Previous Episodes

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

When Homuda Wake died, we are told that he left his youngest son, Uji no Waki Iratsuko, as Crown Prince. However, there were still two other brothers with a claim to the throne, and not everyone was committed to upholding their father’s wishes. This episode we discuss the succession crisis that arose after Homuda Wake’s death. We also try to provide a little external context, looking beyond the story in the Chronicles. Finally, we briefly touch on a UNESCO World Heritage Site associated with this whole episode.

The Dual Kingship Model

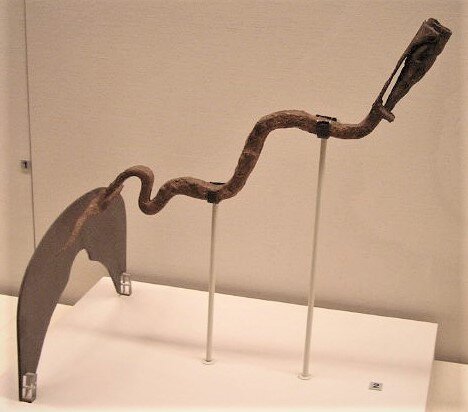

One of the discussion points in this episode is the dual kingship model, as presented by Kishimoto Naofuji in his article, “Dual Kingship in the Kofun Period as Seen from the Keyhole Tombs.” He builds on the previous theory of gendered co-rulers—the Hiko-Hime-sei—suggesting that the co-regents weren’t necessarily gendered, but simply had different functions. He explains this through the grave goods and the shapes of the various tombs: While they all have the same general “round-keyhole” or “前方後円” shape, there are slight differences in the tiers and shape, such as various protrusions, that seem to come from different “lineages” of tomb construction. Since these tombs are roughly equal in size and therefore assumed to be roughly equal in status, and the two lines continue through successive tombs, he suggests that they were for royal elites with slightly different functions.

Of course, it is hard to see any such model in the continental references. Nowhere do they explicitly reference multiple “kings”, though in the Wei Chronicles they do mention someone who helped with the administration while Himiko handled more sacred and mystical duties. One reason for this lack in the external sources may be that the continental chronicles just didn’t have a full understanding of Wa politics and therefore assumed that they governed under rules similar to the ones they themselves knew.

It is also possible that this whole thing is wrong. Without access to most of the kingly kofun, we may never know for certain who is buried there—and even with access there is likely to be debate. But it does keep us on our toes and should be a good reminder not to trust everything that the Chroniclers throw at us.

Prince Ō Yamamori (大山守皇子) and Prince Nukata Ō Naka tsu Hiko (額田大中彦皇子)

The connection between the prince known as Ō Yamamori and Prince Nukata no Ō Naka tsu Hiko is still somewhat uncertain. It seems clear that they were conflated into a single character by the 8th century chroniclers, but it is quite possible that in truth, their stories were combined at a later date. This seems further emphasized by the fact that in the story about Ō no Sukune and the rice-lands of Yamato, the Prince in question is referenced consistently as Nukata (or Nukada) no Ō Naka tsu Hiko. However, in the scene after this, it is Prince Ō Yamamori who is referenced. The placement and the grudge would seem to indicate that the story of the rice-lands incident added to the frustration that Prince Ō Yamamori felt with his position, and there is even a mention that the reason Prince Ō Naka tsu Hiko felt entitled to the lands was because they belonged to the “Yamamori”.

However, I would be remiss not to note that there is a later story—some 60+ years later—that also mentions Prince Nukata no Ō Naka tsu Hiko. This is many decades after Prince Ō Yamamori’s death. Unfortunately, that simply leaves me with more questions.

Regardless, we maintain here Aston’s assertion that the two were actually one and the same, with Ō Yamamori being the title (Great Mountain Protector) and Nukata no Ō Naka tsu Hiko may have been the prince’s actual name, such as it is.

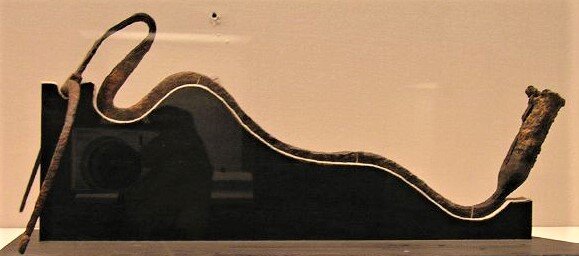

Ujigami Shrine (宇治上神社)

This shrine is well late of our narrative, as we don’t have evidence for it until some time between the 8th and 10th centuries, but it still is interesting and it is connected to our story because it enshrines three of the individuals we discuss: Homuda Wake, aka Ōjin Tennō, and two of his sons: Uji no Waki Iratsuko and Ōsazaki no Mikoto. On top of that it is an UNESCO World Heritage Site, and if you are ever in Uji city, you should check it out.

