Previous Episodes

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

This episode we cover the life of Takechi no Sukune, whom we’ve partially covered in past episodes, but this episode we take a look at his whole life, including records of his actions during the reign of Homuda Wake. There is a lot of discussion of different reigns, so I’ll try to lay out some of what is going on with each one. This might help give an idea of what we are seeing, but there are still a lot of questions and supposition in all of this:

Iribiko Dynasty

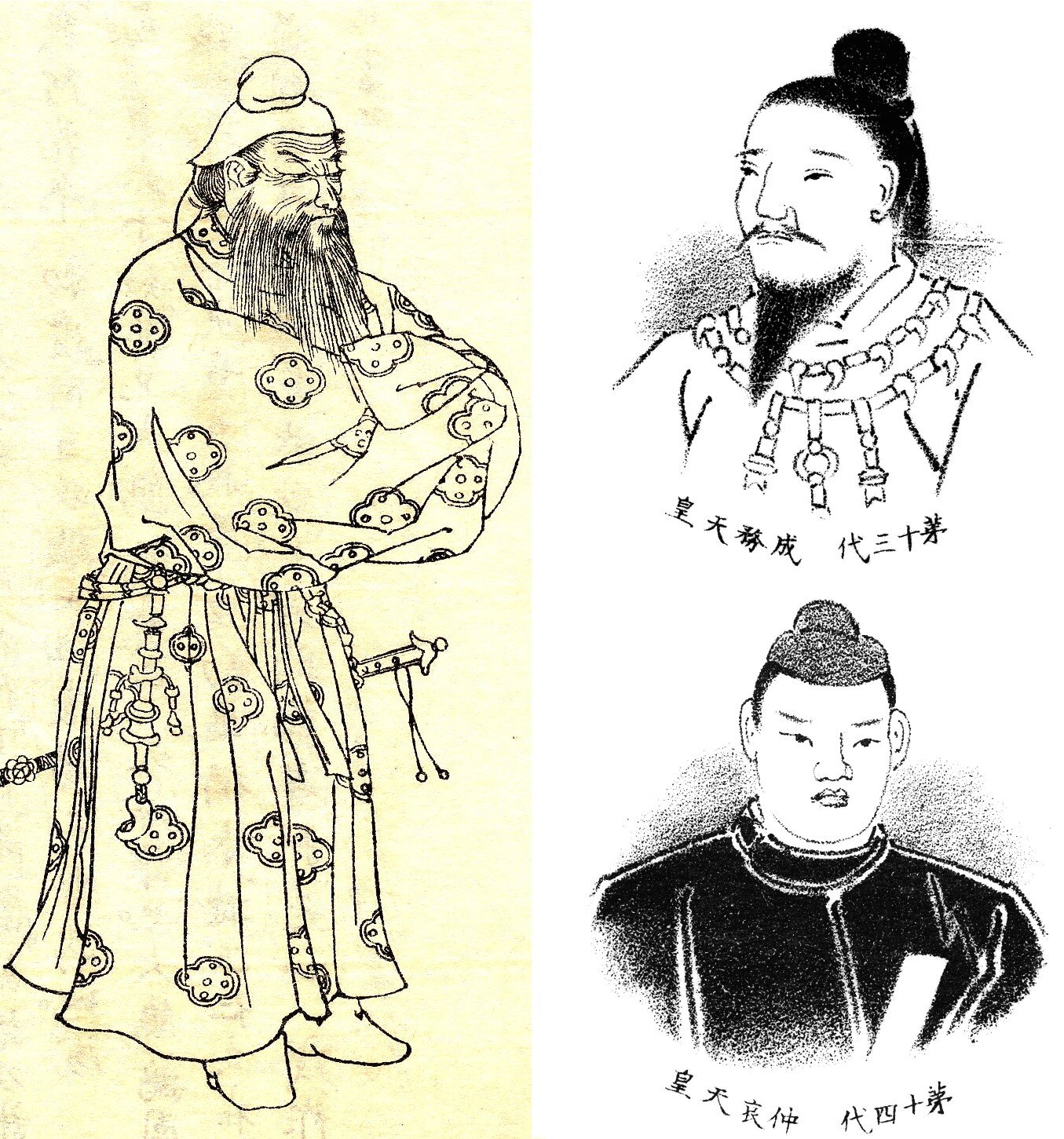

Mimaki Iribiko

Nominally the “first” dynasty of Yamato (despite the 10 reigns before), and contemporary with Yamato Totohi Momoso Hime, who might be “Himiko” by some estimations. She is buried in Hashihaka kofun, which dates from the 3rd century.

Ikume Iribiko

Mimaki Iribiko’s successor. This reign, which likely was in the later 3rd century, assuming Mimaki Iribiko’s reign ended somewhere near the time Hashihaka Kofun was built. During this period, there is early connection to the continent, and many of the traditions—sumō and the situating of Ise Shrine—that are placed in this reign.

Theoretically both Waka Tarashi Hiko and Takechi were born during this reign, it would seem, though it is likely that any direct connection between the Iribiko and Tarashi dynasty is fiction to try to connect these ancient stories together.

