Previous Episodes

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we talk about Katsuraki no Sotsuhiko, covering what we know of the stories he is in as well as discussing what might be lurking behind these stories.

Katsuraki no Sotsuhiko

The names we find in the Chronicles are primarily 「葛城襲津彦」 (Katsuraki [no] Sotsuhiko) in the Nihon Shoki and 「葛城長江曾都毘古」 (Katsuraki [no] Nagae [no] Sotsuhiko) in the Kojiki. In the Old Japanese of the Kofun period it is probably something like Kaduraki [no] Sotubiko. Old Japanese had many differences from modern Japanese pronunciation, and is a study unto itself.

The other name we see is from an excerpt from the Baekje annals in the Nihon Shoki, and it is「沙至比跪」(Satibiko). There is technically the possibility that this story is about someone else, or that the Baekje Annals themselves had it wrong, in the first place. The general consensus, though, appears to be that these figures are, indeed, referencing the same person.

The idea of him being a high ranking chieftain, and possibly one of those responsible for the trade routes with the continent—after all, there were only so many ways to get from the archipelago to the peninsula—is intriguing. Perhaps he was some sort of King. However, I would also note that the excerpt from the ancient Baekje Annals, which is no longer extant, other than the fragments in the Nihon Shoki and other histories, like the Samguk Sagi, does not refer to him as the sovereign of all of Yamato, and puts him in a subservient position. That said, it is clear that the Chroniclers tinkered with the wording of the Baekje annals in places. Sometimes it was simply to update words to increase understanding, such as changing “Wa” to “Yamato”. It would have been easy enough, however, for them to “clarify” something in such a way that it changed the meaning to better suit what the Chroniclers knew to be the truth, so even here we can’t be entirely sure that we are getting a faithful transliteration. Still, it seems reasonable to assume that Satibiko—or Sotsuhiko—is, indeed, the one being referenced here.

Ame no Hiboko

You might recall the “Heavenly Sun Spear”—「天日槍」in the Nihon Shoki or「天之日矛」 in the Kojiki—from our earliest discussions of relations with the continent. He was said to be a Silla prince who eventually settled in the area of Kehi, along modern Tsuruga Bay, where he came to be worshipped as a kami. Of course “Ame no Hiboko” is a Japonic name, and unlike other names on the peninsula. He might be the same, however, as the man named Sonaka (or Tsunoga) Shichi (or “Cheulchi” in modern Korean). Some accounts have his origin in Silla, while others point to Nimna and the confederated Kara states. In some stories he even has a title that would appear to equate to about the 3rd rank of the Silla court.

The Chronicles make Katsuraki no Sotsuhiko one of Ame no Hiboko’s descendants, and provide yet another connection to the areas of Silla and Kara on the southern Korean peninsula.

Takechi no Sukune

We just talked bout him last episode (Epsiode 46), and while the Chronicles suggest he was Katsuraki no Sotsuhiko’s father, there is enough evidence to question whether or not that was actually the case.

Okinaga Tarashi Hime

Also known as Jingū Kōgō (神功皇后), she was the sovereign who is said to have “subjugated “ the Korean peninsula for Yamato. She is also connected to the Katsuraki family, through her lineage, and some of the earliest stories about Sotsuhiko happened, ostensibly, during her reign.

Homuda Wake

The sovereign for most of this period that we have been discussing, aka Ōjin Tennō (応神天皇). We’ll cover more on him next episode.

King of Kara and his Sister

The King of Kara is referenced as “Kwi-pon” in the Aston translation (己本旱岐—Kwi-pon Kanki). Aston goes on to note that the Dongguk Tonggam, a 15th century compilation of Korean history, gives the sovereign at this time as “I Si-Bpeum” (伊尸品). It is possibly a transliteration error, or it could be the difference between the king of Geumgwan Kara, the primary city-state of the Kara confederacy, or it could be that this is a different '“King” altogether. We have little to go on besides what is written here.

It is interesting that he is given a similar Silla rank to Ame no Hiboko, that of Kanki. I don’t know if this was added later or if it is indicative of Kara kings accepting court rank from Silla, similar to how other states sought out titles from the Wei and Jin courts, a practice we will go over in more detail in a later episode.

His younger sister’s name is given as 「既殿至」, which Aston translates as “Kwi-chon-chi”. Unfortunately, I don’t have enough information on the language of Kara to give you anything more, but it is likely better than reading it using modern Japanese on’yomi. This is the younger sister who then goes to the court of the “Great Wa” to complain about “Sachihiko” not following through with his orders.

Mongna Geunja

Mongna Günja (or Mongna Künja—possibly even something like Mong Nagunja: 木羅斤資) is a Baekje general who shows up during the reign of Okinaga Tarashi Hime, helping out with the Baekje-Wa alliance and later chasing down “Sachihiko” and stopping the assault on Kara. Later he would have a son (with, interestingly enough, a Silla wife) who would have his own role to play in pen-insular events.

Yutsuki / Kungwol

Specifically this individual is referenced as “Yutsuki [no] Kimi” (弓月君)—Lord Yutsuki or Lord of Yutsuki. Yutsuki here is the traditional pronunciation in modern Japanese, and the Korean would be something like Kungwol (and the characters at that time may have been something like “Kung-ngwet” based on a Middle Chinese reading of them). The Chronicles don’t specify exactly where they are from, which has given rise to various theories, many of them trying to connect Yutsuki to someplace in modern China or even out in the Xinjiang region, near the border with Kazhakstan. While that certainly is possible—the trade routes of central Eurasia have long been in operation—it seems difficult, if not impossible, to prove by just this particular entry.