The honden, or main worship hall, of Ujigami Shrine—one of the oldest extant examples of shrine architecture, in this case dating back to the Heian period. This hall is a national treasure and a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

-

Welcome to Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan. My name is Joshua and this is episode 49: Three brothers, one throne.

Quick content warning upfront in this one—there is some brief mention of suicide in this episode, as well as other forms of violence in this episode. We’ll add notes about it to the episode description when it is released if you need more specific details.

Also, before we get going a quick shout out to Craig and Shinanoki for donating to support what we do here. Also thanks to Shinanoki to making the suggestion to open “memberships” on Ko-Fi, which is a new feature, so now you can either drop us a one time payment or set up a monthly donation. That is all over at Ko-fi.com, that’s “K”-“O”-“DASH”-“F”-“I”, “dotcom”, “Slash” “sengokudaimyo”.

More on that at the end of this episode.So, when we left off at the end of our last episode, Homuda Wake was dead. The sovereign who had ruled over Yamato through so many eventful years was no more. Over the course of his reign, Yamato’s influence on the peninsula had expanded, along with its influence on the rest of the archipelago. Weavers, seamstresses, smiths, and more had made their way from the continent to the islands where the Wa lived, spurring advancements in a wide swath of different fields. The islands now had horses, and people could read and write. And one thing that seems true around the world: reading and writing greatly increase the speed at which a people can import new ideas, thoughts, and philosophy.

One thing was for certain: things were changing, and fast. Like the parable of the frog in a pot of water, we don’t always notice change until well after it has happened. In fact, we often tend to see change as though it wasn’t change at all—we project back on the past an image consistent with what we know. Maybe we make some comparative notes between how it was when we were growing up and how it is today, but there is a tendency to assume that anything quote-unquote “beyond living memory” was just some version of life like our grandparents told us about.

How that’s relative here is that we are watching change happen over some two hundred years—from the end of the Yayoi period in the 3rd century and the mention of Queen Himiko to the current era in our story. For comparison, as of this episode, recorded in September 2021, the US constitution is roughly 233 years old – and the Edo period in Japanese history lasted for a little over two and a half centuries, depending on how you count it. And both those periods have been marked by enormous change as well.

During the 200-year span in our narrative, we have seen the emergence of small countries, or perhaps proto-states, across the islands. It may not be fully correct to assume that they had complete control, even within the borders attributed to them, however. The polities that arose from the Yayoi period were based on a practice of wet-rice cultivation and trade that saw them spread out the plains and river deltas, as well as along the coastal regions, but at the same time various other lifeways continued in the mountains, which even then made up the majority of the archipelago’s landmass. Given that most fertile plains in Japan are around the deltas where rivers empty into the sea or large lakes, like Lake Biwa, it seems quite understandable that the waterways would also be an important means of travel and communication, which only further draws a distinction between the plains and the mountains.

Which isn’t to say there weren’t population centers built around other commodities, such as the jade-producing regions in the Koshi region, but these appear to have been exceptions, rather than the rule. Even the various mountain communities interacted with the rice-growing cultures on a regular basis, though they are clearly depicted as being outsiders.

Of all of these early states, Yamato appears to have been the largest and most powerful of these entities, but all the same it is questionable how much direct control it had beyond its own borders. Control, however, is different from power. Levers of power are complex, even today. There are many types of power that any individual or group can access and deploy to their benefit. Legal and military power are the ones we probably think of most often when we think of a modern state or country, but influence can be achieved through other means as well. Religions often wield considerable power through the influence they have on their followers, such that leaders like the Catholic Pope or the Dalai Lama might be seen as highly influential figures on the world stage, despite not having the typical trappings of a state apparatus. Economic and trade networks also create their own levers of power that can influence others. Or you might just be able to use logic and persuasion to get people on your side and to do what you want them to do. And then there is simply the force of tradition, and traditional relationships, which may generate influence between groups. There are so many ways that one can influence others, it isn’t just about being the person at the top of the legal pyramid. After all, what is a leader if nobody decides to follow them?

And whatever else we may say about the state of Yamato, it does appear to have become a leader in the archipelago. This had likely been accumulating through a variety of means, one of them possibly being the spread of the cult of Mt. Miwa and a burial ritual for elites based around monumental tomb structures – the giant kofun that we’ve been talking about, which by this time period were reaching truly impressive sizes. Whether this cultural practice was part and parcel of the spread of direct Yamato power, or a separate influence, I can’t really say, though they may have encouraged one another. Either way, as this ritual and the knowledge of its specifics was based in the area of Yamato, that seems to have given the Yamato elites a leg up in their dealings across the archipelago. These relationships, properly cultivated, and reinforced through marriage politics across the various countries, had grown into something more—perhaps a kind of confederation.

