. Last episode we saw the elevation of Wohodo, aka Keitai Tennou, around the year 507.

These next two episodes we are going to look at what was going on—or at least what was recorded as going on—during the reign of Wohodo, aka Keitai Tennou. Much of what we see in the Chronicles seems to really be more about the story of what was happening on the continent. In particular, we are seeing a lot of pushback against Wa and the Wa-aligned states on the peninsula. Understandably, these states are all mentioned in the Chronicles as though they are directly controlled by Japan, or Yamato, but this is definitely an anachronistic 8th century view. A lot of what we have appears to be from the Baekje Chronicles that the compilers of the Nihon Shoki were drawing from, but there is definitely a pro-Yamato spin to everything, so keep that in mind.

Also, this episode will likely be short, but that’s partly because some of this stuff is dense, and I don’t want to throw too much at you at once. Feel free to hit me up with any questions you might have and check out our podcast website for more information in an attempt to try to keep all of this straight.

Last episode, we discussed Wohodo’s background and how he apparently came to power to head up the third dynasty of sovereigns. During all of that, we noted how the Chronicles connect him with figures from the past, including Homuda Wake and Ikume Iribiko. Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, was famously considered to have been still in his mother’s womb when she supposedly went to war and brought the countries of the Korean peninsula to heel. Okinaga Tarashi Hime, aka Jinguu Tennou, was long credited with setting up the country of Mimana, aka Imna or Nimna, as a Wa state, an extension of Yamato’s power. However, it is much more likely that it was an existing state—possibly of Wa or at least a Japonic speaking people—and its existence is independently confirmed in numerous other records, though they don’t necessarily corroborate Yamato’s claim to it.

In this first episode, we are going to take a look at what was happening across the straits, between the southern tip of the Korean peninsula and the island of Kyushu, for the most part. This is a fraught area of discussion. Nationalist histories from both Japan and Korea have generally come to an uneasy truce that puts Korea and Korean culture and people on the peninsula and Japan and Japanese people on the archipelago. This all goes back to at least World War II and the use of Jingu and the Mimana Nihonfu, or the Japanese Government of Nimna, which was used as a justification for Japan’s invasion of the Korean peninsula.

Since then, scholars have generally agreed that there was no Japanese Government overseeing territory on the Korean peninsula. For one thing, there was no “Nihon” for there to be “Nihon-fu”—it would have been either Wa or Yamato, either of which have much different connotations. Furthermore, even if there was a government office of some kind on the peninsula, it was likely more of a diplomatic outpost than any kind of administrative unit. On top of all of that, we don’t’ even know where it was, other than some vague ideas.

If you go to Wikipedia, or do an Image Search for the Three Kingdoms period or just about anything we are going to discuss today, you often see well demarcated territories on the maps. Baekje will likely start somewhere up near Seoul and encompass the entire western half of the southern peninsula. Silla will likely be portrayed similarly, at least down to the Nakdong River Basin, where the map may show an area known as the Gaya Confederacy—sometimes even the Gaya Kingdom. Nimna—or Mimana—is often not shown at all, unless you are looking at Japanese maps of this time.

And yet the truth is that this is all much more complex. Most of our history for this period is based on texts. But those texts have flaws. The texts from the Sinic dynasties out of the area of modern China are perhaps the most reliable, but they have scant information to tell us exactly where things are, and while some states and proto-states are listed with fairly consistent names and descriptions, this isn’t universally true. Meanwhile the Baekje annals held by the Japanese court may have been a gold mine of information, but we only get the pieces that the Chroniclers chose to include, and from what we can tell it is clear that they often changed and quote-unquote “corrected” various details in order to present the story they wanted to tell, which was meant to aggrandize the royal line of Yamato.

Finally, there are the Korean sources, such as the Samguk Sagi and Samguk Yusa, as well as the Tongkam. These are all invaluable sources, but they are no less biased than the Japanese Chronicles. They were compiled centuries later—even later than the Japanese Chronicles—and it seems they were drawing from different versions of events in many cases. The fragments of the Baekje Annals that we have in the Nihon Shoki occasionally lines up with the Samguk Sagi, but often it speaks to periods where the Samguk Sagi is otherwise silent. It doesn’t help that all of these accounts are focused on the actions of the center, and often ignore the periphery. We don’t have written Chronicles out of Gaya—or Kara—for instance, nor any other polities that may have existed on the peninsula at this time.

It further obscures things that this was all written in a form of classical Sinitic—Chinese characters—that did not match up with the languages being used on either the peninsula or the islands. In addition, many of the Korean sources are often using names that were deliberately changed when Goryeo took over—obscuring many local details by replacing placenames, one of the things linguists often rely on, with their own, ensuring that even if there had been another linguistic group, its legacy was largely erased from the landscape, leaving us to puzzle through the scraps.