Maketsu

Maketsu (眞毛津) was a seamstress sent over to Yamato from Baekje. She is hailed as the ancestor of the seamstresses of Kume. At that time it seems common to set up villages that specialized in particular goods and skills, and many of the stories of this time talk about the deliberate importation of expert crafters from the continent.

Clothing in particular we have a rather murky view of until we get more human-shaped haniwa in the 6th century, and even then it can be difficult to make out what is actually going on and what is exaggeration by the haniwa sculptures, but here we can see textual evidence of what we see later on, which is the influence of continental styles on the archipelago. Granted, prior to this they were probably in synch with at least what was going on in the southern tip of the peninsula, but I suspect that what Maketsu and people like her were bringing may have been a more Sinified aesthetic.

I should note that it mentions she was sent as “tribute”. It is unclear to me just how much choice that artisans like this had in their assignments, but my guess is that they didn’t have much. It has been a not-uncommon move across the globe for artisans to be forcibly taken and re-established elsewhere so that another group could acquire their intangible cultural properties. Of course, there are also examples where artisans were also enticed with lucrative offers of a comfortable living, and some may just have wanted to travel and explore the world, but given the way it is written and how people were enslaved, resettled, and sometimes sent to foreign courts, I suspect that there was very little choice involved here.

Iwa no Hime

We are told that Iwa no Hime (磐之媛) was the daughter of Katsuraki no Sotsuhiko. She would go on to become the queen of the sovereign Ōsazaki, aka Nintoku Tennō, and her son, Izaho Wake, would eventually follow him on the Yamato throne, becoming known as Ritchū Tennō. I wonder if this connection had something to do with the way that Sotsuhiko is treated in the narrative.

King Naemul of Silla

Naemul was the first historically attested sovereign of Silla in the 4th and very start of the 5th century. Naemul sent the future King Silseong to be a hostage at the Goguryeo court, and may have been the one to send Prince Misaheun to the Wa.

King Silseong of Silla

Silseong followed Naemul, despite the fact that Naemul had at least three sons: Nulji, Bokho, and Misaheun. In the first year of his reign, according to the Samguk Sagi, Prince Misaheun was sent to the Wa as an envoy, though this may have happened in the reign of Naemul, as attested to in the Samguk Yusa. Later he would send Prince Bokho to Goguryeo, and he married his daughter to the eldest of Naemul’s sons, Nulji. Eventually, though, he seems to have had a change of heart and attempted to have Nulji killed, but the plan would ultimately backfire.

King Nulji of Silla

After killing King Silseong in retaliation for Silseong’s attempted assassination of Nulji, one of the first things that King Nulji would do is to set about trying to get his brothers returned from the various courts at which they were being held hostage. This was eventually accomplished by the loyal courtier, Pak Jesang

Prince Bokho of Silla

Prince Bokho was sent by King Silseong as a hostage to the court of Goguryeo. He eventually escaped their custody with assistance from Pak Jesang.

Prince Misaheun of Silla

Prince Misaheun was a hostage at the Wa court. His eventual rescue is mentioned across multiple sources, with slight variations in the details, including the Nihon Shoki, the Samguk Sagi, the Samguk Yusa, and the Dongguk Tonggam. In the Nihon Shoki, Katsuraki no Sotsuhiko plays a prominent role in those events.

Pak Jesang

Pak Jesang was a loyal courtier of the Silla court. He offered to personally go and bring back King Nulji’s brothers, the Princes Bokho and Misaheun. Even today he is held up as a legendary example of loyalty, giving up everything, including his family and, eventually, his life for his lord.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua, and this is Episode 47: The Man who Might be King

There are certainly a lot of names that get thrown around in the Chronicles. Most of them only appear once, usually in a list telling us who begat whom, which usually looks like a rather blatant attempt to connect some high muckety-muck with the royal family or otherwise explain the origin of some person or group that was around in the 8th century. This is especially true of the eras we’ve been discussing, I’d say, probably because of the lack of good source material to draw from, among other things. Still, you occasionally get a recurring character here or there that keeps popping up and making an appearance.

Last episode we talked about one such supporting character, Takechi no Sukune, the first Prime Minister, or Oho-omi, who supposedly held his job through at least 5 different reigns, and who was involved in some of the more impactful parts of the narrative, even if he wasn’t the main character.

Now Takechi no Sukune isn’t the only name that keeps popping up again and again in the Chronicles for this time—though certainly he seems to be one of the most influential, not to mention long-lived. Unfortunately, just like the sovereigns he served, we cannot confirm anything about his actual existence. Was he an actual person? Or was he, perhaps, an amalgamation of individuals, perhaps all serving under the name or title of “Takechi”? I suspect that he was an important figure in the transition to the new dynasty—possibly someone referenced in various stories, and maybe he did provide some kind of connection back to the previous dynasty, but all of that is speculation.

At the same time, we have evidence of at least one individual from this time who, more likely than not, did exist. In fact, he’s got a better claim to actual historicity than do either Homuda Wake, the supposed sovereign of Yamato, or his prime minister Takechi no Sukune, since he unlike either of them, this person is directly referenced in the Baekje annals by name. Furthermore, despite not having as many entries in the Japanese chronicles as either of those other two, he seems intimately tied in to the royal lineage. On top of all of that we’ve mentioned him before, though just in passing. His name is Katsuraki Sotsu Hiko.