A similar process seems to have been going on over on the peninsula, within the areas of the Samhan, the three Han of Ma, Jin, and Byeon. Here, we know a little from the accounts in the Records of the Three Kingdoms, including the Wei Chronicles, as well as the stories from the annals of the Silla and Baekje kingdoms that eventually were recorded in works like the Samguk Sagi and the Samguk Yusa. In particular, in the Baekje Annals we are told that there was a single ruler, or King, of the Mahan confederation, but that position was replaced by Baekje as they began to conquer, assimilate, and subjugate their neighbors. Silla, we are told, grew up out of an alliance of six members of the Jinhan, eventually rising to power as the pre-eminent state in that region. Byeonhan looks to have been in a similar process, with various mentions of a King of the states known as Kara, or Kaya, as well as a ruler of Nimna—whether or not those were the same individual is hard to say, but the Chronicles seem to suggest that there were different positions. Kara, however, seems to have been late to the game—perhaps it never had the external impetus of others to bring the various communities together, or perhaps, trapped as it was between Silla, Baekje, and the Wa of the archipelago, it was pulled in too many directions, given that it was the crossroads across which the others would often march in their conflicts. This is a position the entire peninsula would find itself in, later, but for now it appears to have affected the growing states of Kara the most.

So, looking at the details of how these states on the peninsula consolidated their power, it is reasonable to assume that a similar process was at work in the archipelago – although the Chronicles, being the official record of the Yamato court written centuries after the fact, don’t go into the same level of detail of how their own sausage was made. This power consolidation wasn’t necessarily a conscious decision on any one person’s part. There was no great unifier to point to who was bringing these states together—no Oda Nobunaga with his armies, nor a Julius Caesar or Alexander the Great. At least, not yet. And still, a shared culture was being built through various rituals and ties across the various countries of the islands.

Early on, we see this not only in the monumental tombs, but in the distribution of elite goods. Bronze mirrors seem to have been the most popular such item, at least early on. These were likely acquired from the continent, from groups like the Wei and the early Jin courts, and then distributed by a central authority, whom many assume to be the Yamato court. In addition to those acquired from the continent, local copies were also produced. The importance of these mirrors is further emphasized in the stories, such as when various local lords bring out their finery to meet envoys of Yamato, or even in the depictions of how Yamato’s own missions were decked out. Furthermore, the mirror’s place in the legend of Amaterasu also seems to be key.

But as the centuries went on, the 4th century, into the 5th, saw another item, also mentioned in the story of Amaterasu, which we start to see more of, even as incidents of bronze mirrors begin to decline. These are iron swords, and as we start to see more of them in tombs, especially as the bronze mirrors diminish, we can make some assumptions as to where the people of the archipelago were placing their values. Mirrors may represent ritual authority, but they also represent a kind of wealth. Mirrors have a use, but having many mirrors seems to be more about strict wealth—and access to the kinds of continental goods that would make someone important in the early periods. Swords, along with armor and other tools of war, are also signs of wealth, as iron was still largely obtained through continental trade, but these have a much more direct use, as well. After all, arm 100 people with mirrors and, unless you are constructing an Archimedean death ray, they aren’t going to do a whole lot in a fight. Arm those same 100 people with swords and armor, and you have a formidable fighting force, especially when previous forms of arms and armor consisted largely of bronze or stone and lacquered wood. It seems that there was, in this period, a greater emphasis on military might and achievements.

Which isn’t to say that it was all peace and love before—we certainly have examples of the kind of mass violence seen in inter-group conflict early on, but this doesn’t appear as one of the defining aspects of the social elite as it would come to be later on. This change may be understandable given the turmoil that had taken place on the continent. Goguryeo had destroyed the old commanderies, which no doubt caused disruption in the trade networks. That could help explain increased incidents of Wa raiders along the coast of the peninsula—though for all we know this may have been something that had been going on for much longer, with nobody around to record it. It is also possible that the concept of a warrior elite was coming over from the peninsula with waves of immigrants, many of whom were captives or refugees; victims of the violence that seems to have characterized this period.