Tarashi Dynasty

Ōtarashi Hiko

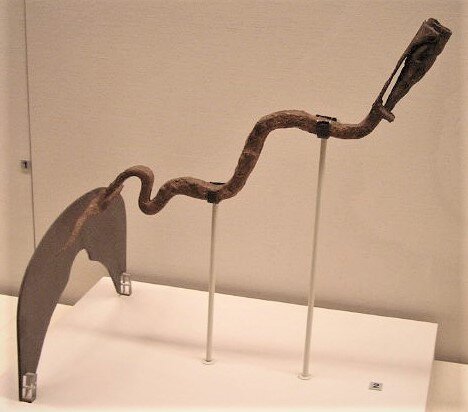

The first of the “Tarashi” dynasty. During Ōtarashi Hiko’s reign we see the “conquest” of much of the archipelago, including subduing the Kumaso in the south and the Emishi in the north, along with the occasional Tsuchigumo. It was during this reign that Takechi first starts to take on official duties. His charting of the East sets the stage for Yamato Takeru’s later campaign, during the same reign.

If this was really the reign that introduced Takechi, then one would have to assume that, given what we know about other reigns, it should probably be assumed to be somewhere in the mid-4th century.

Waka Tarashi Hiko

Despite a relatively long reign, very little is actually written about Waka Tarashi Hiko’s reign. He is said to have reigned well, but when he dies, the throne passes to his nephew, rather than to a son.

Tarashi Naka tsu Hiko

In comparison to the previous sovereigns, his reign was amazingly short—only 9 years. Despite that he still gets more written about him than Waka Tarashi Hiko. During this reign, we first meet Okinaga Tarashi Hime and Takechi no Sukune is clearly helping out with some of the ritual components.

Okinaga Tarashi Hime

Known for her raids against the peninsula, Takechi no Sukune seems to be her partner in her campaigns on the peninsula and in the archipelago. Later, Takechi is seen accompanying the young prince, Homuda Wake. Based on the connections with Baekje, this reign would need to have been in the later 4th century.

Many people have suggested that Tarashi Hime is completely fictional. She is definitely used as a stand-in for the Himiko of the Wei Chronicles.

Middle Dynasty

Homuda Wake

The first reign of the Middle Dynasty. He is probably the sovereign at the end of the 4th century and into the 5th century, though some doubt his existence as well. This is the last “reliable” reign where we see Takechi no Sukune.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is episode 46: I Stan Takechi no Sukune

Well, we’re back and we are still talking about the reign of Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou. Last episode we talked about incidents recorded on the stele of Gwangaetto the Great, which provide some important contemporary context for everything going on both on the peninsula and the archipelago at this time. These next couple episodes we’ll turn back to the Chronicles for most of our information, and we’ll look at some of the so-call “supporting” characters, those outside of the royal line, that are now starting to play larger and larger roles. And we’ll start with someone whom we already talked about in a previous episode, but whose exploits continue through the reign of Homuda Wake, and that is the legendary Takechi no Sukune. Now, I started this episode with the idea that we would just quickly cover a few things from Takechi no Sukune during the reign of Homuda Wake, but the more I started to get into the material the more I realized that I really want to do something of a deep dive. And I know we’ve talked about Takechi in the past, but I don’t think that did him justice.

I am finding that, the more I learn about him, the more fascinated I am about this character, in part because, before undertaking this project, I didn’t even know he existed. Or at least that stories about him existed—we can’t really say much of anything for the existence of any particular individual in the Chronicles, really, until we have corroborating sources and unfortunately I don’t know of any source that can corroborate the existence of this character—he exists purely in chronicles and related stories, from what I can tell.

And yet, I can’t shake this feeling that he is actually rather important to trying to understand some ground truth to all of this.

Now you may recall Takechi no Sukune—also known as Take-uchi no Sukune—from when we talked about the reign of Homuda Wake’s mother, Okinaga Tarashi Hime, aka Jinguu Tennou. Now during Homuda Wake’s reign, Takechi no Sukune continued on in his role as Prime-minister-for-life.

His exploits, of course, begin well before this period, and even before that of Okinaga Tarashi Hime, Takechi no Sukune supposedly came into the world the same year as Homuda Wake’s great-uncle, the sovereign Waka Tarashi Hiko aka Seimu Tennou, which would put his birth during the reign of Ikume Iribiko, or Suinin Tenno. That’s about five reigns back from where we are now, and probably in the latter half of the 3rd century, assuming the Iribiko dynasty fills in for the time around Queen Himiko’s reign. And so the Chronicles already have him living well over a century at this point in the narrative, surviving several contemporary sovereigns and would-be sovereigns, and providing a rather storied career in the process. Of course, despite everything he accomplished, the chronicles aren’t really about him, so they still treat him like a background character, kind of like Rex in the Clone Wars, or even Wedge in the original trilogy—though in this case we may be more in R2D2 territory, given the scope of his involvement. Sure, the story may be focused on members of a particular dynasty, but when you really look, he always seems to be there at those critical moments.

As I said before, Takechi no Sukune had quite the life. During his youth, he purportedly marched out to the east, to explore and open up those lands.Of course, Yamato Takeru took most of the credit for all of that, his own legends far outstripping, and possibly even replacing, those of young Takechi. Furthermore, despite his youth, he displayed uncommon loyalty and good sense from the get-go. For instance, there was that time that Oho Tarashi Hiko threw a party so grand that all of the court officials were basically secluded in a drunken bender for several days. All, that is, except for Takechi no Sukune and Prince Waka Tarashi Hiko, who stood guard over the palace to make sure that none of the court’s enemies decided that this was a good time to get up to some shenanigans.