Now, Katsuragi is a place name, as well as the name of a prominent family group, which is quite likely related. It is located in the southwest corner of the Nara Basin, opposite the old capital at Miwa in modern Sakurai. I haven’t found anything that clearly states when it became a place of significance—or even if the place was named for the family or vice versa. Regardless, the family group claims a lineage going all the way back to the time of Iware Biko, though you may have some inkling just what kind of stock I put into all of that.

More importantly for our current narrative, the Katsuraki family are found in the lineage of Homuda Wake’s mother, Okinaga Tarashi Hime. Specifically they are mentioned as part of the lineage descending down to her from that ancient Silla Prince, Ame no Hiboko. So they are both tied to the royal family and to the royal family of Silla, though of course there is no evidence for this prince in the Silla annals, just in the Japanese chronicles. Still, that tie to the continent is going to be important, because it is in dealing with the continent—and in particular dealing with Silla, where Katsuraki no So-tsu-hiko will gain most of his notoriety.

Before we get to those stories, let me quickly touch on the rest of his name, though: Sotsu Hiko. It is an interesting name, in part because it would seem to mark this character as the lord or prince—Hiko—of some place called “So”, assuming that the “tsu” here is, indeed, that possessive marker we’ve seen and discussed before. In the Baekje annals his name is rendered as Sachihiko, which may simply be a transliteration error from the Japanese to the Korean and then back again. In Old Japanese these characters likely sounded even closer: probably something like So tu Bpiko, and “Sa ti Bpiko”.

So to start with, let’s go with the story that is at the core of the belief that So-tsu-hiko was, indeed, a real boy, and that is the excerpt that the Japanese Chroniclers included from the Baekje Annals for the year 382. Now in the hodgepodge of the Chronicles this event actually shows up during the reign of Okinaga Tarashi Hime, backdated by 120 years to 262, but given the rest of the contextual evidence we can fairly confidently put this incident at about 382, which is about 9 years before the events recorded on the stele of King Gwangaetto the Great. This is in the time of King Gusu—aka Geungusu—of Baekje, who had succeeded his father, King Chogo, in 375. In Silla this was still the reign of King Naemul, who had sent his envoys to the Jin court only a year earlier.

According to the Baekje records, the Wa were angered when Silla didn’t wait upon them—by which I assume they mean that they didn’t send them the expected payment-slash-bribe that they were expecting—and so the Wa sent a force to attack Silla, under the command of So-tsu-hiko. So-tsu-hiko had his forces ready to march on Silla, but Silla had a rather unusual plan of their own. Rather than readying an army to oppose him they decided to appeal to try a different approach, sending two beautiful Silla ladies to seduce him. Apparently this ploy worked, and So-tsu-hiko called off the attack on Silla, though that left him with a conundrum: He had troops in the field, and no doubt they were expecting some action.