Evidence of immigrants can be found across the archipelago. For one thing, immigrants are tied to many places in the archipelago, and specifically to the current dynasty. We’ve talked a little bit about immigrant influences in places like the country of Toyo, as well as Kawachi, Izumo, and Koshi on the main island of Honshu. Indeed, Kawachi, in the south of modern Ohosaka, is a hotspot in the chronicles for immigrant presence, and it seems to have been a the center of activity, as that is where this dynasty‘s tombs, and many of their supposed palaces, were located. The narrative of the royal family even claims ties back to Silla princes and there is evidence that they may have also had marriage ties to the Baekje royal line.

We’ve also heard about artisans brought over from the peninsula to revolutionize weaving and other crafts. In the 5th century we will see the rise of sue-ware pottery, a kind of high temperature fired stoneware that likely came over from Kara. You see the same techniques adopted in Silla for their pottery around the same time. These techniques required extremely high temperatures, requiring a new kind of kiln, built upon a hillside. These same high-temperature techniques would have been useful in the process of extracting iron, necessary for all of the arms and armor we are seeing.

But of course, when it comes to pottery, it isn’t just peninsular style stoneware that we see—local traditions were also evolving. In particular, we see more and varied styles of haniwa, those terracotta clay figures that adorned so many of the kofun, particularly the monumental kingly kofun. Eventually these figurines would come to be important windows in to what life actually looked like at this time.

And as we are talking about the march of time and things that were eventually forgotten, I’m also reminded of Professor Kishimoto Naofumi’s dual kingship model. We talked about this a little bit previously, but this model states that for a time, there were actually two sovereigns: one who ruled as a sacred authority, interpreting the signs of the kami and directing the spiritual well-being of the land, while another dealt with more secular matters, having to do with things like administration of the government as well as any military activities. This goes back to the description in the Wei Chronicles of how Queen Himiko ruled through her spiritual power, and others seemed to be handling the day to day work of administering Yamato, and it is further indicated in the shapes of the kofun themselves. In fact, Prof. Kishimoto points to aspects of their shapes like certain protrusions, and the number of tiers, that appear to show at least two parallel lineages for tomb construction. I wanted to bring this back up, because otherwise we get just the view of the Chronicles, which crams all of the rulers into a single, largely unbroken, patrilineal descent model, either because the 8th century chroniclers couldn’t conceive of anything different from their current model or possibly because they had drunk too much of the continental KoolAid in regards to what was a quote-unquote “proper” model of kingship.

So here we have the possibility for two separate lines stretching back to at least Himiko. When, with Homuda Wake, the power of Yamato moved from the Nara basin out to Kawachi, with its greater access to the sea, that could be a demonstration of another chiefly line taking control, or it could be indicative of a desire for easier access to the waterways that led to the peninsula and the rest of the continent. Either way it pulls the sacral ruler further west, away from the holy mountain of Mt. Miwa, and seems to turn the face of Yamato towards the trade connecting it with the continent.

And that brings us back to where we are in the narrative. The sovereign, Homuda Wake, was dead. His body may have been laid out for a time—mogari—before being entombed in one of the kingly kofun. Tradition says that this was Kondayama Kofun, and based on the size it was likely constructed well before his death, as some have estimated that construction of something that large would have taken at least a decade. Tomb construction was probably a business all unto itself, constantly in motion, organizing the labor, resources, etc. for both the tombs of the rulers but also other elites across the archipelago. The construction would likely have been taking place as the backdrop to Homuda Wake’s court.

Now from what we are told, the succession issue after Homuda Wake passed should have been pretty cut and dried. After all, Homuda Wake had set up his son, Uji no Waki Iratsuko, as the Crown Prince. As for his other two eligible sons, he had actually set them up as well. Oho Yamamori had been put in charge of the mountain areas, while Oho Sazaki, whom you may recall from last episode gave Homuda Wake the answer he had been looking for in terms of his succession decision, was made the Assistant to the Crown Prince and put in charge of administration—which sounds vaguely similar to idea that he may have been set up as a co-ruler, per professor Kishimoto’s model, while his brother, Uji no Waki Iratsuko, was set up to succeed Homuda Wake directly.

Whatever was actually going on, of course the story in the Chronicle maintains the story of a single throne and a single ruler, and Uji no Waki Iratsuko was supposed to be that ruler. But, as you might have guessed, that isn’t how everyone saw things. Now Oho Sazaki had no problem with this arrangement, we are told. He immediately turned over the reigns of government to his brother. Uji no Waki Iratsuko, on the other hand, well he didn’t actually want to take the reigns of power himself. He looked at his older brother, and everything he was doing to run the country, and he tried to turn everything over to him. Oho Sazaki wouldn’t hear of it, of course—their father had made his decision, and Oho Sazaki was determined that they would stick to it.