For his loyalty and good sense, Oho Tarashi Hiko made him Oho-Omi—the Prime Minister, and the next several sovereigns also confirmed him in this role. This would mean that he was not only involved in administering the affairs of Yamato, but also he would be heavily involved in the rituals as well. This shouldn’t be at all surprising since the two went hand in hand—in fact, you can’t really separate the two, and this would remain the case for much of Japanese history. Thus, when the kami contacted Tarashi Naka tsu Hiko and Okinaga Tarashi Hime and commanded them to invade the Korean peninsula, he was there, assisting with the rituals, helping to cover up Naka tsu Hiko’s death, and eventually supporting Tarashi Hime as she sailed forth. Later, during the formation of the Wa-Baekje alliance, we once again find Takechi no Sukune at the wheel, delegating who would be the ones to represent Yamato in negotiations.

Beyond helping to direct overseas negotations, he also seems to have had quite the hand in Homuda Wake’s own upbringing. Not only did he help keep him safe as a child, but he later took the young Prince around Lake Oumi, and to Tsuruga Bay, where Homuda Wake exchanged names with the kami, which we discussed back in episode 41.

And so, other than the incredible lifespan that it would seem to imply, it should be no surprise that Takechi no Sukune continued to be deeply involved with government affairs during the reign of Homuda Wake, as well. For example, given increased traffic with the peninsula, there were more and more people coming to the islands from elsewhere. Most of these visitors are identified with either Baekje, Silla, or Kara, though in this reign we do start to see some discussion of Goguryeo as well—we’ll spend a lot of time on everything going on here next episode, as there is a lot happening, especially at the end of the 4th century and into the early 5th. For whatever reason that people are coming—whether by choice, seeking greater opportunities, or fleeing war and conflict, or possibly even as slaves, captured in raids—the Chronicles give Takechi no Sukune command of these immigrants, who are immediately put to work building ponds.

As a quick reminder, building ponds was actually something that was quite important. Up to this point it has largely been sovereigns and royal princes who were building ponds, and so this isn’t just about digging ditches somewhere. These are effectively community hydrological works, and seem to have been important irrigation projects. The pools themselves are named things like the “Baekje Pond” and the “Kara Pond”, seemingly referencing the labor used in their construction. Though it is odd that the Baekje Pond, which is mentioned in the Kojiki, was apparently built by immigrants from Silla. Meanwhile, the Kara pond, mentioned in the Nihon Shoki as being made specifically under Takechi no Sukune’s supervision, with labor by people from Baekje, Silla, Goguryeo, and, interestingly, Nimna, aka Imna or Mimana. Of course, most of those aren’t “Kara” or “Kaya” as we know it, though “Kara” would eventually become a general term for anything from the peninsula and even from the continent.

So here we see that Takechi no Sukune continued to have significant influence in the court. He had a hand in just about everything. But it wasn’t all just administration of the state, and there is a story in this reign that I think talks to the personal influence he had with the sovereign and the royal family.

The story revolves, as many of them do, around a woman. Her name was Kaminaga Hime, and she was the daughter of the Muragata no Kimi no Ushimoroi in the land of Himuka, on the eastern shores of Kyushu, and news of her exceeding beauty had reached the ears of the Yamato court. Now we are told that Ushimoroi had long served Yamato, but he was getting on in years and thinking of retiring. As he did so, he offered his daughter’s hand to the sovereign—which would seem to be another example of those marriage politics we’ve seen used to create bonds between various parts of the archipelago. Ushimoroi’s title of “Kimi” would seem to imply that he was some kind of local ruler, possibly over an independent country or region. So this would have been an offer with some political weight beyond just the fact that she was a beautiful woman. Homuda Wake was greatly intrigued, and so he sent for her to come and to become one of his many wives at the palace.

Now neither communication nor travel were instantaneous back in those days, and so it was that six months went by. Homuda Wake went on with his life, and one day he and his retinue had traveled to Awaji Island, on the Seto Inland Sea, to take part in some hunting, when he spided something rather odd. Looking out to sea, towards the Harima coastline, and he saw what appeared to a herd of stags swimming towards him in the water. They eventually stopped at the harbor of Kako in Harima, a little ways east from the modern city of Himeji. Intrigued by what he had seen, Homuda Wake sent a messenger over to Kako to find out what was happening. It turned out that what they had seen, off in the distance, were actually the boats accompanying Kaminaga Hime on her journey to Yamato. The men rowing the boats had all donned deerskins, with the horns still attached, apparently as part of some ceremonial garment.

And if you would, just take a moment to imagine what that must have been like as they cut through the water.. From far away, it very much may have looked like a herd of stags, all in a line, swimming through the water—and deer are known to swim between islands, so that wouldn’t have been so strange, but for them to be lined up in two neat rows, all with impressive racks, well, it is no wonder that Homuda Wake sent someone over to figure out just what was going on.

It seems that Kaminaga Hime wasn’t playing around. She was coming in all of the glory of her station, and nobody was going to question who she was or the power of her people.

When the impressive, antler-clad retinue finally made landfall, they were greeted by the court. The Chronicles then tell us that immediately one of the royal princes, Ohosazaki, one of Homuda Wake’s many sons, became awestruck by her beauty, and fell immediately in love.

Of course, lovestruck though he might have been, the prince had a problem, becuase she had come to marry his father, not him. Perhaps if it had been anyone else, he could have easily claimed some prerogative, but it would probably be a bit awkward to ask his dad to just stand aside.