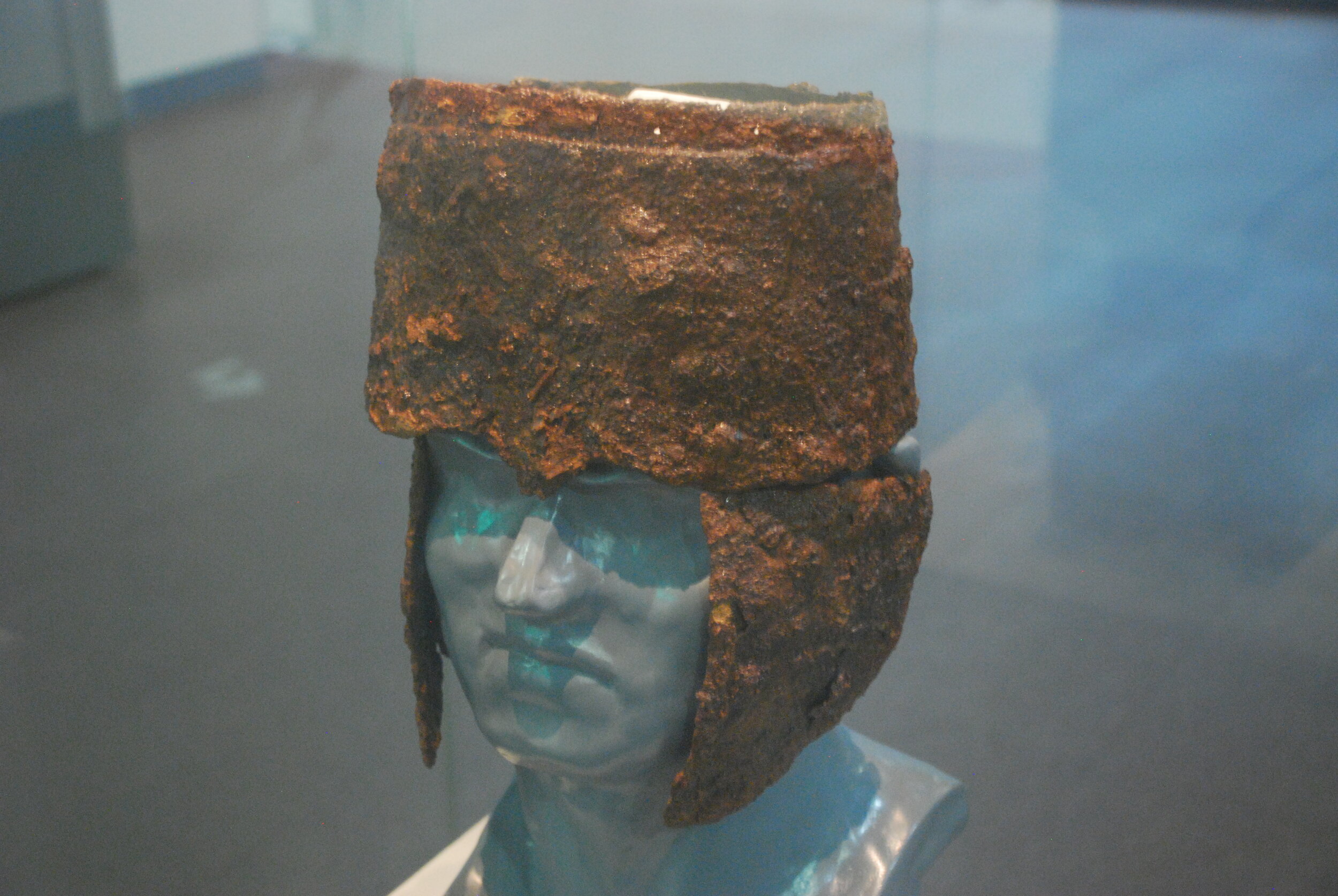

While we don’t know a lot about the military armies or bands or whatever they were at this time, certain things we can deduce from what we know about militaries around the world. One of those things is that, historically, you need to make sure your troops get properly rewarded, since they are putting their lives on the line. Even in conscript armies you need to keep morale up, and in this period I suspect that many of the soldiers fighting were probably doing so on a semi-voluntary basis, mainly because Yamato court didn’t quite seem to have the kind of authority to just force people off of their land to go fight and possibly die on their behalf. I doubt anyone at this time had true standing armies, though we are starting to see more weapons and armor—something that will become common burial goods, replacing the earlier bronze mirrors as high status grave goods.

Besides, it takes a lot of organization to keep soldiers fed, clothed, armed, and trained, and typically the resources to do that came from the booty acquired during the actual fighting. In later periods we would see this as land that could be given out to those warriors who had fought exceptionally well, while in this period it may have been more material goods, captured during the fighting.

Either way, these troops would need to be taken care of—to send them all the way to Silla, ready to fight, but then to balk at the last minute might have been a rather dangerous ploy for So-tsu-hiko. In all likelihood it he found it easier to simply redirect his forces, and so, instead of reprimanding Silla, the army marched into the lands of Kara, instead.

Of course, this was not exactly a subtle change in direction. The King of Kara, given in the Baekje Annals as Kwi-pon—though Aston gives his name as Si-Bpeum according to his reading of the Korean Tonggam—fled to Baekje due to So-tsu-hiko’s assaults. The King’s sister, Kwi-chon-chi, then went to the Great Wa—aka Yamato—and asked the sovereign there, Okinaga Tarashi Hime, for assistance, complaining about the assaults by So-tsu-hiko and his Wa troops. Well Tarashi Hime was quite livid to hear of this impertinence. Her orders to So-tsu-hiko had been clear, after all, and they had been all about reprimanding Silla, nothing to do with attacking Kara. And so she asked for the Baekje general, Mongna Keuncha, to go and sort things out. Mongna Keuncha, as you may recall from some episodes back, was one of the generals that had led troops as part of the Baekje-Wa alliance, and so here he is again, setting things right in Kara.

Mongna Keuncha appears to have been successful at stopping the assault on Kara, but he didn’t capture So-tsu-hiko, who remained at-large on the continent, presumably with those two Silla women to keep him company, though who knows if they had stuck with him through his defeat. Another account, for which, like a viral meme on social media, we aren’t given the actual source, claims that So-tsu-hiko went into hiding as soon as he learned that Tarashi Hime was upset with him.

That said, Sotsu Hiko had his own eyes and ears in the court. He seems to have had an in with one of the ladies at court, who still thought well of him, despite everything that had happened. After giving everything some time to blow over, he secretly sent her a message and asked her to feel out the mood in the court—specifically that of the sovereign. This court lady found a time to bend the ear of Tarashi Hime. She claimed to have had a dream about So-tsu-hiko. Well as soon as the lady in waiting mentioned his name, Tarashi Hime’s mood soured, and she loudly declaimed that should he ever show his face around Yamato again, she would have him killed.

And so no, things hadn’t blown over. Realizing that no pardon would be forthcoming, So-tsu-hiko headed off into a cave and died.

Which, of course, would seem to bring our story to a close. He was a general, he went to Silla, he was seduced into betraying his orders, attacked Kara, and then died, hiding in seclusion.

Except, of course, that isn’t at all where this ends. In fact, it is barely the beginning, and this is probably why the Chroniclers caveated that whole portion with “one source says” because I suspect even they were having some problem putting all of this together.

You see, Katsuraki So-tsu-hiko shows up—either by his full name or just as So-tsu-hiko, in stories from at least the adjusted year of 325 and then continuing for the next century and a half, scattered across three reigns. Of course, from what we can verify we can more reliably trace him in the historical record from about 325 to probably 418, and maybe even 426. For all of that, though, many of the stories about him seem to be retellings of the same incidents, just placed in different reigns, though with some of the actors changed. We’ve seen similar “repeated” stories in the Chronicles after all.