That we are, today, reading through yet another lens also obscures what we see. In Aston’s English translation of the Nihon Shoki he often makes the choice to render some words into the modern Korean equivalent of On’yomi, using the Korean “Chinese” pronunciation of the characters, especially where it is clear we need a phonetic spelling. Names are often assigned a nationality, as though the modern nations of Korea and Japan already existed as linguistic entities from back in this period.

This idea, that there were Wa or Japonic states on the peninsula separate from Yamato, is worth examining a little more, and here’s where we should touch once again on language. We talked somewhat about this back in Episode 9, where we discussed theories on the origins of the language of the Wa. Current scholarship seems to indicate that there was a Japonic—or proto-Japonic—speaking people on the Korean peninsula prior to the arrival of the Korean language. This may not have been the only language on the peninsula, and we certainly know of a variety of ethnicities that show up briefly in the record, but I’m not sure how we would even be able to tell what languages such people spoke, as Korean eventually moved along the peninsula, north to south, taking over and pushing out any indigenous languages. The state of Baekje may have had Japonic speakers, beyond those Wa who were recruited into the court and military structure, but it was likely largely speaking a language similar to Goguryeo, given their ties through purported Buyeo ancestry. Likewise there is some evidence in Silla for a Japonic substratum, though even they had largely adopted the language used by Goguryeo and Baekje by the 6th and 7th centuries. So even if the dominant language of the main states on the Korean peninsula was largely Korean and not Japonic, it certainly seems reasonable that there were some Japonic speaking holdouts on the peninsula, and perhaps they even identified with the larger Wa culture. I’ve seen less evidence for the lands of Nimna and the independent lands of the Kara confederacy, but that’s hardly surprising given the paucity of sources for what was going on in that region.

At the very least it seems reasonable that these lands, which were at one end of the standard trade routes between the peninsula and the archipelago, would have a special relationship with Yamato and the people of the Japanese islands. Kara, and the many lands there—Kara, South Kara, Ara, and more—are identified as independent and having their own sovereigns and rulers. Nimna, likewise, is noted as having a “king” at one point in the narrative, and continually shows up as separate, in ways that lands like Tsukushi, Kibi, and Izumo do not. This is mirrored in the way that the records of the Song also list Nimna and Kara as separate lands, as opposed to those on the archipelago.

Key here to realize is that language is not culture is not ethnicity. Just because someone speaks a Japonic language that does not make them Japanese—take, for example, the old kingdom of Ryukyu, which was an independent entity for centuries. There is a false dichotomy presented by the idea that all of the peninsula must speak Korean and all of the archipelago must speak Japanese that concludes that if there are any Japonic speaking people on the mainland then they must, obviously, be a part of Yamato’s growing confederacy. Similarly in the other direction. However, remember, that the immigration went fairly clearly from the peninsula to the archipelago, not vice versa.

Evidence of this might exist with one more location that we’ll introduce this episode, and that is the land of T’amna, known today as Jeju Island. T’amna is interesting—it was an independent state off the coast of the Korean Peninsula, and while it became a tributary state to the larger Korean court, the kingdom of T’amna retained local independence up through the start of the 15th century. So when we talk about the Three Kingdoms on the peninsula, even as the old states of Kara were absorbed into Silla and later Goryeo, T’amna retained an independent character up until the Joseon dynasty.

Unfortunately, we don’t seem to have much written down from T’amna itself, at least not in the early centuries. Later on, legends claim it was founded an impossibly long time ago, but it enters the historical record some time around the Han dynasty. The Samguk Sagi identifies early relations with Baekje by 476, and it seems solidly in the records from at least the 5th century onwards. Indeed, it pops into the Nihon Shoki fully formed.

Of interest, currently, besides the fact that it shows up in the Nihon Shoki at this time, is that recent investigations into the linguistics of placenames and other features of the island suggest that Tam’na or Jeju had a language different from much of the Korean peninsula, and that language may very well have been a Japonic or proto-Japonic language, along with many other groups in the peninsula. Indeed, even the name “T’anma” is sometimes expressed, early on, as something more like Tanmura, or possibly Tanimura. While it eventually adopted the Korean language that spread from the north and was taking over the peninsula, it may have retained some of these underlying Japonic elements for some time, especially if we assume that the spread of Korean took place from the Buyeo people through Goguryeo and Baekje southward, with the southeast of the peninsula containing the last hold-outs. It would make sense that an isolated island would retain pre-Korean traits for much longer.