And so who did Ohosazaki turn to in order to help him out? You guessed it, the trusted advisor and prime minister, Takechi no Sukune.

I imagine the scene playing out as if this were some anime—or possibly even a Shakespearean play, the tropes surrounding lovestruck youth are plenty old. Anyway, I imagine Ohosazaki, his heart beating with his young crush, storming into Takechi no Sukune’s quarters and swooning all over the furniture while pouring out his grief at his hopeless case, Takechi, of course, just patiently taking it all in and consoling the young Prince. Of course, the Chronicles aren’t nearly so dramatic and simply note that Ohosazaki asked Takechi no Sukune to intercede on his behalf in hopes that he could make Kaminaga Hime his wife.

Well, if there was anyone who could help the young prince, it was Takechi no Sukune. And so he found an appropriate time to bend the ear of Homuda Wake, probably taking him aside and letting him know about his son’s longing. Of course, had Ohosazaki asked for her hand directly, that might have been considered improper. However, Homuda Wake had several wives at this point, and for all of Kaminaga Hime’s connections, it was unlikely that she would take the place of his primary queen..

And so, with Takechi no Sukune’s help, Homuda Wake could make it look like giving Kaminaga Hime to his son was his idea, all along.

And in case you are wondering, no, the Chronicles don’t give any thought about Kaminaga Hime’s position on all of this, which may say more about the 8th century than about the 4th or 5th.

So Homuda Wake gave a banquet in the Hinter Palace—that is, the women’s quarters of the palace, and depending on the source he either gave her the upper seat, or kamiza, or else he set it up so that she would serve wine to Ohosazaki in a special cup. Either way, the conspirators had ensured that Kaminaga Hime would be the center of attention when Homuda Wake launched into an impromptu bit of suggestive poetry—given here in Aston’s translation from the Nihon Shoki:

Come! My son!

On the moor, garlic to gather,

Garlic to gather

On the way, as I went

Pleasing of perfume

Was the orange in flower.

Its branches beneath

Men had all plundered

Its branches above

Birds perching had withered

Of three chestnuts

Mid-most, its branches

Held in their hiding

A blushing maiden

Come! And for thee, my son,

Let her burst into blossom.

Ohosazaki took his meaning immediately and answered with an impromptu poem of his own:

In the pond of Yosami

Where the water collects,

The marsh-rope coils

Were growing, but I knew not of them :

In the river-fork stream,

The water-caltrops shells

Were pricking me, but I knew not of them.

Oh, my heart !

How very ridiculous thou wert !

The Kojiki has a few other songs, though I think you get the picture. The others, by Ohosazaki, talk about her laying by his side and another has a rather, well, questionable line that states that “she slept with me / unresisting”, which, just, ugh. Sigh. Because yes, “resisting” was a thing and consent wasn’t considered necessary, and at some point here we will spend some time on this rather distasteful aspect of court culture, with plenty of appropriate content warnings up front.

But that is all tangential to our main thread, which is the role of Takechi no Sukune and the trust and loyalty he seems to have had at court, which this whole story illustrates very well – and which makes the next story so very strange, when you stop to think about it.

Now it is unsurprising that in all of his work for the state, Takechi no Sukune was not universally appreciated. In fact, it seems that there were those who were rather jealous of his success and his control over the administration of the state. It is a tale as old as time, really—in any political system with limited positions at the top of the heap, there is only room for so many people up at that rarified altitude. And so people were regularly jockeying for position, and even friends could become rivals in their pursuit of status. In Takechi’s case, however, trouble didn’t just come from some random colleague trying to impugne his character. No, the dagger that was thrust towards the Prime Minister came from another direction: His own younger brother, Umashi no Sukune.

It makes a perveted sort of sense, when you think about it. As brothers, they both came with a similar lineage—though we aren’t told if they were full brothers or only half-brothers. But as far as their lineage went, there was likely not much to distinguish one from the other. Even so, it seems that Takechi no Sukune’s own position was, from an early period, based on his personal relationship with the sovereigns and their family, and then it built upon that with all of his works. Meanwhile, we haven’t heard from Umashi no Sukune until now, though his title of Sukune would seem to indicate he’d done something right, though that could have all been due as much to his elder brother’s influence than anything he had personally accomplished.

It is unclear exactly why Umashi no Sukune decided to betray his older sibling—whether he hoped to inherit his powerful station, or whether he just had a grudge from some perceived slight that he had been nursing for some untold period of time.

Whatever the cause, there is no indication that Takechi no Sukune had even the faintest hint that something was amiss. And so, as he embarked on a trip to Tsukushi to inspect that region, he likely had no thought as to the dangerous situation that would soon unfold.

At the court, with his brother gone, Umashi no Sukune seized his opportunity.

He found his way into the good graces of Homuda Wake and, like Wormtongue whispering his dark thoughts to Theoden, he started to slander Takechi to the sovereign. He intimated that Takechi had treasonous plans on the country, and claimed that while he was in Tsukushi he would start to enact plans to break the entire island off from the rest of Yamato. From there he would control all trade and communication with the continent, and that would eventually give him control over the entire archipelago.