For example, in the 14th year of Homuda Wake’s reign—probably about 403 CE, right smack dab in the middle of the conflicts with Silla and Goguryeo--, we are given another story about So-tsu-hiko. In this case an envoy named Yutsuki—or possibly something like Kungweol, in modern Korean—attempted to travel from Baekje to Yamato to provide his allegiance. Word may have been sent with an envoy earlier that same year, or perhaps the year prior. The Baekje annals in the Samguk Sagi note that Baekje had sent an envoy to Wa to seek out large pearls, while the Japanese chronicles mention a seamstress named Maketsu who was sent over—possibly as part of the ongoing exchange surrounding the, shall we say, residency of Crown Prince Jeonji of Baekje at the Yamato court. To help Yutsuki make the journey, So-tsu-hiko was sent out to see them safely from Kara at the end of the Korean peninsula, over to Yamato, but after he left, the court heard nothing.

Of course, in this age before modern communication, it is little wonder that nobody heard anything back immediately. All sorts of pitfalls could waylay a journey, and who knew how long it would take on the other side before anyone heard anything back. In this case, though, it was rather excessive, as three years went by and still nobody had showed up at the Yamato court. And so they sent two generals out to find out what happened. Convinced that Silla had interfered and was holding them, the troops made there way to Silla and, low and behold, Silla was indeed keeping So-tsu-hiko and Yutsuki hostage. Under the threat of the Wa forces, or so we are led to believe, Silla admitted to kidnapping them and allowed them to return with the Wa forces.

Now some see in this story a retelling of the earlier So-tsu-hiko story, possibly mixed with something like the early stories of the Baekje ambassadors from the supposed first meeting of Baekje and Wa, who were also waylaid by Silla and, in that case, forced to bring Silla envoys along with them to the Yamato court. In both casesHere, you have So-tsu-hiko going to the continent and someone else having to go after him. In this story, though, he is treated as more of a victim, rather than a rogue general. And in all of these instances it is Silla who somehow detains him or causes him to stray from his mission.

Of course, this could just be a common theme in pen-insular relations—Silla may have regularly looked to intercept Wa and Baekje ships, and vice versa. But there are a few of these kinds of accounts scattered about.

Unfortunately, there isn’t too much too corroborate this in the Korean sources. The Samguk Sagi does have the Wa attacking the peninsula around 405 CE, but according to Silla they were repelled. Then there were two attacks in 407 where they kidnapped 100 people and took them back with them. But whether any of this correlates to the other stories is impossible to say for certain.

Now as to why one story has So-tsu-Hiko as the villain, disobeying the court, and the other paints him as a victim of Silla’s treachery may have to do with the different sources that the stories were coming from, as well as what we are told afterwards. You see, Katsuraki no So-tsu-hiko had a daughter named Iwa no Hime, who would wind up marrying Ohosazaki, the successor to Homuda Wake. She would give birth to one of the future sovereigns, Izaho no Wake. This, by extension makes So-tsu-hiko the ancestor of several generations of sovereigns in the Middle Dynasty, as well as the current lineage, at least according to the Chronicles.

This is interesting for a few reasons, beyond perhaps the obvious. I mean, let’s face it, everyone was trying to tie themselves to the royal lineage, so I don’t think that his placement there is all that big of a shock—if you were a major family and you didn’t claim some tie in with the court then come on, you aren’t even trying, and there were some big names that claimed descent from So-tsu-hiko.

Beyond that, though, it wasn’t just that one of his daughters was married to the sovereign, but rather that she was considered a queen. You see, as we’ve discussed before, there are multiple women who are brought into the royal family as wives of the sovereign, but most do not become the queen, and so their offspring are not considered to be in line for the Yamato throne. To be considered eligible to be a queen, and thus for one’s offspring and descendants to be considered eligible to inherit the throne, a woman had to be of royal blood herself.

Now, of course, technically Iwa no Hime is of royal blood, as is So-tsu-hiko. The Chroniclers saw to that, making sure to connect So-tsu-hiko to Takechi no Sukune, but as we discussed in the last episode on Takechi no Sukune, there are a few things that call this lineage into question, not the least being their disparate titles.

Of course, this wouldn’t be the first questionable lineage in the sources, especially for women who would become the queens and mothers of the official sovereigns. However, in this case, she is the daughter of a supposed subject, rather than being the daughter of some lord outside of the Yamato court. So, unlike with those others for whom a royal inheritance may have been manufactured, here we see no obvious political benefit to the royal line for her to be considered as a Queen, let alone for her children to be considered legitimate claimants. Dr. Cornelius J. Kiley discussed this back in 1973 in an article entitled “State and Dynasty in Archaic Yamato”, published in the Journal of Asian Studies. There he discusses a few other points about the succession, but regarding So-tsu-hiko in particular he points out that the stories have him defying the orders of the Yamato sovereign, and later some of his descendants would go on to found the powerful Soga clan, which dominated court politics in the 6th and early 7th centuries. And of course the Soga’s power seems to have been partly based in their association with Buddhism and the continent, which we will see in a bit coming over from the Korean peninsula as well.

Dr. Kiley isn’t the only one to have noticed all of this, and there is some thought that the truth may be that So-tsu-hiko was not actually a vassal of the Yamato court, but rather another sovereign or independent Wa lord who was heavily involved in the activities of the peninsula. Here it is suggested that So-tsu-hiko, wherever he was based, was perhaps in alliance with Yamato, but likely had his own powerful territory or kingdom, and it may be that more than a few of the actions ascribed to figures such as Homuda Wake or the ambiguous “King of Wa” may have actually been referencing him, or some similarly independent figure. We can’t know for certain of course, but we do know that there were other powerful figures—perhaps even rival courts—across the archipelago, given the number of large, kingly tombs that we see outside of the immediate geographical base of the Yamato court.