Certainly the island had close ties to Baekje, and it seems to further support the idea that there were Japonic speaking people on the Korean peninsula. Furthermore, there is no evidence that I’ve seen that would make it part of the larger Yamato confederation. No doubt they interacted, as did all the various states of this period, but there is nobody I have seen making the claim that Yamato somehow claimed ownership of the island state of T’amna.

Given all of this, a better approach might be to see culture from the peninsula to the archipelago as more like a color chart. While there are centers, such as Baekje’s capital of Ungjin, Silla’s capital at Gyeongju, and Yamato’s capital in the Kinai region of Honshu, we don’t have hard lines of control between any of them, and rather we have gradations of difference. Those differences aren’t always easy to see on the periphery, where our sources tend to peter out.

Another source that we need to consider, besides the textual and linguistic, is archaeological. I admit I am not prepared to get into a full-blown archaeological discussion of the Korean peninsula as compared with the Japanese, and this is an area where a lot of work is still being carried out. Still, I think it is useful to consider some broad strokes.

First off, we can use archaeology to see some of the similarities and differences between different groups. We can see a difference in Silla pottery styles, even as they influenced the sueki ware in Japan that was likely the product of peninsular people in the Kawachi region. Armor from tombs in the archipelago has clear ties to armor found in the region of Kara, around the Nakdong River Basin. This all makes sense as Kara would have then been at one end of the easiest path across the straits, island hopping via Tsushima to Northern Kyushu and beyond.

There are some areas, though, where the archaeological record causes us to pause. For example, In the late 5th to early 6th century we even see examples of keyhole shaped tombs in the Yongsan River Basin, though with some very peninsular affectations, suggesting that it wasn’t just a whole-cloth importation of culture from the islands. As we’ve discussed, keyhole shaped tomb mounds on the archipelago are often interpreted as indications of the spread of Yamato influence, but in this case we have to wonder.

In the southwest of the Korean peninsula, along the Yeongsan River, that area is usually described as part of Mahan and later Baekje, but archaeologically, there are some distinct features in Southern Jeolla—or Jeollanamdo—particularly in this region, around modern Gwangju. Unfortunately, very little in the Chronicles from either side of the strait really gives us many textual clues for what was going on there. We can assume they had their own small states or proto-states, but they are often just lumped in with the larger Baekje. And so we are left with conjecture.

What we do know is that sometime in the late 5th century, people in Jeollanamdo started building keyhole shaped tombs with local construction techniques that otherwise look very similar in shape to those from the archipelago. Inside, however, the coffins follow Baekje patterns, to the point of using nails that would have been imported from Baekje, to the north. At the same time there are Wa style long swords and magatamas—the comma shaped jewels—Silla crowns, and Baekje prestige goods. They also had local style prestige goods as well.

So, it’s a fascinating mix of cultural influences – but scholars have no idea who these people were. Were they refugees from the archipelago, trying to create a new polity on the continent? Were they originally from Baekje, but just enamored of the style on the archipelago? Or perhaps even some combination of both? Maybe even none—perhaps they were local magnates who were borrowing ideas from all of their neighbors. In all, about 14 of these tombs have been discovered in and around Jeolla, and they were all built in the late 5th to early 6th century—so within the lives of only one or two generations. And then they disappear. There may be some clues in Northern Kyushu, however, where there have been found some tombs that share some of these Jeolla characteristics, and they have been found near settlements that appear to show evidence of ondol, a peninsular underfloor heating system that was quite popular on the peninsula, but which otherwise never caught on in the archipelago—or so we thought. But in some of these settlements in Northern Kyushu, which have traditionally had relatively close ties with sites across the straits, it seems someone may have at least been giving it a try. Unfortunately, just as Jeolla gets little mention in Korean sources, Northern Kyushu, or Tsukushi, often gets minimal attention by the Japanese written sources.

I bring all this up just to re-emphasize that there is a lot more going on than we have written down, with entire generations and cultural shifts happening. This comes into play in this period as we are going to get a lot of different actors coming onto our stage, sometimes with just a single line and then nothing more. The histories that are taught in classes will often streamline all of this, pruning what we don’t know so that we can focus on the threads that are most important. To a certain extent, I’m forced into this as well, but keep in mind that there is a lot going on, and a lot yet to discover. Hopefully archaeological discoveries will continue to advance our knowledge of this period, and we need to be careful about being too wedded to our interpretation of the textual sources, alone. Furthermore, just because we know the outcome, today, realize that in that moment there was potential for dramatic shifts and changes. States that may have seemed like the next big thing may have suddenly collapsed, like a well-hyped movie of a popular franchise that bombs at the box office, largely forgotten. This could be due to any number of reasons: war, natural disaster, or just general misfortune. And without clear indications, we may never really know the reason.