Meanwhile, their eldest brother, Oho Yamamori, aka Nukada no Oho Naka tsu Hiko, had other ideas. He wasn’t at all pleased with how things had turned out, and he was more than willing to take matters into his own hands.

The first we hear about Oho Yamamori gathering power is in the Nihon Shoki, and it is something of an ancient legal dispute. You see, he attempted to use his position to take administration of the official rice-lands and granaries in Yamato from a member of the court, Ou no Sukune, claiming that the lands had originally been a part of the Mountain Warden, or Yamamori, land. As Oho Yamamori, he believed that he should have governance over those lands and how the granaries were run. From a western perspective, this is like requesting the keys to the royal vault. From at least the 8th century, when the Chronicles were written, and probably going back to the early structures of wealth in the rice-growing Yayoi culture, control of the production and distribution of rice was one of the main features of elite administration. Owning rice-land, which is to say being entitled to the taxes on that land, as well as handling the granaries where taxed rice was stored would provide a tremendous income boost, as throughout most of Japan’s history, it was common for the one controlling the taxes to take some amount for themselves, as long as the state got what it was owed.

And so it is little wonder that Ou no Sukune was taken aback at having these fields and granaries removed from his administration. He went Homuda Wake’s designated heir, Uji no Waki Iratsuko, to submit a report and ask for a ruling, but Uji no Waki Iratsuko delegated—perhaps showing that he was cut out for leadership after all. He sent Ou no Sukune to his older brother, Oho Sazaki no Mikoto, to make the report to him, instead. Of course, Oho Sazaki had been administering the government for his father already, so he knew what needed to be done. In this case he went to a man named Maro, the ancestor of the Yamato no Atahe. He asked Maro if it was truly the case that that the granaries and rice-land originally belonged to the administration of the Yamamori. This was probably because much of the early Wa legal system seems to have been based on precedent and tradition. It is, of course, unclear how such precedent would be passed down originally—perhaps there were specialists among groups like the Katari-be who memorized not only genealogies but important events as well. After the advent of writing, court families would maintain their own diaries and records of what had happened, and why, and these would be passed down, creating private repositories of precedent that helped cement their family’s status and importance to the court.

In this case, however, Maro was at a loss, but he suggested that they contact his younger brother, Agoko, whom he was sure would have an answer for them. Unfortunately, Agoko was off on a mission in Kara, and so Ou no Sukune was sent to recall him. Ou was given command of some 80 fishermen—one might say a boatload of fishermen—from Awaji to act as oarsmen. There seems to be a correlation that the more oarsmen, the faster a boat will travel, and so this seems to indicate he was sent off with all haste.

Ou no Sukune made it to Kara and found Agoko and brought him back to the court. Agoko, who must have been quite the student of the old stories, told the court what he knew. According to Dr. John Bentley’s translation in the Sendai Kuji Hongi, aka the Kujiki, Agoko said: “Tradition says that during the reign of the Great King who ruled from the Makimuku Tamaki Palace—which is to say Ikume Iribiko, aka Keikou Tennou, the 11th sovereign and part of the previous dynasty—the authority was given to Heir to the Throne, Oho Tarashi Hiko, who established the granaries of Yamato. At that time, the edict read, ’All granaries of Yamato are to be the granaries of the Great King and not the property of the child of a Great King. If the Great King is not in power, then the granaries are not his.’ Therefore this land is not the land of the Yamamori.”

While that is likely an insertion by the Chroniclers—after all, we have no evidence of written edicts from the time of Oho Tarashi Hiko, for one thing—the answer that Agoko was giving was pretty clear: The granaries and rice land all were owned by the actual sovereign—the Oho Kimi, or Great King—so Prince Oho Naka tsu Hiko – aka Oho Yamamori - could get bent. Sure, Uji no Waki Iratsuko and Oho Sazaki were still vacillating on who should actually be running things, but it wasn’t Oho Yamamori , so he couldn’t just go around demanding control of the rice lands and granaries.

Oho Yamamori was at a loss. He apparently didn’t have anyone on his side to refute Agoko’s argument, and so he dropped his case. Specifically we are told that he “realized that he was in the wrong”, and because of his contrition his brother, Oho Sazaki, forgave him and didn’t do anything to further punish him for his actions.

The story goes on that Oho Yamamori was fuming. First, he had been passed over to inherit the throne by his father, Homuda Wake, and now he had been rice-blocked by his two younger brothers. *He* was the eldest and *he* was entitled to sit on that throne, and he would do whatever it took to make sure that came true. And so he started to raise an army in secret to kill his brother, Uji no Waki Iratsuko, the heir to the throne.