And so it may be that So-tsu-hiko was his own kind of sovereign—a king in his own right, as it were. He may have been allied with Yamato, and it is even possible that, as an independent ruler of some part of the archipelago or the southern peninsula, he was supporting a larger confederation of Wa countries. Of course, this totally goes against the narrative of the Yamato court, where the rule of the Heavenly Descendant was just a natural consequence of their divine nature and the fact that the kami had gifted the archipelago to them. Even early stories of conquest are treated more like inspection tours, with the odd outsider or resistance from uncivilized barbarians, rebels, and bandits, but no real talk of any other sovereigns. This is especially true in dealings with the continent, where the official story continues to push a narrative of conquest and subjugation by Yamato—a narrative that is not exactly backed up by the other evidence we have available to us.

So was So-tsu-hiko an independent king in his own right, possibly even the true power behind the early Baekje-Wa alliance? Or was he just another court noble, who was then entrusted with great responsibilities on the continent? Or was it something in between? Could this be why we have some stories where he seems rebellious and antagonistic, and others where he is shown in a more positive light, the Chroniclers working from stories from different parts of the archipelago and from different dynastic eras?.

These are the things I urge you to keep in mind as we read further stories about So-tsu-hikothese stories and try to piece together what is happening. That said, let’s get into those stories, and what they tell us.

Now, of only passing interest to us, perhaps, is an account from the 41st year of the reign of Ohosazaki—a year that probably didn’t exist as Ohosazaki was, most likely, not on the throne for that many years to begin with, but they still had to make up all that time since they were condensing the entire 3rd and 4th centuries into only three reigns.

Now in the account of that year we are told that the grandson of the King of Baekje was rather disrespectful towards the Wa envoy, Ki no Tsuno no Sukune, and he was delivered up to So-tsu-hiko to be brought back to Yamato as a form of punishment.

Again, this story has some eerie parallels with another.

There was another act of disrespect from Baekje during Homuda Wake’s reign, where Ki no Tsuno was also sent to the Baekje court to handle the matter. In that case it was king Jinsa of Baekje, whereas the later story focused on a different king, but there are enough similarities to make you wonder if they aren’t just different stories of the same event. So this could be taking place any time around the end of the fourth or first quarter of the 5th century.

And where this intersects with us is that, in the later telling, So-tsu-hiko appears to have been on hand at the Baekje court, or at least in close enough proximity that he could come and take charge of the young princeling and escort him across the straits to Yamato, where he was basically kept as a hostage as penance for his insulting behavior.

Thus, once again we see So-tsu-hiko in a role of essentially escort. Whether it was the young Baekje prince being sent to Yamato as a punishment, or envoys like Yutsuki being brought to pay tribute, So-tsu-hiko was the one who was helping them from the peninsula to the archipelago, and facilitating their journey across the ocean.

Now I’ve tried to save the best for last. It is, in my opinion, the most dramatic account that So-tsu-hiko is involved with, and that is the escape of Prince Misaheun of Silla from the Yamato court.

Now back in Episode 45 we mentioned that Prince Misaheun was sent to the Wa in the year 402, by the continental reckoning, which was also during the events inscribed on the Gwangaetto Stele. Silla claims he went as a peaceful envoy, but the Wa held onto him as a hostage, refusing to let him return home. It is a tale that is found not only in the Samguk Sagi, which says he was sent by his uncle, King Silseong, but it is also found in the more fantastical accounts of the Samguk Yusa, where blame for his departure was put on King Naemul. I tend to lean towards the Samguk Yusa story on this one, given a variety of factors. The Nihon Shoki, as usual, plays fast and loose with dates, and without going into too much details, let’s just say the Japanese chroniclers put this story during Okinaga Tarashi Hime’s reign because it fit right into the stories of various raids and military exploits that they were lumping together. Regardless, Prince Misaheun becoming a hostage of the Wa was a big deal, no matter when it happened. Although, had King Silseong had his way, it likely would have become a non-issue altogether.

We’ve already talked about how King Silseong came to the throne of Silla, having spent ten years as a hostage in the Goguryeo court before succeeding his brother, King Naemul, Misaheun’s father. Upon coming to the throne, he almost immediately sent Misaheun as a hostage to the Wa—though perhaps that had already happened during the Wa invasion mentioned on the stele during his brother’s reign. Ten years after taking the throne, Silseong would send another of his nephews, Prince Bokho, to the Goguyreo court, to be a hostage there, much as Silseong himself had been. You can see in both of these examples a trend: Silseong wass getting his brother’s children, future rivals for the throne, out of the way.

And sure enough, only five years later, Silseong was starting to worry. He had taken the throne in the first place under the pretense that none of his brother’s heirs were old enough at the time, but now his eldest nephew, the eldest, Nulchi, was getting on in years. Though Nulchi was married to Silseong’s own daughter—proving that it wasn’t just the Wa who liked to keep it in the family, so to speak—about fifteen or sixteen years into his reign, Silseonghe decided that he would do something about Prince Nulchi—permanently. The stories claim that he hired a man from Goguryeo—an outsider, an one whom he probably had contacted through his network within the Goguryeo court. He hired this ancient hitman to kill Prince Nulchi, and arranged for the two of them to meet on the road.