One might question if Homuda Wake would truly be swayed by such an outlandish and audacious story. After all, this was Takechi no Sukune, who had served loyally for so many years and had basically helped raise the young sovereign. On the other hand, the accusations were coming from his own younger brother. Furthermore, remember how Homuda Wake had come to power, and the many roles that Takechi no Sukune had played leading up to that. I mean, if anyone knew how to rally and lead an army to put himself or someone else on the throne, it would be Takechi no Sukune

In the end, whether fully convinced or just deciding that he couldn’t take the chance that Umashi no Sukune could be right, Homuda Wake decided he must take action. Fearing the damage that would happen to the realm--not to mention what might happen to him—Homuda Wake had Takechi no Sukune branded as a traitor and sent warriors out to track him down and kill him for his alleged crimes.

Fortunately, Takechi no Sukune’s time as Prime Minister hadn’t just garnered him enemies, but he seems to have had quite a few friends as well. In fact, given how he seems to have operated, I suspect he had made as many, or more, friends than enemies in his long and highly successful career. And so word reached him of the warriors that were hunting him well before they arrived.

Takechi no Sukune was crestfallen by what must have felt like a massive betrayal. After all he had done, had it really come to this? Could Homuda Wake really think so little of him? I can hardly imagine the turmoil he was going through trying to understand how this had happened. But ancient politics were brutal, and having skin in the game wasn’t just a metaphor. For someone in power as long as Takechi no Sukune had been, he must have known that his position at the top made him a target.

While Takechi no Sukune was still reeling from his misfortune, no doubt trying to strategize a way out of this mess, he was approached by a man named Maneko. Apparently this man bore an uncanny resemblance to the prime minister, and he offered to be his stand in—his Kagemusha, if you will. It is unclear whether he made this offer purely out of some sense of civic duty, or if there was some greater obligation that he felt towards the prime minister, but Maneko made his offer freely, knowing full well what it would mean. Nonetheless, he felt it was worth it if it would give Takechi no Sukune time to return to the court and make his case to the sovereign in person.

And so, to throw the assassins off Takechi no Sukune’s scent, Maneko made himself up to look as much like the Prime Minister as possible and then he threw himself onto his own sword.

Local people must have been shocked when they heard the news, and it likely spread quickly through the archipelago. Eventually the news reached the assasins who were still on the road. They were told that Takechi no Sukune had taken his own life rather than let himself be killed. Without a mission left to accomplish, the would-be assassins apparently turned around and headed back home.

And so, making the most of Maneko’s sacrifice, Takechi no Sukune himself—very much not dead—made his way quietly back to the court. One can imagine that he must have done his best to hide his identify, lest word get back to his rivals that he was still alive. We are left to imagine just how he made his way back, but eventually he he snuck back into Yamato.

Once back, he slipped into the palace without being recognize, and once there, he revealed his presence and threw himself at Homuda Wake’s feet. He explained everything, at least as he knew it, refuting any accusations of disloyalty from his brother.

Homuda Wake was in something of a bind. Which brother was really telling the truth? Unsure, and, now presented with two different stories, Homuda Wake interrogated both Takechi and his brother, Umashi. All he had to go on, though, was their individual testimony. There was no evidence that Takechi was plotting anything, other than his own brother’s say-so, but then again, there was no clear evidence to exonerate him, either—and this is well before any concept of “Innocent until proven guilty”. And so, in order to get at the truth, they were both submitted to the ordeal of boiling water.

I am not exactly sure what form this took, but it sounds like they would have had to endure boiling water in some form or fashion, and one imagines that the one who better endured the pain would be the winner. We are told that it took place on the banks of the Shiki river, and Homuda Wake called upon the gods of Heaven and Earth to help decide the case.

Personally I’m imagining that this was something similar to the ordeals imposed in Europe, operating along similar lines. A person would be submitted to boiling hot water, which should severely scald or even burn them. Theoretically some great power—God in Europe, or the kami in Japan—would intervene on behalf of the innocent to ensure that they came out unscathed. Hardly the kind of justice system that I would want to be subject to, but apparently it worked, and Takechi no Sukune was, of course victorious.

As soon as the verdict was read out, Takechi leapt into action. He didn’t even wait for sentencing; he may have been an old man by this time, but he was still spry, and he jumped on his traitorous brother. Gone was any sense of the calm, cool-headed administrator. This was the Takechi who had traveled out to the east and raided the coasts of the continent with Tarashi Hime. He was angry, and he was out for blood.

Apparently such a reaction caught the entire court offguard. They were probably expected him to be nursing his wound from the ordeal. Wrestling on with his startled brother, Takechi quickly pulled his own cross-sword and was about to kill him when Homuda Wake suddenly intervened and parted the two men.

In the end, Umashi no Sukune wasn’t killed, but he was handed over to the lord of Kii. Of course they didn’t exactly have a prison system that we are aware of, so we have to make some assumptions as to what this meant. Perhaps Umashi no Sukune was forced to work as an enslaved servant, or, given his status, he may have simply been held under a kind of house arrest, away from the politics and power of the court. Enforced exile seems to be a common punishment for more high ranking individuals, and perhaps that is what happened here. Either way, we don’t hear any more from him in the Chronicles.

As for Takechi no Sukune, he returned to his work, and despite everything that had passed, he would continue to serve the court until at least the reign of Homuda Wake’s son, Ohosazaki no Mikoto.

He isn’t as prominent, however—in fact, we have only a single reference—a set of poems by the sovereign and Takechi no Sukune referencing the odd occurrence of a wild goose found laying an egg—odd in that geese do not typicallylay their eggs in Japan, preferring their summer nesting grounds up in the arctic tundra, so this would have been an odd occurrence indeed, though why it would be connected to Takechi no Sukune is beyond me, to be honest.