“Secret”, however, is a relative term. Word of Oho Yamamori’s plans reached their middle brother, Oho Sazaki no Mikoto, who immediately went and told Uji no Waki Iratsuko, who in turn raised up an army of his own. The Kojiki tells us that these men were concealed along the banks of what may have been the Kizu River, south of Uji, and that curtains were placed at the top of a nearby mountain or hill, to make it look like Waki Iratsuko was there, holding court. They even dressed a decoy up and placed him on a dais so that it would further seem like it was Waki no Irtasuko up there. The Nihon Shoki and the Kujiki suggest that this was the location of Waki Iratsuko’s own palace—hence the “Uji” in his name. Either way, Oho Yamamori approached with his men, expecting to catch him unawares.

Meanwhile, Waki Iratsuko had put on a disguise. This is one feature that all of the Chronicles agree on—he disguised himself as a common ferryman and set himself up on the side of the river. Some accounts even claim that he greased the boats to make them more slippery. And it wasn’t only Waki Iratsuko who had disguised himself—Oho Yamamori had concealed his troops and moved them in secret, while he, himself, wore clothing over his own armor, to hide his martial intentions. When he finally arrived at the river, he looked across and saw what he thought was Waki Iratsuko on the other side. Confident that his victory was a mere boat ride away, Oho Yamamori got into the ferry, not realizing that the commoner running it was none other than his own brother.

Glowing the confidence of a comic book supervillain just before his plans come to fruition, Oho Yamamori posed a cryptic question to the ferryman, asking him if he thought that he could take the “huge enraged boar” on the mountain on the other side. At this the Waki Iratsuko said that he would not take the boar, and then suddenly he tipped the boat, dumping his brother, Oho Yamamori, into the river.

As Oho Yamamori floundered in the river, fighting against the weight of his armor, he begged the ferryman to help him, still not realizing it was his brother. Of course, he was a royal prince, so this wasn’t just some exclamation, but it was sung out in lines of poetry. Or so we are told—that may just have been a narrative device to help remember and recount the dramatic part of the story. Either way, he called out, and, when no help was forthcoming, he tried to swim to shore. As soon as Waki Iratusko had tipped the boat, however, his own men arose on the banks of the river, bows in hand, and they kept Oho Yamamori from reaching either bank before he finally sank beneath the water. Later they would search the river near where he went under and eventually they found him as their poles hit his metal armor, and they dragged his body out of the river at a place known as Kawara, said to be part of modern Kyoutanabe city, just south of Uji. There is a poem of grief attributed to Waki Iratsuko, who *had* just thrown his own brother overboard and watched him drown, after all. Later, he would have Oho Yamamori buried in a tomb on Mt. Nara—traditionally identified as Sakaimedani Kofun, aka Narayama-baka, north of modern Nara city, south of the supposed site of the conflict. Oho Yamamori’s line didn’t end with him, however, and several families traced their lineage back to this figure.

So with that out of the way, one might assume that Uji no Waki Iratsuko had finally come into his own. He had shown that he could raise an army, outsmart a foe, and take the necessary steps to stay in power—even if it meant the death of his own older brother. One assumes he could have used his victory to cement his place in the lineage. And yet… he *still* insisted on making his older brother, Oho Sazaki no Mikoto, take the throne. And Oho Sazaki continued to defer, claiming he didn’t want to go against his father’s wishes. And so for a while there they were, each in their own private homes, which should have become the new court once Homuda Wake passed away, but each refusing to take up the mantle. Waki Iratsuko had his palace up in Uji and Oho Sazaki was probably living in Naniwa—modern Ohosaka.

Things were so bad, that people weren’t sure what to do. For example, one day a fisherman, or “ama” in Japanese, came to the Uji Palace with a mat filled with fresh fish to offer up to the sovereign. He approached Uji no Waki Iratsuko with the gift, since he had been named as Crown Prince and successor by the previous sovereign, Homuda Wake. But Waki Iratsuko refused the gift. “I am not the sovereign,” he told the fisherman, and anyone listening. He insisted that the gift should be presented down river at the Naniwa palace of his brother, Oho Sazaki no Mikoto. This was a journey of probably around 40 km, or 24 miles, and would have taken a day on foot—perhaps not quite so much on the river, but still something of a hike.

And so the fisherman dutifully took his catch down to Naniwa, where he presented it to Ohosazaki no Mikoto, but Oho Sazaki also refused it, just as had his younger brother. He would not go against their father’s orders, and so he commanded the fisherman to head back to Uji no Waki Iratsuko.

Now by this time the day had grown late, and the fish were starting to go bad with all of the travel, and so the fisherman tossed the whole thing and resolved to try again the next day with a new catch.