What we can see is that the Chronicles indicate is this was a period of regional instability. Baekje had been defeated and was reconstituting itself to the south, in Ungjin, but it would take until the early 6th century before things started really looking up again. Yamato’s last Great King to have much influence appears to be Wakatakeru no Ohokimi, aka Yuuryaku Tennou, in the late 5th century, and the chronicles then detail a succession of sovereigns whose reigns were notably short and often focused on Yamato, rather than the larger world. See Episodes 60 to 70.

And then of course we get our current ruler, Wohodo, aka Keitai Tennou, coming in from out of the blue entirely. Yamato was hardly stable, and when the center was in chaos, it traditionally means that the periphery had a freer reign to innovate and grow and try their own thing. And so it is not uncommon to see strongmen rise up and try to challenge major powers. Elites who are on the outs in the various courts may flee and in so doing, bring their own stamp of legitimacy to places on the outside, as well as bringing with them ideas of state formation and governance.

This is the environment we likely find ourselves in around the beginning of the sixth century, and much of the action appears to be focused on the Baekje annals in the Nihon Shoki at this point, which themselves seem largely focused on what was happening in what we assume is the southeast corner of the Korean peninsula.

We’ll talk about the various lands, such as Ara, Panphi, T’amna, and more. Much of this is focused on the smaller polities, though within the context of the manuevering between Baekje, Silla, and Yamato. That other states often have a seemingly equal—or even moreso—seat at the table could be an indication of just what kind of state the various powers were in. Even if they were ascendant, they did not have a free rein to just do whatever they wanted, and some of these local elites were clearly posing a challenge to their own ambitions.

Soon enough, the situation would change. Spoiler alert, but the largest state in the Gaya confederacy, Geumgwam Gaya (?? Kara?), which may have just started to rise as an independent kingdom, would soon fall to Silla, but that was not necessarily a foregone conclusion, something we should remember as we watch events unfold.

With this background, we can get into the actual stories from the texts in our next episode, where we’ll talk about what the Chronicles themselves have to say about all of this, primarily focused what was going on across the straits, between the archipelago and the peninsula. There is the continued story of what was going on with the various states of Nimna and Kara, with Yamato’s ally, Baekje, and their greatest rival, Silla. We’ll touch on the Iwai Rebellion, when Kyushu tried to cut off Yamato’s access, and more.

Until then, thank you for listening and for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate on Patreon or through our KoFi site, ko-fi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the links over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

Also, feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com. It is always great to hear from people and ideas for the show.

Also, as I noted up front, we are starting to put videos up on YouTube. So far these are older episodes, and it does take some labor to convert them—and I have over 70 episodes to go through, so this will likely take some time. Still, if that works for you, you’ll be able to find us and subscribe at Sengoku Daimyo on YouTube—just look for the Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan playlist.

In addition to that, I’m looking for how best to get transcripts out there for you all. I’d like to make sure that our podcasts are accessible, and I know that is an issue without transcriptions available—and some of the original scripts for the first few episodes seem to be missing, so there’s that. If anyone knows of a good Speech-to-Text option (preferably free, but we’ll pay if need be), I’d really appreciate it.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Lee, D. (2018). Keyhole-shaped Tombs in the Yŏngsan River Basin: A Reflection of Paekche-Yamato Relations in the Late Fifth.Early Sixth Century. Acta Koreana 21(1), 113-135. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/756453.

Barnes, Gina L. (2015). Achaeology of East Asia: The Rise of Civilization in China, Korea and Japan

Lee, Dennis (2014). Lecture: “The Significance of “Korean” Keyhole-shaped Tombs in the Study of Early “Korean-Japanese” Relations”. https://vimeo.com/112210901

Vovin, Alexander (2013). "From Koguryǒ to T’amna*: Slowly riding to the South with speakers of Proto-Korean." Korean Linguistics 15:2. John Benjamins Publishing Company. doi:10.1075/kl.15.2.03vov

Bentley, John R. (2008). “The Search for the Language of Yamatai”. Japanese Language and Literature (42-1). 1-43. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/30198053

Soumaré, Massimo (2007); Japan in Five Ancient Chinese Chronicles: Wo, the Land of Yamatai, and Queen Himiko. ISBN: 978-4-902075-22-9

Kiley, C. J. (1973). State and Dynasty in Archaic Yamato. The Journal of Asian Studies, 33(1), 25–49. https://doi.org/10.2307/2052884

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1