Interestingly there is also a similar entry in the Harima Fudoki that similarly talks about an area named “Kamo”. It was apparently so-named because the wild geese used to gather in that area, and, again, they talk about them laying eggs, which must have been an odd find. In that story, however, the eggs were laid in the reign of Homuda Wake, not that of his son, suggesting that this incident, like so many others, may not be in exactly the right spot.

Regardless, that is the last we hear from Takechi no Sukune, aka Takeuchi no Sukune, at least in the Chronicles. From there we need to look at other sources to see what might have happened to him.

A Kamakura source, claiming to be from the no longer extant Inaba no Fudoki, claims that Takechi no Sukune retired around the ripe old age of 360 years old and headed north, to the country of Inaba. He lived there for a time, and then one day he just disappeared. They found a pair of his shoes at Kamegane hill, or so we are told. Today, you can actually visit the site of Kamegane Hill at Ube Shrine, in the southeast of modern Tottori City, near the Fukuro River. It is just north of the archaeological site thought to be that of the old Inaba provincial office, and the shrine claims the title of the Ichinomiya, or principal shrine, of that ancient country. Here they proudly lay claim to the tradition of Takechi no Sukune, which holds that he was buried in a kofun whose remains can be seen on the shrine grounds.

Other sources—all much later than the Chronicles—suggest he died some time during the reign of Ohosazaki, aka Nintoku Tennou, sometime between the 55th year of that reign—the same year that those goose eggs were found—and the 78th year of the same. These accounts then put him at various ages, all on the upper side of his third century, however. As for the actual place of his death, that’s also scattered across the country, with some traditions having him pass away at Kai, others at Mino, and still others having him remain in the Nara region.