Sure enough, he caught the fish and wrapped them up, just as before. He went to the palace in Uji, this time prepared to explain that Oho Sazaki had sent him back, but it was no use. Just as before, Uji no Waki Iratsuko insisted that he was not the sovereign and that any offerings had to be made down in Naniwa to Oho Sazaki. Once again the fisherman made the treck, but just as had happened the day before, Oho Sazaki refused, claiming he was not the sovereign. Once again, with all the back and forth, the fish were rotten and no longer good for anyone to eat, and we are told that the fisherman just threw up his hands and wept, for there was nothing else he could do.

From this came a saying: “Ama Nare Ya, Onogamono kara nenaku”—“There is a Fisherman who Weeps on account of his Own Things”.

And it seems like things may have continued on like this, which couldn’t have been good for anybody. Somebody was going to have to budge, but who would it be.

According to the Nihon Shoki, it was Uji no Waki Iratsuko who finally took matters into his own hands. Seeing that his older brother would not give in, and realizing that this couldn’t continue like this or everything would fall apart, Uji no Waki Iratsuko, we are told, took his own life.

As soon as the shocking news reached Waki Iratsuko’s brother, Oho Sazaki, he raced upriver to Uji. As he got there, they were already preparing Waki Iratsuko’s body for burial, and we are told that he was lying in the coffin, dead, when Oho Sazaki arrived, weeping and wailing and pouring out his heart. It seems, however, that Waki Iratsuko was not quite ready to fully leave the mortal plane, however. Though he seemed to be dead as a doornail he suddenly sat bolt upright in his coffin and addressed Oho Sazaki. The zombie prince told his older brother not to grieve, because this was in the best interest of the country, and Waki Iratsuko then asked Oho Sazaki to take Waki Iratsuko’s sister—a daughter of Homuda Wake, but by a different mother than Oho Sazaki—as a wife and to install her in one of the side palaces. After saying all of that, he then fell down dead once more. Tradition states he was buried at Maruyama Kofun in Uji—also just known as Uji-baka—a round keyhole style tomb on the north side of the Uji River in modern Uji city.

And so it was that Oho Sazaki no Mikoto, also known as Nintoku Tennou, finally ascended the throne.

We’ll talk about his reign over the next few episodes, but let’s quickly take a look back at this story. One of the things that struck me as I was reading this in the different sources is that this seems to be one of the stories where there is generally agreement between the various chronicles. It isn’t something that just shows up in one or two, but all three, and the with similar beats in the action, with only small differences in the details. So either they were drawing from the same story or it was a fairly well known and popular one, I would assume.

Still, that doesn’t mean I fully trust all the details. For instance, were they really all siblings, sons of Homuda Wake? Or were they simply separate claimants to the throne? Even if they were all three sons of Homuda Wake, did they all have an equal claim to the throne? We’ve typically seen in the past that there is a single queen whose progeny are then eligible, but here we have three different potential sovereigns from three different queens. It is, of course, possible that the blood ties were fabricated, later, based on an assumption that it was needed to succeed the previous ruler.

Then there is the question of whether or not things were really this cut and dried. It seems like a lot, even when dressed in peasant garb, to assume that Oho Yamamori would not recognize his own brother. Things still have a somewhat fantastical bent to them, though it certainly is possible—the idea of lining the river with your men and having them shoot at someone so they could not swim to either bank seems like a tactic that someone might try.

Even if we take the whole thing at face value, though, it says something about just how perilous and chaotic the period after a sovereign’s death could be. Without a clear tradition that laid out who would succeed, fights could easily erupt between different claimants to the throne, even when a Crown Prince had clearly been named. In this case the eldest clearly thought that they deserved the throne, and the middle and youngest brothers continued to bicker over just who should have it. And while I wonder if some of that isn’t just a romantic face to a much more complex and, perhaps, bloody affair, it is probably the case that this was often what happened. Heck, even back in the stories about Queen Himiko it sounds as if there was often some chaos a ruler passed away as they tried to determine who would be next. So let’s keep that in mind as we see stories of seemingly “simple” succession stories.

I’ll end this episode with one more note, and that is actually about a rather famous shrine that is connected with this whole episode, and that is Ujigami Jinja, in, as you may have guessed by the name, Uji city.

Uji city, situated between Kyoto and Nara, is known for many things, tea being one of the more well known. Uji-cha has a long history, but not as long as what we are looking for. Uji is also home to the Byodoin, an ancient Heian aristocrat’s home along the Uji river that was turned into a Buddhist worship hall after his death. And just across the river from the Byoudouin is the relatively unassuming Ujigami Shrine.