As you might guess, things didn’t go according to plan. Apparently the hired sword had a soul, and when he saw Nulchi on the road he was struck by his appearance—the elegant air of a prince of the blood. Rather than kill the Prince, the would-be assassin told him how he had been hired by his uncle, the king, to kill him, and then he returned to Goguryeo. Nulchi was incensed, and rightly so. Taking matters into his own hands the Silla annals tell us that he found his uncle, King Silseong, and killed him and took the throne for himself. The Samguk Yusa gives slightly different details than the Samguk Sagi, claiming that it was group of soldiers that were sent after Nulchi, and that when they met him they switched sides and killed King Silseong instead, installing Nulchi on the throne.

Once he was on the throne, King Nulchi immediately decided to get the gang back together, and he started looking for a way to bring his two brothers back to Silla. Into this stepped a man of Silla known as Pak Jesang. Much like Takechi no Sukune and Katsuragi no So-tsu-hiko, Pak Jesang is one of those fascinating characters who lives in the margins of the stories of the rulers of these ancient countries. Much of what we know about him comes from this story – which, according to Samguk Sagi, along with the Dongguk Tonggam, took place around 418, while the Samguk Yusa gives the date as 426, and most of the details come from the Samguk Yusa and the Nihon Shoki, with some corroboration coming from Aston’s notes on the Tonggam.

Now Nulchi was grieving for his brothers. Neither Goguryeo nor Yamato were ready to just give up their royal hostages, and so Silla needed a wise and brave man to help them hatch a plan. They found such a man in Pak Jesang, the form of the magistrate of Sapna county, and his name was Pak Jesang. Pak gladly accepted the task from his king, and after taking his leave of the court he disguised himself and headed north, to Goguryeo, to the capital at Gungnae—modern Ji’an, where Gwangaetto the Great was buried. There he found out where Prince Bokho – the Goguryeo hostage – was staying, and found a time to talk with him in secret.

Here it may be helpful to understand that being a royal hostage wasn’t quite the same as being a prisoner. Though the prince was unable to leave, it is quite likely that he was being kept in a manner befitting his station, and he would regularly attend the King’s court. He had the opportunity to meet with the members of the court and the people around him and get to know them. He just wasn’t allowed to leave.

Unfortunately, the actual escape from Gungnae—which only sounds like a Snake Plissken flick—isn’t recorded in any great detail. What we do know is that Pak Jesang had a plan, but that plan apparently consisted of the Prince pretending to be sick for a few days, and then finally running off to meet at Koseong, on the coast, where Pak Jesang would have a getaway boat ready. Seems easy enough… except when you realize that the coast would have been well over 300 kilometers away. I hope he had a horse.

Regardless, it seems to have worked, in part because of the good friends that Prince Bokho had made, particularly amongst the guards. When they king found out he ordered his guards to chase him down, but they used headless arrows when they fired at him, and deliberately missed, since he had been such a good friend to all of them—or so the stories go.

When Prince Bokho made it back to Silla, his brother, King Nulchi, was overjoyed, but there was still one more prisoner left—Misaheun, hostage of the Wa. Pak Jesang left on that voyage so quickly he didn’t even stop to say goodbye to his wife, who ran after him, only to see his ship already departing the shore.

Now when Jesang made it to the islands of the Wa where they were holding Prince Misaheun hostage, here’s where we get the Japanese Chroniclers’ perspective on things as well. The Chronicles claim that Silla sent three envoys as part of a tribute mission, none of whom had names resembling Pak Jesang. In the Samguk Yusa we are told that Pak made it to the Wa court by claiming that he was running away from Silla, since the King there had killed his father and brothers without a legitimate reason. Apparently this was believable, and the Wa ruler provided him a place to stay.

As he was staying there, he made friends with Prince Misaheun, and the two of them began heading down to the seashore and bringing back their catch each morning to the Wa sovereign. They kept this up until one day, the fog rolled in, and Pak Jesang saw their chance. He had the Prince taken away by a Silla boatman, and then he went back to the Prince’s house to buy some time. When the Wa came looking for Misaheun to check on him, Pak Jesang told them that he was feeling tired from hunting the previous day, so he was resting. They came again at noon to ask after him, and by then they discovered that Prince Misaheun had fled.

The ruler of the Wa was wroth and ordered his men to go in pursuit, but it was to no avail—the Prince was long gone. Returning back to the court he sought out Pak Jesang and poured out his rage on him, since he had claimed to become a vassal of the Wa king. Pak Jesang, however, now defiantly claimed that he was a man of Silla, through and through, and even as they tortured him, standing him up on a red hot iron, he would not say anything but that he was a vassal of the King of Silla. Finally, realizing they would get nothing out of him, they hung Pak Jesang on Kishima—Ki island.

The story in the Nihon Shoki is similar, but definitely without the pro-Silla angle to it. There, Prince Misaheun beseeches the sovereign to let him go, claiming that the envoys told him that since he’d been away for so long, the King of Silla had confiscated his wife and family and had them enslaved. He asked to go back to Silla to find out if this was true.

The sovereign gave him leave to go, and here is where our friend, Katsuragi So-tsu-hiko, re-enters the narrative. As we already demonstrated, he was the go-to guy for people traveling from or to Yamato. Together they all reached Tsushima together—So-tsu-hiko, Prince Misaheun, and the three Silla envoys, along with whatever sailors and soldiers were sent along as well. They then stayed the night at the harbour of Sabi no Umi.

It was here that the envoys found the chance they had been waiting for. They put Prince Misaheun on a boat that they had arranged to meet them and they sent him back to Silla. In his place, they created a dummy made of straw, which they put in Misaheun’s berth on the ship, and made it seem like he was ill. So-tsu-hiko was worried about his health, however, and sent men to check on him, and help nurse him back to health, but of course, they discovered the ruse.