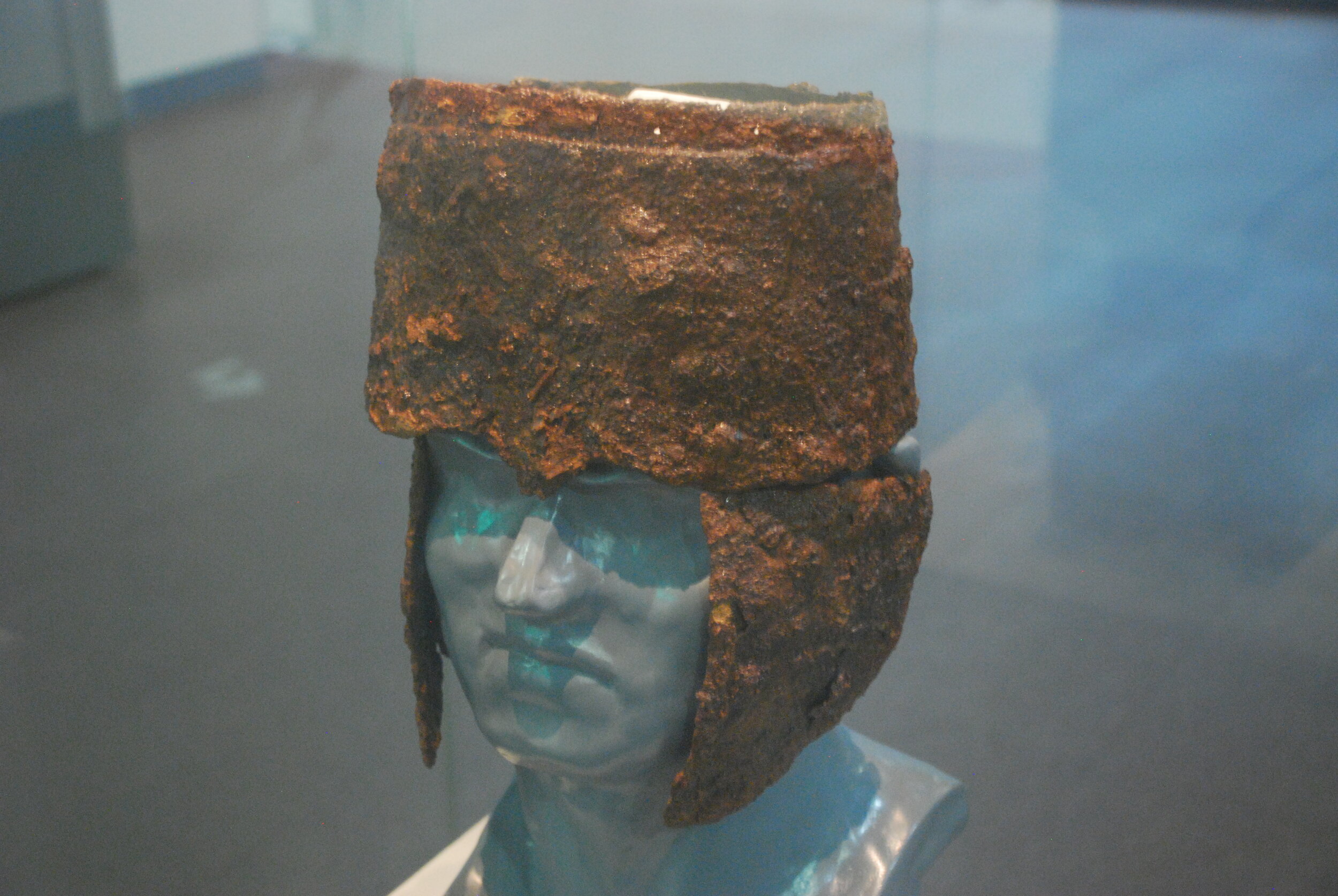

Likewise, his actual kofun is also unclear, though we know he had one. One of his descendants, Tamada no Sukune, is depicted escaping to it in one account of the Nihon Shoki, but they don’t actually tell us where it was. The traditions at Ube Jinja obviously have it up there, but in the Nara basin there is a round keyhole shaped tomb known as Muromiyayama Kofun, formerly known also as Muro no Ohobaka. It sits at the foot of the mountains that form the southern extent of the Nara Basin, in Gose city. Some traditions claim that this is where they laid to rest the famed courtier.

The kofun is the correct age, dating to about the start of the 5th century. It is 238 meters long—about 40 meters shorter than Hashihaka Kofun, thought to be the resting place of Queen Himiko, and less than half the size of the giant Daisen Kofun of Nintoku Tennou. So while it may be similar in scope to previous kingly tombs, it doesn’t really hold a candle to what was going on over in the Furuichi-Mozu area of Kawachi—modern Ohosaka. Still, it is impressive, and if it really was for Takechi no Sukune then it seems like a decent kofun for someone of his status, though its placement in the southern edge of the Nara Basin strikes me as slightly odd—I would imagine a tomb mound closer to the court in the Kawachi area, nearer to the kingly Furuichi-Mozu tombs, but perhaps there was some significance in the Gose region that we don’t have the context for, today.

And that is it for the life of Takechi no Sukune—or at least the life that the Chronicles lay out for us to find. But we are still left with quite a few mysteries. Perhaps the largest amongst them is what, in all of this, is actually true?

Well, most of this is going to be conjectural, but I’ll provide some of my own theories. First off, I think that it’s important to note that Takechi no Sukune features in the lineages of some rather important families in the 7th and 8th centuries. Not only is he linked as an ancestor of the royal lineage, but he is also said to be one of the ancestors of the Soga family. The Soga were extremely powerful in the 7th century, to the point that they were effectively running the government, with power that rivaled that of the royal house, itself. There were also numerous other families that traced their lineages back to Takechi no Sukune through one means or another.

So it would make some sense that the ancestor of these powerful families would be an important figure that couldn’t just be written out of the story.

On the other hand, it is possible that we have the opposite effect, here—rather than Takechi no Sukune being important because those families claimed him as an ancestor, it could just as easily be that those families claimed him as an ancestor because he was important. I mean, everyone tried to claim some connection to the royal family, if they could, and Takechi no Sukune is said to have descended from one of the likely fictional sovereigns before Mimaki Iribiko. So there’s that. But also, if he was a known character in so many of the oral histories, it may be that he was a great legendary figure to help bolster your own family’s position in the status-conscious court of the 8th century.

And there is some evidence to suggest that this is the case. You see, many of the more famous families claiming him as an ancestor appear to be doing that through another legendary figure of this time—someone I had actually planned to talk about this episode but, well, we’re already getting a bit long so I think we’ll cover him next time. His name is Katsuragi no So tsu Hiko.

And what stands out, here, is that title: “Hiko”. Now we’ve seen many examples of “Hiko” already. Today it is often translated as Prince or Lord, and we often talk about the Hiko-Hime ruling pairs that are a staple of the earliest stories, where “hiko” appears to be an old word for some kind of territorial ruler or authority.

The key there is that it is an older title. Sukune, and even Wake, appear to be later signifiers of authority, and, in fact, we have one piece of evidence that appears to help place all three of these titles in context for us.

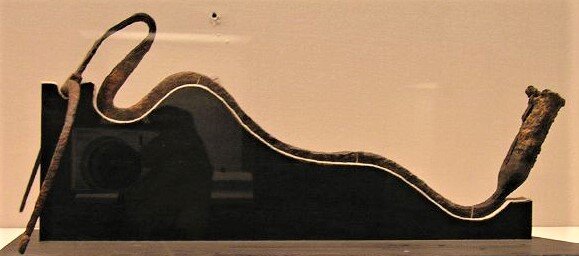

You see, we have a sword dated to the late 5th or early 6th century—probably about a century out from our current temporal coordinates within the narrative. It had been buried at Inariyama Kofun, and it is important because it contains a lineage inscribed on the blade that takes us up to the time of the sovereign Wake Takeru, aka Yuuryaku Tennou. This lineage, starts with Oho-hiko, who may have been the same one mentioned as one of the four generals of Mimaki Iribiko, and it progresses through several generations. In the earliest generations we see a transition in the titles from Hiko, to Sukune, to Wake. If we assume that the family continued to grow more powerful, with successive generations ascending to new heights, then we would expect to see the same kind of progression and escalation of titles in other lineages as well.

For the offspring of Takechi no Sukune, the vast majority of them are also given the title of Sukune, presumab ly inherited from their father. One notable exception to this pattern is So tsu Hiko—if he was truly Takechi no Sukune’s son, then we would expect that he would also have a title like Sukune, or possibly even Wake.

In all likelihood this stems from the fact that So tsu Hiko wasn’t Takechi no Sukune’s son at all.

But, if that is the case, it just leaves us with more questions. If there was no direct connection to these families other than one they made up, then why, again, was he mentioned so many times and in so many places?