If you didn’t already know about it, you might easily pass by this UNESCO world heritage site, and yet it features some of the oldest shrine architecture in Japan. Specifically it has a honden, or main shrine, that dates back to the late Heian period, demonstrating some interesting features of classic Heian architecture. Inside the building there are three bays, each one a shrine to the three main kami of Ujigami shrine, those being, chiefly: Homuda Wake no Mikoto and two of his sons: Uji no Waki Iratsuko and Oho Sazaki no Mikoto. Homuda Wake, aka Oujin Tennou, is considered the chief deity, and worshipped at the central shrine in the main building. Interestingly, this shrine, though worshipping Oujin Tennou, does not appear to be a part of the Hachiman cult—it is not considered a Hachiman-gu. Remember, we discussed last episode how Oujin Tennou became associated with Hachiman in later years, and this may have been an association that predates that connection. In the two side shrines, Uji no Waki Iratsuko is enshrined to the left while Oho Sazaki no Mikoto, is enshrined to the right. And while the main building is the oldest and goes back to the late Heian period, there are several other buildings on the shrine grounds that go back to the Kamakura period.

Now we aren’t exactly sure when the shrine was founded, except that it was before even the main shrine hall, or honden, was erected. The shrine is mentioned in the 10th century Engi Shiki—a collection of volumes on various ceremonies written down in the Engi era, including mention of many of the more important shrines that were part of the court system around the country at that time. It is said to have been mentioned in the Fudoki as well. That still puts it some 3 centuries after the events the Chronicles describe, but it would not be surprising to learn that a shrine had been built some time ago to a local elite, and that it is quite possible that the story that was passed down in the area would be connected with the shrine. We just don’t have any written records to confirm that this is the case.

But nonetheless, if you are in Uji, drop by and maybe pay your respects to the Prince who refused to be King.

And that’s all for this episode, until next time, thank you for all of your support. If you like what we are doing, tell your friends and feel free to rate us on iTunes, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. If you feel the need to do more, and want to help us keep this going, we have information about how you can donate through our KoFi site, kofi.com/sengokudaimyo, or find the link over at our main website, SengokuDaimyo.com/Podcast, where we will have some more discussion on topics from this episode.

And as I mentioned at the top of the episode, we are opening up recurring monthly payments and the option to become a “member”, but we are still looking at what that might entail, to include transcripts, early release, special episodes, and more. If you have ideas of what you think membership might entail, hit us up at Feel free to Tweet at us at @SengokuPodcast, or reach out to our Sengoku Daimyo Facebook page. You can also email us at the.sengoku.daimyo@gmail.com. We would love to hear from you and your ideas.

And that’s all for now. Thank you again, and I’ll see you next episode on Sengoku Daimyo’s Chronicles of Japan.

References

Ō, Yasumaro, & Heldt, G. (2014). The Kojiki: An account of ancient matters. ISBN978-0-231-16389-7

Kim, P., & Shultz, E. J. (2013). The 'Silla annals' of the 'Samguk Sagi'. Gyeonggi-do: Academy of Korean Studies Press.

Kishimoto, Naofumi (2013). Dual Kingship in the Kofun Period as Seen from the Keyhole Tombs. UrbanScope: e-Journal of the Urban-Culture Research Center, OCU. http://urbanscope.lit.osaka-cu.ac.jp/journal/pdf/vol004/01-kishimoto.pdf

Bentley, John. (2006). The Authenticity of Sendai Kuji Hongi: a New Examination of Texts, with a Translation and Commentary. ISBN-90-04-152253

Best, J. (2006). A History of the Early Korean Kingdom of Paekche, together with an annotated translation of The Paekche Annals of the Samguk sagi. Cambridge (Massachusetts); London: Harvard University Asia Center. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1tg5q8p

Shultz, E. (2004). An Introduction to the "Samguk Sagi". Korean Studies, 28, 1-13. Retrieved April 11, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23720180

Chamberlain, B. H. (1981). The Kojiki: Records of ancient matters. Rutland, Vt: C.E. Tuttle Co. ISBN4-8053-0794-3

Aston, W. G. (1972). Nihongi, chronicles of Japan from the earliest times to A.D. 697. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN0-80480984-4

Philippi, D. L. (1968). Kojiki. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN4-13-087004-1

![Takechi no [Sukune] no Ōmi on a Japanese 1 yen note from 1916.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d1a2aa7e7ccfd0001a4f03d/1627739155754-OJSEOWQ7CJ3BU0PC2KHP/Revised_1_Yen_Bank_of_Japan_Silver_convertible_-_front.jpg)