Angry and upset at being deceived, So-tsu-hiko had the three envoys placed in a cage and then burned them all alive. He then proceeded on with his ship and his men and attacked Silla, taking the castle of Chora, and capturing and enslaving numerous people whom he brought back to Yamato. These were the ancestors of several villages and families. He never did catch up with Misaheun, however, who made it safely back home.

There is one more telling, somewhere in between these two, which comes from the Dongguk Tonggam, and it is provided by Aston in his footnotes to the Nihon Shoki. As with the Samguk Yusa, it claims that Pak Jesang was the one who went to rescue Misaheun, but in this story he went to the trouble of actually having his own family and that of Prince Misaheun imprisoned so that when the Wa checked his story they would see it was true. Indeed, the Wa believed that both Misaheun and Pak Jesang were rebels, and so when they decided to send an army to attack Silla, they enlisted both of them as guides. The Wa generals were plotting each day on how to get in and take back the families of Prince Misaheun and Pak Jesang, but meanwhile, the Prince and Jesang were spending a little time each day in a separate boat, fishing, where they could discuss things.

One day, everything being arranged, when they went out on their excursion, Pak Jesang had Prince Misaheun taken in another boat back to Silla, while he stayed behind. He stayed out as long as he could, all by himself in the boat, until he was sure Misaheun was far away.

As soon as the Wa learned that Misaheun had escaped, they bound Pak Jesang and attempted to pursue Prince MIsaheun, but mist and darkness meant that they could not catch up. The lord of the Wa was enraged and threw Pak JChesang into prison. He interrogated him, asking him why he would help Prince Misaheun to escape, and, as in the Samguk Yusa, Pak Jesang simply stated that he was a vassal of the King of Silla. They tortured him numerous times, but he would not stray from his story. Finally, he was burned to death.

Though slightly different, we can see here three stories that are clearly about the same events. The actual names are a bit different, due to the problems of transliteration and even changes in the languages over time, though I have tried to standardize them here. Still, there are enough similarities that we can make out the general picture.

Now there is one more reference to So-tsu-hiko that I want to bring up, and that comes from the Man’yoshu. I can’t recall if we’ve talked about this, but the Man’yoshu is the oldest anthology of native Japanese poetry. While, yes, many poems exist in the chronicles, the Man’yoshu was written specifically for poetry, and it not only contains many poems that are said to be much older than the work itself, which was compiled around the same time as the Chronicles, in the 8th century, but it specifically made an effort to translate the sounds of Japanese, using Chinese characters.

Anyway, that work deserves an episode of its own, but for now I want to talk about just one poem that is found in that work, and it goes something like this:

Katsuraki no So-tsu-hiko ma-yumi araki ni mo;

Tanome ya kimi ga wa ga na norikenu

I’m not sure I can quite do this poem justice from a translation standpoint, but based on what others have said, it appears to be equating the strong, unfinished wood bow of Katsuraki no So-tsu-hiko with the act of telling someone—or possibly asking for—a woman’s name. This was a rather intimate act, as most women’s names were private, and typically only known to the family and to a prospective husband.

Because of the subject matter and the fact that it references So-tsu-hiko, some have attributed this poem to So-tsu-hiko’s daughter, Iwa no Hime. Of course, authorship is rather difficult to truly ascertain, but it does at least tell us that So-tsu-hiko was well enough known that his name appears in yet another source, even if just a fleeting reference.

We also can get a sense that he was more than just an escort. The reference to his bow being made of raw wood certainly suggests that people assumed he had a warrior’s aspect, and who knows what stories were being told that just aren’t around anymore?

Whatever else may have been floating around out there about So-tsu-hiko, this is what we have. We don’t even have a good story about his death, beyond that one which claims he killed himself because he couldn’t come back to the court of Okinaga Tarashi Hime, but we already covered how he was apparently active after her, though of course, who can really be sure of any of these things, particularly if the reigns overlapped in some fashion, as opposed to the strictly serial pattern of inheritance that the Chronicles put forth?

We do have a possible candidate for So-tsu-hiko’s final resting place, though even that is suspect. There is nothing mentioned, of course, in th e Chronicles, but there are some traditions claiming that he is buried at Muromiyayama Kofun, in Gose City. Of course this might be a bit awkward, as that is also said to be the burial place of Takechi no Sukune, and we covered it last episode. I doubt both of them are buried there, and it is just as likely that it is neither of them, but it’s interesting that both of these “recurring characters” in the Chronicles have these parallels in death as well as in life..

So that’s the story of Katsuraki no So-tsu-hiko. I hope you enjoyed it. Next episode we’ll continue, and hopefully wrap up the life of Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, and maybe even get into the cult

References

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Kim, P., & Shultz, E. J. (2013). The 'Silla annals' of the 'Samguk Sagi'. Gyeonggi-do: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

太田蓉子. (2020)「葛城」を詠んだ万葉の歌. http://www.baika.ac.jp/~ichinose/o/20211125ota.pdf

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Iryŏn, ., Ha, T. H., & Mintz, G. K. (2004). Samguk yusa: Legends and history of the three kingdoms of ancient Korea. Seoul: Yonsei University Press

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Kiley, C. (1973). State and Dynasty in Archaic Yamato. The Journal of Asian Studies, 33(1), 25-49. doi:10.2307/2052884

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1