Personally, I can’t help but wonder if he was more than what he is made out to be in the text—and that is quite a lot. Perhaps “Prime Minister”, or “Oho-omi”, was a convenient way to explain all the things the stories said he had done. He may have even been something of a legendary figure, but they couldn’t quite slot him into the royal lineage in the way they did with everyone else.

I also wonder if he wasn’t, in fact, a co-ruler. If the theory of co-rulership is true—and it wasn’t actually gendered—then perhaps he wasn’t just an administrator, but was actually a co-sovereign. To that point, I can’t help but notice the similarities between his title, Oho-omi, the Great Minister, and the 5th century title used for the sovereign, “Oho-kimi”.

There is also the business of him and Okinaga Tarashi Hime, where the two often look like they are working extremely closely together, and while that could be explained as the natural response to their situation, I can’t help but wonder if it is more than that.

Another possibility is that he wasn’t a co-ruler, but that he was the chief of one of the other countries in the archipelago—perhaps even a king in his own right. Remember, we are still seeing evidence of some independence in places like Kibi, Izumo, and Tsukushi, even if they may have largely been working with the Yamato hegemon.

If that were the case, it seems the most logical place for him to have been was probably somewhere in Kyushu, which many of the stories connect him to. Perhaps the story of him possibly breaking away and declaring himself the sovereign was not just a fanciful conspiracy theory, but an actual threat to Yamato’s dominance. After all, we’d already seen rulers at the Shimonoseki Straits reportedly telling people that they were the actual rulers of the archipelago. Some have even suggested that most of the actions of the Wa on the peninsula were actually referencing some powerful, northern Kyushu entity, rather than Yamato as we think of them.

There is a less exciting possibility. That one suggests that these stories aren’t actually of the same person, but that Takechi, or perhaps Takeuchi, was actually more like a title that got passed down over time, and that multiple different people held this position during different reigns.

Of course, none of that is really provable without corroborating evidence, and given the lack of any written history prior to the early 5th century, it seems unlikely that we’ll get much more than speculation, at least for now. Heck, there are even those who don’t believe that any of this is even remotely historical, so there’s that, too.

Before we close, though, I do want to touch on one more thing. It is impressive that Takechi no Sukune is so prominent across so many stories, but the Chronicles don’t seem particularly interested in how long-lived he had to have been. Which may give us some evidence, however sketchy, to take another look at just how long people were reigning.

For example, let’s make the assumption that Takechi no Sukune was, indeed, extremely old at the time of his death. While it would probably be odd, let’s assume that he lived for roughly 80 years, and that he died during the reign of Homuda Wake—the incident with Ohosazaki could have just as easily happened when the sovereign was still a young prince. If we assume he passed away in the first or second decade of the 5th century, then he would have come into the world some time towards the start of the 4th, perhaps even as early as the 320s or 330s, with him only being in power from the latter half of that century, since he wasn’t running a country just after he was born. So looking at his professional career, starting with the Oho Tarashi Hiko and continuing to Homuda Wake, we have all four sovereigns of the Tarashi dynasty and then Homuda Wake—five reigns in total. Even allowing that he likely wasn’t in power until late in Oho Tarashi Hiko’s reign, that gives us reigns averaging about 15 years a piece. That’s much shorter than anything claimed in the Chronicles, of course, but much more realistic. Average reign lengths in the latter part of the chronicles, not including Homuda Wake and his immediate successor, average about 11 to 12 years, which makes sense if you assume that typically a reign starts after the death of the previous sovereign—most monarches are coming to the throne when they are much older.

That doesn’t entirely solve our issue of dates, but I do think that it is a useful tool to try to see how, rather than Takechi no Sukune’s lifespan being incredibly long, it is more likely that the reigns that we’ve been seeing up until now were much shorter.

And so, there you have it. The life and times of Takechi no Sukune. I really do think that he is one of the interesting figures in this period, perhaps in part because I suspect he was largely ignored as the Chroniclers were messing with everything. Sure, his timeline gets dragged out with everything else, but I can’t help but wonder if he wasn’t actually a real person, and probably there for the actual coalescing of the early hegemony. The story suggests that when he started his career, Yamato was still largely just a powerful central state, with no real hegemony much beyond the Nara Basin, and that by the end of it Yamato was making alliances and working as a mover and shaker on the Korean continent. The latter half of the 4th century in particular had seen tremendous growth, and if Takechi no Sukune were there for it, well, I think that would be pretty exciting.

Next we’ll talk about someone whose feet are more firmly planted in history—he even gets some love from the continental sources. He is Katsuragi no So tsu Hiko, and though his exploits may not quite rival those of Takechi no Sukune, he was party to some rather important events, especially dealing with Silla and the continental powers.

So, until next time, thank you for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate through our KoFi site, kofi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the link over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode. Questions or comments? Feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page.

That’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Shichirō, M., & Miller, R. (1979). The Inariyama Tumulus Sword Inscription. Journal of Japanese Studies, 5(2), 405-438. doi:10.2307/132104

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1

![Takechi no [Sukune] no Ōmi on a Japanese 1 yen note from 1916.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d1a2aa7e7ccfd0001a4f03d/1627739155754-OJSEOWQ7CJ3BU0PC2KHP/Revised_1_Yen_Bank_of_Japan_Silver_convertible_-_front.jpg)